Photographer Daniele Idini travelled from North to South of Italy and discovered a country in severe economic crisis desperate to resume the good life.

On July 8th I landed in Malpensa (Milan) on a half-empty Ryanair flight from Dublin. It is the largest airport in Italy, located about forty kilometres from the city of Milan.

I’ve known this airport since its inception, having grown up just two kilometres away. Over the past few years, while living abroad, more often than not it has been the first destination on my visits home. I was not surprised to see it so empty considering the circumstances, but still, I cannot deny the unease I felt walking along its silent corridors.

On a Ryanair flight

At the passport control there was a table in the middle of the exit corridor filled with mandatory forms that all passengers are obliged to fill in. These certify that you are currently not under a mandatory quarantine due to Covid19, and ask for reasons for your travel.

After a temperature scan, a border guard asked where I was flying from.

“Dublin,” I replied.

“And before that?” he replied.

“Dublin” I asserted

“Ok move along,” he said.

And that was that.

Milan, Malpensa Airport, July 2020

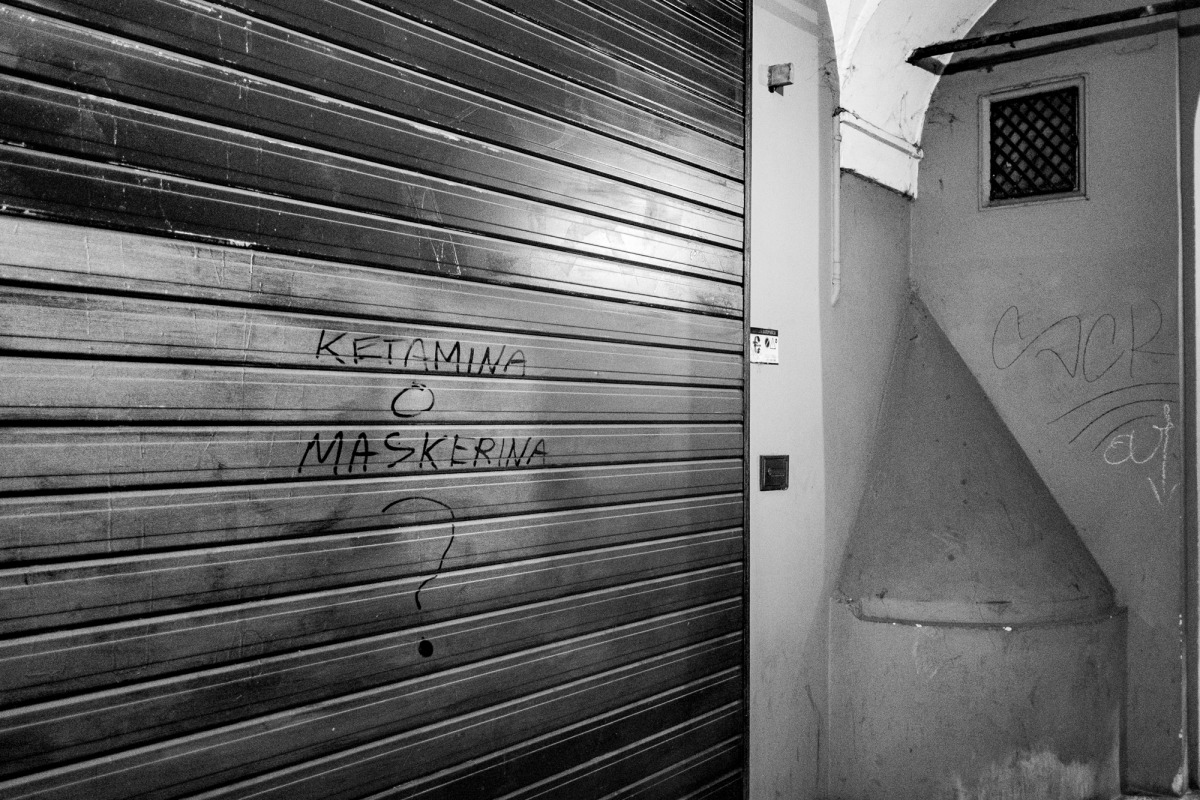

Across Italy face masks are mandatory in all indoor public spaces, as well as some outdoor locations where social distancing is difficult to practice such as outdoor markets, busy city centres and the like. Compliance is generally high throughout the country, with many wearing them even where it is not mandated, but clearly in the north – in the regions that have borne the brunt of the pandemic – compliance is more evident.

