Paul O’Brien’s biography, Sean O’Casey, Political Activist and Writer (Cork University Press) is a timely re-assessment of an often controversial, figure whose place in the literary canon is, O’Brien argues, is insufficiently acclaimed.

It coincides with the hundredth anniversary of Druid’s production of O’Casey’s Dublin Trilogy: ‘The Plough and The Stars’, ‘Juno and the Paycock’ and ‘The Shadow of a Gunman’ which opened recently at the Galway Arts’ Festival and will tour Belfast before coming to The Abbey in September. But, with the publication of Timothy Murtagh’s new book Spectral Mansions on how the once graciously lofty Henrietta Street turned into tenements adding to the mountain of scholarship about Dublin tenement life, O’Casey’s plays, are, on that basis alone, destined for immortality.

As enduring testimonies of the unflinching reality of Dublin tenement life, no playwright evokes and captures the life of Dublin’s tenements as does O’Casey and that is the central theme of this tour-de-force of scholarship.

Sean O’Casey was born in 1880 into a lower middle class Protestant family – the youngest of eight children – and was raised in Lower Dorset Street, where the family enjoyed a relatively comfortable lower middle-class life until after his father’s death in 1886. His father had been employed in the Irish Church Mission and his older brothers attended the Central Model School in Marlboro Street for which a small fee was required.

In reduced circumstances after his father death, and when O’Casey was nine, the family moved to the East Wall – a hot bed of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA) and the ITGWU. His entire oeuvre dramatizes with unflinching realism and lack of sentimentality the grim realities of tenement life in Dublin, infusing his characters with compassion and humanity.

By the 1930s, Dublin’s tenements were among the worst slums in Europe with a very high mortality rate, rampant prostitution and disease reflected in ‘The Plough and The Stars’ in the character Mossler Gogan dying of TB and the prostitute Rosie Redmond. Indeed, according to O’Brien ‘[i]n 1914 it was believed that tenement dwellers had a better chance of survival on the Western Front than in the diseased-ridden hovels of Dublin.’ Thus, O’Casey became ‘a life-long activist for the preferment of dwellers of tenements, reflecting their lives with scrupulous realism and compassion, their humanity always shone through as did their heroism and their promise.’

Henrietta Street, Dublin.

Excruciating Detail

Paul O’Brien biography on O’Casey charts with intense and excruciating detail the development of O’Casey’s politics and how those politics fused and informed his writings, especially his dramatic works. In that sense, O’Brien’s book takes a thematic rather than a chronological approach to O’Casey’s life.

While O’Casey’s older brothers attended the model school in Marlboro Street, Sean, a delicate child was largely home schooled, self-taught and, for a time, taught by his older sister, a teacher. Later, O’Casey was immersed in all the key political movements of his time, the ICA, the Gaelic League, the GAA and was a big admirer of, and influenced by, Parnell.

He mastered Irish, hence the change in his birth name from John to Sean and he studied the Classics. From early in his life, he was interested in the national movement but it was the emergent labour movement, gaining momentum under his life-long hero, James Larkin that really gripped him and the entire dynamic of his subsequent political and writing life revolved around his failure to find a synthesis between Irish Republicanism and the international struggle of the working classes.

In other words he never could accommodated the ‘green’ of Nationalism with the ‘red’ of Labour and this unreconciled tension remained the central dilemma of his entire life and, in exploring it in minute intensity, Paul O’Brien uncloaks it as both the triumph and tragedy of O’Casey’s life too. While Paul O’Brien clearly admires his subject, he is candid about the unjustified personal animosity of O’Casey towards James Connolly. O’Brien does not shirk from revealing any of O’Casey’s flaws in judgement and personality, while never losing sight of his overall genius.

Imbrications between the cause of the working classes in Dublin and accelerating nationalism were unavoidable after Parnell and were so fused as to often be indistinguishable; the overlaps were everywhere, not least in the Irish Citizen Army (ICS) of which O’Casey was a member until he finally severed all ties in 1914. He also derided the Irish Volunteers which emerged in the South, in parallel with the formation of the Ulster Volunteers in response to the Home Rule Bill of 1912.

James Larkin.

James Larkin

James Larkin arrived in Dublin in 1907 and inspired O’Casey to use ‘words as weapons against exploiters of the Dublin poor.’ O’Casey first gave vent to his rage in Larkin’s paper The Irish Worker. Later, in his biographies, O’Casey lacerated the corruption of Dublin Corporation.

