Leo Varadkar dismisses his father Ashok’s claim to be a socialist, which came in an interview after his son became Taoiseach. According to Leo he does not really know what the term means:

You’ve probably seen stuff where he describes himself as a socialist but that’s total rubbish .. It’s not that he believes in high taxes or generous welfare, quite the contrary … Nor the nationalisation of the means of distribution of wealth or any of those sort of things (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.24).

It is not simply that Ashok Varadkar has misrepresented his real position, but that socialism is to be rubbished. As he put it recently in the Dáil, ‘What the Socialists want … is to divide society into some people who pay for everything and qualify for nothing …’

As a politician Leo has long represented those people who “pay for everything”, only to be preyed on by ‘parasitic’ socialists. It is a neat inversion of the Marxist argument that capitalism exploits workers, which has been used by conservatives in the United States with enduring success.

The Fine Gael party has traveled some distance from the days of former Taoiseach John A. Costello, who urged in 1969: ‘to put upon your banners the Just Society, that Fine Gale is not a Tory party’ (McCullagh,, 2010, p.398). Under Enda Kenny Tory strategists were brought in as advisors, and Varadkar now firmly positions the party in the centre-right of Irish politics.

I – The Young Turk

Trenchant criticism of Fine Gael’s social democratic legacy helped Leo Varadkar make his name within the party. In a notorious speech in 2007, which he retrospectively considers ‘terrible, crass and disrespectful’, he described the beleaguered Fianna Fáil Taoiseach Brian Cowen as ‘a Garret FitzGerald’, who had ‘trebled the national debt and effectively destroyed the country (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.88)’.

Garret FitzGerald was the leader of Fine Gael between 1977 and 1987, a two-term Taoiseach whose last administration was marked by soaring national debt, in part due to his reluctance to impose swingeing cuts, and also because of the presence within his coalition of the Labour Party, and opposition to austerity measures from the opposition Fianna Fáil, which changed its tune after winning the 1987 election.

Away with the old – former Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald.

FitzGerald was identified with the Keynesian economic policy of using government spending to stimulate economic activity. This approach goes back to John A. Costello’s First Inter-Party Government, 1948-51, when balanced budgets were abandoned and a capital budget first introduced. There was, however, always a conservative wing within the party aligned with the legacy of the two Cosgrave (father and son, W.T. and Liam) administrations of 1922-32 and 1974-77, and subsequently influenced by Milton Friedman’s Monetarist approach, underpinning Thatcherism.

MEP Brian Hayes remains an apologist for Varadkar’s speech: ‘There was a large part of Leo, me as well, who resents how the Garret FitzGerald government didn’t do the things they said they’d do to fix the economy. There were a lot of people in Fine Gael who were very disappointed [with the FitzGerald government]and he was trying to articulate that (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.87)’.

From the outset Varadkar had cannily identified that cleavage within Fine Gael. This is clear from one of his early missives to the Irish Times, written in the wake of the debacle of Michael Noonan’s loss to Bertie Aherne’s Fianna Fáil in the 2002 general election. He described an ‘internal conflict between its conservative Christian democrat base (which it is set on deserting) and its liberal, social democratic base from the Fitzgerald era (which deserted it some time ago) (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.46).’

In Varadkar’s view, the only strategic option was to appeal to that conservative, Christian Democratic base, and dispense with social-democratism altogether. This is consistent with rubbishing his father’s socialism today, but actually misrepresents the Christian basis of Fine Gael’s social-democratism, particularly that of John A. Costello’s son Declan Costello, the author of the Just Society.

For Varadkar Christian Democratism was synonymous with right-wing conservative politics, which was evident in his thinking from the outset. Initial Progressive Democrat inclinations gave way to respect for the leadership qualities of John Bruton. Membership of Young Fine Gael followed, while studying medicine in Trinity College.

This brought a Washington Ireland Programme for Service and Leadership internship in 2000, under Republican Congressman Peter King. The New York representative’s politics were centrist in American terms – where socialism is still a dirty word – but included an enduring commitment to state infrastructure, such as rail, while maintaining a conservative attitudes to same-sex marriage and abortion.

Ironically, given his current identification with liberal causes such as marriage equality, and the repeal of the Eighth Amendment, Leo appears to have initially drawn from the same conservative playbook. In 2010 he argued in relation to abortion services that ‘it isn’t the child’s fault that they’re the child of rape’; while on the question of marriage equality he once argued: ‘Every child has the right to a mother and father and, as much as is possible, the state should vindicate the right’. He even courted Ronan Mullen for a time, inviting him to address a constituency meeting in 2007 on the issue of civil partnerships (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, pp. 131, 169 and 170).

