Imaginative fiction offers invaluable insights into everything from national characters to institutional malaise and pathological violence. The musings of psychologists, philosophers and historians often appear clumsy and verbose beside the epiphanies that flow from the creative hand. Thus, the visions of long dead novelists continue to colour our understanding of who we are, and where we’re heading.

We can draw a distinction between imaginative fiction and the fantasy genre. The latter according to Iain McGilchrist ‘merely recombines what we are already familiar with in a new way,’[i] (p.340) whereas works of imagination bring new experiences into being. ‘A defining quality of the artistic process’ he argues ‘is its implacable opposition to the inauthentic.’[ii]

Authenticity should be distinguished from realism. Mythology and indeed allegory – as in the The Lord of the Rings – are distinct from fantasy. A myth is not a lie, as many, including our Taoiseach, seem to assume. Rather, as Northrop Frye put it: ‘It is obvious that the world we want to live in is mythological. That is, the world we construct is built to the model of a common social vision produced by the imagination.’[iii]

Besides a lack of authenticity, fantasy does not reveal a common social vision. Usually, it aims at entertainment – a gripping thriller for example – often featuring cardboard cut-out characters representing a particular virtue or vice. At worst, we find simplistic manifestations of good and evil in a synthetic world.

This review explores whether Paul Lynch’s Booker Prize-winning novel, Prophet Song (One World, London, 2023) belongs to the genre of fantasy. My motivation is to assess the artistic value of a recipient of a prestigious prize, and further examine why such an accolade might have been bestowed.

Successively Increasing Violence

The novel charts the struggles of a middle-class Irish family – seen mostly through the eyes of the mother Eilish – living under a far-right, fascist and, according to the headline writer in the Irish Times, totalitarian regime inhabiting what is recognisably Dublin. Here, constitutional rights no longer apply, and a malevolent Garda Síochana are imprisoning, without trial, opponents of a government we learn little about.

Members of the family are subjected to successively increasing levels of violence perpetrated by agents of the state, beginning with the arrest of the father of the house Larry, a mild-mannered trade unionist. It is certainly not fantastical to assume that a trade unionist would be targeted by a fascist regime. During the 1930s many were imprisoned and sent to Concentration Camps in Nazi Germany, but especially under Mussolini in Italy ‘many even held key posts.’

A more subtle, and perhaps credible, account could have explored how a fascist regime co-opts individuals in positions such as that occupied by Larry – or even Eilish, a scientist working for a bio-tech firm. Larry does not appear to hold particularly radical views. He comes from the same background as an interrogating Garda, who he claims to have played GAA against while in UCD (p.9). Foregrounding the character of a trade unionist seems like a device allowing the author to proceed with his gory account.

Thus, we find police with batons ‘beating the marchers into grovelling shapes’ (p.30); ‘talk of internment camps in the Curragh (p.36); journalists being imprisoned (p.36); government control of the judiciary (p.58); and unmarked cars pulling up silently to lift people off the street (p.76).

What is seriously lacking in the novel, however, is any attempt to portray the insidious soft power of a fascist regime, which historically appealed to a bourgeois desire for stability and prosperity. Subtle forms of this were evident under Salazar in Portugal, who demanded that literary works observe ‘certain limitations,’ and embrace guidelines defined by the New State’s ‘moral and patriotic principle.’

Further, Nazi Germany’s Minister of Propaganda Josef Goebbels saw maintaining a feel-good factor as the essential role of propaganda. He did not want even der Fuhrer to appear in cinema news reels, believing that a subservient people should not be over-exposed to politics. Although conditions did worsen dramatically in Nazi Germany after the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, throughout much of their rule the Nazis maintained high living standards, only inflicting extreme cruelty on minorities and ideological opponents among the German people.

