This is the first of two articles occasioned by the recent publication of Periodicals and Journalism in Twentieth-Century Ireland 2: A Variety of Voices, edited by Mark O’Brien & Felix M. Larkin and published by the Four Court Press in Dublin. Here, Frank Armstrong reviews the first instalment in this illuminating study, Periodicals and Journalism in Twentieth Century Ireland: Writing Against the Grain (2014) edited by the same authors.

In their introduction to the first volume the editors stress the importance of what were often minority publications – generally with brief lifespans – to cultural and political developments in the Irish State and beyond; describing them as ‘the fulcrum on which the intellectual foundations of Irish society moved – slowly, but irrevocably.’ Their contents often anticipated ideas and movements that would go on to gain greater popular adherence, and their varied approaches remain an inspiration to contemporary journalists.

Movable Type.

“More formidable than a thousand bayonets”

Most of those living through a Print Revolution in Europe after 1450 were unlikely to have been awake to seismic changes occurring in how information was being distributed and absorbed. Johannes Gutenberg’s invention, the first of its kind in Europe, as well as increased availability of paper, foregrounded the Renaissance and Reformation; increasing literacy levels and consolidating a few dominant vernacular languages through new literary forms, especially the novel and then, increasingly, newspapers, magazines and periodicals.

From as early as the seventeenth century newspapers, magazines and periodicals were being published. A newspaper is printed matter acknowledging – unlike haughty books – its obsolescence ‘on the morrow of its publication’[i], as Benedict Anderson put it. Ireland’s first newspaper, devoted to foreign affairs and political intelligence, The News-Letter was published in Dublin in 1685.

By the early nineteenth, Napoleon described a journalist as ‘a grumbler, a censurer, a giver of advice, a regent of sovereigns, a tutor of nations,’ concluding that ‘four hostile newspapers are more formidable than a thousand bayonets.’ Newspapers were crucial to directing or even forging collective identities such as the nation.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the powerful – whether state bureaucracies or dominant corporations – have long sought to control their offerings, and by extension journalism itself, through the carrot of patronage and advertising, and the stick of censorship and outright suppression.

Traditional newspapers are also tangible products to be sold. Thus, proprietors stimulate demand especially through headlines demanding attention. The daily cry of the newspaper boy summoned a new scare or disaster – yellow journalism has long antecedents – downplaying or ignoring certain facts, while amplifying or even inventing others; often preying on fears and prejudices, just as click bait does today.

Becoming a Thing

Alongside meretriciousness and outright propaganda journalism provides an opportunity for visionary – or delusional depending on your outlook – editors and writers who believe in the capacity of collections of regularly published print materials – generally containing short form articles aimed at the general public – ‘to speak truth to power’, ‘move hearts and minds’ and expose hypocrisy and corruption.

This form of idealistic journalism most frequently appears in magazines or periodicals that may succeed in eschewing obsolescence, even if it is ‘printed on lavatory paper with ink made of soot’, as Sean O’Faolain the former editor of the Bell memorably described the low-cost approach of his publishers.

With a longer shelf life, the magazine or periodical falls somewhere between the immediacy of the contents of newspapers and the greater durability of ideas contained within books. As Joe Breen puts in his article on Hot Press: ‘One of the great strengths of periodicals is that by operating outside the routines and demands of 24/7 news-flow, they are afforded the space and grace to react thoughtfully to events.’

To succeed, such publications usually require the guiding hand of a charismatic, single-minded and tireless personality as editor. The social historian Edward Hyams once observed how:

When a journal is started, a number of minds combine under the dominion of one, the editor’s, to bring it into existence … What the editor and his colleagues have to do is contrive to make such disparate materials as news, views, fiction, criticism, poetry, even competitive word-games, jell into coherence … if this be done successfully then, after… a certain number of issues, the new paper takes on a quality, which is indefinable, and which is apparent, for example, in a work of art or well-designed machine … At that point the paper, to exaggerate a little, becomes a thing…

Thus, in their introduction to the first volume of Periodicals and Journalism in Twentieth Century Ireland the editors observe of their subject matters covered: ‘The most obvious common feature is the omnipresence within each of them of a dominant personality, or two – as editor and/or proprietor.’ The problem with such an approach is that if the guiding hand is lost these publications may struggle to endure.

