Jacques Cousteau, the inventor of the aqua-lung which finally allowed human beings to roam freely under water once said: ‘The sea, once it casts its spell, holds one in its net of wonder forever.’

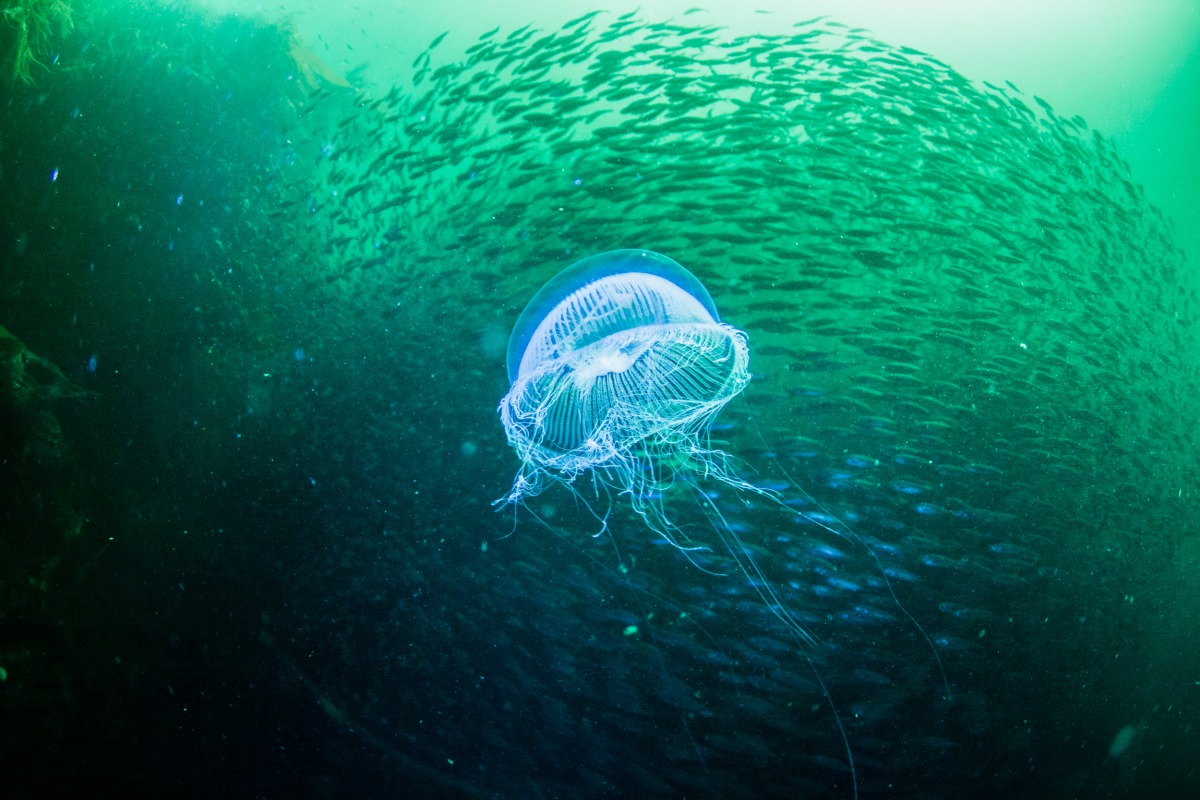

Like many other kids growing up in Dublin, I first learned to swim in the two-hundred-year old man-made harbour of Sandycove. Gifted a birthday present of a rubber diving mask by an adventurous uncle I was immediately mesmerised by an incredible world that didn’t follow the predictable conventions of dry land, with shimmering shoals of white bait and sand eels darting among the stunningly beautiful kelp forests that surround Sandycove.

Like Jacques Cousteau, the sea had caught me in its net and my early love of underwater Dublin Bay led me to become first a snorkeler and then a scuba diver. I qualified as a scuba-diving instructor in 1998, and since then I have been working with the fantastic team in Oceandivers, who have had the pleasure of introducing thousands of divers to the incredible underwater world on our doorstep in Dublin Bay.

Hook Head Wexford.

Underwater Photography

I took up underwater photography soon after becoming a dive instructor. Since then I have been bringing a camera along with me on dives as much as possible. I began shooting on 35mm film with an amphibious camera, and have kept up as much as possible with the fast moving technology over the past twenty years.

Bringing electrical equipment into salt water is never a smart idea, let alone cameras that cost thousands of euros! I have had more than a few teary endings to dives as water snuck past a vital rubber barrier.

