In his first article Dan Mc Auley revealed some of the hidden secrets below Dublin Bay, and a looming threat to that environment. In this article Dan takes us to the mysterious world of shipwrecks around the Irish coastline, of which there are a remarkable 18,000, two of which he has been taking photographs of for nearly twenty years.

When divers receive their initial certification as Open Water Divers under the PADI training system the next step is the Advanced Diver Programme. This teaches the many different disciplines available in the diving world, including Drift Diving, Photography Diving, Drysuit Diving and Night Diving. There are, therefore, many options available to the newly certified aquanaut, but without doubt the most popular and sought after certification is in Wreck Diving. Wreck Diving offers a snapshot of history on the ocean floor.

With the combination of a long history of maritime traffic and often quite ferocious seas, it comes as no surprise that the Irish coastline is strewn with shipwrecks, many of which date back hundreds of years. Each one provides a fascinating porthole on a bygone age, telling stories that are often of historical significance, as well as allowing divers a chance to encounter what are often quite intriguing new environments for marine life.

Shipwrecks are formed when human ingenuity is defeated by the raw force of nature, and often tell a tragic tale.

Julia T.

18,000 Shipwrecks

According to the Underwater Archaeology Unit (UAU), there are over 18,000 shipwrecks along the Irish coastline, which is more than enough to keep even the most gun-ho of ‘wreckies’ (wreck divers) satisfied for a lifetime.

Obviously not all of these are diveable, or even worth exploring, as their journeys don’t end when they reach the sea bed: the relentless ocean keeps working on these vessels.

Sometimes in shallow waters they can be quickly broken up into smaller and smaller pieces as waves pummel the steel or wood of the ship against the sea bed. If a ship runs aground in deeper water, however, a slower process begins, as nature slowly reclaims the ship: firstly by turning it into a reef that becomes a refuge to marine life clear of the sea bed.

This offers a treasure trove of subjects for an underwater photographer, concentrated in an area easily dive-able on one tank.

As the process of disintegration continues apace, cargoes are often shifted across the sea bed. The story continues with different species of marine life taking up residence in the hulls of the ship, just as sailors had enjoyed that privilege above the surface.

Hook Head Wreck.

First a Confession

With such an array of shipwrecks around the coastline to choose from, it is tough to decide which stories to tell in a single article; I will therefore focus on my two favourites, and explain what makes this pair special to me.

Before doing so I must confess that I am by no means a true ‘wreckie.’ Rather, I relish the opportunity to photograph the marine life these wrecks attract. This natural profusion is my true love, as opposed to the history of the wrecks themselves.

A true wreckie would probably want to hear about the Cunard ocean liner RMS Lusitania that was sunk by a German U-Boat in 1915, eighteen kilometres off the Old Head of Kinsale, killing 1,198 and leaving 761 survivors. This appalling loss of life was among the reasons why the United States eventually joined the Allied side during World War I.

Others would be drawn to SS Laurentic, another British ocean liner of the White Star Line that was converted into an armed merchant cruiser at the beginning of World War I. That vessel sank after striking two mines near the Inishowen penninsula north of Ireland on January 25th 1917, with the loss of 354 lives. She was carrying about 43 tons of gold ingots at the time, and, intriguingly, twenty bars of gold are yet to be recovered.

Instead the wrecks I have chosen are two that I have dived nearly every year for the past twenty years, and have had a chance to watch at intervals their continued journeys below the waves.

Julia T.

Julia T

The wreck of the Julia T is located in a top secret location off the variegated Mayo coastline, known only to initiates to one of Ireland’s top dive centres, Scuba Dive West.

A shroud of mystery continues to lie over what brought it to the sea bed. This perhaps emanates from a curious indifference on the part of the Irish state to the value that wrecks offer to divers when these become man-made reefs on the sea bed.

As a result, nobody knows precisely what caused this ferry to sink to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean in an ideal location at exactly the right depth and area for divers to explore. What we do know is that the ship sank without any spillages or casualties and without causing any environmental damage on July 4th, 1998, while under tow to be decommissioned after a lifetime supplying the Islands communities of Inish Boffin and Inish Turk off the Galway coastline.