In contrast, Prophet Song portrays a cascade of violence carried out by agents of the state in public spaces, alongside a rapidly failing economy, where food commodities run scarce. This culminates in what seems to be the wanton murder of the adolescent child Bailey: ‘The skin before her clouded with bruising, the missing and broken teeth… nails torn from his hands and feet … a drill through the front of his knee… the cigarette burns along the torso’ (p.272). The purpose of this horrifying sequence is unclear. Perhaps it reflects the author’s dark broodings on the latent malevolence of the human condition. Later, revealingly, we are informed that insurgents are ‘just as bad as the regime. (p.206)’

True believers, such as Mrs Stamp (the wife of the nominatively determined Garda Stamp), are colourless stooges, while Eilish’s new boss, the Teutonic-sounding Paul Feisner speaks ‘not the company speak but the cant of the party, about an age of change and reformation, an evolution of the national spirit, of dominion leading into expansion.’ (p.71) These are formulaic utterances, anachronistically recalling the 1930s. However, we find none of the magnetic charisma we might expect in a fascist leader, or the stored-up resentment and scapegoating that fuel their rise.

At best, we have Larry telling Eilish that ‘the NAP is trying to change what you and I call reality, they want to muddy it like water, if you say one thing is another thing and say it enough times, then it must be so (p.20). But we can only wonder why anyone would accept such lies. There is no evidence of the infectious cynicism that Hannah Arendt observes in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951):

The totalitarian mass leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that, under such conditions, one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism; instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their tactical cleverness.

Ignorant Savages

Supporters of the regime are portrayed as ignorant savages: ‘tattoos emblazoning arms and throat … the man bringing down a bat upon the windscreen … [he]takes out his sex and urinates on the car, the apish laughing teeth as the man zips up and jumps down the gravel (p.139); who are barely literate: ‘the word TRAITER sprayed again and again in red paint.’

Thus, we find support for the regime emanating from unfortunate people at the bottom of the social ladder: ‘Two civilians are helping to build the checkpoint and she knows one of them, an odd-jobs man from the flats nearby, an ex-junkie with hardly a tooth in his mouth.’ (p.187)

There are suggestions that those in power are targeting minorities – such as when we learn that a certain Rohit Singh has been arrested – but no account is offered from the perspective of any minority group. A novel should not be an exercise in empowerment, but the prevailing cultural homogeneity in Prophet Song hardly diminishes the deadness of this account.

There are also apparent endorsements of an Irish economic model that produces galloping growth rates amidst a housing crisis and rampant homelessness. A sign, therefore, of the country’s decline in the novel is where ‘every day another international firm closes its doors and makes its excuses’. (p.124) We must assume the presence of multinational corporations in Ireland is ipso facto a good thing, rather than underlying the development of a two-tier society, now generating serious social cleavages.

There are nods to contemporary concerns, such as when Larry points to the ceiling and warns his wife to keep her voice down (p.5), but the characters rarely appear concerned about creeping surveillance, as violence is largely inflicted in random fashion.

Raqqa, Syria.

Depicting Another Country?

Prophet Song is a novel that seems better suited to the depiction of a post-colonial country, where a distinct ethnic or religious group has assumed control over the levers of power and monopolises violence in a divided society. It might have been written about Syria, where army and state have long been dominated by a distinct religious group.

It provides no insight into the insidious means by which a fascist government could take power in Ireland. The regime is a resident evil inflicting at times wanton suffering. Any such government would surely only appeal to the most base or desperate. This may reflect the author’s assessment of the human condition, but even if we accept there is a murderer in us all, it is surely incumbent on a fictional account to demonstrate how any diabolic metamorphosis occurs. Here the main characters are simply victims. In the absence of authenticity or a common social vision it should be consigned to the fantasy genre.

I do wonder why the novel has received critical acclaim, and the accolade of a Booker Prize? Aside from a general neoliberal degeneracy now infecting most cultural organisations that place a higher premium on sales potential than artistic expression, the best explanation I can think of is that it reflects, and arguably exploits, the anxieties of the British cultural establishment in the wake of Brexit and Trump, making it ‘crucial reading’ according to the The Guardian.

Essentially, it is a politically correct thriller ungrounded in political reality. Contrary to the feverish headlines, the November Dublin riot can be traced to decades of government neglect of the inner city; sporadic attacks on refugee housing do not reveal a broad-based political movement on the brink of power in Ireland. Perhaps the panel of Booker judges are oblivious to how – unlike many European countries – Ireland has not seen an upsurge in support for far-right parties. Even to suggest that we face the prospect of fascist, totalitarian governments across Europe stretches credulity.

