Jonathan O’Brien of City Kayaking says they began taking litter out of the River Liffey ten years ago. In that time he’s seen a change in the river.

City Kayaking was launched in order to offer people access to water activities in Dublin, but in the beginning there was a lot of what we used to call ‘legacy litter’ in the Liffey. It would have wildlife underneath it, or bottles would be full of barnacles. We don’t get that anymore. All the litter now comes out pretty clean, quite new. In the summer we take it out so quickly because we’re on the river so often. A McDonald’s bag will blow into the river and we’ll get it out before it’s even wet. Whereas ten years ago people got used to looking at a lot of trash when they saw the Liffey.

Today Jonathan pulls cans, plastic bottles and a few take away containers from the water while motoring up the river. ‘Small amounts of effort every day go a long way,’ he says.

The presence of Styrofoam is a recurring issue. Jonathan doesn’t know where it comes from, but he says it is as common as the seagulls: ‘there’s no pattern to it. It’s just there.’

Jonathan reckons most of the litter comes from the city itself, from along the quays, the boardwalk and new Dockland developments:

We can very easily predict where rubbish is going to be. Daily cleanups are just part of our routine now when guiding kayaking tours. For us, removing litter is a small step to leave the river cleaner than we found it. We’re also chipping away at negative perceptions people may have of the Liffey.

Sadly, Jonathan has encountered little expertise in Dublin City Council for managing this waterway: ‘I don’t see a department in there who are getting their teeth stuck in.’

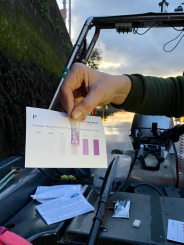

Jonathan and his colleague Jamie have also been conducting tests on behalf of Dublin City University to monitor water quality. Over the past few years they have measured elevated levels of phosphate and nitrate, which washes downstream from farms and comes locally from urban runoff.

This nitrate and phosphate residue is invisible to people walking Dublin’s quays but Jonathan sees its effect on the river’s flora: ‘effectively it fertilises the river. Those blooms of algae grow. They grow very fast, and then they die off. And the secondary effect is that the ecosystem gets hammered.’ This he thinks is ‘a ticking bomb.’

Nonetheless, ‘ Ireland has never had heavy industry. We’ve never had coal or steel in any significant quantities, so we’ve never had the slag and the downstream problems with that.’

Thus, unlike major rivers in other European countries, such as the Thames the Rhine or the Seine, which have had heavy industry situated along them for centuries, the Liffey doesn’t have a long-term legacy of heavy metals or arsenic.

Originally Jonathan’s business found it far easier to get tourists onto their kayaks than to get Dubliners on board.

He now recognises that ‘Dubliners were always looking at the river and thinking it was filthy.’

But drawing attention to the problem of litter was a double-edged sword:

The last thing we needed to do was reinforce the bad reputation the Liffey had as a dirty river. There was a lot of litter, but litter in itself doesn’t make for bad water quality. It’s just litter. It’s like saying that the soil is bad because there’s rubbish on the surface. It doesn’t necessarily make sense. So we never spoke about it. We never tweeted about it. We never put pictures of it out. It’s only recently we’re kind of confident enough that the city’s attitude has changed to the water, that we can say, you know what, collectively we can clean it up.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused an abrupt drop in tourism and City Kayaking’s business, but this period also sparked Dubliners into rediscovering the Liffey and their local green spaces. Jonathan says they’ve seen more locals showing up to go paddling and it’s a trend he wants to continue. He finds the global attitude has changed:

The average Joe is much more environmentally aware than they used to be. They might not know exactly how to help, but they are still supportive of the idea of a sustainable environment. Floating the Liffey is an experience that brings things into focus — the beauty of nature alongside a few stray bits of litter, and our capacity to improve things. We’re not just kayaking, we’re opening minds.

In September 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency released a report demonstrating that water quality declined nationally between 2016-2021. This included a downgrade in the ecological status of the Liffey estuary from “satisfactory” to “moderate” due to phytoplankton, or algae blooms.

With thanks to Jamie Brunkow for editorial assistance.