As a UCD undergraduate I recall Professor Tom Bartlett likening Irish history to a pint of Guinness, ‘with black representing ownership of the land, and the white froth everything else, including all the political movements.’

Old habits die hard. The issue of property remains a paramount concern. By the year 2004 Ireland’s rate of private home ownership was the highest in the OECD at approximately 82%, a proportion that only declined, to 69% in 2014, after the Crash from 2008, precipitated by reckless lending, often to ‘sub-prime’ borrowers. This reflects the ongoing effect of a global financialisation of property as a speculative asset from the 1980s, leading to the exclusion of a substantial proportion of a younger generation from home ownership across most of Europe, North America and beyond.

Ireland’s housing crisis is a special case however. In order to understand its long term causes – Dublin is now the most expensive city in the euro area primarily due to staggeringly high rents – it is necessary to explore an historic relationship with land, arising out of a colonial experience. This has brought an economy where the land grabber reigns ascendant.

Photo ©Daniele Idini

Urbanisation

A nation derives characteristics from its relationship to the land it inhabits. Over recent centuries, in Ireland, as elsewhere, mass urbanisation, disproportionately directed at Dublin, has occurred, but we have built our cities on historical patterns of land ownership.

There are two defining, and intertwining, legacies of the Irish relationship to property that have seeped into the broader culture. The first is the impact of English colonisation, in particular the Plantations, beginning in the sixteenth century, and the subsequent partial de-colonisation through the Land Acts of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The second is the dominance of pastoral, livestock agriculture, particularly since the late nineteenth century under a system of individual land ownership – as opposed to treating property as a collective patrimony under Brehon Law in Gaelic Ireland.

Photo ©Daniele Idini

It is incorrect to assume cattle-farming has always been the dominant form of agriculture in Ireland. Since the first human settlements emphasis has swung back and forth between tillage and pasture; and in earlier centuries cattle were kept for domestic milk production rather than to produce a (beef) commodity for export.

Moreover, the introduction of the wonder crop of the potato from the seventeenth century created a novel opportunity for subsistence on small holdings, bringing marginal land into cultivation for the first time. Although, ominously, according to John Reader in The Untold Story of the Potato (2008), ‘the innocent potato has facilitated exploitation wherever it has been introduced and cultivated.’ It acted like cheap credit in generating a ready source of subsistence on small parcels of land, but the potato cannot be preserved for a long period like grain so cannot easily be traded, thereby impeding development.

Over time, the impact of Irish agriculture, especially extensive grazing, on Ireland’s nature has been profound. According to Frank Mitchell in Reading the Irish Landscape (1997): ‘from about five thousand years ago when the first tree-felling axes made woodland clearance possible man’s hands have borne down ever more heavily on the Irish landscape.’ This left a mere twelve per cent woodland coverage by the 1400s, before the most intense period of colonisation at the end of the eighteenth century when a poet lamented:

Cad a dhéanfaimid feasta gan adhmad? / Tá deireadh na gcoillte ar lár;

Now what will we do for timber, / With the last of the woods laid low?

Photo ©Daniele Idini

Today among EU countries only Luxembourg has lower coverage, and much of our woodland is in the form of sitka spruce plantations that further degrade the land, while offering little scope for biodiversity.

The sixteenth and seventeenth century Plantations trapped an overwhelmingly Catholic peasantry, denuded of a departed upper stratum of Gaelic society, in a Malthusian grip that culminated in the Famine.

Portrait of Seán Ó Faoláin by Howard Coster, 1930’s

Describing the acquisition of annual leases by small farmers, who had previously held land in common under the Brehon Law system, Seán O’Faoláin wrote in The Irish (1947): ‘The thirst for security is, above all things, the great obsession of the peasant mind. And, in a long view, a deceptive obsession.’ Security of tenure under the new dispensation was illusory, as land became an asset to be bought and sold, rather than a collective patrimony.

