I’m living in cloud cuckoo land

And this just feels like

Spinning plates

Radiohead, Like Spinning Plates, Amnesiac 2001.

Ten years on from the Irish Banking Crisis and the subsequent taxpayer funded bailouts, how are we faring in term of regulating the financial sector?

In view of the possibility of another property bubble, it is surely vital to ensure appropriate access to justice, especially for those with limited resources.

Prior to the Crash, banks through their own internal regulatory mechanisms – including risk management and third party auditing firms – were, essentially, allowed to regulate their own affairs, which unfortunately permitted a lax regime.

On a rare occasion that a risk manager signalled grave breaches of conduct to the Central Bank of Ireland – as in the case of whistle-blower Jonathan Sugarman – he was largely ignored. And, even though thanks to his revelations we know a great deal more than we would otherwise about widespread banking mis-conducts, Sugarman subsequently had his professional and personal life destroyed. That message is surely not lost on colleagues intending to pursue a similar course.

Back then, inadequate regulatory frameworks allowed underestimation of risk and outright profiteering in the banking sector. Yet there are reasons to believe that, despite the successes boasted of by the regulators, thousands of people are still being failed by the State.

Despite concerns being raised in February, 2021 by Sinn Fein deputy Pearse Doherty that “2,865 complaints to the Financial Ombudsman remain unsolved for over 12 months” very little attention has been paid in the media to enduring dysfunctions in consumer protection frameworks, potentially affecting hundreds of thousands of consumers of financial services.

Regulatory Capture

Regulators come in two types: smart and dumb. The latter are more likely to make mistakes, and the market will learn about mistakes when firms squawk.

Ernesto Dal Bó in the Oxford review of economic policy, Vol.22, NO.2

Could this be a subtle example of so-called ‘regulatory capture’, which is said to occur when a particular industry holds an excessive level of influence over a statutory agency designed to monitor and regulate it?

Ernesto Dal Bó offers two interpretation of the phrase:

According to the broad interpretation, regulatory capture is the process through which special interests affect state intervention in any of its forms, which can include areas as diverse as the setting of taxes, the choice of foreign or monetary policy, or the legislation affecting R&D.

According to the narrow interpretation, regulatory capture is specifically the process through which regulated monopolies end up manipulating the state agencies that are supposed to control them.

Either of these descriptions could easily be used to describe successive Irish government’s cosy relationship with foreign multinationals. Witness how in 2016 then Taoiseach Enda Kenny unashamedly set out Ireland’s stall as ‘the best small country to do business in’. Attracting financial service companies to a friendly, relatively unregulated, environment appears to remain high on the government’s agenda.

But insofar as this is a legitimate goal, the way it is achieved, for example, by perpetuating dysfunctions in regulatory mechanisms, have grave consequences for the public at large, especially in terms of access to justice.

Ombudsman

One mechanism to provide access to justice is embodied in the role of the Ombudsman.

This word come from Sweden where its first use is recorded in the 19th century. Meaning “Commission Man”, it involved oversight over the abuse of power by public administration. The position evolved with changing times and industries, to become globally adopted, assuming the part of an impartial mediator between individual complainants and large, well-resourced organizations.

To give a simple example with a bit more context: what if you have a complaint against the misbehaviour of a credit institution with which you have a resulting outstanding debt?

In Ireland, anyone in such a predicament can avail first of internal complaint procedures within the credit/insurance/pension providers. If this proves futile, as often seems to be the case, you can either go to the Financial Services and Pension Ombudsman (FSPO), or for the better-resourced, proceed directly to the courts.

The FSPO was established in order to provide “an impartial, accessible, and responsive complaint resolution service that delivers fair, transparent and timely outcomes for all our customers, and enhances the financial services and pension environment.”

It’s role is crucial in ensuring basic standards of consumer protection especially in a sector such as financial services, which bears significant responsibility for a dysfunctional property market

This article is not disputing that the Office has fullfilled aspects of it’s responsabilities to date, and recognises the challanges of the past two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Office’s results are well presented in their annual digests of decisions, and were compellingly illustrated by the current Head of the FSPO, Ger Deering, in his Opening Statement to the Oireachtas Petitions Committee the 25th May 2021.