Tuesday’s market in Arona, northern Italy on July 2020.

Wearing a mask – which is compulsory in many parts of the world at this stage – is widely regarded as a symbol of solidarity or just to communicate that you care. In Italy it is often to be seen hanging off a person’s chin, or only covering the mouth but not the nose. It is commonly worn above the elbow, ready for use when the need arises. It is hard to see how it is really providing much protection against contagion, apart from in clinical settings where it is worn by trained professionals.

Rome bus, on July 2020.

The widespread message is that if you care you wear one as much as you can. Alas, if you care you cannot have close contact with your grandparents either, even after months of living at a distance.

Morning in Bologna, on July 2020.

On the Road

After spending time in the north I moved south towards the mezzogiorno, driving all the way to the tip of Italy from where I took a ferry to Sicily, stopping briefly along the route in Bologna, Orvieto, Naples, Pizzo Calabro and on the way back in Rome.

While crossing the Strait of Messina, Southern Italy, on July 2020.

The pictures that are featured in this article are nothing more than snapshots, offering a view of the ripples on the surface of a new reality, in which we are all involved, in some way or another, in trying to come to terms with.

While crossing the Strait of Messina, Southern Italy, on July 2020.

A few hours is obviously insufficient to grasp the actual situation in each place: definitely not in a country like Italy where variety and internal differences are determining characteristics. Nor is it easy to convey how the many people facing different realities that I encountered are coping in different ways with the obvious trauma of a very strict lockdown, and the unprecedented economic uncertainty that lies head.

Vicolungo Outlet Village, Piedmont, Northern Italy, on July 2020.

Monthly Market in the small town of Giarratana, Southern Sicily, on July 2020.

Nonetheless, I noticed common traits running through both north and south, region by region. One thing was definitely apparent: in addition to the collective trauma and the aftermath of the lockdown, I found a country struggling to cope, on the one hand with a lack of clarity about the present and the experience of the last few months; and on the other an absolute inability to forecast anything any longer. Our hard won, mainly technologically induced ability to predict the future, has gone out the window at every level of society, of our economy, and right down to the basic level of our lives.

