- Long Term Patterns: the U.K. Prefers Oxford University-Educated Conservative Prime Ministers.

Only Winston Churchill, and John Major among election-winning Prime Ministers since World War II did not pass through ‘the city of the dreaming spires’ during their formative educational years (neither University of Edinburgh-educated Gordon Brown nor Jim Callaghan, who could not afford a university education, won an election to become Prime Minister).

A former President of the Oxford Union, Boris Johnson (Baliol College, 1987), joins a list that includes Theresa May (St Hugh’s, 1974), David Cameron (Brasenose College, 1988) Anthony Eden (Christchurch College, 1922), Harold MacMillan (Balliol College, 1914) Edward Heath (Balliol College, 1939), and Margaret Thatcher (Somerville College, 1947), as well as Labour PMs Tony Blair (St John’s, 1974), Harold Wilson (Jesus College, 1937) and Clement Atlee (University College, 1904).

Apart from political points of difference, the well documented hostility exhibited towards Jeremy Corbyn, across the media spectrum, since he was first elected party leader[i] may be attributed to bias (unconscious or otherwise) against an individual perhaps deemed to lack the necessary polish – or debating skills – conferred by the elite institution.

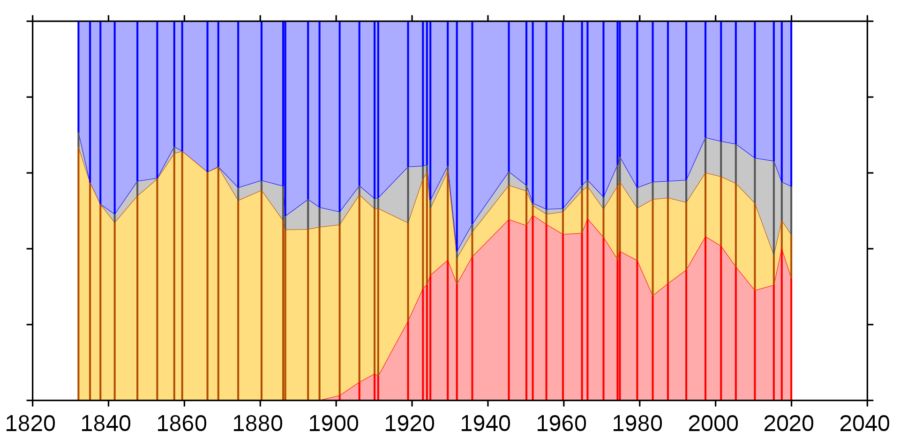

Moreover, it is clear that Conservatism, an admittedly amorphous and pragmatic body of ideas, fluctuating historically between pro- and anti-European Community positions, represents the mainstream of British politics, with the Party holding power for forty-four of the seventy-four years since the end World War II (or 60% of that time); rising to twenty-seven out of the last forty years (or 68% of the time since 1979).

Shares of the vote in general elections since 1832 received by Conservatives (blue), Liberals/Liberal Democrats (orange) and others (grey).

The Conservative formula has been based inter alia on a partisan press, Atlanticist foreign policy involving periodic military commitment, increasing Euroscepticism since Margaret Thatcher, free trade, low taxation, privatisation of government services, and emphasis on financial services in the south-east of the country as opposed to manufacturing industry in the north and west (apart from an arms industry that earned £14 billion in export revenues in 2018[ii]). Moreover, particularly under Tony Blair, New Labour (1997-2010) broadly embraced Conservative policies.

Jeremy Corbyn’s socialist politics thus represented an usual anomaly in U.K. politics – a genuine threat to the Conservative consensus on how to govern Britain, through a grassroots movement, albeit focused in the south of the country. The scale of the threat is demonstrated by Corbyn’s ability to attract almost as many votes to the Labour Party in the General Election of 2017 (c. 12.9 million) as Tony Blair did in his 1997 landslide victory (c. 13.5m).

The disturbing character of the campaign to defeat the Labour Party under Corbyn in 2019 has exposed the limits of democracy in the United Kingdom, and bears the fingerprints of Steve Bannon’s tactic of unsettling opponents by ‘deliberately crossing the line, defying normal courtesies, disrupting debate by scorning its conventions.’

The ‘Bannonisation’ of the Conservative Party: my @tortoise piece on the profound change triggered by Boris Johnson’s leadership – and the battle ahead for the party’s soul #CPC19 https://t.co/VhIiRtTAvl

— Matthew d'Ancona (@MatthewdAncona) September 28, 2019

- The Labour Party Bucks European Social Democratic Decline (to an extent).

Much has been made of the commonalities between Trump’s election and the Brexit referendum, but as the Polish writer Stefan Bielik observed ‘With its lurch to the right, Britain is no longer special in Europe.’[iii]

The relative decline in the fortunes in the British Labour Party can be placed in a broader European context, wherein a traditional ‘working class’ no longer support mainstream social democratic parties. In many cases this ‘blue collar’ constituency has shifted to Populist nationalist (or Nativist) parties, including Rassemblement National (formerly Front National) in France, Lega in Italy, and Alternative für Deutschland in Germany – although in many cases these parties adopt causes traditionally associated with the left.