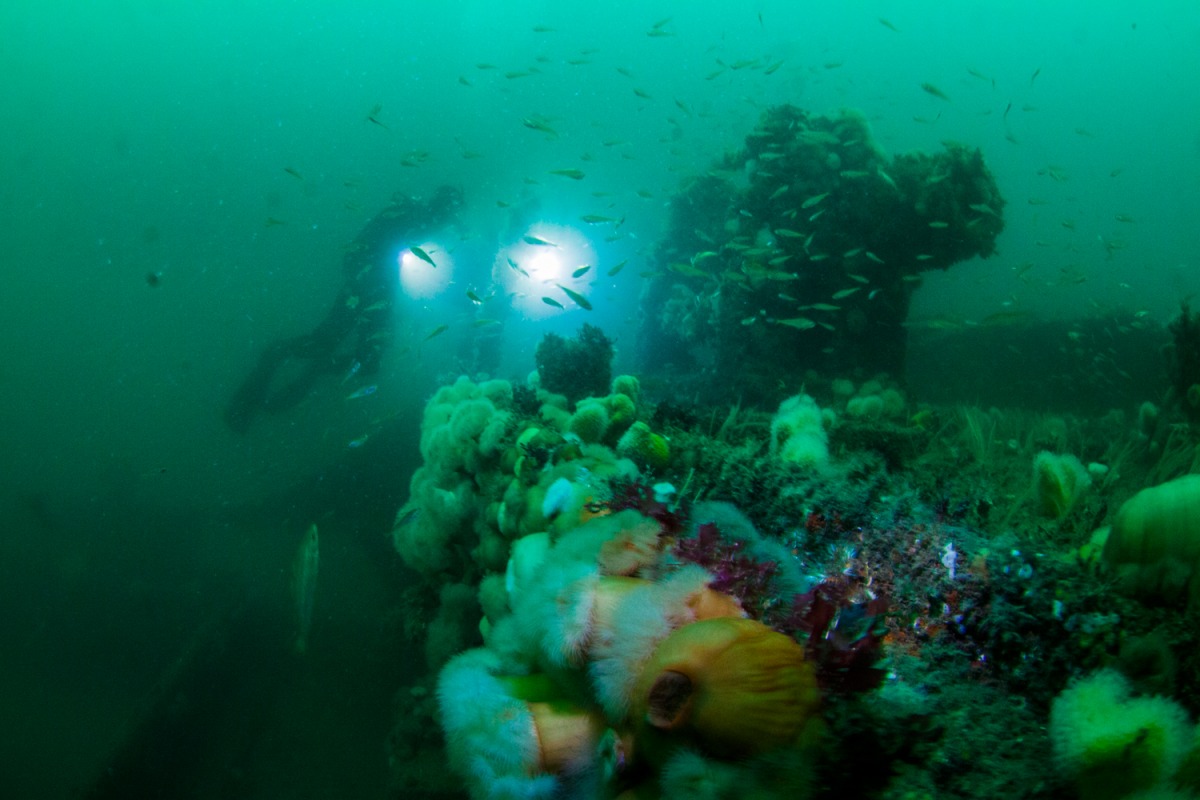

Julia T.

At over thirty meters in length it was the last in the line of the Clyde-built boats (so-called Clyde Puffers) with a flat bottom to allow for beach landings, which now allows it to sit perfectly upright on the sea bed.

I have been lucky enough to dive it nearly every year since it first sank over twenty years ago, with each dive offering fresh insights into what happens to a ship once it descends below the waves.

Situated at an ideal depth for advanced divers of twenty metres, it has provided a perfect training ground for imparting the skills essential for safely exploring wrecks; whetting the appetite of many a newly blooded wreckie to explore other sites along the coast.

Julia T.

A Profusion of Life

Since sinking to the sea floor it has become a safe home for thousands of marine critters, amidst the might of the Atlantic Ocean. In excess of forty exquisite nudibranch, a soft-bodied, marine gastropod mollusc, have been recorded on the wreck on a single dive. Nudibranch appreciation clubs now travel annually to the site of the wreckage to spot these elusive and colourful creatures.

Shoals of mackerel and cod also often take refuge from the raging seas in the large hull of the ship, while varied species of brightly coloured wrasse fish use the wreck as a nursery for their young, before heading out to deeper water.

The mighty conger eel has also been spotted lurking in the darker parts of the wreck, along with passing thornback rays on the sea bed around the wreck.

Over the years more and more filter feeders, like the plumose anenome have carved out a niche in the wreck, as well as the awe-inspiring jewel anenomes that bring a vivid colour to the rust-coloured exterior of the wreck.

Given the extent of this cornucopia of marine life it is hard to see just where the man-made structure ends and nature now begins. Indeed, the monetary value of the material constituents of the wreck is now a tiny fraction of its value as a dive location, and for marine life. The site now draws hundreds of international divers, and is regularly listed as one of the top dive destinations in the world.

Julia T.