From an early age, O’Casey’s love of literature was manifest. The hope that Irish life would be transformed died with the early and tragic death of Parnell in October 1891. In the aftermath, the prospect of peaceful evolution along the lines of Dominion Status enjoyed by Canada and Australia receded.

O’Casey saw Larkin as the greatest Irishman since Parnell. ‘The Plough and The Stars’, O’Casey’s most controversial play premiered in the Abbey in 1926 and was well received on its first night. But on the second night, a combination of 1916 widows and Republicans escalated into full blown riots with added moral consternation at the prostitute Rosie Redmond awaiting clients and the un-named figure in the window, identifiably Patrick Pearse extolling the sanctity of bloodshed.

The first two acts of the play are set in 1915 looking forward to the liberation of Ireland, but the second two acts are set during the 1916 Easter Rising.

In the evolution of his political ideals, O’Casey had a number of influences aside from Parnell; the writings of James Fintan Lalor (1809-1849) and John Mitchell (1915-1875) influence him. The 1913 Lockout in Dublin was a watershed moment for O’Casey.

Parnell had provided a vision for Ireland with no conflict between the Protestant religion and the principles of freedom which had a democratic and libertarian pulse, rooted in Constitutionalism. But contemporary conditions would sweep O’Casey away from family and Protestant traditions.

A Dublin Tram conductor and an Abbey actor introduced him to rawer politics. This, combined with the ICA and the ITGWU provided different currents on O’Casey’s development. In terms of his literary work, Dion Boucicault remained a strong influence in how he used songs and comedy to lighten the tragedy of his own writings. (O’Casey wrote many, long forgotten, ballads) While Boucicault’s plays are traditional melodramas there is also a ‘political ambivalence that challenges the stereotypical image of the stage Irishman; ‘Arrah-Na-Pogue’ and ‘Peep O’Day’ are about the 1798 rebellion. Boucicault created a more trustworthy image of the Irish, replacing the racial stereotype in English literature which was finally killed off by George Bernard Shaw in Larry Doyle in ‘John Bull’s Other Ireland.’ O’Casey draws on the techniques of Boucicault, Shakespeare’s history plays and on Shaw to create a unique synthesis of his own. O’Brien argues that O’Casey’s conclusions are ‘open-ended.’

Dion Boucicault.

The Boer War

Defining nationhood was intensified by anti-British sentiments after the Boer War, the centenary celebrations of 1798 and the Jubilee celebrations in 1889.

O’Casey imbibed the sentiments of the Gaelic League like many other Protestants. The plough and the stars was the flag of the Irish Citizen Army, and O’Brien identifies O’Casey’s problem was to ‘hitch the plough to the stars.’

He joined the Gaelic league in 1901 and took up hurling. He became an apprentice bricklayer and worked for a number of years on the Great Northern Railway Line. In 1908, he became secretary to the Drumcondra branch of the Gaelic League and spent ten years promoting Irish language and culture but increasingly he saw the chief enemy as the crushing force of capitalism, and, as he matured, he rejected romantic nationalism.

James Connolly was able to unite nationalism and socialism, but O’Casey could never fuse them into a cohesive theory remaining haunted by the voice of the urban poor. O’Casey resigned from the IRB in 1913 when they refused to take the workers’ side in the Great Lockout.

He ditched the Gaelic League for Larkin and the momentum behind Larkin radical labour movement became the driving force for his plays. This transition is reflected in his earlier plays The Harvest Festival, The Stars Turn Red and Red Roses For Me which deal with the labour history of the 1913-1914 Lockout. After the failure of the Great Lockout O’Casey’s views were crystallised into the view that the ‘struggle was not one of English Imperialism versus Irish Republicanism but between international capitalism and the workers of the world’ and this is reflected uncompromisingly in his plays.

In 1914, Larkin went to America to organise the international workers of the world and was jailed for criminal anarchy. The Ulster Covenant saw 4,000 Ulster volunteers sign up and the respondent Irish Volunteers were despised by O’Casey who saw it as dominated by ‘overfed aristocrats’.

