I am sticking my neck out to declare: Micheal O’Siadhail’s book-length poem, The Five Quintets, is the most important work of English-language literature that has been published so far this century. O’Siadhail’s towering achievement melds reflections on the arts, economics, politics, philosophy and, fascinatingly, science into lyrical verse that transfixes the reader. He urges we enter a paradise of compromise, love and engagement, whilst crisscrossing the disabling specialisms that bedevil our time.

Inspired in particular by Dante Alighieri’s thirteenth century journey through heaven, hell and purgatory in The Divine Comedy, O’Siadhail introduces us to men especially, and women, who have shaped, and distorted, our modernity. The Italian poet himself is channelled, offering to guide O’Siadhail’s journey through hell to ‘heaven’s vertigo’, ‘And summing up an era work the seam / Between the modern world and its aftermath’.

T.S Eliot’s influence also lurks in the poem’s title – an allusion to his The Four Quartets – which, O’Siadhail writes in the introduction, ‘feels it needed a fifth part’, as it ‘never really gets to the joy and let-go of an imagined heaven’. The influence of that American poet is held in check, as this literary shark, ‘demands an absolute / To order seas of doubt which rage inside’.

Moral absolutists are, without fail, scorned in O’Siadhail’s schema. The heaven which he glimpses is never fixed, but in play, and informed by the principle of uncertainty. Similarly, utopia, ‘no place’, is a term frequently used to denigrate those theorists whose intellectual pride obscures a vision of an elusive paradise.

O’Siadhail’s muses are numerous, but ‘Madame Jazz’, an earlier incarnation, acts as a Virgil-like sidekick throughout.

Although each sacred book’s a lip-read score,

Improvising there is always more;

You jazz on what’s our own and our rapport.

Each solo and ensemble of a piece,

Grooves and tempos shifting without cease,

We flourish in a syncopated peace.

In all our imperfections we advance,

Trusting in creation’s free-willed chance;

Sweet Madam Jazz, in you we are the dance.

Her gyrations allow O’Siadhail to fix on a horizon in constant, though not immediately apparent, motion.

In the final section, we also encounter Dante’s Beatrice, who perhaps best captures the rupture which O’Siadhail’s work seeks to heal:

You mortals down below can fail to see

how marvels coded in the universe

reflect the face of God’s infinity.

Too graceless, too constrained, you still immerse

yourselves in steps and miss out on the dance –

the scientists and poets don’t converse

or celebrate each quantum of advance,

discovering a heaven’s cameo

in God, the gambler’s mix of love and chance.

Laurens van der Post wrote: ‘For me the passion of spirit we call “religion”, and the love of truth that impels the scientist, come from one indivisible source, and their separation in the time of my life was a singularly artificial and catastrophic amputation.’ O’Siadhail’s work may help restore a moral compass to the great scientific adventures, which have brought mastery over planet Earth, but often with unintended, or unacknowledged, costs. Religious, including many poets, in turn, might no longer see themselves as being in opposition to science, but in fruitful communication with its inherent mysteries.

II – The badger and the fox.

In the first quintet, Making, we meet a host of writers, musicians and artists, who are assigned in haikus (or ‘saikus’ – a neologism) an animal or plant spirit. These are followed by carefully crafted sonnets, combining narrative accounts and artists’ voices, channelled through O’Siadhail. He rhapsodises on the achievements of many, but there are stinging observations on the artistic limitations, or myopia, of others.

Thus, William Wordsworth’s legacy is tainted by a failure to generate the epics he had dreamed of, his Prelude represents: ‘All Foothills to the peaks you never reached’; while Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s ‘Youth’s promise’ was diminished ’in opium’s malaise’.

That arch-worrier Franz Kafka is consigned to a ‘sleepless hell’, as O’Siadhail condemns him for feeding ‘… the wizened dreams of minds withdrawn / Your nightmare’s broken trust denying dawn.’ While Pablo Picasso has become, ‘A famous for being famous millionaire’, unhinged by fortune and acclaim.

For others there is reverence, including Fyodor Dostoyevsky, for never deviating from a desire ‘to stanch life’s sufferings’, and having, ‘No truck with any cause but moral truth’. In his compassion we find a ‘glimpse of paradise’.