The failure of the #JustSociety movement within #FineGael was a turning point in Irish history. David Langwallner recalls the contradictory career of Declan Costello.https://t.co/RdNsjfXqJX@broadsheet_ie @ConorBlenner @vincentbrowne @LumberBob @KevinHIpoet1967 @liamherrick

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) May 11, 2020

A Docile Lot

Michael O’Toole observed that up to the 1960s in Ireland journalists had been ‘a docile lot, anxious to please the proprietor, the advertiser, the prelate, the statesman’. This era was, he argued, characterised by ‘an unhealthy willingness to accept the prepared statement, the prepared speech, and the handout without demanding the opportunity of asking any searching questions by way of follow-up.’ The fundamental defect of Irish journalism during this time was, he noted, ‘its failure to apply critical analysis to practically any aspect of Irish life.’

Terence Brown was harsher still, noting that ‘almost all Irish journalism in the period had contented itself with the reportage of events and the propagandist reiteration of the familiar terms of Irish political and cultural debate until these categories became mere counters and slogans often remote from actualities’. While in 1935, the novelist Frank O’Connor declared that Irish daily newspapers were ‘intolerably dull’, were ‘not trying to educate the public’, and ‘trying to camouflage reality.’

The editors of Periodicals and Journalism in Twentieth Century Ireland, however, assemble those rare, eccentric, publications ‘providing an outlet for those writing against the grain of mainstream Irish society’, who ‘made freedom of expression a reality’ and created a ‘space for diversity of opinion’.

Importantly, they argue that ‘the influence they had via that readership was entirely disproportionate to their circulation levels and profits, if any. They were the fulcrum on which the intellectual foundations of Irish society moved – slowly, but irrevocably.’

Prior to the Irish Revolution ultimately led, as Kevin O’Higgins memorably put it by ‘the most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution’ an ideological ferment was articulated through a variety of seminal publications. Certain contemporary political strands can be traced to the twilight of the British administration in Ireland. At that point journalism was characterised by anything but the grey philistinism of the post-independence era.

Articles by Colum Kenny, Regina Uí Chollatáin, Patrick Maume, Sonja Tiernan, James Curry and Ian Kenneally in this volume consider Sinn Féin, the United Irishman and others under Arthur Griffith’s editorship, Irish language publications such An Claidheamh Soluis edited by Eoin MacNeill, D.P. Moran’s The Leader that lasted until the early 1970s, the suffragette Irish Citizen, primarily edited by Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, and James Connolly’s The Worker.

Finally, there is The Irish Bulletin, a publication produced by the first Dáil, offering what might be described as well-intentioned propaganda – insofar as its (truthful) contents was aimed at a particular readership and served a clear strategic purpose.

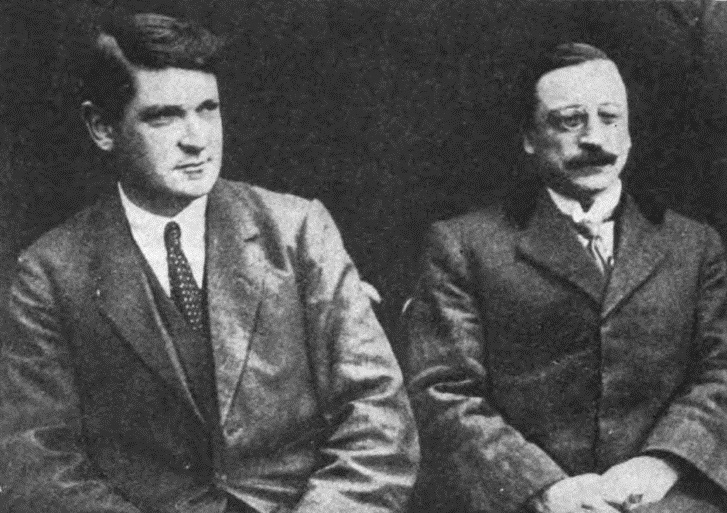

Arthur Griffith (right) with Michael Collins.

