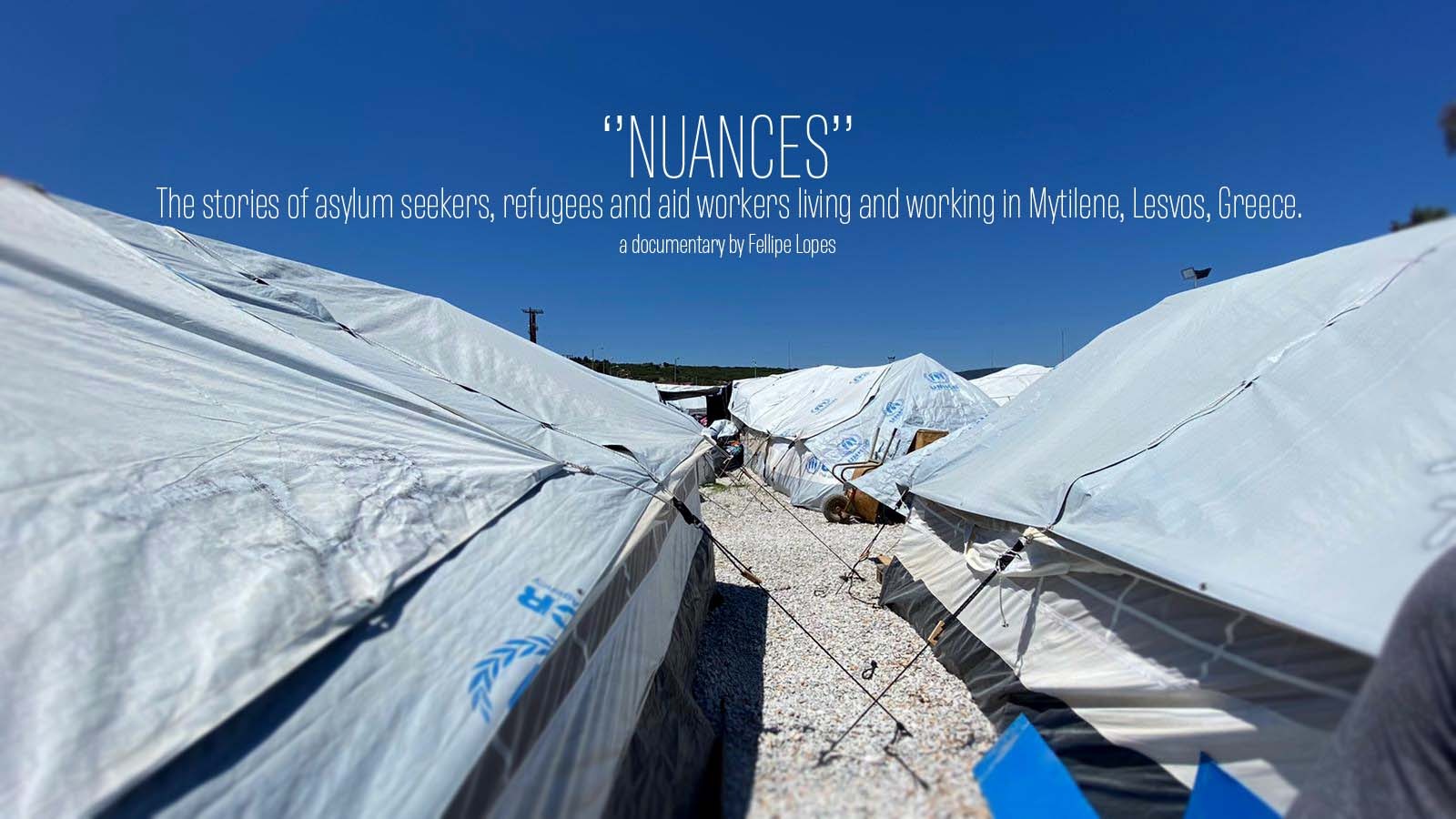

“Nuances” is a work in progress by South American documentary maker Fellipe Lopes. Since May 2021, Lopes has been on the ground in some of the most notorious refugee camps in Europe, on the Greek island of Lesvos (Lesbos), just off the coast of Turkey.

"At one point a guy passed five metres away from me with a machete, a massive knife, and I heard the noise of stabbing."

Report from @fellipelopes7 inside Camp #moria, Lesboshttps://t.co/SG7JB7k4Gq@CaoimheButterly @IrishRefugeeCo @openarms_found @RefugeeRescueUK @seawatch_intl— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 26, 2020

“Nuances” seeks to understand the ‘refugee crisis’ from the perspective of asylum seekers and refugees, and their relationship with humanitarian workers and volunteers living and working on the island. Lopes is soon to finish the interviews and the recording of the documentary. Until now, Lopes has been working voluntarily, at his own expense. He has now started a Kickstarter to crowdsource €7,000 for the next stage of the project, including post production and distribution.