Varadkar is a late convert to social liberalism, but he remains a fiscal conservative. In power he has evinced little enthusiasm for government investment, including describing rail travel as being for romantics. Thus far Leo-Liberalism has entailed doing very little to alter Irish society. Inactivity in office might be considered an attribute, but this predisposition suggests little will be done to tackle the current housing crisis, or address Ireland’s runaway Greenhouse Gas Emissions.

II – Double-Jobbing?

Leo Varadkar is a preternatural politician, an exotic insider who has, with great alacrity, climbed the greasy pole to become the youngest Taoiseach in the history of the state, while others around him floundered. In achieving this impressive feat he has displayed unmatched understanding of the dark political arts, which Niccolò Machiavelli believed necessary to advance a politician’s ends. But the Renaissance Italian warns his Prince to shun flatterers.

A recent biography Leo: Leo Varadkar – A Very Modern Taoiseach casts Varadkar as ‘the tall, dark and handsome’ icon of the new Ireland, whose ‘photographic memory’ (a facility also once attributed to Garret FitzGerald) allowed him to waltz through a medical degree on this way to high political office (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, pp. 15 and 39). This ‘young foggy’ honed his abilities in the trenches of student politics alongside comrades, many of whom have now fallen by the wayside – a recurring theme throughout his career – such as Lucinda Creighton.

The two young authors appear close to the subject, to the point where dispassionate assessment is not apparent: one, Niall O’Connor, was recently appointed a special adviser to the Ministry of Defence; the other Phillip Ryan is deputy political editor across the titles of the generally pro-government Independent Newspaper group, owned by Denis O’Brien.