Classical composers including Ludwig van Beethoven, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Gustav Mahler and J. S. Bach are also celebrated, but Richard Wagner, ‘a lone wolf’, is condemned for mustering dark nationalistic forces. Elsewhere, O’Siadhail’s George Frederic Handel conveys the sublime balance of his oeuvre.

I only want to hold the music’s line

A flighty psyche focused on its goal

So every voice can shine but not outshine,

From all the woven parts create the whole.

Painters are less evident among these shades, but his description of Francisco Goya’s ‘Third of May’ ’merits retelling:

Where fusiliers have turned their nameless back

And bend to execute their point blank prey;

My lamp of pity lights the victim’s face.

The ‘Third of May’, by Francisco Goya.

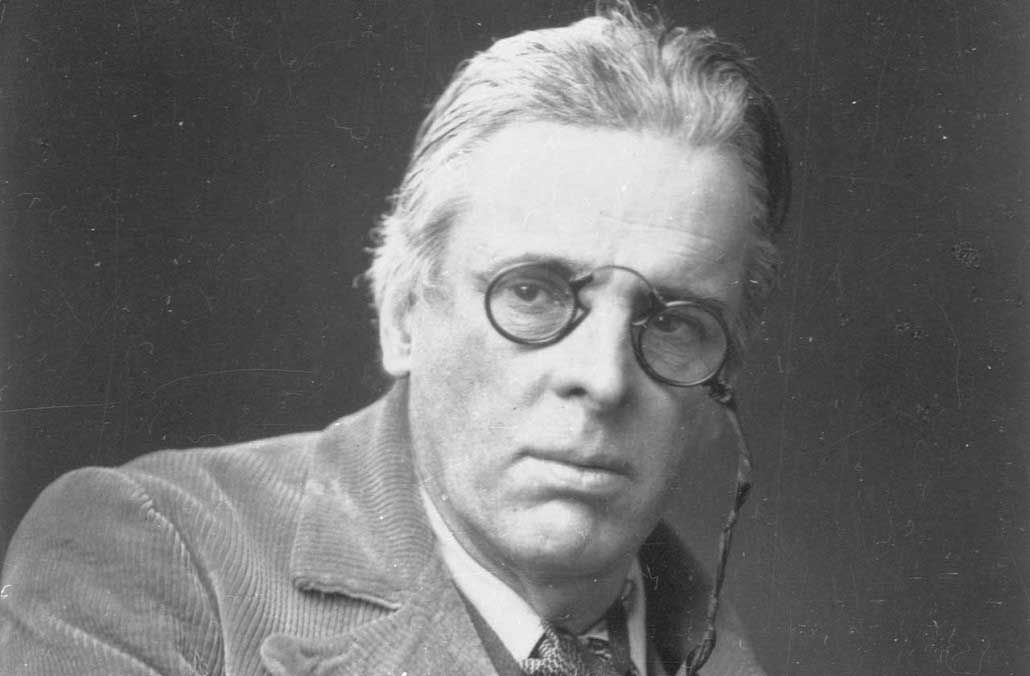

Irish readers will be intrigued by his encounters in our literary pantheon. Suitably, W.B. Yeats is depicted as a badger, ‘the churning digger / With its nose close to the ground’. O’Siadhail hails him as ‘the archpriest of sound’, and, unusually, integrates and adapts many of his lines, such as ‘Old lecher with a love on every wing’, from the still smouldering Tower.

But there is a stern rebuke for his promotion of eugenics: ‘scorning base-born products of base beds’, and unwillingness to look beyond a fantastical world that is, ‘dead and gone … That perfect past your mind’s own cul de sac’. Instead O’Siadhail urges: ‘Retrieve best thoughts once shed and then move on’.

Characterised as a badger, W.B. Yeats.

O’Siadhail is similarly conflicted over James Joyce’s legacy, admitting to loving a language ‘burbling up in play’. From one great linguists to another, O’Siadhail tells him he is as good a reader as, ‘you’ll get to understand your punning riverrun’, but counters, ‘I know the charge of words, and yet and yet’.

He wonders if his fellow Jesuit-educated writer’s works hold, ‘a microscope that is too small in scale’, and whether, ‘in the end does anything take flight’. This might come as a relief to those who have baulked at Finnegans Wake’s circumlocutions.

