In October 2018, I wrote an article for the Irish Medical Times entitled: ‘Acid Test-are hallucinogens finally shaking off their taboo?’ The impetus came from reading Michael Pollan’s How to Change your Mind (New York, 2018), Michael A.Lee’s Acid Dreams The Complete Social History of LSD: the CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond (New York, 1985) and James Fadiman’s The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide (Maine, 2011), all of which explore the history, myths and indisputable facts around what has been, over many decades, a highly contentious subject.

I was surprised that the Irish Medical Times deigned to publish it. After all, these are schedule 1 substances, i.e. ‘dangerous substances with no medical or scientific value’ according to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1977.

In hindsight, I consider my 2018 article naïve and anachronistic, leading the reader to believe that these substances are, for the most part, recent cultural adjuncts.

The Immortality Key

A recent award-winning book by Brian C. Murareska, The Immortality Key The Secret History of the Religion with No Name (New York, 2020) on the use of ‘mind-manifesting’ (psychedelics) or ‘god-inspiring’ (entheogens) and their use in human cultures for millennia prompts this revisionist take.

The book explores such practices as the use of kykeon, a plant-infused wine used during the infamous, but little understood, Eleusinian Mysteries; the Vedic traditions of India in which a similar psychedelic substance called soma was consumed; and the cultures of south and central America where ayahuasca, peyote or psilocybin are still used in their religious ceremonies.

The human desire to ‘turn on, tune in and drop out’ long predates Harvard Universities notorious Professor Timothy O’Leary, once labelled ‘America’s most dangerous man’. Although, this latter titled was supposedly bestowed on him by a President who vowed to bomb an agrarian society ‘back to the stone age’ in the name of democracy.

What can explain a near universal desire, traversing cultures and millennia, for psychedelics? And why has its practice been vilified, persecuted and legislated against, pushing it into the underworld of crime, rather than exalting and exhibiting it as a means to transcendence and spiritual enlightenment?

Drug use in the 1960s was portrayed by the media – with help from the CIA – as posing a threat to respectable society – middle class, consumerist values hypocritically portrayed as love of family, country and God. What it really represented was a genuine threat to production of drones for the corporate, industrial and military establishments.

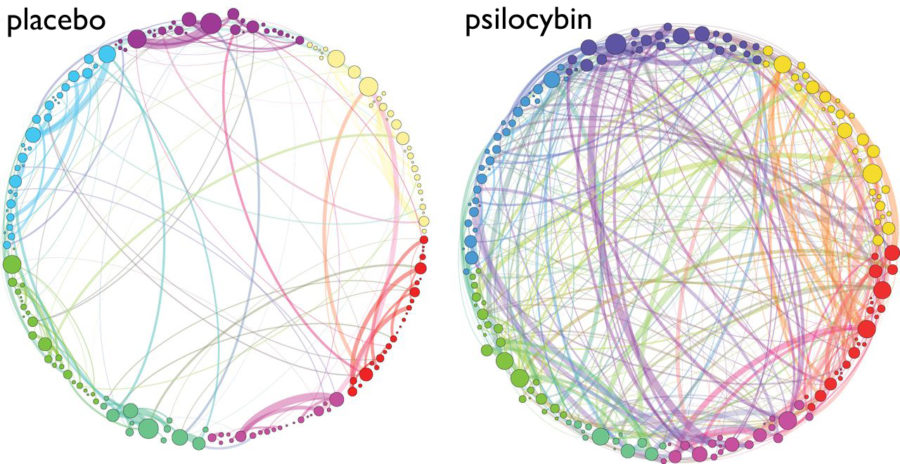

Evidence of the health benefits of these substances, if used in controlled and supervised environments, were clear, even in the 1960s. By then a thousand research papers were in print demonstrating dramatic therapeutic effects for conditions such as chronic depression, alcohol dependence and anxiety in cancer patients.

Canadian psychiatrist Humphry Osmond obtained abstinence in 45% of his alcohol dependent patients at one year post treatment. There are no products today in the field of addiction medicine that can produce such impressive results.

Then all studies were stopped, the substances were deemed dangerous and subsequently made illegal, even in research settings; this despite their non-addictive nature. In fact, repeated dosing has less and less of an effect.

Yet these are drugs with an excellent safety profile, as it is almost impossible to overdose. They have clear health benefits and provide spiritual insights. Nonetheless, for over thirty years no further research was allowed to be carried out.

Finally, in early 2000 Professor Roland Griffiths at St. John’s Hopkins University, Baltimore carried out the first of the latest wave of research using psilocybin (the active ingredient in several species of fungi, P.semilanceata, or Liberty cap mushrooms – that can be found here in Ireland).

Now Imperial College, London and even Tallaght University Hospital have carried out research using these substances.

Caveats

Before going any further in extolling the virtues of psychoactive plants from historical, cultural or medicinal standpoints it is worth highlighting serious caveats.

Psychoactive substances, and that includes alcohol, should not be used by those with immature brains, i.e. those under twenty-five years-of-age. Before this age the prefrontal cortex – that bit of the brain that makes you do the right thing when the right thing is the hard thing to do, according to Robert Sapolsky’s Behave: the Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst (New York, 2017) – is not fully developed.