He clashed with Tom Kettle and Pearse and wrongly accused them of not supporting workers. In 1914, along with Larkin, he drafted a new constitution for the ICA but the problems of aligning the red of Labour with the green of nationalism persisted for O’Casey.

Countess Constance Markiewicz.

‘a spluttering Catherine Wheel of irresponsibility.’

When Connolly expressed his vision for the re-conquest of Ireland in a pamphlet in 1915, O’Casey saw it as Connolly lowering the red flag in favour of the green and made a sudden and final split with the ICA. The Countess Markievicz joined the Irish Volunteers and the ICA.

O’Casey was intensely hostile to her ‘hauteur’: ‘she whirled into a meeting and whirled out again a spluttering Catherine Wheel of irresponsibility.’ His motion, however, to expel her from the ICA failed. According to O’Brien ‘he rushed headlong into one dispute after another, damaging himself and alienating his friends.’

O’Casey published a book on the ICA in 1919 but, according to O’Brien it lacks balance and is saturated with vitriol and opinions. His core argument was that nationalism gained and labour lost as a result of the ICA’s involvement with 1916. ‘O’Casey was alone is seeing Irish history from a working-class perspective when, after 1916, The Labour movement was subsumed into the struggle for independence.’

When Connolly joined the Volunteers in 1916 it completed the fusion with the ICA. 220 members of the ICA rose on Easter Monday 1916, but 1,200 Irish Volunteers did. As O’Brien points out, Connolly had little choice but to fight on nationalist terms in 1916.

Connolly had grasped the importance of a united front where O’Casey failed. O’Casey never acknowledged Connolly’s attempts to unite Labour and Nationalism but in later years he did acknowledge Connolly’s standing in the Labour movement but ‘he never lost an opportunity to denigrate Connolly in favour of Larkin.’

O’Casey became ‘a disgruntled outside, a hurler on the ditch, shouting the odds as history passed him by.’ Many critics put O’Casey’s vitriol against 1916 in ‘The Plough and the Stars’ down to ‘survivor’s guilt.’ The summary execution of Francis Sheehy Skeffington, a socialist and passivist abhorred him. He felt successful revolution on nationalist terms only empowered the new Irish ruling classes – the very people who had reduced the Dublin poor to abject poverty.

O’Casey was in sympathy with the views of Ernie O’Malley who resented the legendary status that emerged in the aftermath of the 1916 martyrs as they were twisted and idealised by a new state to consolidate its position. O’Brien argues that ultimately O’Casey neither deified or vilified the 1916 heroes but rather projected the realities of the new Free State that emerged, and, in that, he saw it as advancing commerce over the plight of the poor.

In ‘The Plough and The Stars’ he ‘inverted the nationalist myth … and summoned his characters from the margins of history and placed them in the spotlight.’

‘The Shadow of a Gunman’ was influenced by Ernie O’Malley’s views in the character of Davoren, an opportunistic carpetbagger who capitalised in the new Free State which the play mocks. The rhetoric of romantic nationalism is ridiculed and critiqued.

In all of O’Casey’s plays his characters are overwhelmed by events outside of their control. Unlike ‘The Dublin Trilogy’ his plays ‘The Cooing of the Doves’ and ‘Kathleen Listens In’ supports the pro-treaty side. Kathleen also counters the glorification of dead heroes and martyrdom.