O’Siadhail is suspicious of a character ‘so proud and so obsessed’, for whom others are ‘walk on parts in your world’s play’. He scorns the, ‘dreamlike doodling of an introvert’. But there is high praise indeed for Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in Ulysses, including a playful pun of his own:

Still once at least, though in a woman’s voice,

I didn’t pun or try to be opaque

But spoke my shortest playful work of praise

And yes, in Molly’s yes I did reJoyce.

The other two Irish writers we meet are Patrick Kavanagh, ‘A kamikaze trusting in God’s wind’, who, ‘In hungry times’, paid the price’, for being a ‘peeping Tom who lusts for paradise’; along with praise for Brian Friel’s ‘impish wit’.

Notably absent are Seamus Heaney (who has perhaps been canonized prematurely?), and Samuel Beckett. Elsewhere O’Siadhail has criticised the interiority of Modernists, who refused to take responsibility ‘for shaping a wider meaning’. He continues:

Apart from the risk of solipsism and plain self-indulgence, there is the risk of turning poetry into a kind of private piety, which ends up marginalising poetry or branding it as some kind of academic pursuit not appropriate to the ordinary reader of books.

Refreshingly, however all-encompassing his themes, O’Siadhail’s language is never self-indulgent, and always endeavours to inform.

III – ‘The Dismal Science’

O’Siadhail tells the story of the making and undoing of our modernity by theorists and movers and shakers, as he seeks to reshape our current approaches. The self-imposed constraints of metre, and often rhyme, bring a pleasant economy of expression.

O’Siadhail’s ambition to tell the story of our time in The Five Quintet recalls the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphosis, which draws together the mythologies that informed an understanding of the ancient world in order to forge a new consciousness. Here the Classical titans give way to seminal figures such as Adam Smith, Karl Marx, Thomas Malthus, Karl Marx, J. M. Keynes, Milton Friedman and Amartya Sen, along with men of commerce, who are today often vemerated as heroes.

The bargain struck, the business done,

The dealer’s will and drive for wealth,

Our new concern with number one.

One self-interested specimen on display is Ireland’s own Michael Fingleton:

Still bent on short-term deals to boost

A bottom line. A bonus-gained,

Already on your way to ruin

All caution to the winds – who cares?

Ambitious tiger burning bright

And brazen in your riot-run

You do not know the dust you’ll bite.

It seems unlikely O’Siadhail sought legal advice on the potential for defamation in this section. It would certainly make for quite a trial to find the poet in the dock against the disgraced banker. A defence of justification should be available for the following lines:

Small loaners find you’ll go to law

To take your pound of flesh to pay

What’s owed; for bigger borrowers

You bend or buck to make the rules,

Indulge whatever debts occur.

There is a nuanced treatment of Adam Smith’s contribution to economic theory. Laissez faire, permits ‘the hidden hand’ to operate, leading to competition which generates efficiencies, but which at all times requires vigilance against ‘crafty dealers’ in league, ‘to fix a price and profit by intrigue’.

O’Siadhail’s ‘modern mind’ cannot understand, however, Smith’s failure to rail against children being harnessed in black holes ‘Deep down in Durham’s shafts and pits’. He also points to the irony of merchants, ‘Whose mean rapacity you taunt’, adopting Smith as their first forebear.

O’Siadhail has interesting reflections on Robert Malthus, who may yet be vindicated in his prediction that food production capacity will not keep pace with the demand of a growing population:

Your thesis bites so near the bone.

Malthusian views now haunt our thoughts;

These times will know a darker tone.

Is this the onset of a devastating Climate Change he is referring to?

