He wants to work Monday nights but not Tuesday afternoons; she is available on Saturday evenings but not on Sunday mornings… Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises often find it challenging to recruit part-time workers, with abundant choices available to gig workers in different sectors, but the pandemic has vividly demonstrated the nature and depth of insecurity of this form of employment.

Gig economy workers can range from traditional independent contractors to freelancers and temporary employees, who work at different times during the week. A few examples of companies where gig is the norm include TaskRabbit and Lyft in the U.S.; Uber, Swiggy and Zomato in India; and DiDi, Ele.me and Meituan riders in China.

Some may use gig work to supplement the income they receive from a traditional job. In the U.S., research shows that at least one-third of the total workforce[1] relies on gig economy work as a primary source of income.

Trade Unions generally oppose gig work and have tended to be resistant to independent contractors[2]; for years state legislatures have sought to enforce employment law and regulations on companies operating in the gig environment.

Bearing Risk

The platter of risks that gig workers bear not only relate to labour inputs, but also capital investments, as continuing in work is dependent on circumstances beyond the control of the worker.

For example, Uber, DiDi or Ola drivers use their own money, or borrow it, to pay for their cars. Yet companies may ‘decommission’ drivers in the event of: (a) the company changing the amount it pays to drivers or; (b) the ride-hailing industry experiencing increased competition; or (c) if the company gets flooded with new Uber (or other ride-hailing companies) drivers, due to low barriers of entry; (d) a driver may receiving low satisfaction ratings from customers.

A decommissioned driver may then be burdened with debt, with no ready means of repayment. The platform providers ensure that their workers are not classified as employees in any form, and thereby owe no entitlements to workers.

This is despite the gig ‘employee’ paying for and providing a physical asset that the platform relies on to carry out its business. The objective of the platform providers is to ensure that gig workers are considered independent contractors, and not employees.[3] Contractors in the traditional economy, such as truck drivers, may also sometimes supply their own ‘tools’, but the gig economy differs in that the gig worker doesn’t accumulate any goodwill that can be sold-on or leveraged for financial gain. The goodwill accrues to the platform provider, leaving the worker with few options.

Conventional employers attract full-time talent by offering a stable work environment, a retirement plan, along with other ‘soft’ benefits such as a modern office space, free food and drink and other fringe benefits[4].

However, there is a rational for businesses to engage ‘non-employee’ freelancers to work with their internal teams. The most compelling reasons are: (i) flexibility, (ii) access to expertise, (iii) speed, and (iv) cost. Thus in a survey conducted by Deloitte in 2014, 51% of executives said they expected the use of contingent talent to increase over the next 3-5 years.[5]

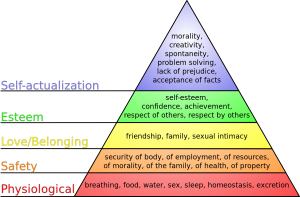

Temporary, irregular work ideally fits someone looking for extra money on the side, or a person who prefers an ad hoc schedule. However a large demographic among the middle class simply cannot afford instability, and are not getting fairly remunerated for their work. Gig work does not bring sufficient security for anyone planning a family, nor does it fulfil at least three of Maslow’s five Hierarchy of Needs (i.e. physiological, safety, social, esteem and self-actualisation) that many full-time positions come with.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

The insecurity is very real. Recently, the U.S. Department of Labour (DOL) established that many workers, depending on contractual specificities, in the gig economy should be considered contractors for the purpose of federal wage and hour regulations[6].

Just as gig work can increase one’s earnings to an unlimited extent, the opposite can also hold true, with pay rates varying dramatically, and with a fixed minimum wages rare. The ‘feast or famine’ style of income can, therefore, become increasingly stressful; fluctuation in earnings can make it difficult to save for the future. This is exacerbated by not having an entitlement to a retirement package or pension contribution. Then there is the formidable issue of no sick leave – if gig workers are unable to work, they simply cannot earn.