Last month, Lopes was nominated for the Irish Red Cross Humanitarian Awards for Journalism Excellence. In the same month, Cassandra Voices journalist Daniele Idini had the chance to catch up with the documentary maker.

Fellipe Lopes by Daniele Idini

Daniele Idini (DI): How long have you been in Lesvos now and what’s the situation like?

Fellipe Lopes (FL): So I have been in Lesvos for the last six months and working on this documentary since I arrived. This documentary is a collection of interviews with asylum seekers, refugees, migrants explaining the challenges they are facing. It seems like they basically have only one option when it comes to work, which is basically to work as an interpreter. And this is not something that makes all the migrants and refugees happy because they are revisiting all the trauma through other people’s experience.

DI: So basically, you are saying this work is, in a way, necessary for the camp’s operation, but is, in a way, preventing migrants from escaping the camp’s system,.

FL: Exactly. These migrants are well suited to this kind of work, because they often speak the necessary languages – it might be Farsi, or Arabic, Lingala or French. They also can understand the struggles other refugees have been through, having experienced similar things themselves. On the other hand, however, they have ended up working in the humanitarian sector when they actually need humanitarian support.

This is one of the topics covered in the documentary. Another issue, is the kind of social and legal challenges humanitarian workers are facing here. It’s about the authorities. The role of the police force and the army in regards to upholding the right of media coverage.

A Greek activist was invited to receive an award for his role in saving refugees but received a late phone call one night saying it had been withdrawn. This article explains whyhttps://t.co/wzRsMVIcAM

Image @fellipelopes7 @CaoimheButterly @broadsheet_ie @soundmigration @Elzobub— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 28, 2021

The documentary is set with the island of Lesvos, and its capital Myteline, in the background. But the documentary centres on the stories that happen inside the camp, stories that happens outside of the camp, and the reasons and motivations for those asylum seekers coming to Greece. And as well, we have a really interesting part of the documentary that examines the pushback happening here in the Aegean Sea, which divides Turkey and Greece.

We have a lawyer who’s been working around issues related to pushbacks for the last five years. We also have a German journalist who’s been covering all the pushbacks as well for the last three years. Obviously, the situation in Lesbos is so dynamic and things are changing rapidly. It’s been really challenging for me to keep up with this story. Things have moved so fast, and that’s maybe the reason I’m still here, and will stay a little bit longer, because these are stories that are developing.

The dynamics in the camps are changing, which is new. They call this the new camp, which is where they’re trying to reduce the number of asylum seekers. Since the fire that happened last year, the government promised to build a new camp. But this never happened, basically because the local community are against new camps in the area. As a result, the temporary camps have become the de facto new camp.

DI: So your documentary also tackles the relationship between the refugee camps and the local community?

FL: Yes. I spoke with locals. Some are understanding of the necessity for a new camp. With that said, whether there is a new one or not, there are still 3,000 migrants on the island awaiting resolution of their cases. – building a new camp won’t solve the problem. they need to be processed

Obviously, the freedom of these people is highly restricted.

In the end, everything goes back to the camp. It isn’t a liveable reality. There are no schools in the camp and there’s only precarious legal and medical support.

Last week, a woman passed away inside of the camp, for example. This is the reality that is happening in Lesvos. And everybody expects another massive wave of asylum seekers coming to Greece due to the situation in Afghanistan. Less and less will reach the Greek shore, however, because of the increased activity of the Greek coastguard and the European Frontex.

Demonstration in support to Afghanistan.

DI: Why should the general public support the making of this documentary?

FL: It’s an overview of a situation that’s happening in Europe; it’s happening in Greece, through Greek laws, through the Greek system. But there are comparable problems in terms of the pushback between Bosnia and Croatia. The same thing is happening between Belarus and Poland. The same thing is happening in the Mediterranean Sea, between Libya and Italy, in Libya itself, and in Spain.

This documentary shows that there is still a massive flood of refugees coming to Europe and obviously the policies in place are not facilitating those asylum seekers to claim asylum in Greece. This documentary is set in Lesvos, but it records something that is happening throughout Europe’s borders.

People keep using this term a ‘refugee crisis’. This is a mistake. More than a refugee crisis, there is a policy crisis.

What we’re witnessing is a series of legal decisions that are impacting the lives of those who are exercising a right to apply for asylum in Europe. These people are not criminals. The Geneva Convention guarantees them a right to apply for asylum. But this right is not being upheld properly. People are waiting one, two, three, or even over five years to have their claims processed.

Interview edited for brevity and clarity by Ben Pantrey.