Arthur Griffith

James Joyce ‘said that the United Irishman was the only paper in Dublin worth reading, and in fact, he used to read it every week.’ Griffith, according to Joyce:

was the first person in Ireland to revive the separatist idea on modern lines … A great deal of his programme perhaps is absurd but at least it tries to inaugurate some commercial life in Ireland … what I object to most of all in the paper [Sinn Féin] is it is educating the people of Ireland on the old pap of racial hatred whereas anyone can see that if the Irish question exists, it exists for the Irish proletariat chiefly

Mischievously, Joyce had a character in Ulysses claim that Bloom ‘gave the idea for Sinn Fein to Griffith to put in his paper.

Undoubtedly, Griffith was a formative influence on Irish nationalism, and it is indicative that his paper incubated the most enduring political movement – Sinn Féin (ourselves) – on this island. This combined, at times uneasily – hence the splits – a somewhat fuzzy ethnic nationalism with a go-it-alone petit-bourgeois mentality, alongside a visceral anti-colonialism that eschewed strict ideology.

Griffith was a bundle of contradictions. A great writer – ‘an inspired journalist who combined style and temper in a way no one else could match’ according to F.S.L. Lyons – disinterested in literature that did not strengthen the nationalist outlook. Thus, he disdained Synge’s Playboy of the Western World that dared to question certain nationalist orthodoxies.

Moreover, Griffith wrote sympathetically about the plight of colonised Africans, while excusing his hero John Mitchel’s reactionary views on slavery. His anti-Jewish statements leave him open to a charge of antisemitism, and even proto-fascism, yet he argued in favour of a Zionist state in Israel.

Despite highlighting poverty, Griffith was antagonistic towards international socialism, suspecting British trade unions of weakening nationalist statements. If he had lived into the 1920s, however, it is questionable whether he would have supported the free trade policies of the first Cumann na nGhaedhal administration.

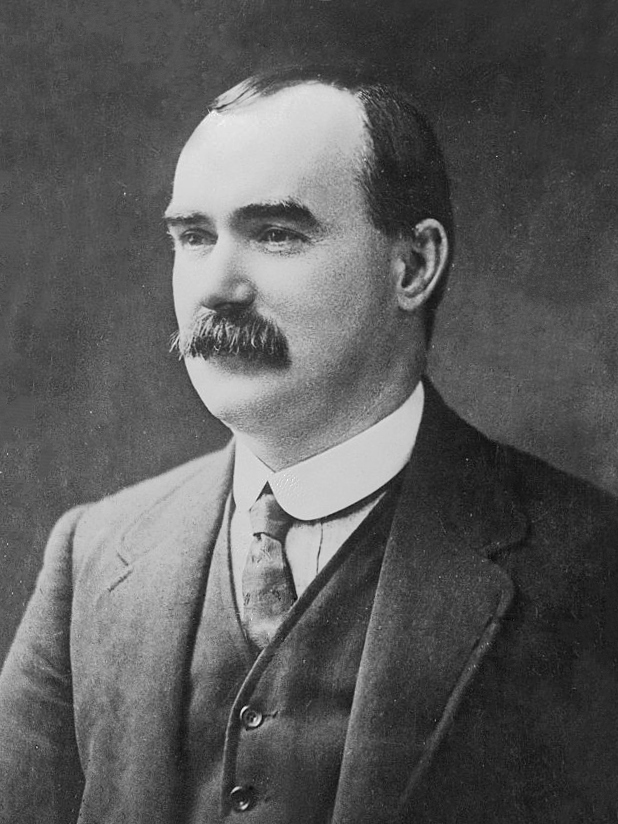

James Connolly

Challenging Authority

The more radical political strains that emerged at this time were less evident in the post-independence period. Nonetheless, they provided a lasting body of opinions that served as an inspiration for future movements: the fulcrums “on which the intellectual foundations of Irish society moved – slowly, but irrevocably.”

According to Sonja Tiernan the suffragist Irish Citizen was ‘edited by men [notably Francis Sheehy-Skeffington]so that women could devote their energies to political campaigns’. It combined feminism with a radical pacifism that put it at odds with, among others, Emmeline Pankhurst (though not her daughter Sylvia) who supported the British government’s recruitment drive.