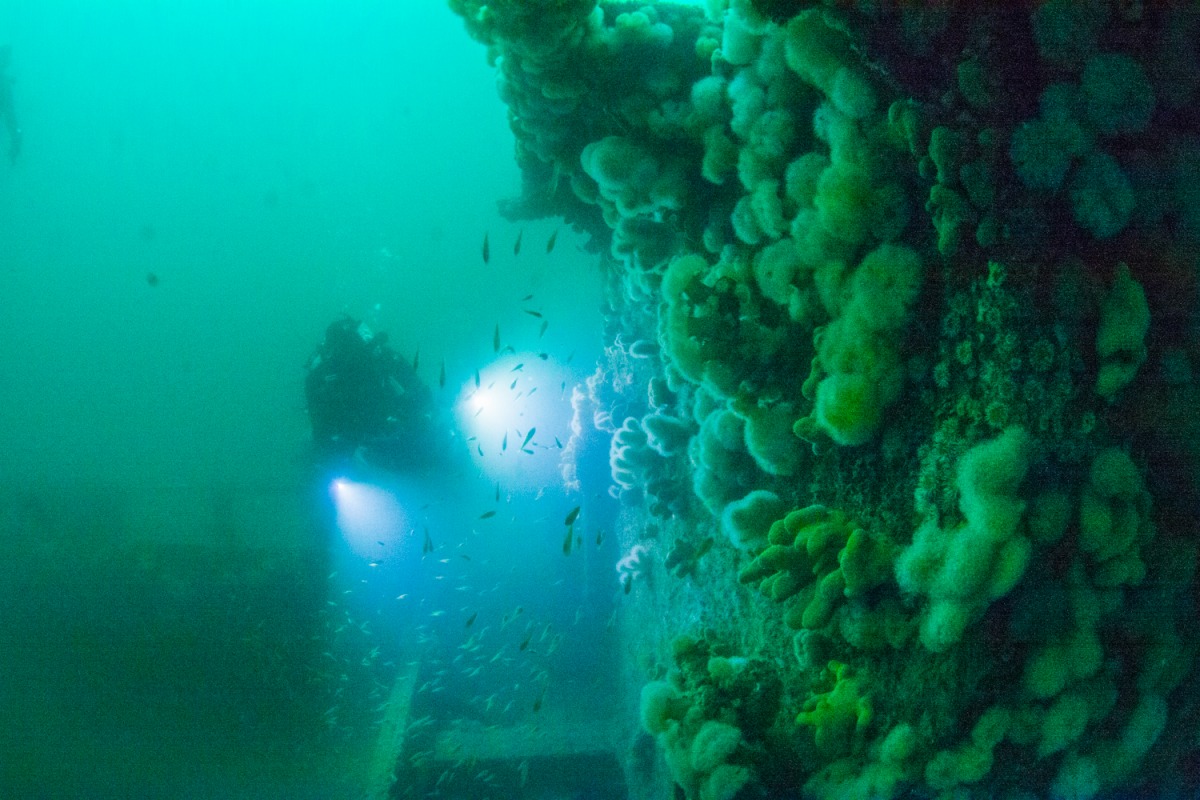

Unnamed Trawler

The second wreck I visit each year is located in much shallower water, barely eight meters below the surface by the beautiful Hook Penninsula in county Wexford. Very little is know about the first incarnation of this unnamaed trawler that sank in the 1960s, as is often the case with ships before they meet the ocean floor.

This shipwreck lies in the surge zone – constantly pounded by the southerly swells that carved the Hook peninsula itself – meaning its ageing process is starkly different to that of the Julia T.

On my annual descents I have observed just how rapidly nature is able to reclaim what is left by man. The metallic shell of the wreck is regularly hit with such concussive force that the base elements have actually melded into the stone shoreline, with only the strongest parts now recognisably part of a ship.

At this stage the engine block sits proudly on the seabed, with the propeller and its drive shaft streaming out of it, giving the impression of a skeleton of a prehistoric sea creature.

The engine block is an occasional home to spider crabs that come to shallower waters every year to mate before returning to the deep sea.

Each year offers new insight into the ferocity of the winter storms, demonstrating how the incredible caves and blowholes have been carved over millennia into the unique Hook peninsula.

This dive, although accessible from the shore, requires divers to go by foot for half-a-kilometre in full scuba gear before taking the plunge. It’s certainly an endurance test, but at least the coastline is a feast for human eyes.

Hook Head wreck.

Mapping Underwater

Over the last few years a project has been completed by the team at Infomar to map the entire under water sea bed in Irish territorial waters, an area which is over ten times the size of our land-based territory.

This incredible feat harnessed the most recent technological advances, and is an achievement that few other countries can lay claim to. It offers remarkable insights into the wealth of marine life along our coastline, which will hopefully be preserved for future generations to encounter.

All of this data is easily accessible via Infomar’s website, and anyone with an interest in the secrets below our seas should take a look. So far they have released 3D imagery and articles on 65 of the 18,000 shipwrecks.

In terms of other resources, there is also a wealth of knowledge contained in the National Maritime Museum of Ireland in Dun Laoghaire, with recovered artefacts on display from what are often tragic shipwrecks. For just a few euros aspiring wreckies can learn about the history of the wrecks they intend to visit.

Important Insights

As an underwater photographer shipwrecks will always hold a fascination. Perhaps the most important insight I have drawn from my many visits to these manmade reefs is how quickly nature reclaims the structures that we discard, rapidly transforming our waste into natural capital. Once barren sea beds can even be transformed into incredible ecosystems by what may initially seem to be the intrusion of an alien vessel, practically overnight.

As we struggle to feed the many billions of human beings on our planet sustainably, it is perhaps worth considering the speed at which the sea converts our waste ships into nurseries for marine life. This process demonstrates how little we really understand about life below the ocean’s surface.