With shifts in technology, contemporary forms of totalitarianism may be very different to what we have witnessed in the past, which is not to dismiss the relevance of dystopian prophecies such as Alduous Huxley’s Brave New World (1931) and George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) and 1984 (1949). Sadly, Prophet Song offers no such timeless lessons.

Why does any of this matter? In an interview in 1994 Harold Bloom argued that what he described as a school of resentment had destroyed the art of reading, marginalising three thousand years of imaginative literature. He added ominously that if shallow authors are promoted for political reasons you will not augment memory or cause the mind to grow and that ultimately this would impoverish our imaginations.

[i] Iain McGilchrist, The Master and his Emissary (Yale, 2009), p.341

[ii] Ibid, p.374

[iii] Northrop Frye, Spiritus Mundi – Essays on Literary, Myth and Society, (Indiana University Press, 1976), p.89

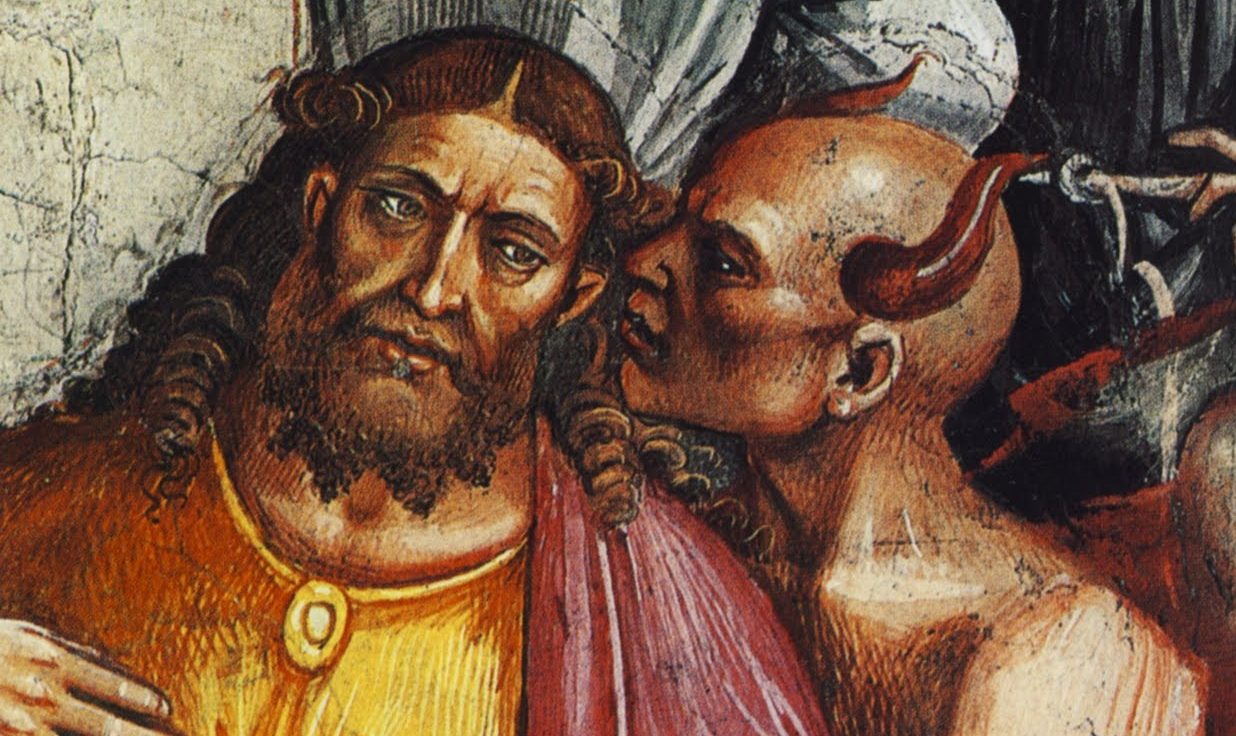

Feature Image: The Devil whispers to the Antichrist; detail from Sermons and Deeds of the Antichrist, Luca Signorelli, 1501, Orvieto Cathedral.