Saint John’s Point Donegal.

I have spent hundreds of hours photographing some of the country’s most dramatic landscapes, hidden away from most of the population, and am constantly on the look out for new audiences for the beautiful underwater scenes I am lucky enough to capture.

Being underwater is not something our body can endure for long without the assistance of technology, primarily the aqualung that Cousteau invented in the 1940’s, which heralded the arrival of the underwater sport of scuba diving. With over ten thousand certified scuba divers now in Ireland, we have a substantial number of active amateurs and professionals diving regularly all year round, all along our incredible 5,500 km of coastline.

Divers on Dublin Bay.

These divers are rewarded for braving our cooler waters with incredible scenes of raw nature, and dramatic underwater scenery that rivals any of the best dive locations in the world.

Cousteau himself rated some of the sites he dived in Ireland as being among the best in the world. The west coast in particular offers a multitude of islands and sea cliffs in deep clear Atlantic water, interspersed with the wrecks of unfortunate vessels that ran aground in the oft wild conditions. To explore every dive site on the west coast would take a lifetime, with new sites being discovered every season by intrepid divers.

Horn Head Donegal.

Dublin Bay

Due to the density of population in our capital city, Dublin Bay is one of the most well-dived locations in the country, despite at times having less than ideal diving conditions.

Divers trade in ‘Viz’ or underwater visibility. As a rule, the clearer the water the better the dive. Divers depart from Dun Laoghaire Harbour to the south and Howth harbour in the north, finding adventures around Dalkey Island or Lambay Island; or surveying shipwrecks off the Old Bailey Lighthouse or on the Kish sandbank.

The silt and sandy bottom around Dublin Bay is in a state of constant motion, drawn by the strong tidal flows moving down the east coast of the country. These massive sand banks are also easily disturbed by strong southerly or easterly winds, leading to dramatic drops in visibility when a strong wind blows. Unlike the deep water off the west coast, Dublin Bay is a relatively shallow body of water with a primarily sandy bottom.