Along Comes COVID-19…

Once the pandemic struck, gig workers’ income plummeted to an unprecedent extent, and most of them were not on healthcare plans either. This has placed many gig workers in an even more precarious situation.

The ILO recently remarked that Covid-19 could lead to ‘the worst global crisis since World War II’. The pandemic is projected to remove 6.7 per cent of working hours globally, in the second quarter of 2020 – this is the equivalent to the annual salary of 195 million full-time workers: accounting for 8.1 per cent, equivalent to 5 million full-time workers in Arab States; 7.8 per cent, or 12 million full-time workers Europe; and 7.2 per cent, or 125 million full-time workers in Asia and the Pacific[7]. This will affect the motivation levels of gig workers too, particularly those who have recently moved into this form of employment from full-time paid work that had enjoyed associated health insurance and other benefits.

The retail, airline, and hospitality sectors have all witnessed significant layoffs. A couple of months ago some of the leading gig-economy companies responded by offering basic sick leave provisions and safety equipment, including hand sanitizer for drivers.

Importantly, U.S. ride-hailing companies like Uber and Lyft decided to pay workers’ income for fourteen days of work if they received a Covid-19 diagnosis and needed to self-isolate, [8] while providing disinfectant products to their workers[9]. Nonetheless, last week Uber announced a 14% reduction to its workforce, while Lyft is on the brink of cutting 17% of its staff[10].

Uber taxi in Moscow.

Whether it is Deliveroo in the U.K., or Meituan in China, or Zomato in India, the fragility of ride-hailing, food-delivery or furniture building work is increasingly apparent through extended lockdowns in many countries, with social distancing set to continue indefinitely. As gig workers are considered ‘freelancers’ and not ‘employees’, companies are excused from offering employment protections like guaranteed wages and sick pay, which is particularly crucial during this crisis as sick individuals should not feel obliged to go out to work.

Huge job losses are now expected across higher income countries. The sectors most at risk include accommodation and food services, manufacturing, retail, and business and administrative activities. There is a high risk that end-of-year global unemployment figure will significantly exceed the initial ILO projection of twenty-five million redundancies[11].

Essential Services

As gig workers are not ‘employees’, most of them are caught between choosing whether to remain at home, self-isolating to avoid potentially passing the virus onto others or remaining in ‘essential’ service work to support themselves and their families.

Those affected include medical workers who are taking significant risks to treat the sick. They are, however, generally low-paid grocery store workers, delivery workers, Amazon factory workers, street cleaners, and others, who have not knowingly entered their chosen occupations expecting elevated health risks, but have nonetheless had to work through the lockdown. Otherwise, if they don’t work in an ‘essential’ line of work during the COVID-19 crisis, they are in lockdown along with everyone else, and may not easily secure employment.

Responses to the U.K. Quarterly Labour Force Survey suggest that workers in manufacturing , sales and service, cleaners, among others are unsuitable for adjusting to remote work. While some countries have provided assistance to workers unable to perform tasks from home, there are certain categories of workers who tend to fall through the cracks of these programmes. Among these are zero-hour contract workers, and small or off-market, self-employed workers such as those who deliver food and clean homes.

To insure against a repeat of this crisis impacting on gig workers, we require policies to support businesses, employment and incomes including: provision of essential healthcare benefits, economic stimulus incentivising job creation, enhanced workers’ rights; and, equally importantly, mechanisms for dispute resolution between government, workers and employers. The right measures could make all the difference between the economic survival or collapse of not just individuals but the economy as a whole.

De Blasio Protests the Layoffs of 500 LICH Nurses and Health Care Worker.

‘Chaos is a ladder’

It should be acknowledged that the crisis has also created opportunities for both the companies reliant on flexible employment and even the workers themselves. For example, it has led to partnerships in India between governments and private enterprise including Ola, Flipkart, Swiggy, Urban Company and Uber. This is playing a crucial role in containing Covid-19, according to a report published by the Ola Mobility Institute.

Additional examples include Uber’s announcement in early April of two new Business-to-Business (BTB) partnership arrangements in India. Firstly, with UberMedic, a 24-7 service that works with health care authorities. It provides transport for front-line health care providers to and from their homes and medical facilities. Secondly, BigBasket driver are assisting with last-mile delivery of everyday essential items in four cities.