Similarly, during the Brexit Referendum the Leave side made increased funding for the NHS a central plank of its campaign. The crucial distinction with socialism is that government services are envisioned as being restricted to the native population.

Brexit Bus Pledge, 2016.

Johnson’s proposal to build a bridge between Scotland and Northern Ireland also fits with the Populist, Bannonite formula. Post-Truth politics permit imaginative policies that barely consider logistical challenges or advantages, such as a wall the length of the U.S.-Mexican border, and as with Trump’s main policy proposal going into the last Presidential election, someone else would pay for it, in that case the Mexican government; whereas the EU is set to foot the bill for the bridge.

.@borisjohnson suggests a bridge between Northern Ireland and Scotland may eventually be built, saying 'watch this space' https://t.co/vghEPWSFGp pic.twitter.com/T5Z0P1PuV2

— ITV News (@itvnews) December 19, 2019

In the U.K. election of 2019, the Labour Party secured a 32% share of the electorate (or 10.2 million votes), which represented a significant decline on the 40% (12.9 million) received in 2017. That proportion, however, compares favourably with the fortunes of other mainstream European left-wing parties, especially when the success of Scottish and other national or regional parties is taken into account.

Among other large European countries, only in Spain did left-wing parties (Socialist Party and Podemos) secure a greater combined share of the vote than Labour in the U.K.. The steep decline of the German Social Democrats from 40% of the national share in 1998 to just 20% in 2017 might serve as a warning to those complacent enough to assume that Labour cannot sink any further.

Social democratic parties at beginning of century, beginning of decade & now (vote % in latest legislative election):

🇬🇧 43 35 32

🇩🇪 41 23 21

🇮🇹 42 33 19

🇫🇷 24 25 7

🇪🇸 38 44 28

🇵🇹 44 37 36

🇬🇷 42 44 8

🇸🇪 36 35 28

🇩🇰 36 26 26

🇫🇮 23 21 18

🇦🇹33 29 21

🇳🇱29 21 6

🇧🇪 20 21 16

🇮🇪 10 10 7— Neil Warner (@NeilWarner_) December 28, 2019

U.K. figures are skewed by a first-past-the-post electoral system that leads to tactical voting, and seriously diminishes opportunities for smaller parties. Nevertheless, at least by comparison with other European socialist parties, the U.K. Labour Party has emerged from Jeremy Corbyn’s tenure in relative good health, crucially, having retained its position as the second major party, it lives to fight another day.

The U.K. election in 2019 witnessed another poor performance from the Labour Party in Scotland. This decline stems from the 2015 election under Ed Milliband’s leadership, when the Party lost all but one of its seats. This election emphasises that Scotland is a political entity increasingly at odds with the rest of the United Kingdom, in which the Scottish Nationalist Party (S.N.P.) won forty-eight out of fifty-nine seats (with 45% of the vote); as in Northern Ireland, constitutional questions, including membership of the European Union and the United Kingdom are now deciding factors for the electorate.

In contrast, in Blair’s landslide victory, the Labour Party won fifty-six out of seventy-two seats there. Thus, the bald statement that this was Labour’s worst result since 1935 fails to take the altered politics of Scotland into account.

Vitally, Labour under Corbyn fought off the Liberal Democrat attempt to assume the mantle of challenger to the Conservative Pary, and potential extinction in an unforgiving first-past-post-system. An early surge in Lib-Dem support saw them surpass Labour (23% v. 21%) in at least one poll prior to the election at the end of September.[iv] The party had become a refuge for both disaffected Labour politicians (including Chuka Umunna and Alastair Campbell), and claimed support from Conservative grandees such as John Major and Michael Heseltine.

In the election itself, however, Liberal-Democrat support fell away to just under 12% of the total – an improvement on 2017 when the party won just 8% of the total – but a massive disappointment nonetheless considering their high hopes of becoming the main party of opposition, especially through favourable coverage in the pro-Remain The Guardian.

It might have been expected that in an election in which the Conservative Party put Brexit front and central that the only U.K.-wide party fully committed to remaining in the European Union would emerge as the main challenger. But this re-running of the referendum did not materialise.

Again bearing in mind the unrepresentative, and arguably anti-democratic, nature of the first-past-the-post system, a socialist message, articulated by Jeremy Corbyn, appears to remain a vote winner – at least among those opposed to the Conservative Party – by comparison to the centrist liberal platform; with many voters also aware that the Liberal-Democrats had entered into a coalition government with the Conservatives between 2010 and 2015 that implemented austerity economic policies.

Thus, reasserting a centrist, Blairite approach, including a swift return to the European Union, does not seem a likely formula for a Labour Party revival unless its policies cleave closely to the Conservative consensus to a point where the electorate is indifferent to the outcome: as under New Labour when voter turnout dipped below 60% in 2001, compared to 68% in 2017 and 66.5% in 2019.