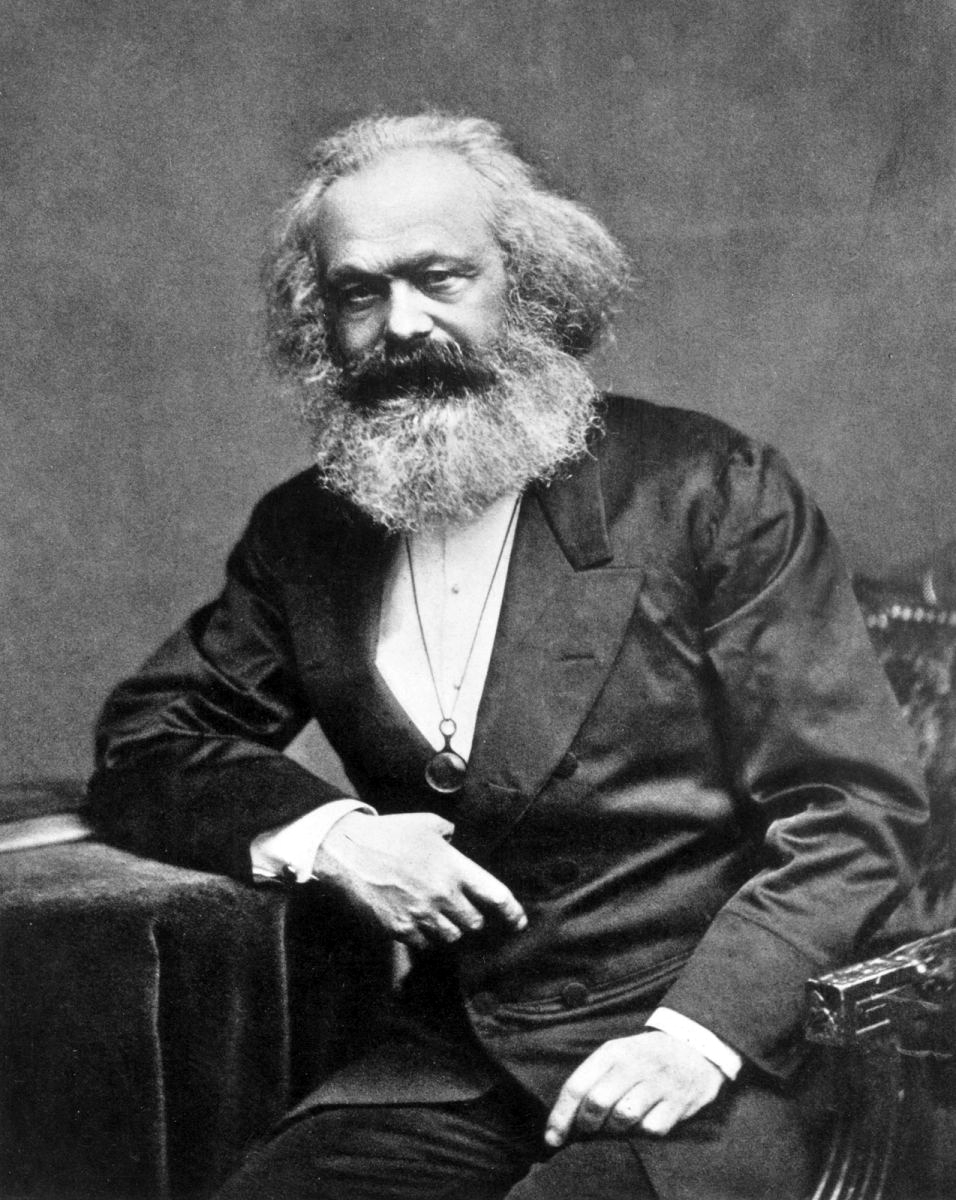

O’Siadhail is conflicted in his appreciation of Karl Marx, hailing him as a visionary who foresees ‘as no one else had seen’, that four hundred billionaires would hold just half our wealth, alongside the ‘constant gyres of boom and bust’, apparent in late capitalism.

Karl Marx, ‘a know-all coldness’.

But according to O’Siadhail, the Communism that Marx imagines contains a core failing evident in its designer, ‘a know-all coldness at your core’. Indeed, being a ‘know-all’ is an oft-repeated barb, leading to the delusion of utopia. This point is central to O’Siadhail’s diagnosis of what has brewed many of our present troubles. Thus Marx is condemned for failing to conceive of compromise, ‘Where conflicts would be reconciled’.

We also meet J.M. Keynes who learns by listening to his peers, and is thus lionised as a ‘Soft changer, saint of step by step’, who recognises how, often, only government stimuli will lift an economy out of the doldrums:

The system does not cure itself;

So maybe it needs money lent

To make it flow and multiply

Far less favourable is O’Siadhail’s assessment of Milton Friedman, another ‘know-all’, whose rigour ‘will room no doubt / Your mind demands all black and white’. While acknowledging he served up some neglected thoughts, O’Siadhail chides him for using Keynes’s ‘one defect’ – of failing to appreciate the significance of monetary supply – to justify opposition to all state interference with the ‘hidden hand’.

