The cruellest aspect of protracted displacement is a descent into the realms of collective forgetfulness, in places where social injustice and political abandonment are normalised. Fresh from her fourth visit to Lebanon, author and activist Bruna Kadletz sees the Palestinian cause being relegated more and more to the margins of global concern.

In the autumn of 2017 I met three Palestinian elders at the Shatila Refugee Camp, in Beirut, Lebanon. All are survivors of Al-Nakba, meaning ‘disaster’ or ‘catastrophe’. The expression refers to the period during the violent birth pangs of the Israeli state in 1948, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were expelled from their villages and forced into exile. Many of the survivors and their offspring still live as refugees in Lebanon without a right of return to their homeland in sight.

To the elders, memory, oral history and tradition are essential pillars which sustain Palestinian identity. Otherwise, given the hardships of exile in refugee camps, the generations born expatriated are at risk of forgetting not only who they are, but also about the land of their ancestors.

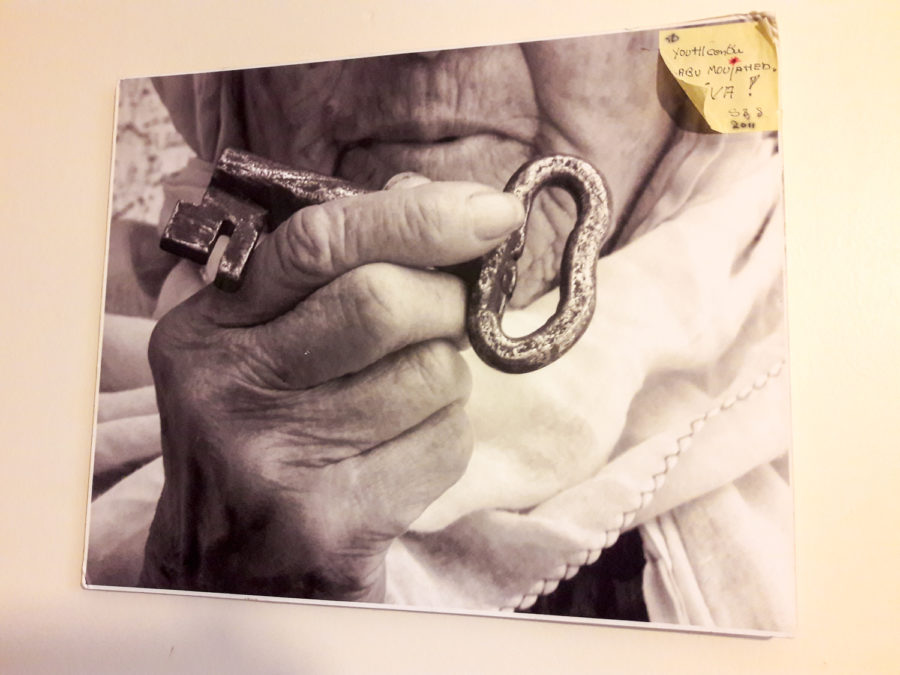

For millions of refugees around the world, home is an untouchable beloved, imagined in the sweetness and pain of memories, and only visited in the imageries of storytelling. Many Palestinians still carry the keys to their former homes in Palestine, symbolizing an unwavering desire to return. This dream of home is their life breath.

Holding a misbaha in one of his hands, while moving prayer beads through his fingers, Abu Mahmoud and other elders talk about the Occupation’s deep wounds and transgenerational trauma, as well as community and ties to the land. In the old Palestinian villages, sharing and a sense of community were central values integrated into personal relationships and the economic system.

To the villagers, the land held a deep meaning – involving devotion to the soil out of which figs, olives, wheat, among other crops, grew – and was not seen as a commodity, with a purely financial price. Before selling their produce, tradition demanded a share be reserved for the wider village community. This practice ensured all residents generally had access to sufficient nutritious food.

This camp where the elders now reside lies far from those childhood memories. Shatila, along with another dozen camps in Lebanese territory, was set-up in 1949 in response to the Palestinian exodus. Today, there are approximately four hundred and fifty thousand Palestinians registered in refugee camps in that country.[i] Since the beginning of the Syrian War in 2011 the camps have been swollen further by the arrival of Syrian refugees.

