It’s easy to despair in the face of our species’ (homo sapiens: ‘wise man’) apparent unwillingness to recognise environmental constraints. The facts of life on planet Earth have been laid bare to most of us by now. We cannot go on consuming as many of us do in the West indefinitely, especially with populations in developing countries increasingly adopting our lifestyles.

Denial is the default, including by chipping away at the edges of an incontrovertible proposition that humans are out of balance with nature; but also in terms of how we satisfy our desires individually – sure a little more won’t do any harm. There is always some excuse or other available to avoid taking responsibility for our actions.

Pope Francis previously described a dysfunctional relationship with Mother Earth:

This sister now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will.

Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine ought to bring this serious imbalance home to us. Underlying the aggressive posturing in response – and crazed talk of no-fly zones that could precipitate nuclear war – is a hard-nosed recognition that European countries will continue to purchase oil and gas from Russia. So, how should conscientious individuals respond to the impasse?

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s statement comes to mind: ‘Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.’ In moments of crises holding back from holding forth is often appropriate.

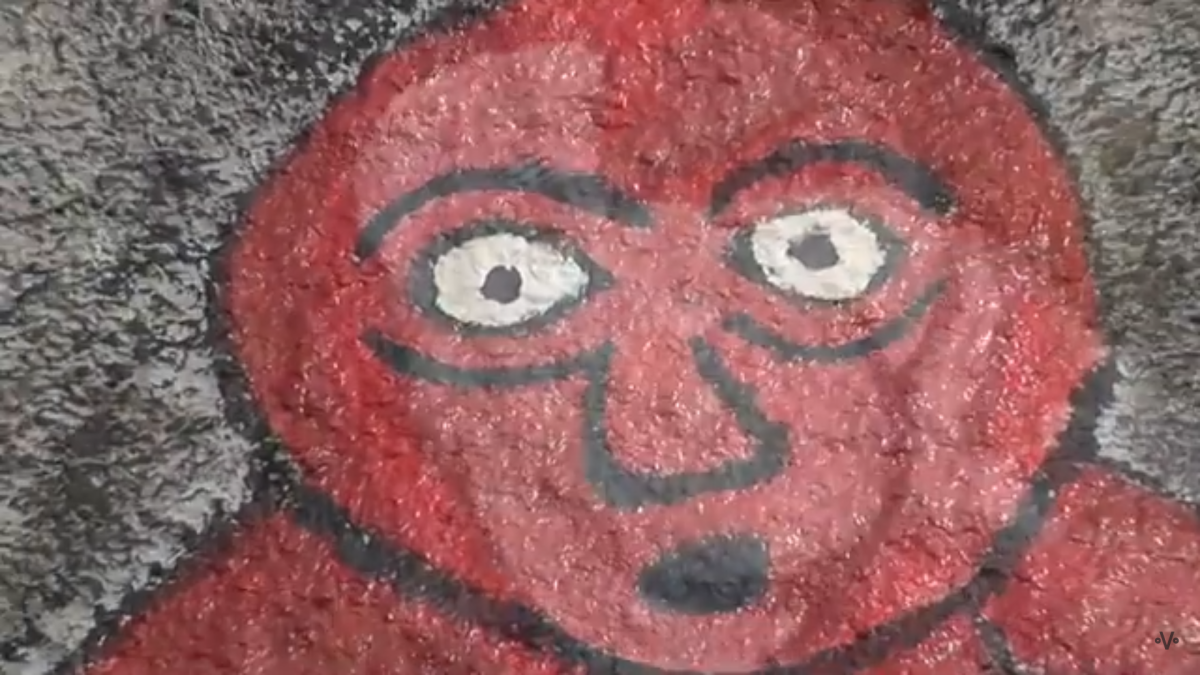

The reflection required is also facilitated by viewing Bob Quinn’s short (16 minutes, 48 seconds) film ‘Bog Graffiti’, which mostly wordlessly documents the co-existence of his art work and nature on land he has regenerated in Conemara. The unspoken context is climate change. Another of the old masters, pioneering electronic music composer Roger Doyle provides a score that artfully integrates the elements.

Art in nature in Bog Grafitti.

Bob Quinn explained the concerns animating the film in a 2019 blog post:

The desertification of the Sahara happened suddenly.

Six thousand years ago northern Africa had as temperate a climate as Europe, had two lakes as big as Munster. It was fertile enough to support a settled agricultural population and their gods. There were fauna too, antelope, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, crocodile roaming as freely as the human animals.

Over a couple of centuries – the blink of a geologist’s eye, according to a computer simulation (Milutin Milankovic Medal, 2005) – a combination of local vegetative and atmospheric changes in the area (recorded in deep land and sea cores) caused a local climate event – the Sahara event.

It should not surprise us. During another of this planet’s many interglacial warming periods , alligators thrived at the north pole; there are fossils to prove it.

A blindspot of our species is that we confuse weather with climate. Humans do not cause destructive climate events; we accelerate and intensify their frequency. Unexpected change follows unregulated ‘progress’: our cars, our holiday flights, our excessive consumption.

Present climate change is, like politics, global but people experience it in local terms: a drought in one place, a tsunami in another, forest fires here and there. Tough luck on poor people, faraway. It couldn’t happen here?

Alas, homo sapiens is all the one, seven billion of us, all on the same tiny planet, as voracious and unthinking as mice sailing on a ship of cheese.

The film puts on a display of the natural world, from bees to butterflies, in all its glory, and gore. A poignant moment is the sight of a bat writhing in agony in a pool of cooking oil. At least we are a little more aware now that the bat may yet have its revenge, over humankind at least.

A bat fails to recover its flight in ‘Bog Grafitti’.

Filmed in 2019 at a point when – prompted by a certain teenager from Sweden – many of us were facing up to the challenge of climate change, it is appropriate perhaps that the scenes in the film are seen through the eyes of a young girl – Bob Quinn’s granddaughter Sasha May Quinn. She seems destined to inherit this Garden of Eden, but as we see in the film, storms are moving in – interspersed with scenes of motor cars, cattle marts and aeroplanes demonstrating the excesses of consumption. It begs the question: what will remain for the generation to come?

Bog Graffiti is the work of a master craftsman teaching us what we know already in our hearts but generally fail to acknowledge in our conscious actions. The film ends with the Latin motto: ars longis, vita brevis ‘skilfulness takes time and life is short,’ which originates in a Greek text, Aphorismi written by the Father of Medicine, Hippocrates.

Appropriately perhaps, the lines following from that text state: ‘The physician must not only be prepared to do what is right himself, but also to make the patient, the attendants, and externals cooperate.‘ Thus, art such as Bob Quinn’s can impart a lesson, but it remains to be seen whether we take this on board in our actions and deeds.