Francis’s wife Hannah pointed to the sacrifice of mothers who had to ‘deliver up the sons they bore in agony to a bloody death in a quarrel of which they know not the why or the wherefore, on the particular side their Government has chosen for the moment.’

Francis organised anti-military meetings in Dublin, at which he argued that the leader of the main nationalist party in Westminster, John Redmond, simply ‘sold Irish people to the British army for nothing’ Recalling the old nationalist cry of England’s difficulty being Ireland’s opportunity, on 23 May 1915 he declared ‘Anything that smashes and weakens England’s domination of the seas is good for Ireland. Germany has never done us any harm. The only power that has ever done us any harm is England.’

He would be arrested under the Defence of the Realm Act, and was ultimately murdered by a deranged British officer during the 1916 Rising.

Another revolutionary editor of this period was one of the leaders of the 1916 Rising itself, James Connolly, who would later rage about how he had been the editor of ‘the only paper in the United Kingdom to suffer an invasion of a military party with fixed bayonets and to have the essential parts of its printing machine stolen in defence of freedom and civilisation.

According to James Curry his ‘Irish Worker was a crusading paper of vitality that adopted a forcefully direct journalistic style to ensure readers understood its stance at all times’.

The industrialist William Martin Murphy – apparently ‘the most foul and viscous blackguard that ever polluted any country’ – was regularly in its crosshairs.

In response to alleged German atrocities, Connolly instead concerned himself with those perpetrated by ‘capitalist barbarians’ closer to home, arguing that the Dublin housing crisis was destined to be forgotten ‘amid the clash of arms, and the spectacular magnificence of international war’.

In his article ‘The Huns in Ireland’, which led to the paper’s suppression, he argued:

The steadily increasing cost of the necessaries of life since the war began brings home to the mind of even the most unreflective amongst us, the utterly heartless nature of the capitalist class … The enemy is within our gates. We need fear no Hun from across the waters of the North Sea.

It is notable that James Connolly’s anti-war rhetoric is recalled by Irish activists today.

A group of Black and Tans and Auxiliaries outside the London and North Western Hotel in Dublin following an attack by the IRA, April 1921

The Irish Bulletin

To achieve independence the government of the first Dáil dedicated significant efforts to garnering sympathy from an international, including moderate British, audience by highlighting the atrocities committed by British forces: the dreaded Black and Tans and Auxiliaries. This was achieved primarily through an underground publication: The Irish Bulletin, 1919-21, which apparently caused consternation in British government ranks. Thus, in Parliament, the chief secretary for Ireland, Hamar Greenwood, claimed that ‘critics were being duped by a mendacious Irish periodical’

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Arthur Griffith was active in its early days, but Desmond FitzGerald became a guiding influence thereafter. Its power lay in its credibility. Ernest Blythe recalled how FitzGerald:

resisted the pressure to which he was constantly subjected from most quarters in favour of painting outrages by British forces in a blacker hue than was justified by the facts …. The result of this attitude and the personal impression that he made was that independent foreign pressmen who admired and trusted him did ten times as much to make Ireland’s case known throughout the world as would have been done if the advocates of heavy expenditure had their way or if a less transparently honest man had been in charge of propaganda.

It goes to show that facts can speak for themselves, and that exaggeration may only diminishes a publication’s credibility.

Taste for Comedy

Dublin Opinion (1922-68) styled its humour the ‘safety vale of a nation’. Its relative success attests to an enduring appetite for humorous takes on serious political events, such as we still see today most obviously in publications such as Waterford Whisperers. This apparently timeless Irish tendency to laugh at absurdities on the political stage is, however, often to the exclusion of more serious assessments. Thus, Felix M. Larkin argues that Dublin Opinion‘s humour ‘concentrated on the political to the detriment of the social and economic.’

Nevertheless, there is some truth to the couplet carried in early issues: ‘Not seldom lurks the sage’s cap and gown / Beneath the motley costume of the clown’.

Dublin Opinion played an important role in puncturing the reputation of Eamon de Valera, scorning his ‘professed belief that he had a unique insight into what the people of Ireland wanted.’

Larkin argues that the publication ‘probably saved proportional representation in 1959, and it inspired T.K. Whitaker to write his seminal ‘Grey Book.’