What we are interrogating is why a large number of complaints, seem to have been closed in preliminary scrutiny on a narrow, legal interpretation of the Act. It is also unclear whether the FSPO is sufficiently staffed and organized to make use of the necessary banking knowledge in order to fulfil all its statutory duties.

Boasting Figures

Ben Hoey, an experienced ex-banker who founded Quartech services, a mortgage mis-selling advisory firm, has been assisting individuals with the filings of such complaints and has made us aware of some of the challenges encountered.

Having submitted over fifty complaints over the last two year to the FSPO, as well as two FOI requests in June 2021 and most recently a judicial review, he also raises serious concerns over the ability of FSPO to carry out its duties.

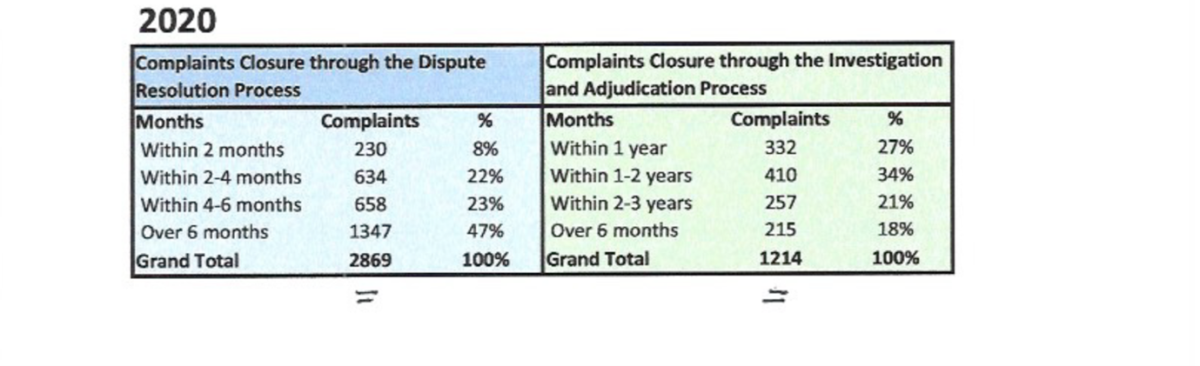

In an Opening Statement to the Oireachtas Petitions Committee, Mr Deering boasted: “In 2020, I am happy to report that, despite the challenges of the pandemic and remote working, we closed 6,193 complaints, an increase of 35% on 2019.”

But thanks to Hoey’s FOI requests, we now know that 2,110 of these cases never entered the dispute resolution or investigation processes.

Those numbers also slightly differ from the ones found in the annual report of 2020, and are presented in a way suggesting that 1,401 cases were actually sorted within a very short time frame.

There are, undoubtedly, cases that were legitimately rejected as indicated in the Act. But in order to gain more detailed explanations for preliminary decisions, made in the first registration and assessment phase, the FOI requested documentation and records in relation to reasons for closure. Unfortunately, in this case the answer was ‘no records exist.’