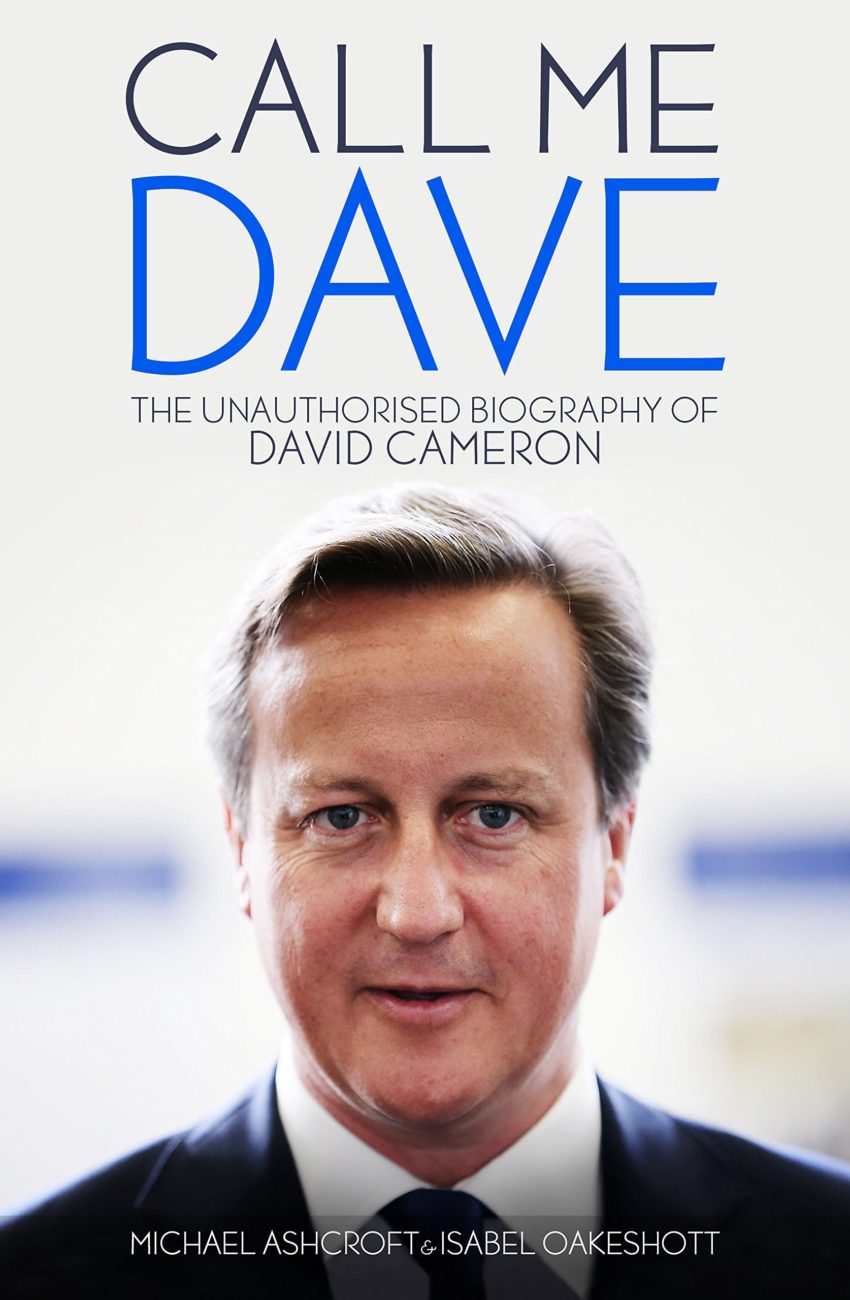

Call me Dave.

The book was published by Biteback Publishing, partly owned by Tory grandee and billionaire Lord Ashcroft, which also released a biography of David Cameron Call Me Dave: The Unauthorised Biography of David Cameron (Bitback, London, 2015), co-written by Ashcroft himself, alongside works attacking the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn.

But as any historian is aware, an apparently tainted source may nonetheless yield valuable evidence. Time will tell whether our Prince has erred in allowing damaging material to enter the public domain.

In his review of the book Diarmuid Ferriter drew attention to a passage explaining how Varadkar: ‘floated the idea to one TD of creating anonymous accounts to make positive comments under online stories on popular news websites.’ But it seems likely that this going on in political parties across the board.

Far worse was Varadkar’s conduct while Minister for Social Protection (2016-17), where he launched an advertising campaign against welfare ‘cheats’. In the meantime he used the Department as a launchpad for his leadership bid, after first hatching an escape from the ‘Angola’ of Health.

An unnamed adviser relates how visits to Intreos, Department offices located in every county, were used to further his ambition to lead Fine Gael: ‘Social protection was great for us … We travelled everywhere. We went to every parish hall. Every councillor we got to meet. The campaign indirectly started when we were meeting councillors’ (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.254)

Masquerading as Department business, these were tours on what former Fianna Fáil leader Charlie Haughey called the ‘rubber chicken and chips circuit’ of constituency branches, all at the expense of the Irish taxpayer. Considering Varadkar’s attacks on ‘welfare cheats’, this double-jobbing is the height of hypocrisy. Such conduct may be normal in Irish politics, but that does not make it right.

Unfortunately, doing little, while generating a lot of noise, marked Varadkar’s stint in the Department of Social Protection, as has been the case in his other roles.

What also emerges is just how embedded many of the most influential journalists in the country appear to be. The authors unashamedly reveal how the ‘Taoiseach has made a virtue out of wining and dining journalists who accompany him on international trade missions’, believing, ‘it is important to spend time with them socially’.

During one recent jolly in New York, ‘More than twenty guests, who included journalists from print and broadcast media, joined the Taoiseach and foreign affairs officials for a five-course, three-hour-long meal’. The authors, who may have been present, gleefully recall the guests devouring ‘French onion soup, foie gras, filet mignon and mushroom ravioli dusted with black truffles’, followed by further drinks in Fitzpatrick’s Manhattan Hotel in Midtown; all, we may assume, at the expense of the Irish taxpayer (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, pp. 321-322).

Few journalists could resist the prospect of such intimacy with a sitting Taoiseach, fewer still could emerge from such lavish entertainments with objectivity intact.

The attitude of one of his predecessors John A. Costello, who inveighed against ‘the era of the expense account … the era of the expensive restaurant (McCullagh, 2010, p.390)’, has long since fallen into abeyance.

It should also raise an eyebrow that Ryan Tubridy, Miriam Callaghan (both of RTE) and Ursula Halligan (of TV3) endorse the book on the back cover.

III – ‘Dr’ Varadkar

In Irish society, as with many others, the position of doctor carries an unmatched aura of respectability. As the son of a respected G.P. Leo had an immediate advantage of name recognition, and respect, in his constituency when he began his political career.

In the meantime he was studying for a medical degree himself, though he admits he was a dilettante student, and perhaps ought to have studied law, that other passport to bourgeois respectability. Nonetheless, training to be a doctor has given this career politician an enduring credibility, and mystique, which still impresses commentators.

As a young councillor, we are told he would travel ‘straight from hospital to the chamber dressed in his medical attire, with a stethoscope around his neck’. He now denies the full extent of this, but the nickname of ‘Scrubs’ that emerged in the local media, was hardly damaging (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.52).

