W.B. Yeats’s poem, ‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’ retains an appeal more than a century after its publication in 1899. Musicians in particular – from Christy Moore to Mike Scott – have been drawn to its magical imagery and measured cadences.

One cruel New Years’s morning a few years ago its opening lines: ‘I went out to the hazel wood, / Because a fire was in my head’, popped into my head after romantic hopes had been dashed the night before. I realised a dose of Nature was the only conceivable cure.

Like Yeats, most of us feel overwhelmed by our racing thoughts at times. Then the sanctuary of a forest or running water can still the mind. Nothing ever feels quite so bad in a beautiful natural setting.

We may also draw lessons there, as in Shakespeare’s play As You Like It, where Duke Frederik finds ‘tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything’.

But what if, instead of a resplendent Nature, we encounter a degraded landscape and poisoned waterways? What message burns into our souls if the hazel woods are reduced to cow fields or sitka spruce plantations, where birdsong is no longer heard?

Even in Yeats’s time there were few of the virgin forests, which once covered the entire island. As Frank Mitchell puts it:

It is hard for us to picture the majesty and silence of these primeval woods, which stretched from Ireland far across northern Europe. We are accustomed to an almost treeless countryside, and if we can find anywhere some scraps of ‘native’ woodland, we are disappointed by the quality of the trees(1).

And the picture is getting worse, with increasing use of chemicals, and intensification of agriculture: the Slow Death of Irish Nature.

Irish agriculture is neither efficient, timeless, nor equitable. It remains afloat because of European subsidies, holding in perma-frost a system designed to satisfy the appetites of the British Empire, enriching a small number of large farmers and industry barons especially, while most farms teeter on the brink.

Structural deficiencies are skillfully concealed from the Irish people by obsequious, and often corrupt, politicians, a desultory education system, and a compliant media. Only the prospect of hundreds of millions in fines for failure to reduce runaway Greenhouse Gas Emissions may save the land from further despoliation; but even one mitigation strategy, of planting monoculture plantations, is eroding biodiversity further.

The exploitation of Ireland’s Nature goes hand in hand with the exploitation of millions of domesticated animals and human beings.

Karl Marx highlighted a disturbed metabolic interaction between human society and the environment under a capitalist system, which he termed metabolic rift. The intensification of agriculture depletes nutrients from soils, which Marx viewed as analogous, and kindred with the exploitation of labour, leading to an alienation from Nature.

II – The Great Hunger

To my knowledge Ireland (North and South) is the only substantial region in the world with a lower population today than in the 1840s. The population peaked at almost 8.5 million, and has only reached 6.5 million today – a considerable rise on the 1950s, when it had dipped below three million in the South.

The steady decline was intimately connected to a shift away from a predominantly mixed agriculture, with an emphasis on tillage and subsistence, to a system based almost exclusively on generating livestock for the Imperial British market.

The catalyst was the Great Famine 1845-1850, although the move away from tillage was also a product of Britain finding cheaper sources of grain after the Napoleonic Wars. Remarkably, according to Amartyra Sen: ‘In no other famine in the world [was]the proportion of the people killed … as large as in the Irish famine of the 1840s(2)’.

The Great Famine was devastating to the three million depending, almost exclusively, on the potato for nourishment. By the eve of the disaster that vulnerable cohort of cottiers and subtenants occupied just one million acres, representing a mere five percent of the of the total acreage of land suitable for agriculture(3).

With twenty million acres available to produce the population’s food, even with the worst conceivable crop failures, an abundance of food could have been grown to feed the entire population. But the market demanded cattle ‘on-the-hoof’, exported live to England, and other livestock products. The land was not the patrimony of the people, but a generally absent landlord class.

To produce and trade commodities for the Empire required a substantial comprador class, who profited from the shift. Famine survivors took advantage of the land clearances as Kerby A. Miller writes:

an unknown but surely very large proportion of Famine sufferers were not evicted by Protestant landlords but by Catholic strong and middling farmers, who drove off their subtenants and cottiers, and dismissed their labourers and servants, both to save themselves from ruin and to consolidate their own properties(4).

Abandoned cottage, County Sligo.

Strong farmers and merchants formed the backbone of the political movements which agitated for possession of the land, and ultimately Irish independence. But tenant ownership and national sovereignty did not reverse the agricultural transition of the post-Famine era. This system depended on low labour inputs for profitability, ensuring a rapid flow of emigration throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth.