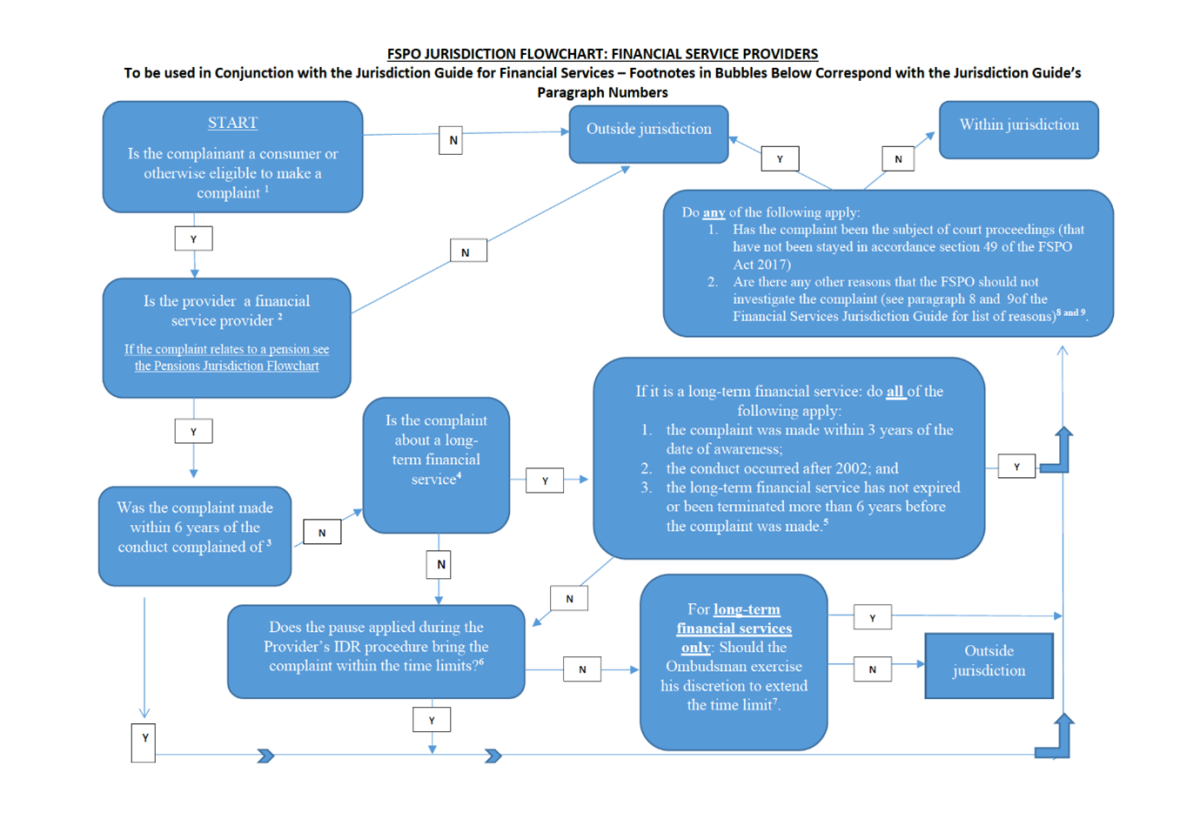

This is just the first stage of the complaint; the staff needs to interpret the Act and establish if the newly arrived complaint falls within the FSPO jurisdiction.

It relies on training and guidance materials, which have also been released, and from this we see that when issues of jurisdiction arise, there is an over-reliance on the legal profession and a marked absence of the necessary banking expertise.

In general, we know that if a complainant does not accept the preliminary rejection, and responds in writing, he or she receives a letter issued by the legal department. But in order to interpret and respond to this one would likely require legal advice.

This doesn’t come cheap as the FSPO is well aware, since it spent €1.8m (46% of staff costs) on “Legal Fees” according to their 2020 accounts. By comparison the equivalent UK body filed no such expenses. Recall that the role of an Ombudsman is to be an impartial mediator between individual complainant and large, well-resourced organizations.

Some of Ben Hoey’s clients received letters up to twenty-two pages long, containing dense legal terminology, supporting FSPO arguments not to investigate; rather than a professional financial analysis of the issue in question.

Others have seen their complaints dragged out for years, stuck in the earliest phase of the “statutory complaints procedure”; which was established in order ‘to afford complainants an informal, expeditious and independent mechanism for the resolution of complaints.’

From the point of view of some complainants, it feels as if the process of adjudication has been designed to keep their case out of the FSPO jurisdiction, thus keeping the number of cases that the Office investigates to a minimum.

When the Financial and Pension Ombudsman positions were merged into their current form in 2018, the new organisation should have been structured, and staffed, to handle a increasing number of annual complaints. It appear from the latest annual report that this has been achieved, but when we get into the granular detail, we see that up to a third of these may have been inadequately handled.