Instead we find: ‘Free flow finance gives quick-fix gains / But blows up bubbles that must burst’, where, ‘The wily then are winners all’. O’Siadhail plumbs for the Scandinavian laws: ‘Where weak need not go to the wall’.

One Scandinavian theorist we meet is Thorstein Veblen, who reveals an acute understanding of why workers are not always sympathetic to Marxist ideas.

Society does not cohere in hate–

All workers really want to emulate

Their boss – the weak are would-be rich at heart;

If Marx had not been wrong and me not right

The poor would tear society apart.

O’Siadhail sees a need for more than Marxist materialism to meet the challenge of inequality. The height of wisdom arrives from a woman, and ‘cub economist’, Kathryn Tanner, who finds in the ‘love-dream born of Bethlehem’ the possibility of mending the distortions of the market place.

Tanner, through O’Siadhail, says:

Is this utopian, I hear you ask,

A heaven here on earth, a hopeless task,

Another revolution run roughshod?

O no! It’s here and now we must uphold

The common right of all to gifts of God.

This is perhaps Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s ‘Christianity of this world’, grounded in earthly challenges, rather than lofty metaphysics. One might also discern the influence of his intellectual brother-in-arms the theologian David Ford.

IV – The Art of the Possible

The next section, entitled Steering, meditates on good governance. O’Siadhail decries the fantasists of left and right, while bemoaning ‘tweedle dee’ and ‘tweedle dum’ politics, such as we find in Ireland. He warns: ‘the thieves of power / Come noiselessly in nights of apathy.’

O’Siadhail’s continues to inveigh against ‘know-all’ attitudes, warning the reader to guard against the real sympathies of utopians.

Fear ideas that outreach the heart,

Chilled compassion of the ideologue.

What purports to pity broken lives

Often hides a know-all arrogance

That wants to own the future and the past,

So refuses, starting from the now.

Greedy for the perfect all create

Hells of blood and soil and golden age.

Readers might be intrigued by his descriptions of Margaret Thatcher, ‘Forthright Grantham grocer’s girl’, as an autocrat. Her parvenus attitude reflects Thorstein Veblen’s earlier insights into the aspirational, “would be rich”, working class:

Some who shin the tall and greasy pole

Carry in their bones a sympathy,

Want to spare all comers such a climb;

Others vaunt their courage and condemn

Weakness they had fought to overcome,

See all frailness as a threat to power.

Margaret Thatcher: tearing apart society’s ‘love-ravelled fabric’.

In O’Siadhail’s account Thatcher is prompted by Keith Joseph, ‘To rethink all in Milton Friedman’s words’. This leads to the tearing of society’s ‘love-ravelled fabric’.

There is also an intriguing description of the arch-networker, Jean Monnet, one of the original architects of the European Community. O’Siadhail traces the current fraying of the Union right back to the failure of Monnet and others to conjure, beyond simply commerce and trade, a European identity, based on ‘deeper bonds and ties’.

Perhaps writing in the wake of the Greek and Irish bailouts, O’Siadhail seems wary of ‘Brussels’ one-fits-all’ approach:

Starred blue flag so dutifully raised,

Still not fluttering in our chambered hearts

Heaven is no timeless superstate.

In Canto 5 of this section, ‘A Beckoned Dream’, O’Siadhail reveals a political paradise comprising of William Ewart Gladstone, who accepted Irish Home Rule, Mahatma Gandhi, Dag Hammarskjold, the ‘United Nations’ guiding star of peace’, Nelson Mandela and, less convincingly, former Irish President Mary McAleese, who is commended for building sectarian bridges among ‘Ghosts of Europe’s once religious wars.’

I found this choice puzzling as McAleese was more of a figurehead as Irish President, and did less to interrogate the rising tide of inequality in Ireland than her successor Michael D. Higgins. Moreover, McAleese was an electoral candidate (in the 1987 General Election) for Fianna Fail under the corrupt leadership of Charles Haughey, who also tactically rejected the reconciliatory Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, and her Presidential candidature came during the tenure of another tainted figure in Bertie Ahern.