- Unequivocal Brexit Policy Proved Crucial to Conservative Victory.

It is widely assumed – with the former BBC Newsnight journalist Paul Mason a prominent advocate of this view[v] – that Jeremy Corbyn’s unwillingness to make a firm commitment to remaining within the European Union was the Labour Party’s undoing. The argument runs that had Corbyn campaigned with a defiant promise for a yes vote, perhaps in alliance with the Liberal-Democrats, he would have carried the day. But this flies in the face of the reality.

After years of bickering inside Parliament, leading to the infamous proroguing, and courtroom battles, it would appear that serious Brexit fatigue had set in among the electorate. The Conservative pledge ‘To Get Brexit Done’, repeated at every possible juncture throughout the campaign with admirable unity of purpose, proved an unbeatable platform – helped of course by an overwhelmingly supportive media, increasingly hysterical in its opposition to Corbyn.

Boris Johnson drove a 'Get Brexit Done' branded JCB through a polystyrene wall that said 'Gridlock'.

The question is at this late stage of the campaign, will this subtle message cut through to ordinary voters? pic.twitter.com/zvS0kx388Q

— Oliver Milne (@OliverMilne) December 10, 2019

Even Remain-voting Conservatives seem to have been attracted by the simplicity of the message, albeit the claim that a vote for the Liberal-Democrats could bring Corbyn to power may also have proved effective. More importantly, the Conservatives exploited an enduring grievance that the democratic will of the people, as expressed in the Referendum of 2016, was being ignored by a political elite – an argument that resonated strongly in Brexit-voting parts of the country: Labour’s so-called ‘red wall.’

The vast majority of Labour’s losses to the Conservatives came in those Brexit-voting constituencies of the North, Midlands and Wales,[vi] many of which elected Conservative MPs for the first time in decades.

Constituencies lost by Labour to Conservatives: Blyth Valley; Workington; Wrexham; Leigh; West Bromwich West; West Bromwich East; Bishop Auckland; Don Valley; Wakefield; Rother Valley; Kensington; Newcastle-under-Lyme; Bolsover; Bolton North East; Bury North; Bury South; Heywood & Middleton; Sedgefield; Warrington South; High Peak; Penistone & Stocksbridge; Scunthorpe; Great Grimsby; Redcar; Burnley; Bassetlaw; Stoke-on-Trent North; Stoke-on-Trent Central; Wolverhampton North East; Wolverhampton South West; Blackpool South; Hyndburn; Vale of Clwyd; Clwyd South; Delyn; Peterborough; Durham North West; Birmingham Northfield; Barrow and Furness; Darlingon; Keighley; Colne Valley; Dewsbury; Ashfield; Lincoln; Gedling; Derby North; Dudley North; Ipswich; Stroud; Crewe & Nantwich; Bridgend; Ynys Mon; Stockton South.

Tory candidate for Ashfield, Lee Anderson, calling for the creation of forced labour camps.

In the last election Tories were 1% behind so he has a strong prospect of becoming an MP.#GE2019#forcedlabourcamps pic.twitter.com/z1E0AGJrpO

— Oliver Price (@olivertimprice) November 19, 2019

All of these constituencies, bar Stroud in Gloucestershire, Kensington in London and Ipswich in Norfolk, are in the North of England or Wales – Labour’s traditional industrial heartland.

This emphasises the extent to which Brexit dictated the electoral outcome, especially given Labour retained seats in those same constituencies in 2017 with a manifesto promising to respect the result of the referendum.

Thus, while opinion polls register distaste for the Labour leadership among the electorate, after a sustained campaign of vilification in the press, this cannot be separated from the substance of policies (particularly indecisiveness over Brexit), as the opinion questionnaire purports to.

We asked voters why they had not voted for particular parties in our on the day poll (12th December). For Labour the key issue was the leadership. pic.twitter.com/pu7iBWDp94

— Opinium (@OpiniumResearch) December 13, 2019

Thus, both David Broder[viii] and Owen Jones[ix] have persuasively argued that Labour’s failure to replicate its Brexit policy from the 2017 election was its undoing. Labour certainly lost votes and even seats to the Lib-Dems and S.N.P. in 2019, but these parties would probably have supported a minority Labour government which promised to re-run the referendum.

Jeremy Corbyn can certainly be faulted for adopting what appears to have been a principled neutrality on the question of Brexit, but perhaps it was the decision of his leading lieutenant John McDonnell to advocate for another referendum and a Remain vote – contrary to the Bennite anti-EU tradition within the Labour Party to which he belonged – that was the real problem; indeed, revealingly, McDonnell has ‘owned’ the electoral disaster.[x]

It may plausibly be argued that the stubborn refusal of many within Britain – and without – to accept the clear verdict of the British people on membership of the European Union, however sinister the tactics of the Leave side, permitted the political gambler and serial liar that is Boris Johnson to win the U.K General Election of 2019, by a handsome margin.