Trade conditions shifted in the nineteenth century. The raising of cattle, often exported ‘on the hoof’ to England for eventual slaughter, began to enjoy a comparative advantage over tillage as the British discovered cheaper sources of grain after Napoleon’s blockade ended with the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Henceforth, the cheap labour of the Irish peasantry – a substantial proportion unconnected to the market economy – were an anachronism to the British administration in Ireland.

The Famine (1845-1851) was, according to Charles Trevelyan the architect of Britain’s response ‘a direct stroke of an all-wise and all-merciful Providence’, which laid bare ‘the deep and inveterate root of social evil.’ Anticipating the Shock Doctrine, the Famine, he declared, was:

the sharp but effectual remedy by which the cure is likely to be effected… God grant that the generation to which this great opportunity has been offered may rightly perform its part…

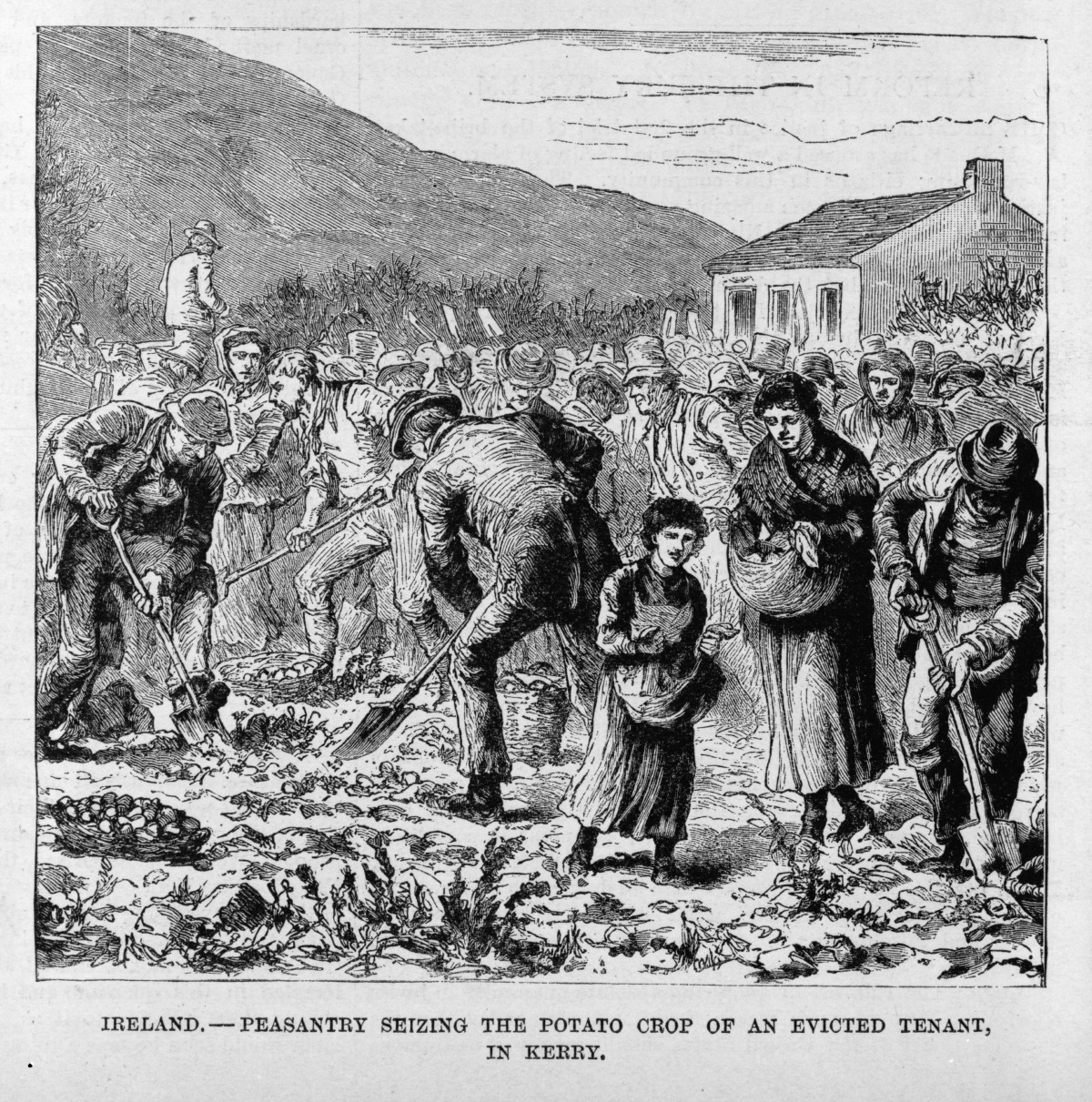

Wood engraving, 1886. cc Library of Congress

Strong Farmers

The Famine was a catalyst for change that brought about the dominance of cattle agriculture, increasingly under the native so-called Strong Farmer. The key point about this mode of production was (and is) that profitability depends on a low labour input. It made no sense for numerous sons and daughters to remain on the land, and so the tsunami of emigration that formed during the Famine gave way to steady migratory waves. Over the long term this brought precipitous population decline throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century.