Given that a significant percentage of such disputes are in relation to mortgages and to a dysfunctional housing market, we can surely appreciate the importance of such an institution.

The stigma attached to debt is a deep scar that afflicts many in an apparently prosperous country. Given that a level of responsibility lies with the lending industry, we should expect the Department of Finance to ensure that the relevant agencies such as the CBI and the FSPO that protect such individuals are adequately resourced.

Yet the total count of full time employees of the FSPO is just 85 as of the end of 2021. That amounts to roughly twenty staff per million inhabitants in Ireland. By comparison, its counterpart in the UK employs double that with 3,000 staff, or approximately forty-four per million.

A Stairway to Heaven

Since Ger Deering was recently nominated by the Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform, Michael McGrath, to become Ombudsman and Information Commissioner, we expect that the position of Head of the FSPO will soon become vacant.

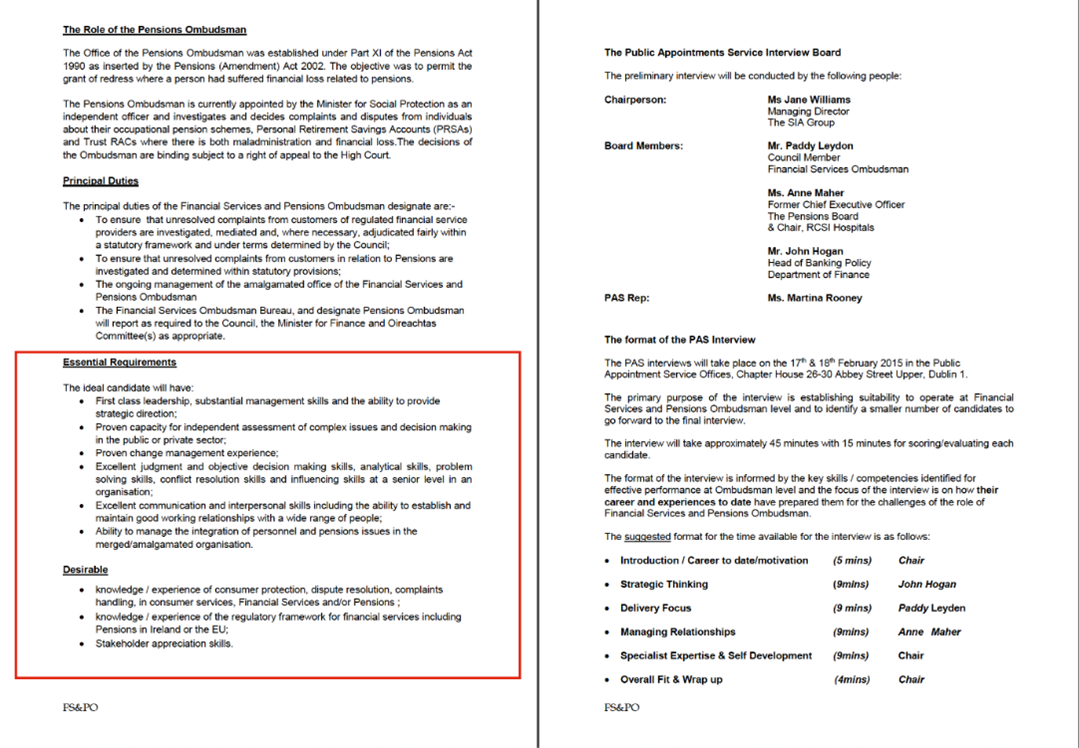

We now have access to another FOI request providing insights into the recruitment of Ger Deering to the office in 2015/16, at a point when the Financial Services Ombudsman FSO and Pension Ombudsman were still separate bodies.

A series of interviews were carried out with eight candidates on February 17-18, 2015 for the first round, and on February, 27, 2015 there were final interviews with the remaining three candidates, the “Board Members Guidelines” resembling a basic template for corporate hiring.