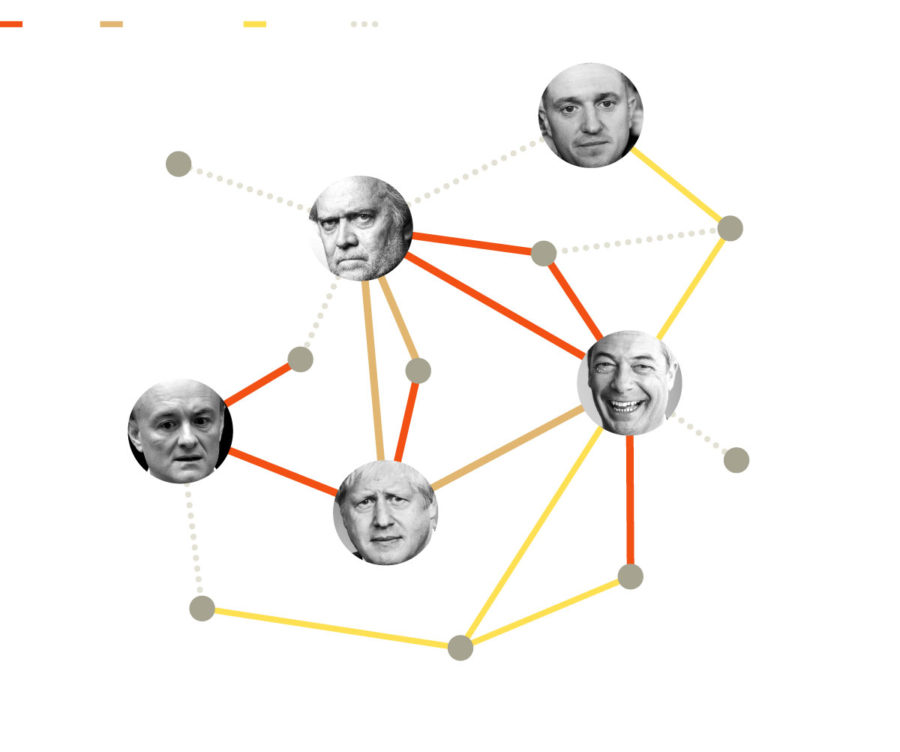

- ‘Make Hodge-Podge of Everything’

Source: Matthew D’Ancona, ‘Bannon’s Britain’ The Tortoise, September 28th, 2019, https://members.tortoisemedia.com/2019/09/28/bannons-britain/content.html?sig=H8jSG1aWM202Udsw0YK9FImq6JLIDJ0W8yroue9l5hc

According to Matthew D’Ancona there ‘really is no way to understand how radically’ Boris Johson is ‘trying to remould the Conservative Party, and the very specific way in which he is framing contemporary political debate, without reference to the self-appointed father figure of the worldwide right-wing nationalist movement.’

2019 marked a new low in British democracy, as fake and misleading information became central to the Conservative Party’s campaign of undermining its opponents, in particular Jeremy Corbyn. The Labour Party for the most part, fought a clean fight, essentially winning the campaign on the relatively free medium of Twitter,[xi] where organic sharing is rewarded above political advertisements.

Conservative Party distortion began in earnest during the first leaders’ debate, when its press office temporarily changed the name on its official Twitter handle to ‘FactCheckUK’, implying it was an independent fact-checking source. That the Party was prepared to do so given the near certainty of discovery is indicative of the cynicism of Post-Truth contemporary political campaigning. Under the guidance of Steve Bannon, who masterminded Donald Trump’s victory, Populists bend reality and impugn the motives of all politicians.

Thus, Adam Ramsay describes the Conservative strategy as being to: ‘wage war on the political process, on trust, and on truth.’ The Hobbesian project ensures ‘the whole experience is miserable, bewildering and stressful.’ All that remains is to ‘ask voters to make it go away.’[xii]

Renowned Nazi sympathiser @tnewtondunn has been caught out editing his own Wikipedia page to remove evidence of the time he used neo-Nazi resources as a source for his far-right hit piece on @jeremycorbyn. #dontbuythesun pic.twitter.com/f0VEhs3KpC

— McCats (@PeteMcCats) December 20, 2019

Although those with an interest in politics tend to gravitate towards Twitter, Facebook actually has three times as many daily visits in the U.K.,[xiii] and as the Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed, users of the platform are susceptible to sophisticated propaganda, and political ads are not verified.

Independent analysis found an extraordinary 88% of Conservative ads on Facebook contained misleading information; by comparison 0% of Labour’s ads had fake news.[xiv] The influence of such propaganda on individuals who do not ordinarily take an interest in politics cannot be underestimated.

Moreover, the Conservative Party raised more than three times as much as Labour in large donations (over £7,500) over the course of the campaign (£18 million compared to £5 million), providing them with ample resources for online campaigns targeting key marginal constituencies.