As Joseph Connolly put it in his Labour in Irish History (1910): ‘Where a hundred families had reaped a sustenance from their small farms, or by hiring out their labour to the owners of large farms, a dozen shepherds now occupied their places.’

This process should not, however, be attributed solely to remote authorities in Westminster working on behalf of absentee landlords, as is commonly assumed. Significant gains were made by Catholic Irish farmers holding farms above twenty acres. As Kerby A. Miller wrote in The Atlas of the Great Famine (2012): ‘an unknown but surely very large proportion of Famine sufferers were not evicted by Protestant landlords but by Catholic strong and middling farmers, who drove off their subtenants and cottiers, and dismissed their labourers and servants, both to save themselves from ruin and to consolidate their own properties.’

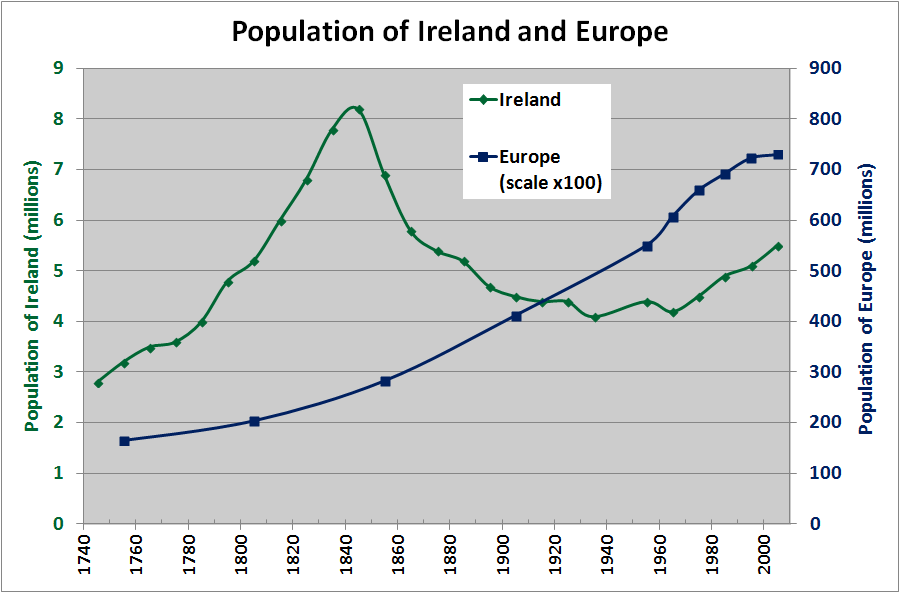

As Ireland did not witness an Industrial Revolution, except in the North-East corner, this shift from tillage to pasture led to unprecedented population decline. Ireland is perhaps the only substantial country in the world with a lower population now than in the 1840s, when the population stood at almost nine million. In the same period the global population has increased seven-fold.