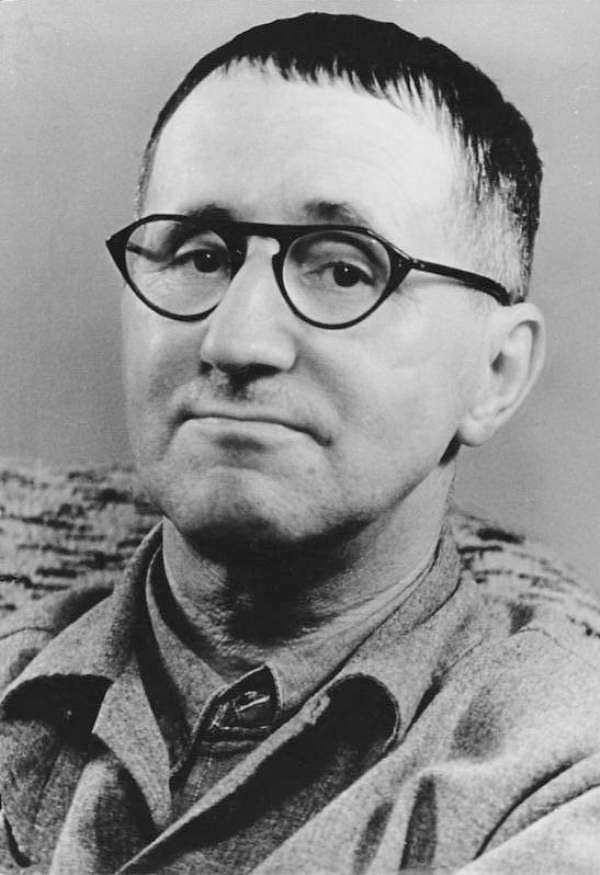

Bertolt Brecht.

Influenced by Brecht

‘Juno and the Paycock’ (Abbey 1924) fuses tragedy and comedy: Captain Boyle, a figure broken by poverty and drink is still a sympathetic character. The life of the tenements is always pitched against the life outside and many saw the play as a condemnation of all war.

Juno too has been seen as an attack on the Republican movement. The character Juno is Brecht’s Mother Courage of Dublin with her strength and humanity. O’Casey was influenced by Brecht, Ibsen and other experimental dramatist. In common with Shaw and Joyce, he despised the cult of Cathleen Ni Houlihan as symbol of Ireland. In a feminist twist, Juno does leave her abusive husband and goes off to make a new life with her unwed pregnant daughter.

O’Casey moved to London in 1926 to receive the Hawthornden prize and produce the London production of Juno. He met and fell in love with actress Eileen Carey and he married her and the couple moved to Devon where they went on to have three children.

Yeats refused to produce The Silver Tassie at the Abbey in 1928 causing an irrevocable breach between the Abbey and its most successful playwright. When Juno opened in London O’Casey was a minor celebrity and controversially hobnobbed with a succession of high society grandees, especially with Lord and Lady Londonderry, even spending a week at their residence, Mount Stewart, on the Ards Peninsula in 1934.

They were the direct descendants of Lord Castlereagh, ruthless executioner of the United Irishmen in 1798. He rubbed shoulders with figures as controversial as Oswald Mosely. On the other hand, his Communist activities led him to clashes with George Orwell who, in 1949 supplied O’Casey’s name as part of a secret list of about a hundred writers, artists and intellectuals who should not become ‘cheerleaders in Britian’s fight against communism’ to British intelligence (see issue 3, History Ireland, Autumn 1998).

O’Casey’s was unable to deal objectively with the Stalinist pogroms and took the Russian side against Hungary in the uprising of 1956. For all his human lapses, O’Casey emerges largely as mostly being on the right side of history and was an ardent supporter of Noel Browne. His later plays too were polemics against Nazism and Fascism. He was bitterly disappointed by the failures of his expressionist plays, ‘The Silver Tassie’ and ‘Within the Gates’.

Dublin, 1916.

An Exhaustive Feat

Paul O’Brien’s book, with some occasional unavoidable repetition is an exhaustive feat of research and scholarship that should become an indispensable handbook to all aficionados, practitioners, academics and teachers of Irish drama. In addition to existing scholarship, O’Brien opens a new window of insight into O’Casey’s passion, commitment and motivations while never eschewing his human flaws.

This is also an indispensable history of the development of the Irish labour and nationalist movements and their fraught and intricate interface in the aftermath of Parnell and into the early twentieth century; through The Easter Rising, The War of Independence, The Civil War and its aftermath.

As a writer, O’Casey developed his own unique style and never failed to move with the modernism of Ibsen, the Expressionism of Ernst Toller – the German anti-Nazi playwright – Brecht and Shaw who were early influences. He disliked pessimistic theatre but made an exception with Beckett. Paul O’Brien makes a compelling case that O’Casey’s expressionist and modernist plays are overlooked. His book certainly inspires a fresh look at O’Casey overall oeuvre.

With ‘The Dublin Trilogy’ currently enjoying a successful run as part of the decade of centenaries his place in the pantheon of Irish dramatists seems assured, and, as the history of Dublin tenement life continues to burgeon, his plays are set to endure as visceral, dramatic slices of that life. Perhaps the most astute accolade O’Brien accords O’Casey is to observe that; ‘he was one of the most sensual writers of his era’ where ‘sexual love is always presented as positive, joyful and life affirming’ and that was the common humanity that placed the characters of Dublin’s tenements on a par, as O’Brien suggests, with ‘Maud Gonne, the Countess and their aristocratic circle.’