Notably also, Uber’s main competitor, Ola Cabs agreed to provide five hundred vehicles to the Karnataka government to transport doctors and other Covid-19-related activities.

Also Flipkart, which still competes with Amazon in India, is currently in talks with cab aggregators and the Indian Railways to ensure smooth and hassle-free movement of essential products from vendors to customers. One of the objectives is to offer incentives to supply chain and delivery executives.

These sorts of collaboration allow governments to recognise the potential of gig workers in this crisis, and have produced two non-fiscal strategies; first, by actively engaging the technological capability of the gig platforms and their logistical networks (a hands-on approach); and secondly, passively facilitating their operations through legal protection (a hands-off approach).

The agility of businesses reliant on gig workers brings fewer staffing challenges. This flexibility is certainly of arguable advantage to workers, but at least it may be keeping a small percentage of gig workers in employment that might not otherwise exist.

Also, some gig work employers are sending staff for certification courses run by the likes of Apollo Hospitals in India. This learn how to stay safe and vigilant while delivering goods and services to customers.

In India, many, if not most, gig workers are also economic migrants, and a large proportion returned to their hometowns following the nationwide lockdown. Organisations are now unsure about the extent to which this trend will be reversed once restrictions are lifted.

Analytics on the many impacts of Covid-19 remain thin, apart from some well-researched and presented data available from John Hopkins. Nevertheless, it is increasingly clear that low-income workers have an elevated risk of contracting the virus, and thus the income support system currently in place will leave some low-income workers exposed if they feel compelled to go back to work. Greater protection of their income should be prioritized around the world, particularly in countries like India and the U.S. where gig work is slowly being formalised.

Research into the motivation levels of gig workers in mainland China demonstrates[12] that gig employers generally prefer to wield ‘sticks’ than offer ‘carrots’ to employees, leading to a precarious standard of living.

So far a few progressive steps have been taken in India, and a few more in the U.S., in companies such as Google, Facebook and Uber, who are coming around to recognise their contingent workers as ‘employees’.

At least this crisis creates the space to re-evaluate the operation of the gig economy, especially as we now recognise how ‘essential’ certain forms of work are. We can effectively rebalance our regulations and reward-systems, safeguarding the interest of gig workers, and creating a brighter future for the gig economy.

[1] Habans, R. (2017). The Gig Economy in Illinois An Exploratory Analysis of Independent Contracting, School of Labor and Employment Relations Labor Education Program

[2] Sparkman, D. (2019) The Gig Economy Poses New Safety Threats and Liabilities, EHS Today

[3] Jelani, V. (2016). In a ‘’Gig” Economy, Workers Taking on More Risk, Harvard University

[4] Alan Kohll (2019) How Your Office Space Impacts Employee Well-Being, Forbes

[5] Schwartz, J., Bohdal-Spiegelhoff, U., Gretczko, M., and Sloan, N. (2016). The gig economy: Distraction or disruption?, Deloitte

[6] Pasternak, D. (2019) U.S. Department of Labor Says “Gig Economy” Workers Are Independent Contractors, Not Employees (US), Employment Law Worldview

[7] ILO (2019) ILO: COVID-19 causes devastating losses in working hours and employment, COVID-19: Stimulating the economy and employment, International Labour Organization

[8] Pandemic Erodes Gig Economy Work, The New York Times, 2020

[9] Higgins, T. and Olson, P (2020) Uber, Lyft Cut Costs as Fewer People Take Rides Amid Coronavirus Pandemic, The Wall Street Journal

[10] Mukhopadhyay, B. and Chatwin, C. (2020). ‘Your driver is DiDi and minutes away from your pick-up point’: A Thematic case of DiDi and worker motivation in the gig economy of China. International Journal of Development and Emerging Economies, 8 (1), 1-17

[11] ILO, 2019.

[12] Mukhopadhyay and Chatwin, 2020.