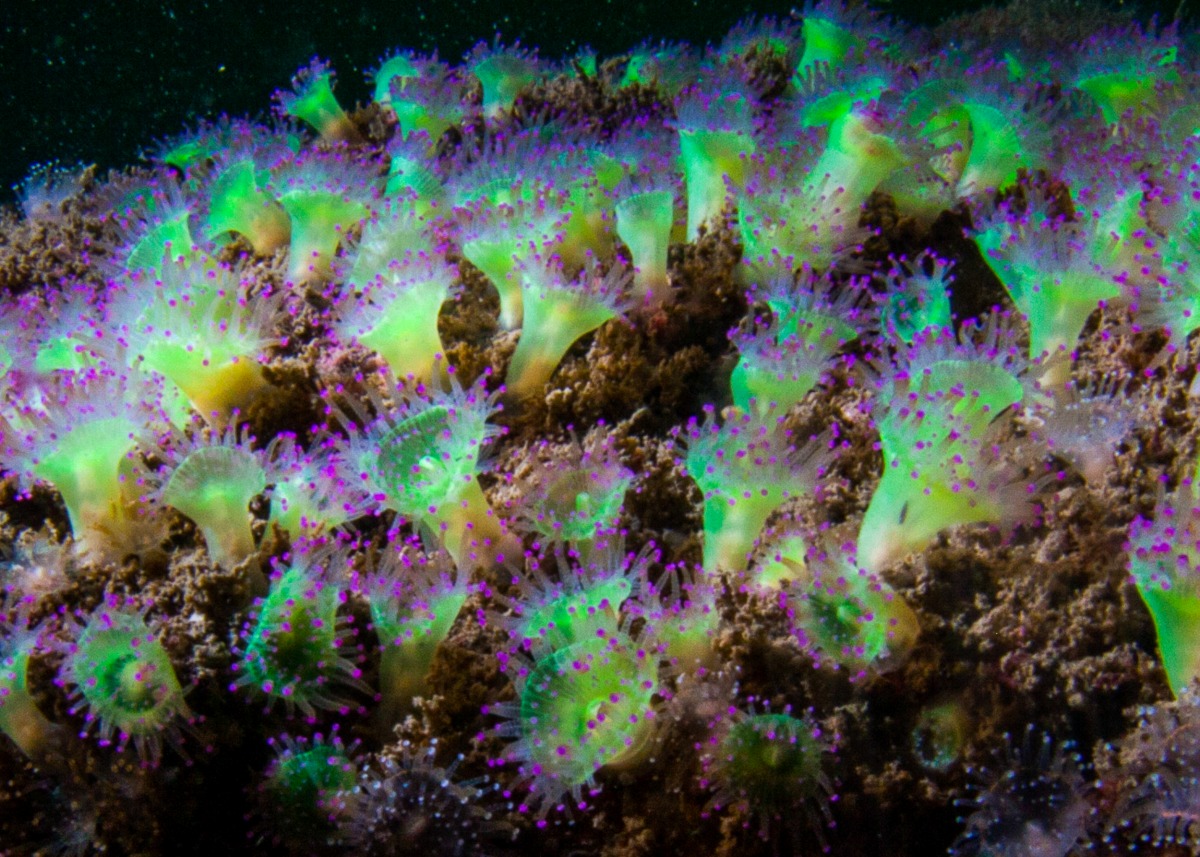

Coral Garden Dalkey Island, Dublin Bay.

The sediment and sand along the northern half of the Bay is particularly plentiful, meaning the dive sites there are extremely poor, with visibility rarely rising above a metre or two. But on the southern side of the Bay there are sites where visibility regularly reaches beyond five metres, providing reasonable conditions for divers to train in.

Hook Head, Wexford

Sandycove is among the few locations in the Bay where divers can regularly access clear water with the depths required to train new divers in safe conditions.

Recently, under the guise of Covid-19 prevention measures, divers were denied vehicular access to the site as a result of a poorly designed bike track. This removes one of the last accessible dive sites within the city, and hopefully a solution can be found.

Dalkey Island, Dublin Bay.

Dalkey Island

The rocky outpost of Dalkey Island, jutting proudly out of the sandy sea bed, offers the best of the boat dive sites in Dublin Bay, with an incredible ecosystem flourishing just a stone’s throw from the capital.

Watched over by a thriving seal colony along the surrounding coastline, Dalkey Island offers a thriving marine environment, which is fed by rushing tidal flows as the waters empty from Dublin Bay and are funnelled through the two sounds between the island and the mainland.

This incredible wilderness is close to the heart of the city, but alas so few take the opportunity to visit it either above water or below. Yet DART services run every few minutes from the centre of the city out to Dalkey (a less than 30 minute ride), from where a ferry leaves for the unspoilt Island.

The Bills Rocks off Galway.

Dead Zones

As indicated, a few natural factors deny Dublin Bay the crystal clear water that divers can find along most of the west coast. This sand and silt in Dublin Bay is easily stirred up by wind so visibility can drop from ten meters to under a meter in the space of a few hours. Moreover, as you move along the coast from the north to south numerous large rivers carry silt into the low depths of the Irish Sea, with the same process occurring along the Welsh coastline; the distance between Dublin and the island of Anglesey, where the port of Holyhead is located is barely a hundred kilometres.

Killary Fjord, Galway.

Looking to the future for Dublin Bay, the biggest concern is that what has happened in the Baltic Sea will be replicated on the Irish Sea, including Dublin Bay.

Dead zones form when an excessive level of nutrients, primarily nitrogen and phosphorus, enter coastal waters and fertilize algal blooms. When these algae die and float to the bottom, they provide a rich energy source for bacteria, which in the act of decomposition absorb oxygen from surrounding waters.

The Irish Sea has already numerous dead zones recorded around river estuaries, especially from the large rivers in the south east. The worry now is that these will expand and overwhelm more of the Irish Sea’s thriving wildlife.

Over the last forty years the Baltic Sea has transitioned into a near holistic dead zone, as divers watched on in horror, and the relevant authorities in different countries failed to act.

Killary Fjord, Galway.

A similar fate is not inconceivable for the Irish Sea, if sufficient care is not taken of this precious resource. Although we have the advantage over the Baltic Sea of an opening onto the wild Atlantic on either end – allowing a flushing effect from the tide – what we do above ground will ultimately makes its way into the Irish Sea

- Hook Head, Wexford.

- Coral Garden, Dalkey Island, Dublin Bay.

- Horn Head, Donegal.

Decisions made by our farming, construction and logging industries, along with our waste water handling, will decide whether we preserve this unique ecosystem – the last remaining great stretch of wilderness on our doorstep.

Conservation will also requires the same level of commitment from our near neighbour across the water, as we share a guardianship of this body of water, and the decisions we make in Ireland will be insufficient.

All Photographs are taken by Daniel Mc Auley from Dublin Bay, Donegal and Co Clare.