Being Brazilian, when I first entered an urban refugee camp in Lebanon, I was reminded of our favelas. The structure and living conditions of favelas and urban refugee camps are very similar: overpopulation, cramped buildings, a lack of sanitation and extreme poverty are among the resemblances. Favelas and urban refugee camps are pockets of social and political abandonment, zones of exclusion and punishment, where fundamental human rights and dignified living conditions are, all too often, unattainable.

I was accompanied by my cousin Marina on my most recent visit to Lebanon in April 2019. As it was her first visit, I advised against drinking from taps, or even touching the camp´s water. Unfortunately she forgot the warning and rinsed her mouth with tap water, which was extremely salty, leaving her feeling nauseous. Most residents use this same water to wash their faces and hands, brush their teeth and bathe. I previously found it so salty that it burned my eyes.

A local told us that most of the water distributed in refugee camps in Lebanon is contaminated. Treatment plants inject high volumes of disinfectant chemicals to mask the pollution, amidst a water crisis.

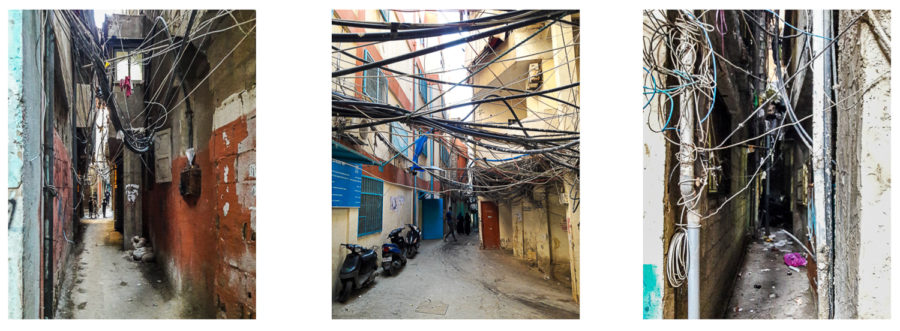

Some Palestinian camps have another singular characteristic: the water distribution system is not subterranean. Instead, water is circulated via pipes which intertwine with electric wires, forming a deadly roof, covering great swathes of the camps. Wherever a leak occurs residents are in danger of electrocution.

Because Palestinians living in Lebanon are prohibited from acquiring property in that state, and denied entry to over seventy professions, most have bleak future.

Since they cannot build beyond the camp’s walls and expand horizontally, the remaining option is to build vertically and take advantage of every square inch in the camp. As a result, there is now insufficient gaps between buildings and deficient ventilation. The sun does not shine on the narrow alleys connecting the camps.

I am reminded of a popular Brazilian saying, ‘The sun rises for all’. Underpinning this optimistic view of life, is an understanding that everyone enjoys similar opportunities in life. But having witnessed the exclusion of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, and the deprivations they endure in their daily lives, it seems to me that, for those living in alleys and ghettos, the sun does not rise at all. Alas, a growing number of displaced people around the world, like the Palestinians, inhabit this dark space of dispossession.

In August 2018, the Trump administration announced it would cease funding the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which is responsible for the protection and provision of aid to Palestinians in the Middle East.[ii] For many years, the U.S. had been contributing a quarter of UNRWA’s budget. This was part of a wider strategy of subjugating the Palestinian people by placing them in positions of greater economic vulnerability. The loss of funding is already harming projects supported by UNRWA, such as schools and medical clinics.

Yet, in spite of adversity, Palestinians remain resilient. When I think of Palestinians, I see the olive trees they love so much. Olive trees are drought-resistant and grow in poor soil. This reflects Palestinian strength, resistance and endurance. The trees and the Palestinian people can teach us how to bear fruit, even in arid conditions.

[i] United Nations relief and works agency for Palestinian refugees in the Near East, ‘Where We Work’, https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/lebanon, accessed 29/4/19.

[ii] Karen DeYoung and Ruth Eglash, ‘Trump administration to end U.S. funding to U.N. program for Palestinian refugees’, August 30th, 2018, The Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/trump-administration-to-end-us-funding-to-un-program-for-palestinian-refugees/2018/08/30/009d9bc6-ac64-11e8-b1da-ff7faa680710_story.html?utm_term=.0798b05139ba, accessed 29/4/19.