Added to this, the Conservative Party retained partisan support from most of the widest circulating newspapers in the country, including The Daily Telegraph, The Daily Express, The Daily Mail, The Times and The Sun. Only The Daily Mirror was demonstrably supportive of Labour.

Left-leaning or liberal broadsheets, The Guardian and The Independent were generally opposed to the Conservatives, but tended to be at least as supportive of the Liberal Democrats as Labour, and ran stories damaging to the latter, including unsubstantiated allegations of antisemitism against Jeremy Corbyn.[xv]

Thus, The Guardian carried a letter, signed by the novelist John le Carré and others, in which the authors claimed antisemitism concerns around Corbyn would prevent them from voting Labour.[xvi]

The Guardian also ran a damaging opinion piece by the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore in which he amplified these claims. He made great play on Corbyn’s unsatisfactory responses to aggressive questioning by Andrew Neil (whose formidable inquisitorial skills Boris Johnson refused to be subjected to) in which the interviewer demanded that Corbyn condemn the proposition that Rothschild Zionists were controlling world governments. Montefiore also referred to the Labour leader’s 2012 support of a grafitti artist’s work apparently featuring antisemitic tropes, in what was an article strikingly thin on substantive evidence for a damaging allegation.[xvii]

In a Facebook post in 2012, Corbyn offered his backing to Los Angeles-based street artist Mear One, before subsequently conceding he was wrong to support the graffiti artist.

Alongside criticisms of Corbyn by leading cultural figures in the liberal media, in an unprecedented move, the Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis wrote an article for The Times[xviii] arguing Corbyn was unfit to be Prime Minister.

Notably, antisemitism charges were hardly leveled against Corbyn prior to the 2017 election. The extent of the campaign running up to the 2019 elections suggests a coordinated, prolonged strategy, designed to impugn the reputation of a long-term anti-racist campaigner in Jeremy Corbyn, just as Arthur Scargill’s reputation was smeared at the height of the miners’ strike.

‘Good luck Jeremy…you’re better than them. Nice one’

This gent explains, in 60 seconds, why the establishment attacks @jeremycorbyn #ge2019

— Aaron Bastani (@AaronBastani) November 29, 2019

This represented another feature of the Bannonite undermining of the political process, whereby all politicians are depicted as being racist or immoral. Indeed, Boris Johnson could hardly escape such censure given his descriptions of picaninnies with water melon smiles, women in burkhas looking like letterboxes, and homosexuals being tank-topped bum-boys.[xix]

The episode recalls Fyodor Dostoyevksy’s 1872 Devils, towards the end of which the conspirators Lyamshin is put on trial and asked, ‘Why so many murders, scandals and outrages committed?’ to which he responds that it was to promote:

the systematic destruction of society and all its principles; to demoralise everyone and make hodge-podge of everything, and then, when society was on the point of collapse – sick, depressed, cynical and sceptical, but still with a perpetual desire for some kind of guiding principle and for self-preservation – suddenly to gain control of it.[xx]

- The BBC is no longer a guardian of British democracy (if it ever was).

Considering the distinct disadvantages that the Labour Party laboured under during this election, with traditional media and fake Facebook ads ranged against it, British democracy was reliant on the BBC to provide a measure of balance. Alas, the public service broadcaster not only failed to vindicate its public service mandate, but actively participated in the fake news campaign in support of the Conservative Party. It was left to Channel 4 to provide meaningful criticism of the Conservatives on the television.

The BBC’s subtle falsification of news content began early in the campaign with the use of archive footage from 2016 of a dignified Boris Johnson as Foreign Secretary laying a wreath outside the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday – in place of actual footage of a dishevelled Boris Johnson making a mess of placing a wreath at the ceremony in 2019.

There followed the doctoring of a video in which laughter greets Boris Johnson’s claim that he always told the truth, which was used in subsequent news bulletins.

These were blatant examples of bias. Much of the content was not overtly opposed to Labour, however, but subtly reinforced key Conservative messages, especially through reports from Political Editor Laura Kuenssberg.[xxi] Characteristically, far greater prominence was given to the obscure Labour MP Ian Austin’s endorsement of the Conservatives compared to the ‘Big Beast’ Ken Clarke’s defection.[xxii]

As Peter Oborne pointed out in a stinging critique, the BBC tends to be biased in favour of any sitting governments, but the level of duplicity of 2019 is unprecedented in recent history. The broadcaster reverted to depicting a general lowering in political standards, encompassing the Labour Party and presumably itself. Thus on the night before the election Radio 4 broadcast a montage of moments seemingly aimed to make the point that all the protagonists were misleading voters.[xxiii]

The conduct of the national broadcaster reflects the radical challenge posed by Corbyn and his team to the ruling Conservative consensus.

Jeremy Corbyn took the U.K. establishment by surprise during the 2017 Election campaign, coming within a whisker of victory. This would have had serious ramifications for the domestic economy, but perhaps more importantly also U.K. foreign policy, and the arms’ industry, both in the U.K. and the wider military industrial complex in the U.S., in particular.