His biographers claim that medicine is among the interests that Leo shares with his partner, Matthew Barrett, who is a practising cardiologist, but as Minister for Health Varadkar showed a discernible lack of interest in staying in the job. An anonymous cabinet colleague remains critical:

The fact he walked away from it after such a short time, I think if you ask most of the parliamentary party, even some of his biggest supporters, they were disappointed with that. It was obviously done with a view to the leadership election. There was obviously a calculation made that you cannot go from health to the Taoiseach’s office. Certainly not in a contested election when you have to go around canvassing (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.235)

One might have expected a young doctor to be brimming with ideas on how to address the major public health questions of our time – just as Dr Noel Browne spearheaded efforts to eradicate T.B. when he was Minister in the late 1940s – or even dismantle the expensive bureaucracy in the health service.

Varadkar’s first decisive move, just two weeks into office, was to abandon the Coalition government’s promise, and long-term Fine Gael commitment, to universal health insurance (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.154). He went on to boast publicly that he had taken out his own private insurance, and urged other young people to follow suit.

The two-tier system would remain, and nor was Varadkar prepared to reform what remained of public provision, and dispense with the Health Service Executive: that layer of bureaucracy insulating a Minister from direct criticism, bequeathed by one of his confidantes, former Minister for Health (2004-11) Mary Harney.

After Kenny’s calamitous election campaign in 2015, when the party lost twenty seats, Varadkar knew his time was nigh. He forced his way out of Health by demanding ‘a large bag of cash and a mandate for sweeping change’, whereby he could bypass the rules surrounding recruitment (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.232). These were demands he knew Kenny would not be accede to. The doctor had more than Health on his mind.

The Reluctant Taoiseach: John A. Costello.

IV – ‘Murph’ and the Whistleblower

It seems the Housing ministry has become the new ‘Angola’ among government Departments, with any Minister operating with fiscal and monetary constraints over which he has no control. The incumbent, whether Simon Coveney or Eoghan Murphy, appears like a hapless pilot frantically playing with the instruments on an already doomed vessel as it descends through the sky.

To make real progress, the Ministry of Housing would have to be develop a construction agency headed by the minister, integrate with the Transport Department, and be given a direct line to Finance. Instead the Housing Building Finance Bill 2018 ‘will provide financing to developers seeking to build viable residential development projects in Ireland on commercial, market equivalent terms and conditions.’

Varadkar’s long-standing resistance to asking those who “pay for everything” to provide any more, does not appear to preclude a revival of the public-private partnerships which were a hallmark of Bertie Aherne’s tenure as Taoiseach.

Yet the account of Eoghan Murphy that emerges in this biography does not align with the bumbling, statistic-addled media performer, labelled the ‘Craig Doyle of Irish politics’. He was Leo’s loyal fixer, largely responsible for Varadkar capturing an overwhelming share of the parliamentary party’s vote.

Varadkar’s Fixer: Eoghan Murphy.

According to one of his colleagues: ‘You had to have a multiple ways into people and no one moved into a “solid yes” unless Murphy was 100 per cent satisfied (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.277)’.

Murphy was the founder of the so-called Five-A-Side Club of young Fine Gael TDs and at one point the sole member in Varadkar’s corner. As such, he was crucial to the latter’s rise (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.125).

Murphy’s gregariousness compensated for Varadkar’s frank admission that he ‘probably should not be in politics at all; I am not really a people person (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.112)’. Unlike Varadkar however, and perhaps to his cost, Murphy appears quite serious in his attempts to govern. He will remain a lightning rod for dislike of the government, however, as long as the state continues to shirk a constitutional responsibility to provide affordable accommodation for citizens.

When Enda Kenny finally resigned from office last year, apparently after egotistically ensuring he had surpassed John A. Costello as the longest-serving Fine Gael Taoiseach, Varadkar’s main rival Simon Coveney was hit with a political blitzkrieg, foreclosing any leadership race before a shot had been fired in anger.

From his free-roaming position in Social Protection Varadkar had captured the vast majority of the parliamentary party, making the 65% of the vote Coveney received from the wider political party an irrelevance.

What had brought Kenny down, along with two Ministers for Justice and two Garda Commissioners, is perhaps the greatest scandal in Irish public life since the turn of the century: the alleged framing on charges of child sex abuse of the Garda whistleblower Maurice McCabe after he had revealed industrial scale non-prosecution of drink-driving charges. This has led to the appointment of the first Garda Commissioner from outside the state.

In this regard at least, Varadkar has been on the right side of history, famously referring in the Dáil in 2015 to McCabe (who he had previously met and appraised) as an ‘honourable man’, after his conduct had been described as ‘disgusting’ by then Garda Commissioner Callinan.