All of the interviewers had impressive CV’s and expertise, including Mr John Hogan, then Head of Banking Policy for the Department of Finance and recently appointed as Secretary General.

Revealingly, Hogan contributed to the “The Keane” Report on Residential Mortgage Arrears, which was criticised by Deputy Luke “Ming“ Flanaghan in 2011. The Report rules out the introduction of any scheme involving blanket debt forgiveness.

Notably, the majority of complaints received by the FSPO pertained to financial and banking issues. One would expect that any individual considered for that role – with powers to make legally binding decisions – would have extensive experience within the banking sector.

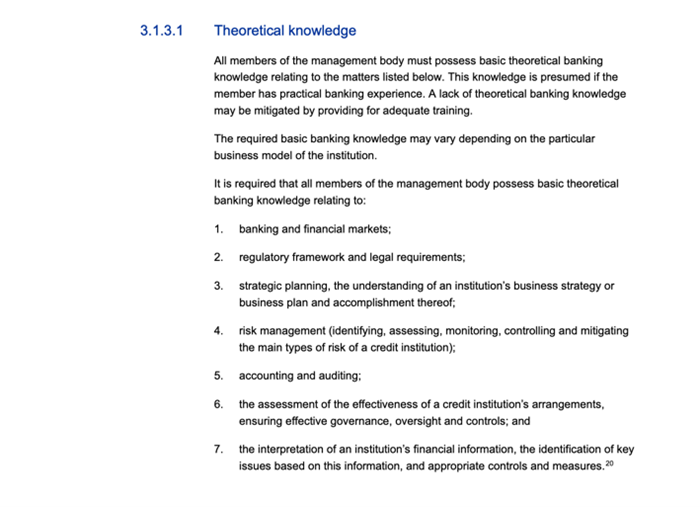

By analogy, if one looks at the skills required of managers and other positions with supervisory roles, employed in the banking and insurance sectors that are imposed by the EU Single Supervisory Mechanism, we find clear guidelines in regard to required banking knowledge or one can even look up the job description for an FSPO Case Manager in PTSB.

Yet in the advertised job description for The Financial and Pension Ombudsman we see theoretical banking or financial knowledge being “desirable” instead of “essential”, nor is there an examination process, beyond a standard interview.

This is not to question Ger Deering’s managerial skills, nor his ability to adapt and learn, but when the job requires him to lead an oversight body over the banking, insurance and pension industries, his work experience is not what one would expect for the appointment.

We know that the Office contains some banking expertise thanks to the qualifications of less senior staff, who have to deal with an enormous workload. But an appointment process for the top job focused on legal and managerial skills may perpetuate the current imbalance between the private and public sectors.

In the forthcoming recruitment process for a position such as the FSPO, it is surely in the interest of the Department of Finance to appoint a person with more than generic managerial skills, and for some form of competitive examination to occur. Otherwise, it will be difficult to convince an increasingly sceptical Irish public that the government is genuinely intent on levelling the playing field between ordinary citizens and “too big to fail” corporations.

Shared Responsibility

One might say that appointing an ex-banker to the position creates a dangerous revolving door between banks and regulators, and is itself a recipe for regulatory capture. That argument is right to a point, but does not take into account that the necessary banking expertise might be found outside the banking industry itself, such as in auditing and accountancy firms; or by casting the net internationally to guarantee a greater degree of separation between the regulator and the regulated, especially in a small country such as Ireland.

And, insofar as it is important to have sound legal advice, it is important that this is not set out in such a way as to intimidate complainants, and that the Office receives the same level of financial consultancy as the banks themselves.

When we talk about consumer protection in the financial industry, we are really talking about the level field that the government promises, in relation to an industry administering one of the most powerful means of control, which is the complex socio-psychological phenomenon of debt.

While some are celebrating that ‘The Boom is Back’, a significant proportion of the population is still struggling to overcome the effects that the previous boom and subsequent financial collapse actually brought; and, as in the period of austerity, the burden of bad choices is still carried almost exclusively by the most vulnerable and least resourced.