It is unsurprising, therefore, then that a sophisticated and well organised campaign involving elements within both the BBC and other liberal media should have been deployed to undermine Corbyn and his politics.

has a single #bbcnews journalist resigned in protest over having been asked to become an essentially a State News Agency, & smearing the opposition so as to bring an extreme right-wing, racist government into power? Even one?

— David Graeber (@davidgraeber) December 17, 2019

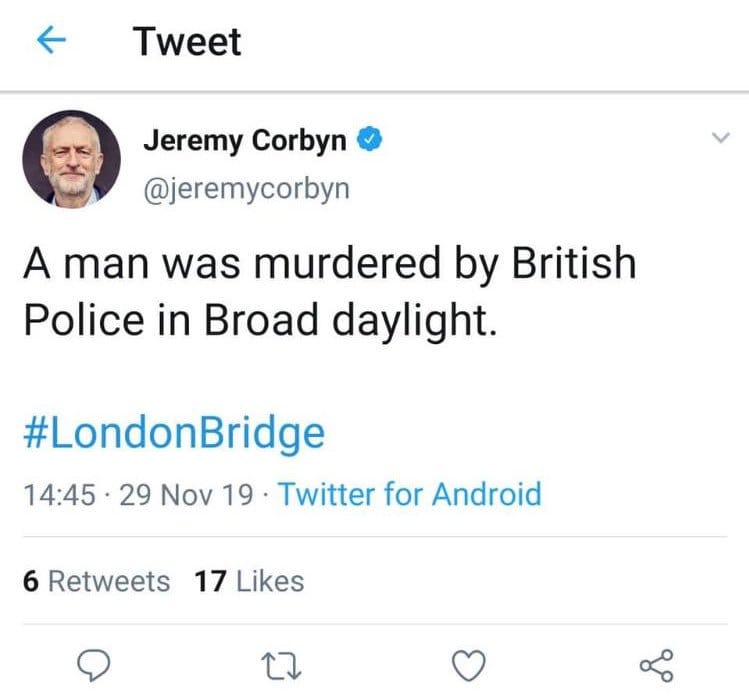

Finally, conspiracy theories are just that, but it is perhaps notable that the London Bridge stabbings was the only so-called ‘terrorist’ attack that has occurred on U.K. soil since, again suspiciously, the spate of attacks preceding the 2017 election.

We have no evidence of provocateurs in action – as during a CND protest that occurs in Chris Mullin’s 1982 novel A Very British Coup – but the febrile atmosphere generated by hysterical media in the wake of any terrorist attack is certainly advantageous to a Conservative Party long associated with law and order – especially when confronted by a Labour leader, who previously welcomed former terrorists into the political fold.

Notably, within hours of the attack a screenshot of a fake tweet, depicting the Labour leader as unsupportive of the police response, easily shared via WhatsApp, emerged.

Fake Jeremy Corbyn Tweet that appeared soon after the attack.

- ‘Corbynism’ has shifted the mainstream of British Politics to the left, but socialism still needs a makeover.

Jeremy Corbyn is now a lame duck Labour leader, while the Party considers a replacement. His generation of Bennites, who remained true to socialist and pacifist principles throughout the long period of New Labour centrism under Tony Blair, have, almost miraculously, seized the opportunity to define the philosophy of the Party for the forthcoming decades. This maintains the threat to the ruling Conservative consensus operating since World War II, notwithstanding Boris Johnson’s ‘thumping’ majority.

The ranks of the Labour Party swelled to over half million under Corbyn, having stood at barely two hundred thousand while Ed Milliband was at the helm.[xxiv] Exceeding Conservative Party membership by three hundred thousand, it is among the most formidable, and youthful, left-wing parties in the developed world, and the largest of its kind in Europe.

Moreover, running parallel to the Party is the campaigning Momentum movement, with forty thousand members. Any prospective Labour leader must now appeal to this young radical constituency. An immediate reversion to a centrist Blairite leader is an impossibility, and moreover is unlikely to be well received by an electorate in the grip of Bannonite Populism.

‘Corbynism,’ such as it is, is often derided as a middle class and metropolitan phenomenon. This is considered a structural weakness of most social democratic parties around the world. It ignores, however, the shifting dynamics of altered economies, as those once considered middle class are squeezed increasingly by high property prices and diminishing opportunities in careers such as education and the arts.

It should also be born in mind that crippling poverty, afflicting a majority of the population, generated socialism at the end of the nineteenth century. Even for much of the twentieth century, a considerable proportion of the population was actually malnourished, whereas today the poor are more likely to be obese. Notwithstanding the food banks that emerged during the Cameron era of austerity, the extreme poverty that engendered socialism has largely been eliminated.

Ironically, the tangible gains socialism brought to Britain and other European societies in providing for cheap food, accommodation, education and healthcare now actually work to the benefit of Populists that prey on consumer and entrepreneurial aspirations, while incubating a fear of an imminent immigrant ‘other’ destined to appropriate indigenous welfare, educational and healthcare entitlements.