The one part of this narrative that rankles, however, flows from the toxic relationship that existed between Varadkar and Alan Shatter, who as Minister for Justice appears to have been mislead by senior Gardaí. Did Varadkar’s own ambitions inhibit him from reaching out to a cabinet colleague? The political cadavers the affair made of so many of the Fine Gael old guard certainly cleared the way for Varadkar.

Nonetheless, Varadkar must be given credit where it is due, and many of his ideological opponents were impressed by his respect for Justice and the Rule of Law. This impression is bolstered by his rejection of an idea floated by the current Minister for Justice Charlie Flanagan for a ban on Gardaí being photographed in the course of their duties.

V – A Land of Opportunity?

It seems de rigeur for any fiscally conservative politician to display a commitment to ‘opportunity-for-all’ when he ascends to high office. Thus, in his acceptance speech Varadkar urged ‘every proud parent in Ireland today’, to dream ‘big dreams for their children’.

He said:

Let that be our mission in Fine Gael, to build in Ireland a republic of opportunity, one in which every individual has the opportunity to realise their potential and every part of the country is given its opportunity to share in our prosperity (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.xi).

Opportunity for Varadkar is distinctly upwardly mobile, along the lines of the American Dream, which has been fools’ gold for many. Nothing is said of those who inevitably fail to live up to their own, or parent’s, aspirations, and depend on the state for help. His approach seems at odds with John A. Costello’s Fine Gael being, ‘for all sections of the Irish people, but particularly for the poor and the weak and the distressed (McCullagh, 2010, p.398)’.

Perhaps the one measure that would achieve the parity of opportunity which Varadkar claims a devotion to, would be to develop a truly equal educational system. But the best model for primary and secondary education seems to be found in Finland, where private schooling is effectively prohibited, and educational attainment among the highest in Europe. Instructively, this socialist society maintains an income tax rate in excess of fifty per cent.

Varadkar has in the past opposed reforming the Irish education system, where the state pays the salaries of teachers in the private institutions, which achieve the highest grades in state examinations. In 2003, he said dividing Ireland ‘into a country of those who pay for everything and receive nothing and those who pay for nothing and receive everything, with only a small minority in between, would deal a fatal blow to what is left of Ireland’s social contract (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.52)’.

There is perhaps no clearer statement by Varadkar of whose interests he would serve in fulfilling his “contractual” role: those who “pay for everything”, the wealthiest strata of society who have throughout the history of the state used educational attainment, including access to careers in medicine and the law, as a barrier to wealth and influence.

That affiliation has been apparent from the beginning of his political career: with his excoriation of the social democratic tradition in his party; it proceeded through an inclination to work with the Republican Party, and sympathy for the Progressive Democrats; it showed in a willingness to dispense with a promise of universal healthcare and accept a two-tier system, and with the shaming of welfare ‘cheats’. It was also apparent in his entreaties on behalf of Donal Trump’s Doonbeg golf course, and open invitation to visit the country.

Leo’s liberalism is uniquely adapted to further his ambitions, and take care of his supporters. The Prince appears to have no plan beyond the end of achieving power, and it trappings.

In a revealing aside in this most beige of biographies we discover him telling colleagues ‘he feels at his most comfortable when holding meetings with other world leaders, some of whom he regularly texts’. Most worryingly perhaps, he has also ‘struck up warm relationships with’ among others the Far Right Hungarian President Viktor Orban (Ryan and O’Connor, 2018, p.319).

*******

Times have changed in Irish politics, where once John A. Costello had to be persuaded to serve as Taoiseach, today a career politician unashamedly plots a course to power. Who would wish to enter this tawdry scene? Micheal O’Siadhail’s insight appears apt that ‘the thieves of power / Come noiselessly in nights of apathy (O’Siadhail, 2018, p.149)’.

Raising political standards in Ireland goes far beyond removing Varadkar, who is a product of a political system informed by clientalism. It requires an evolution in our understanding of the role of government, and a shared acceptance of the need for genuine equality of opportunity, beginning with educational reform.

Varadkar’s own party is now what he and others aspired for it to become: a conservative party, untainted by social democratism, which wields power on behalf of the property-holding, private-school-attending, privately-medically-insured cohort of the population. As long as he remains in power those who “pay for everything” will remain ascendant.

References

David McCullagh, The Reluctant Taoiseach: A Biography of John A. Costello, Gill and MacMillan, Dublin, 2010.

Philip Ryan and Niall O’Connor, Leo: Leo Varadkar – A Very Modern Taoiseach, Biteback Publishing, London, 2018.

Micheal O’Siadhail, The Five Quintets, Baylor, Waco, 2018.