Revealingly, when works were undertaken on the substantial farmhouse where my father grew up in Sligo the slates on the roof were dated to the 1840s. It is disturbing to consider a prosperous farmer building his homestead there off the back of wealth from lands seized from smallholders. Joe Lee imagines the effects across much of the country:

They will have seen corpses, if not in their own dwellings, then on the roads and in the ditches. Many are likely to have felt a degree of guilt, of the type that often afflicts survivors of tragedies, not only of the Holocaust, but of events like earthquakes, and mining catastrophes … A sense of guilt can simmer below the surface to perhaps breakout in uncontrollable and, to uncomprehending outside observers, in apparently inexplicable ways(5).

The Irish nation still lives with an echo of this survivor guilt, that has expressed itself in ways we do not yet fully comprehend. One such may have been a distortion of sexuality amidst extreme piety; another perhaps, a loathing for the land itself, still expressed in a ruthless exploitation that often seems wanton in its disregard.

III – Irish Farming Today

Teagasc’s recent National Farm Survey for 2017 revealed there were 84,599 farms in Ireland, with an average of income of €31,374. Of these 15,639 were dairy farms with an average income of €86,115. There were a mere 7,387 tillage farms (many growing feedstuffs for livestock), with an average income of €37,158. The remainder – three quarters of all farms – were (dry) cattle and sheep farms, with an average income under €15,000. Indeed, thirty-five-per cent turned a profit of less than €10,000.

According to the report (on p.5): ‘In general, farm income continues to be highly reliant on direct payments. In 2017 the average total payment received was €17,672 per farm, this accounted for 75% of average farm income.’

Remarkably, on an average dry cattle or sheep farm over 100% of ‘income’ derived from direct payments (subsidisation), while almost €20,000 of an average dairy farm’s substantial earnings, came from subsidies. It is a truly dysfunctional system.

Seventy-five percent of Irish farms would go out of business overnight under a free market, while a small number of already wealthy farmers receive subsidisation totalling approximately €300 million.

The government has committed to expanding agricultural production, particularly the dairy sector, under a report entitled, without irony, FoodWise 2025. However, a 2018 Teagasc report admits that these aspirations will ‘provide a significant challenge to meeting emissions targets, particularly as agriculture comprises one-third of national emissions and 44% of the non-Emission Trading Sectors (non-ETS).’

Revealingly the image chosen by the authors of the plan does not reveal a single tree or bush.

A growing proportion of Ireland’s agricultural products (including the thousands of animals shipped abroad in appalling conditions) are exported to non-EU states, including undemocratic regimes such as those in Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Turkey. The powdered milk market is of particular importance, with Ireland the second leading exporter to China, after New Zealand. Exclusive Breastfeeding is recommended by the WHO for babies up to six months of age.

Ireland grows little of its own food, relying on exports for the majority of fruit and vegetables the latter of which, remarkably, form less than 1% of overall energy intake, a deficiency linked, in all likelihood, to the obesity pandemic(6).

Contrary to the portrayal of Ireland as ‘the Food Ireland’, the country is actually a net importer of food calories, making us vulnerable to food ‘shocks’, including major storm events – such as the recent ‘Beast from the East’, when supermarkets supply chains failed. Yet Ireland’s temperate climate is suited to year-round cultivation of a wide variety of crops.

The beef industry has been subject to a succession of scandals over decades, including what amounted to a government bail out for Goodman International in the early 1990s. More recently we saw horse meat being substituted for beef. The industry has enriched a small number of barons, especially Larry Goodman who had an estimated net worth, along with his spouse, of €706 million in 2015. It would take the average dry cattle farmer, on €15,000 per annum, 47,000 years to accumulate that fortune. The disparities in wealth in Irish farming are probably greater now than ever.

The main farming organisation, the IFA advocates on behalf of an increasingly obsolete system, where food prices for consumers are so high that Tesco’s executives reportedly referred to the country as Treasure Island; while ruining the environment, and leaving most farms on the brink of collapse.

In 2015 that organisation was rocked by revelations that general secretary, Pat Smith, had received pay and perks worth some €1m for 2013 and 2014. For good measure, his payoff amounted to €2m. Just as eye-watering for ordinary farmers was how then IFA president, Eddie Downey was receiving almost €200,000 annually, some eight times the average farmer’s income at the time.

Most disturbingly, however, is the extent to which the state projects a green image for Irish farming, using taxpayers money, through the Origin Green advertising campaign, which the Irish Wildlife Trust has described as a sham.