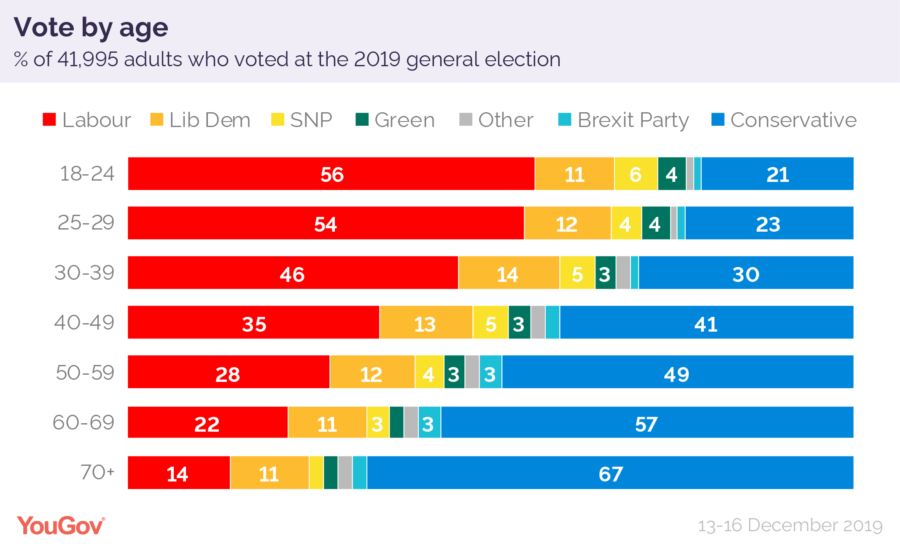

Unlike their older peers, young people across the U.K. were, however, disproportionately attracted to a Labour Party led by Jeremy Corbyn,[xxv] including principled opposition to militarism, a Green New Deal and effective redistribution of wealth, including inter-generational transfer. This reveals a growing awareness that high capitalism has brought unprecedented inequality and rampant corporate control, requiring decisive state intervention. This should provide the impetus for a reconceived socialism that merges an aspiration to raise human welfare with the environmental and anti-war movements.

Source: YouGov: https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/12/17/how-britain-voted-2019-general-election

It should also be conceded that the Labour campaign’s robust defence of the NHS against privatisation, and outside interference, has probably ensured the Conservatives will maintain public health services, at least to British citizens, for the time being. Thus, in defeating Corbynism the Conservative Party has been forced to adopt policies that many among its ranks do not support.

The Conservatives now have unanimity on Brexit, but it remains to be seen how long a Party prone to factionalism will hold together, especially after absorbing Populist Brexiters. This will provide opportunities for Labour to chip away at the Conservative consensus.

A priority for the Labour Party will be to develop policies to defeat the Conservative Party in the North of England and Wales. With Brexit ‘done’ the Conservative hold over the ‘red wall’ seems fragile, especially with younger people preferring Labour, and Conservative supporters dying out. Ongoing wrangling with the E.U. could cause serious economic damage, including to manufacturing industries in the North, which the Conservatives will surely be held responsible for.

Hearteningly, the idealism of the Corbyn years has provided a learning ground for a generation of activists, now attuned to the difficulty of challenging the Conservative consensus. There are genuine grounds for optimism that a new generation of tech savvy activists can ultimately defeat Bannonite Populism, and lay the political and economic foundations for a carbon neutral New Jerusalem. But the dominant Conservative faction will, as ever, be difficult to shift, especially in the current atmosphere of Post-Truth, and attendant disillusionment with the political process.

To lay the foundations for a New Jerusalem it is incumbent upon the Labour Party to redefine the socialist project, accommodate entrepreneurial innovation – with the mantra that ‘small is beautiful’ – and avoid the bureaucratisation that was a hallmark of New Labour under Blair and Brown.

Labour can, and should, offer principled opposition to the enormous corporations, including Facebook, whose interests the Conservative Party has long served, and which New Labour in its giddy appreciation of business leaders also embraced.

A moral obligation to address the poverty and inequality, still strikingly evident throughout the U.K., should be accompanied by an appeal to small business people. The message that eradicating poverty and reducing inequality serves entrepreneurship should be made loud and clear: an impoverished population cannot sustain new ventures. Thus, the Labour Party may appeal to a nation of shopkeepers, selling new and environmentally friendly innovations, and no longer reliant on dark satanic mills that loom across post-Industrial Britain, fueling a Populist right.