Clearly, as witnessed in our world at large, this maturation process is not inevitable. Two essential conditions for the safe use of these substances are usually absent when young people ‘drop a tab’ washed down with a bottle of vodka on an all-night bender, with equally immature and vulnerable friends.

These are the set (the mindset) and the setting (an appropriately supervised environment). These substances were never meant to be abused in this way. Indeed, there are so many things in our society that were never meant to be abused – love, trust, community, friendship etc.

If we broaden out the list of psychoactives, beyond the schedule 1 substances, we do encounter substances as harmless as nutmeg, nausea-inducing fly agaric (the iconic red and white fungus of children’s storybooks), the lethal mandrake (of witch folklore) and Deadly Nightshade. Apart from shamans in Lapland drinking fly agaric laced reindeer urine, who even knows about these substances?

So why the paternalistic need to protect society? To my mind it is part of a sinister power play between the perceived powers of good, i.e. Church and State and evil i.e. the ungovernable, the anarchistic psychonaut.

This is of course a nonsense, fairytale for adult consumption. Those who have used and currently use psychadelics responsibly are looking for shortcuts to enlightenment by transcending the world of the everyday perceived consciousness, in order to experience the numinous.

Anarchy

Such aspirations are equated with anarchic ideas questioning the need for the boundaries of laws and earthly rules if one experiences transcendence.

The question may be asked: what need is there to fritter one’s life away in meaningless work to earn valueless money to spend on vacuous consumer goods if one can experience Nirvana?

And what need would there be for the religious authorities of the world, if one achieves direct access to the heavenly realm whilst still on earth, or if one can die before one dies?

These very concepts bring us to the main theme of Brian C. Muraresku’s The Immortality Key, exploring various ancient traditions, over three thousand years, in which psychedelic substances were used to achieve these transcendent states.

These were traditions and practices guided and controlled mainly by women, and they continued up until their brutal eradication by the many Inquisitions of the Catholic Church.

These psychedelic ceremonies were disruptive because of their use of drugs by women to bypass manmade barriers to transcendence. Muraresku’s research supports The Pagan Continuity Hypothesis that implies that much of Christian and indeed Western culture has borrowed more than it wants to admit from ancient ‘barbarian’ cultures.

Depiction of the Aztec goddess Itzpapalotl from the Codex Borgia.

Role of Women

The role of women as holders of sacred knowledge was systematically undermined from the eleventh to the seventeenth centuries, especially by the Papacy during the many Inquisitions, and also by the early Protestant churches. Tens of thousands of women were tortured and murdered because of male fears of their sacred, potentially subversive knowledge, and not because they were ‘witches’, wreaking havoc on innocent communities.

The Church has always feared woman. Mary Magdalen should have become the first Pope ahead of Peter, and spread the word of Jesus, which required no institutions to disseminate, and no male power to dominate.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote lucidly about the Catholic Church’s dilemma in The Brothers Karamazov. ‘The Grand Inquisitor’ a Jesuit, clearly explains to the returning Jesus why his potentially disruptive presence is unwelcome – and that his religion of personal responsibility on the path to enlightenment could negate the role of all-powerful Church.

Today our society reflects this loss of spiritual responsibility. Those practising formal religions may read the holy books but generally take them too literally, and often live lives devoid of profound contemplation.

Many of the flock consume religion like they consume capitalist goods, failing to question the meaning of the texts as they fail to explore the source of their cheap consumer goods surrounding them.

Similarly, we consume products that are allegedly food, but don’t nourish us; information from media companies that doesn’t inform us; and pharmaceutical products that promise health, but perpetuate illness. All are profiting from a sick society.

Preparation of Ayahuasca, Province of Pastaza, Ecuador.

Full Circle

What effect would widespread use of psychadelics achieve today? Perhaps a reduction in the level of fear in society; and less social atomisation as we move away from an increasingly locked-in and isolated world of gadgets and home deliveries.

It could perhaps lead to greater rejection of hierarchical authority, one often based on arbitrary rules and which offer only self-serving explanations about why society should be moulded in one way as opposed to another, more intuitive, way. Psychedelics might even lead to greater self-reliance, and a more human-centred form of socialism.

The wisdom our ancestors knew, and cherished, which, for the most part, we have arrogantly disregarded in favour of materialist theories in science, offers great insights.

Perhaps we are coming full circle, as Bernardo Kastrup discusses in his series of essays Science Ideated: the fall of matter and the contours of the next mainstream scientific worldview (New York, 2021).

Traditionally, science has mistakenly assumed mind and consciousness to be epiphenomena of materialism. However, having reached an impasse, especially in the science of consciousness, we require a revaluation, and perhaps greater humility towards the wisdom of Hinduism, Buddhism and the Sufi tradition of Islam, as we consider what these have to say about mind and consciousness.

The awakening of an interest in psychedelics, both in academia and in society at large, perhaps reflects an intuitive desire to know more than science can explain, and learn more than fundamentalist religious teachings can reveal, instead validating a felt experience at a deep spiritual level.