The renowned civil servant T.K. Whitaker said that he was impelled to undertake his famous white paper the First Programme for Economic Expansion in response to the cover cartoon in the September 1957 edition of Dublin Opinion in which the young female figure of Ireland instructs a fortune teller, peering into a crystal ball: ‘Get to work! They’re saying I have no future.’

It also, arguably, exhibited a healthy suspicion of farmers, who are ‘seen filling out forms for grants… duping government inspectors, joining myriad associations to protect their interests, smuggling cattle across the border with Northern Ireland and constantly complaining.’

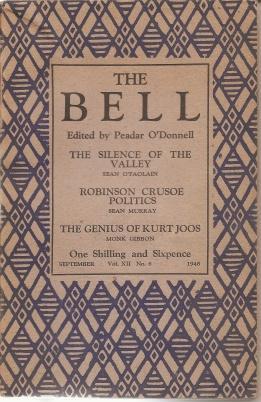

The Bell

Probably the most important publication of the post-War period in terms of its inspiration to future journalists was The Bell, under Sean O’Faolain as editor.

Ironically funded in part by an investment by sweepstakes millionaire Joe McGrath, it was inspired by leftist UK publications that emphasised the importance of factual reporting. O’Faolain opined that ‘Generalisation (to make one) is like prophecy, the most egregious form of error, and abstractions are the luxury of people who enjoy befuddling themselves methodically’. Contemporary editors are still inclined to advise journalists “to show it, don’t tell it.”

Covering generally overlooked themes such as the ongoing challenge of tuberculosis, many of its articles were created, according to O’Faolain, by ‘somebody [who]had to out with a notebook and listen, and encourage and make a record. The poor would for ever remain silent if people did not, in this way, wrench speech out of them’

O’Faolain also bemoaned an enduring disconnect between academia and the general public: ‘with only one or two honourable exceptions our professors never open their mouths in public.’

Mark O’Brien concludes that it ‘played a central role in prompting journalism to develop beyond the confines of party affiliation’, an endeavour ‘taken up with gusto by the Irish Times in the early 1960s’, especially through Michael Viney.

Sean O’Faolain

Hibernia

According to Brian Trench under John Mulcahy Hibernia, became a strong presence in Irish media as an independent, frequently dissenting voice. Indeed, ‘by 1973 it was already carrying articles alleging conflicts of interest and possible corruption in relation to the activities of local politicians in the Greater Dublin area.

The magazine became a platform for dissenters such as Raymond Crotty, Desmond Fennell, Ernest Blythe and Proinsias Mac Aonghusa.

Terry Kelleher a Hibernia journalist between 1970-75 recalls Mulchay’s ‘questioning approach to everything and everyone, but especially towards those in a position of authority. Every institution, whether it be a political party or financial grouping, artistic clique or academic ivory tower, all must be challenged, their continued existence questioned.’

The magazine gave particular attention to stories of’ bad planning, illegal property development, councillors’ conflicts of interests and related issues,’ as well as the mistreatment of prisoners by the Royal Ulster Constabulary at a point when an anti-Republican Revisionism was increasingly prevalent in Irish intellectual circles.

Hibernia went where most newspapers dared not go, at one point revealing that a sitting member of the Special Criminal Court was falling asleep on the job. According to Trench, ‘Irish Times journalists Peter Murtagh and Joe Joyce later dealt with this incident … though they omitted to mention that their own newspaper – like the other dailies – chose not to refer to what was happening in front of them.’

Mulcahy’s unschooled approach of relying on tip offs brought criticism. Vincent Browne claimed the publication had ‘a style that may lack the investigative edge required by a serious paper.’

However, when the publication closed after one libel action too many, Pat Smyllie wrote in the Irish Times that ‘whether you liked it some weeks or not, it was brave, searching, cheeky outrageous but … essential to many of us’. He noted that it sometimes had to pay the price in court for uncovering ‘double dealing’.

According to Niall Kiely the magazine was a ‘must-read’ for journalists in the mainstream media: it was a source of information and perspective not found elsewhere.’