I would prefer to have seen greater emphasis on environmental responsibility in this cockpit, as humanity stares down the barrel of self-inflicted ecological collapse. Perhaps some will be frustrated by the idea that political change cannot arrive more quickly than in ‘Fractions less imperfect than before’, considering the challenges that now press against us, but his emphasis on the value of dialogue is surely correct: ‘Gaze-to-gaze in our humanity / Enmity we can thaw … ’

V – God and Science

The two final cantos Finding and Meaning, covering Science and Philosophy, might stretch most readers more than the first three; although O’Siadhail never succumbs to drawing too liberally from his rich pallet of languages and knowledge. It will be intriguing to encounter scientific responses to his account of the great leaps forward in our understanding of the universe.

Following his rejection of the fixity of political utopias, O’Siadhail sees a cosmos born of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, as opposed to a ‘knotty crossword yielded clue by clue’ that is capable of completion. Here we encounter a God that plays dice.

In Meaning, O’Siadhail continues to riff (in Dante’s own terza rima) on the unknowableness of the divine:

Allow our God a purpose not our own

and here outside a timeless roundelay

we dance within our fragile ecozone

Here we meet the shades of Martin Luther, John Calvin, Rene Descartes, John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and a sneering Friedrich Nietzsche, who is condemned for a lack of compassion, and an unwillingness to compromise, yet:

Despite his detached mind’s strange solitaire,

for all mad Nietzche’s overreaching claims,

his genius shows how humans overbear;

Next come Sigmund Freud, Bertrand Russell, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre – dismissed as a ‘a braggadocio of angst that sinks / to vanish in the nothingness of hell’ – Søren Kierkegaard, Emmanuel Levinas, Paul Ricouer, Said Nursi, and Jean Vanier, who wonders ‘What if the weak become our first concern / what if such love decides our balance sheet’.

Vanier also offers encouragement to the poet:

this poem may be a slow fuse to guide

the moments in our psyches which allow

an amplitude, a deeper second sight.

Then Hannah Arendt again condemns:

Utopians who weave their gossamer

ideal never see the here and now;

for such far sight the present blur,

We also meet O’Siadhail’s first wife, who died some years ago after a long illness:

In your compassion, Bríd, I think I grow

and understand how only love can heal;

I learn to feel what others undergo.

Finally, there is a dreamy vision of Paradise in which O’Siadhail travels along a path between two parallel rows of trees each ‘interwoven with its counterpart’, ‘in curves of paradox which shape the light’.

VI – Poetic Futures

O’Siadhail’s The Five Quintets synthesises many of the great intellectual questions of our time. In so doing O’Siadhail fits Robert Graves’s description of a poet as, ‘the unsatisfied child who dares to ask the difficult question which arises from the schoolmaster’s answer to his simple question, and then the still more difficult question which arises from that.’ O’Siadhail keeps asking the big questions, having refused the easy chair of academia, where poetry often becomes an obscure word game, and a private members’s club. Authentic poetry may still be difficult, but this arises from considering profound questions.

The length of The Five Quintets also poses the question as to whether long form, epic, poetry may come back into vogue.

Previously, the Canadian literary critic Northrope Frye argued that Edgar Allan Poe’s essay ‘The Poetic Principle’, published posthumously in 1850, had a ‘tremendous influence on future poetry’. Poe proposed that a long poem was a contradiction in terms, and that all existing long poems of genuine quality consisted of moments of intense poetic experience, ‘stuck together with a connective tissue of narrative or argument which was really versified prose.’

Frye regarded this as preposterous, but a preference for brevity, which may mask a lack of ambition or vision, is still apparent.

May we revisit a Romantic Age to recover long form poetry, when poets, such as Coleridge and Shelley, were participants in scientific debates? Indeed the word science was only coined in the 1830s. Since then it has become the preserve of specialists.

The master poet. Image (c) Julia Hembree Smith.

I was a little disappointed not to meet the shade of Shelley, who had less than thirty years to impart his genius. Perhaps O’Siadhail shrank from the apparent violence of his near namesake’s earlier pronouncements on the ‘necessity’ of atheism and the revolutionary sentiments of much of his early verse, but over the course of his short life his outlook mellowed.

Just as Shelley’s challenged vested interests, similarly I suspect The Five Quintets will make some readers distinctly uncomfortable: first, it exposes gaping holes in most of our appreciation of the wonders of human thought and creation; secondly, it challenges the social and economic structures we live under; thirdly, it dismisses the delusional quick-fixes of utopians; finally, he challenges a prevalent view that religion and science are irreconcilable.

I also anticipate that the poem will only be given the credit it deserves in Ireland once it has received the imprimatur of international critics.