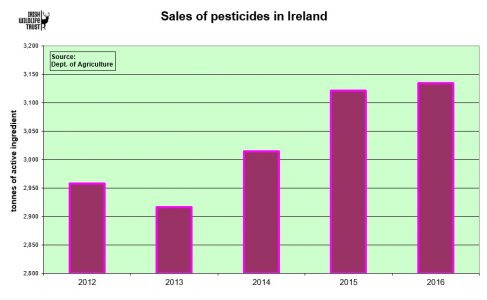

As part of a global insectaggedon, pesticide use has continued to climb in Ireland, posing grave dangers to essential pollinators. A third of Irish bee species could soon be extinct. According to Professor John Breen Irish grasslands are useless for bees: ‘Intensification of our farming is the key issue,’ he says. ‘It has taken a toll.’

Meanwhile half of Ireland’s waterways are now polluted, mainly by farm run-offs.

The long-term prognosis for Irish agriculture is extremely bad. The system cannot endure indefinitely. We are leaching the soil of nutrients, and contributing significantly to Climate Change, while exploiting the understandable desire of farm families to stay on their land.

Exploitation of the landscape of Ireland goes hand in hand with the exploitation of most farmers, confirming Marx’s theory of metabolic rift. Farmers should instead be supported to restore biodiversity, and grow crops, primarily for local consumption, both of which would be long term investments in the health of the population.

IV – Returning to the Source

‘The Song of Wandering Aengus’ is an imaginative vision for Ireland, reinvented as a glimmering girl. Yeats was singing a nation into being. But he would later bemoan the death of Romantic Ireland, as a rising class of Strong Farmers and their heirs, whose sons entered business and the professions, fumbled in greasy tills, adding the half pence to the pence, and prayer to shivering prayer.

The 1916 Rising claimed the land of Ireland to be the patrimony of the people, but the interest of individual property owners has long held sway, under a 1937 Constitution that has been interpreted to favour the wealthy, as opposed to the common good.

It was on one memorable journey, which I took during my early twenties, that I woke up to the damage being done to our environment.

The morning after the night before, I felt overwhelmed by Dublin life, and determined to proceed by foot to find a sanctuary away from the city. I would find a spot to camp, removed from the banter, bright lights and braggadocio.

I proceeded south through drab suburbs punctuated by ugly strip malls, attesting to poor planning in the city’s hinterland. I crossed a wide and ominous motorway under construction that became the M50, and proceeded to climb hills beyond the city limits; an endeavour increasingly fraught on roads lacking footpaths.

As cars shot by spewing noise, pollution and anger, I chose to proceed off-piste. After scaling fences and passing through a few deserted cow fields, I encountered ugly groves of immature spruces being fattened, like turkeys, for the satisfaction of a North American Christmas fantasy.

Eventually the terrain grew sparser, boggier and less fenced-in. At last I met a variety of deciduous trees; the spectacle a sprawling magnificence of autumnal colours as my legs wearied under the strain of my pack.

I began to collect firewood as I proceeded, soon gathering a sufficient quantity for my purposes. At last I reached the source of the River Dodder, a tributary of the Liffey, which passes within a hundred metres of my family home. Unconsciously, I was reaching back into my own origins, and I felt a spring in my step.

As the light declined, waves of midgies brought crass irritation to my reveries, but soon the sun had disappeared altogether, and smoke from the fire deterred my tormenters. I prepared a meal consisting primarily of potatoes – the food of our impoverished ancestors –that I wrapped in tinfoil and cooked in the ashes of the fire.

All about was a glorious silence, and the stars, usually masked by urban light, appeared as a hidden script that I had failed to notice. At last I felt at home.

(1) Frank Mitchell, Reading the Irish Landscape, (Dublin, 1990), p.89.

(2) Amartya Sen, Identity and Violence: the Delusion of Destiny, (New York, 2006), p.105.

(3) Raymond Crotty, Irish Agricultural Production (), p.85.

(4) Kerby Miller, ‘Emigration to North America in the era of the Great Famine’, in Crawley, Smyth and Murphy, Atlas of the Great Famine ( p.221.

(5) Joseph Lee, ‘The Famine as History’, in O Grada, Famine 150: commemorative lecture series, (Dublin, 1997) p.168-9

(6) Colin Sage, Tara Kenny Connecting agri-export productivism, sustainability and domestic food security via the metabolic rift: The case of the Republic of Ireland (2017), p.19

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S245226351730006X