National Independence

The struggle for Irish independence was taken up by Strong Farmers, a comprador class selling their primary products on the Imperial market, who emerged with enlarged holdings after land clearances, to become the dominant faction of an overwhelming Catholic ‘nation’ at the end of the nineteenth century. Through a succession of legislative measures, culminating in Wyndham’s Land Act of 1903, the British administration sought, but failed, to ‘kill Home Rule with kindness’, allowing tenants to obtain freeholds over much of the country.

This allowed their sons to set about dominating local government, the Irish Parliamentary Party, and later Sinn Féin. This cohort entered the professions, established a National University in 1908 (Maynooth University had also been established in 1796) and eventually won an independent state in 1922, wedded to an individualist and competitive approach to land, in contrast to collaborative arrangements typically associated with tillage, including the Clachan settlements of pre-Famine Ireland. The first Minister for Agriculture, Patrick Hogan (in office from 1922-32), was a cattle farmer, and duly aligned the national interest with the economic fortunes of his ‘grazier’ class.

After independence in 1922, pastoral Strong Farmers continued to sell mostly cattle onto the Imperial market, notwithstanding the aspiration of idealists like Robert Barton, the first Director of Agriculture (1919-21), for a reversion to more labour-intensive tillage for domestic consumption; except, that is, for a period in the 1930s and 1940s when national survival demanded increased focus on growing subsistence crops.

Photo ©Daniele Idini

Individualist Outlook

The outlook of the peasant-pastoralist has informed our laws and values since the inception of the State, spreading from rural Ireland into an increasingly urbanized society. As O’Faoláin put it:

we have seen the common folk of Ireland rise like a beanstalk out of the Revolution of 1922 and, for a generation, their behaviour was often very unpleasant to watch.

The arrival of mechanisation in the Green Revolution after World War II put tillage at a further disadvantage as, despite enjoying among the highest global yields, high levels of precipitation and humidity make Irish-grown cereals, apart from oats, unsuited to mechanised harvesting. The traditional method of ‘bindering’ – drying the harvest over months in stacks – became uncompetitive due to high labour inputs, and so the population drain form rural Ireland continued.

Moreover, since the 1970s price supports from the European Community’s Common Agricultural Policy have reduced flexibility and dynamism in land use, by inflating values as farmers were guaranteed payments, even on poor land, without adequately addressing the associated population drain.

Legal Protections

As the sons and daughters of peasant-proprietors migrated to cities, especially Dublin, Ireland’s politics of clientelism embodied in the two main political parties took hold. An urban population with roots in raising livestock prizes land as an asset from which profit is derived, as opposed to a situation where crops are cultivated for the family table and traded within the community.

An inherited skill in deal-making was readily applied to urban development, which is also reflected in strict judicial interpretations of private property, allowing enterprising developers to make a killing. Thus, State institutions have favoured the landed interest over the property-less, in a troubling reminder of a bygone era.

In 1973 the Kenny Report recommended that land around the hinterland of Dublin should be compulsorily purchased by local authorities for 25% more than its agricultural value. According to Frank McDonald, the former Environment Correspondent of the Irish Times, Dr Garret FitzGerald, a member of the Fine Gael-Labour Coalition government that received the report could not remember why it wasn’t acted upon. ‘It just slid off the agenda’ he said, and no subsequent government acted upon it. McDonald said that ‘Ostensibly, the reason for this was that Kenny – a constitutional lawyer himself – had proposed something that would be unconstitutional. But no attempt was made to test this in the courts.’

That was until Part V of the Planning Act 2000. This was referred to the Supreme Court which held that the acquisition of land for social and affordable housing did not offend against the Constitution. Unfortunately, however, that provision did little to ameliorate the housing crisis during the Celtic Tiger as developers evaded responsibility by paying over sums to local authorities, and successive Ministers watered down the provisions.