Follow Frank Armstrong on Twitter: @frankarmstrong2

[i] Dr Bart Cammaerts, Brooks DeCillia, João Carlos Magalhães, Dr Cesar Jimenez Martinez, ‘Journalistic Representations of Jeremy Corbyn in the British Press’, LSE, 2016, http://www.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/research/research-projects/representations-of-jeremy-corbyn

[ii] Dan Sabbagh, ‘UK reclaims place as world’s second largest arms exporter’, The Guardian, July 30th , 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jul/30/uk-reclaims-place-as-worlds-second-largest-arms-exporter

[iii] Stefan Bielik ‘With its lurch to the right, Britain is no longer special in Europe’, The Guardian, December 24th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/24/lurch-right-britain-special-europe-authoritarian

[iv] Gus Carter, ‘Lib Dems overtake Labour in latest poll’ Metro, September 19th, 2019,

[v] Paul Mason, ‘AFTER CORBYNISMWHERE NEXT FOR LABOUR’, paulmason.org, December 16th, 2019, https://www.paulmason.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/After-Corbynism-v1.4.pdf

[vi] Paula Surridge, ‘Labour lost its leavers while Tory remainers stayed loyal’, The Guardian, December 13th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/13/conservatives-bridge-brexit-divide-tory-landslide

[viii] David Broder, ‘Labour’s Brexit Stance Defeated Corbynism Months Ago’, December 16th, 2019, The Jacobin, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/12/labour-party-uk-brexit-jeremy-corbyn-general-election

[ix] Owen Jones, ‘Brexit and self-inflicted errors buried Labour in this election’, The Guardian, December 19th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/18/brexit-labour-election-corbyn-left

[x] Rowen Mason, ‘’I own this disaster’: John McDonnell tries to shield Corbyn’, December 15th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/dec/15/i-own-this-disaster-john-mcdonnell-tries-to-shield-corbyn-rebecca-long-bailey.

[xi] Annabelle Timsit, ‘The UK election result shows why Twitter does not speak for most voters’, Quartz, December 13th, 2019, https://qz.com/1767195/uk-election-result-shows-twitter-doesnt-speak-for-most-voters/.

[xii] Adam Ramsay, ‘Boris Johnson made politics awful, then asked people to vote it away’, Open Democracy, 22nd of December, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/boris-johnson-made-politics-awful-then-asked-people-vote-it-away/.

[xiii] S. O’Dea, ‘Leading social networks by share of website visits* in the United Kingdom (UK) as of June 2019’, Statista, September 3rd, 2019, https://www.statista.com/statistics/280295/market-share-held-by-the-leading-social-networks-in-the-united-kingdom-uk/.

[xiv] Rupert Evelyn, ‘88% of Conservative ads on Facebook ‘misleading’’, ITV News, December 6th, 2019, https://www.itv.com/news/2019-12-06/88-of-conservative-ads-on-facebook-misleading/.

[xv] Letter: ‘Jeremy Corbyn’s refusal to apologise for antisemitism proves he is unfit to be prime minister’ Independent, November 27th, 2019, https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/letters/jeremy-corbyn-antisemitism-labour-andrew-neil-interview-chief-rabbi-election-a9220576.html.

[xvi] Letters, ‘Concerns about antisemitism mean we cannot vote Labour’, The Guardian, November 14th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/14/concerns-about-antisemitism-mean-we-cannot-vote-labour.

[xvii] Simon Sebag Montefiore, ‘This antisemitism poisons any good Labour might do’, The Guardian, November 30th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/nov/30/antisemitism-poisons-any-good-labour-doing-simon-sebag-montefiore.

[xviii] Ephraim Mirvis, ‘Ephraim Mirvis: What will become of Jews in Britain if Labour forms the next government?’ The Times, November 25th, 2019, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/edition/news/ephraim-mirvis-what-will-become-of-jews-in-britain-if-labour-forms-the-next-government-ghpsdbljk.

[xix] Adam Bienkov, ‘Boris Johnson called gay men ‘tank-topped bumboys’ and black people ‘piccaninnies’ with ‘watermelon smiles’’, Business Insider, November 22nd, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/boris-johnson-record-sexist-homophobic-and-racist-comments-bumboys-piccaninnies-2019-6?r=US&IR=T.

[xx] Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Devils, (translated by Michael R. Katz), Oxford, 1999, p.748.

[xxi] Untitled, ‘BBC caught in the crossfire: why the UK’s public broadcaster is becoming a big election story’, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/bbc-caught-in-the-crossfire-why-the-uks-public-broadcaster-is-becoming-a-big-election-story-128639.

[xxii] Peter Oborne, ‘In its election coverage, the BBC has let down the people who believe in it’, The Guardian, December 3rd, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/dec/03/election-coverage-bbc-tories.

[xxiii] Ramsay, 22nd of December, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/boris-johnson-made-politics-awful-then-asked-people-vote-it-away/.

[xxiv] Rowena Mason, ‘Labour membership falls slightly but remains above 500,000’, The Guardian, August 8th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/aug/08/labour-membership-falls-slightly-but-remains-about-500000.

[xxv] Adam McDowell and Chris Curtis, ‘How Britain voted in the 2019 general election’, YouGov, December 17th, 2019, https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/12/17/how-britain-voted-2019-general-election.