Paul O’Brien richly deserves the accolade of O’Casey’s biographer, Dr Christopher Murray, Emeritus Professor of Drama at UCD who greeted, ‘An extraordinary achievement bringing O’Casey centre-stage again with supreme skill. Bravo!’

Sean O’Casey Political Activist and Writer by Paul O’Brien is published by Cork University Press in hardback at €49. It is 297 pages with a Foreword by Shivaun O’Casey. There are an additional 100 pages of notes, bibliography and index.

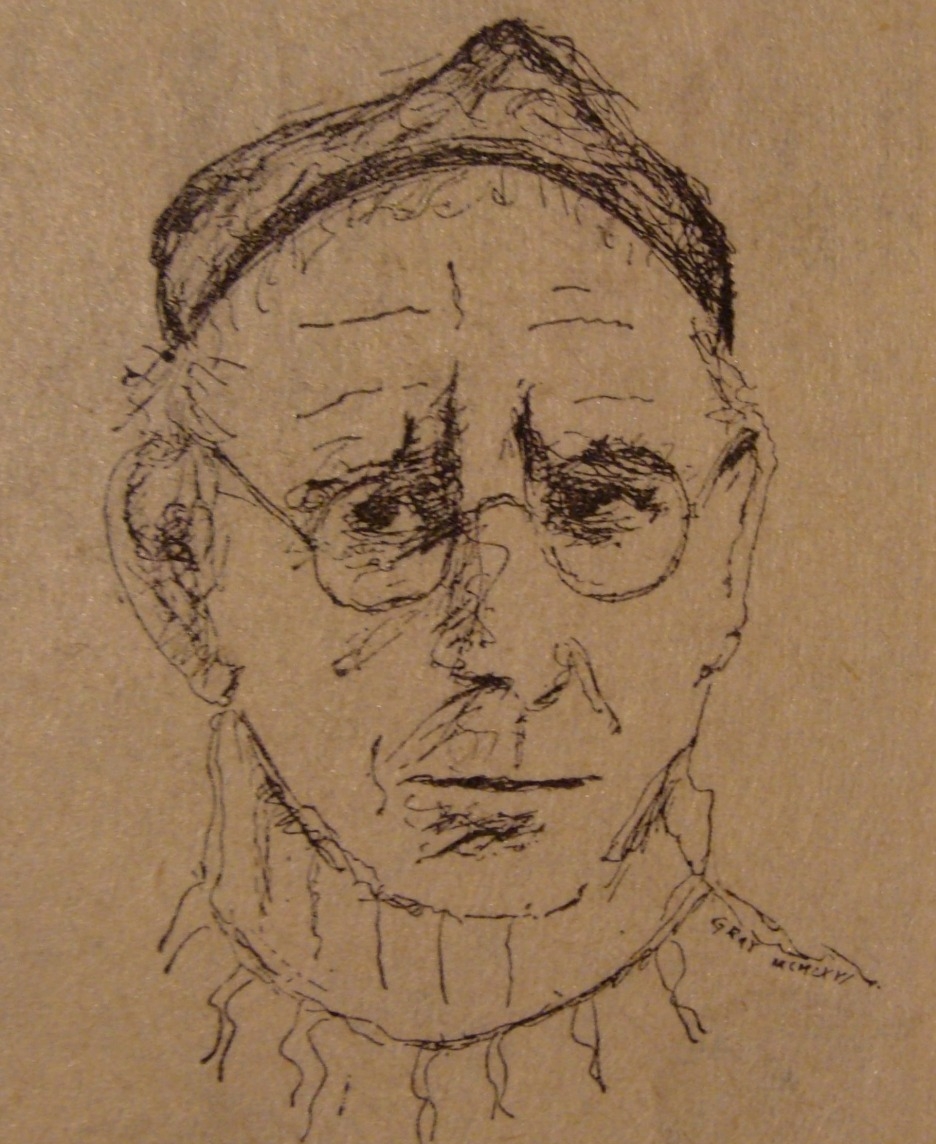

Feature Image: Study of Seán O’Casey by Dublin artist Reginald Gray, for The New York Times (1966)