The reluctance of politicians to implement the Kenny Report reflected a genuine fear that any such provision would fall foul of the Court, which has tended to vindicate a constitutional right to property under Articles 40.3.2 and 43.1.2 over competing interests of renters to security of tenure or a controlled rent.

Thus, in 1981 the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional attempts to introduce rent controls under The Housing (Private Rented Dwellings) Bill, while the wide scope of Article 45 has been given little attention.

This reflects a sectional bias as the common good (to which all constitutional rights are subject) should allocate a reasonable prospect of basic accommodation to all permanent residents.

Photo ©Daniele Idini

Unenumerated Rights

The idea of an ‘unenumerated’ Constitutional right – in that instance a right to bodily Integrity – was first identified by the same Justice Kenny in his landmark High Court judgment of Ryan v Attorney General (1965). A right to adequate shelter may also be unenumerated. For instance, Kenny’s seminal Ryan judgment cited the papal encyclical Pacem in Terris (1963) which states that: ‘every man has the right to bodily integrity, and to the means which are necessary and suitable for the proper development of life. These means are primarily food, clothing, shelter, rest, medical care and finally the necessary services.’ Yet the Court has avoided vindicating a basic human right to adequate shelter.

Now, underpinned by legal and political deference to the property interest, we see huge swathes of land and buildings that have been left fallow in urban areas: a 2016 report in The Dublin Inquirer identified at least 389 derelict sites. We are unaccustomed to urban density, or community developments, except as a sign of poverty – with the 1930s schemes of Herbert Simms a rare and inspiring exception. Strict demarcation between properties, and a lack of community spaces, may be interpreted as a legacy of extensive cattle-rearing for the imperial market.

Furthermore, the sons and daughters of nineteenth century pastoralists, accustomed to low-density living with few neighbours on the horizon, sought distance from their neighbours, and the assurance of owning a motor car. This accounts for the sprawl, and prevalence of needless boundary walls, in Irish suburbia; as well as a preference for one-off housing.

The commercial culture can also be linked to the pastoral outlook. It is revealing that few successful Irish businesspeople have been technological innovators. Rather, success has been built on buying low and selling high, just as a cattle farmer buys a calf and seeks to sell him at a higher price – the entrepreneur Tony Ryan was quoted as saying ‘you make your profit the day you buy.’ Thus developers often purchase land at a low price and sit on this until financial conditions improve. The Irish dream is built on living off the fat of the land, creating conditions to the liking of the vulture and cuckoo funds our government now accommodates.

Photo ©Daniele Idini

Historic Failings

No Western economy experienced growth, at least in the period 1995-2007, comparable to that of the Celtic Tiger, but this was achieved, at least in part, through the availability of cheap, and ultimately ruinous, loans, by unscrupulous bankers. But like the wonder crop of the potato, these loans generated ultimately ruinous growth.

Failure of both property and potatoes emanated from America. In the case of the Famine it was the dreaded blight, phytophthora infestans, which first blackened the leaves and then reduced the crop to inedible mush. The pin that burst the Irish property bubble, a large boil on a global wart, was marked with another American sign, that of the ruinous Lehman Brothers. Both the potato blight and subprime mortgages afflicted other countries, but perhaps nowhere as severely as Ireland.

The austerity that followed may be likened to the extreme Shock Doctrine practised by Charles Trevelyan, while the feeding frenzy that occurred through NAMA recalls the land-grabbing in the wake of the Famine.

In order to address Ireland’s Housing Crisis we must face up to the sins of our fathers, including an enduring bias in favour of strict individual ownership preached by the two main political parties in government, as well as the judiciary.

A version of this article appeared in Village Magazine.

Title Image: House in proximity to Dog’s Bay, Connemara. ©Daniele Idini