Another legacy, argues Trench is the ‘almost universally cynical tone of the anonymous journalism in The Phoenix may be considered an unfortunate and partial legacy of Hibernia.’ However, given the endemic corruption of the period, and beyond, and an apparent acquiescence to this in the mainstream media, such cynicism might be forgiven.

Hot Press Magazine

Rock n’ Roll

Jon Street notes that ‘music plays a part in our constitution as moral beings and in our constitution as political ones. In responding to and in evaluating music we do not just give expression to our tastes, but to our political values and ideas. Music is, to this extent, part of the way we think politically.’

According to Diarmuid Ferriter the value of Hot Press lay in ‘its value lies in the extent to which it highlighted the burgeoning youth culture of the era as well as new musical departures and a determination to embrace international influences.’

Its remarkably durable editor, Niall Stokes acknowledged that 1977 – according to Jon Savage the ‘moment of high punk’ – was ‘not the most healthy climate in which to launch a newspaper.’ He championed a liberal social agenda – which was very much in the minority at that point – along with his editorial partner (and wife) Máirín Sheehy and brother Dermot Stokes.

Stokes said: ‘We felt in particular that the deference shown to the Roman Catholic Church in all areas of Irish life, including the media, was entirely inappropriate.’

The U2 connection is central to the story of Hot Press, while John Waters, a young aspiring journalist then living in remote Roscommon, was an important recruit. According to Stokes: ‘Back then, John, I think it is fair to say, saw himself as a leftist’. For his own part Waters reckons: ‘I can say with absolute certainty that I would not be writing today were it not for [Stokes].’

An important feature was the Hot Press interview, where according to Waters: ‘The idea was to ‘get under the skin’ of people who were known in a certain context.’

An interview with Charles Haughey ‘caused a huge reaction in the mainstream media as the Fianna Fáil leader’s use of expletives and colourful descriptions of opponents broke with convention.’

Vincent Browne.

Magill

In 1986 The Guardian newspaper recorded that ‘Magill has gained a political influence that has no parallel in British or indeed European magazine publishing,’ while the Sunday Times credited it with ‘dragging Irish journalism out of its largely comfortable, unquestioning dullness’.

According to Kevin Rater it was ‘shaped by the particular interests of its proprietor and founding editor, Vincent Browne’, who wrote in 1969: ‘In terms of its wealth, Ireland cares less for the weaker and poorer sections of its community than any other country in Europe with the exception of Portugal. Yet the popular myth is that there is no poverty in Ireland.’ Party politics, the redistribution of wealth and Northern Ireland would be its primary focus.

Browne shared editorial responsibilities with Mary Holland, who later claimed Browne: ‘could be very cruel to people and didn’t seem to expect them to take it personally.’

According to another journalist, Paddy Agnew: ‘the cover was the most talked about, and the most agonising thing, every month. It was torture.’ Britan Trench recalled: ‘He would snort and sniff at content ideas. And then his view of the would emerge’.

At the end of Browne’s tenure as editor Colm Tóibín was appointed to the role. He was influenced by the ‘new journalism’ in the work of American writers such as Tom Wolfe, Gay Telese and Hunter S Thompson’. Another editor, Fintan O’Toole brought ‘an extraordinary range and depth of interests.’

Ultimately, according to Rafter ‘It was outflanked on one side by The Phoenix with its mix of business and political gossip and on the other by the national newspapers that had adapted their editorial offerings to include longer articles, many by names who had first emerged in Magill.’

Image (c) Daniele Idini.

Granular Analysis

Magazines and periodicals share certain features with independent restaurants, insofar as neither tend to last very long, and are often dependent on a dominant personality, who regularly loses their shirts. Like independent restaurants they perform vital roles for a cultural avant-garde, incubating new tastes and literary styles, which the fast or convenience daily newspaper purveyors often appropriate.

Moreover, it remains the case in Ireland that most investigative journalism occurs at a remove from mainstream daily publications.

As adverted to, a second review of the latest volume in this series provides a more granular assessment of these publications, including magazines representing feminism and gay rights, and focuses on particularly illuminating stories, such as the nature of Irish humour and the state of the press. It will also afford a chance to reflect on the challenges of publishing in our contemporary digital environment.

[i] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso, New York, 2006), pp. 34-35

Featured Image: Dublin, 1916, prior to the Rising.