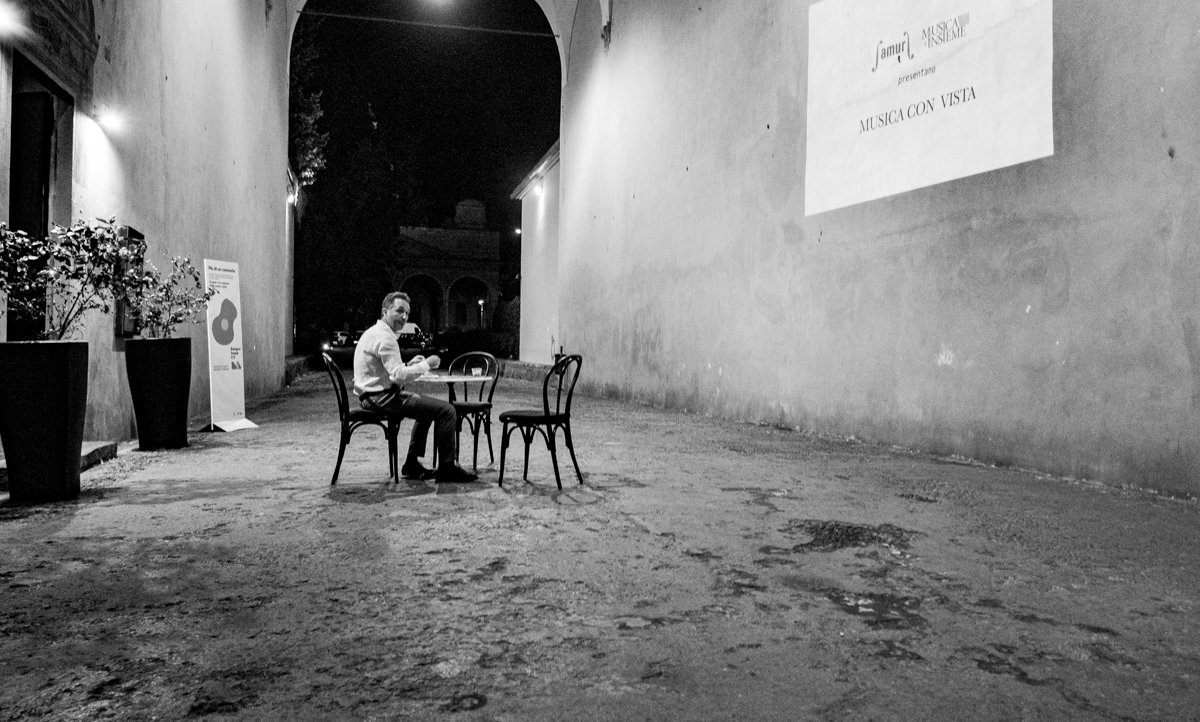

Infinity Café, Bologna, on July 2020.

How many employees should one medium-sized factory rehire after the lockdown to recover? What will the demand be for certain local products over the next few months? Will tourism recover next year, or ever? What about Christmas this year? How long will the redundancy package last for, and when will the actual payment arrive.

Bologna’s city center, on July 2020.

The majority of laid-off workers I spoke to, or know, by the month of July had only just received the emergency payment for the months of March or April. How long are personal savings supposed to last in those households that are lucky enough to hold them? What about the hundreds of thousands that are working in the so-called black economy for which no safety net exists at all? They are now dependent on what savings they have, if any; meanwhile charities are overwhelmed by requests for help, as loan sharks circle.

Rome, on July 2020.

The impossibility of forecasting demand stretches into a future strewn with unforeseeable and seemingly insurmountable challenges. This disproportionately affects (as always) small and medium-sized businesses, which live under the constant threat of another lockdown; an eventuality that many fear will be the final nail in their coffins.

Street market of Porta Portese in Rome, on July 2020.

The resultant anxiety and irrational behaviours seem like withdrawal symptoms from our contemporary addiction to predictability. The whole ‘Surveillance Capitalist System’, of which Italy can be considered a fully paid up member is precisely built on this. Economic activities rely on the forecasting of natural phenomenon and human behaviours. The delusion lies in believing the two are not linked. The more random Nature seems be to, the less rational the human reaction to it is.

Bologna,on July 2020.

The Mechanic

Along the trail a mechanic repaired my faulty tyre. While doing so, he was more than happy to give a brief account of his experience of the lockdown.

For the months of March, April and parts of May his repair shop was forced to close altogether. State support was supposed to be €600 per month, but only two months of payments arrived, and after a considerable delay. State-backed loans for small businesses were difficult to obtain due to a misunderstanding between banks and the government about eligibility criteria and missing procedures. It is July, and the monthly electricity bill for the shop remains at €300 per month.

It would be interesting to find out the number of businesses that have already folded across Italy, especially with tourism at a small fraction of its usual level, with international tourists in particular staying at home.

Souvenir shop in the small town of Scicli, southern Sicily, on July 2020.

According to another source, it is increasingly common to close down businesses at least on paper, but for them to continue trading to make ends meet. The choice between punishment for tax evasion and actual survival has been effectively settled for many, across numerous sectors.

Café in Arona, northern Italy, on July 2020.

The distance between Rome’s national politics and what is happening on the ground is greater than ever. The paradox here lies in the fact that that social/political gap has increased at a time where the central state has usurped powers from local authorities to implement the nationwide lockdown.

Morning in Orvieto, center of Italy, on July 2020.

We can now certainly expect cash-rich mafioisi to expand into the legitimate economy by bailing out ailing businesses. Serious discounts are available, and they will also earn loyalty from many communities that feel abandoned by the State. This issue requires serious investigation, as the Italian State cannot afford to be undermined any further.

Grand Hotel et des Iles Borromees closed for business in Stresa, Northern Italy, on July 2020.

The collapsed tourism sector is the de-facto lifeblood of the economy in many if not most rural areas across Italy, where not much else goes on during the off season. The rediscovery of Italian locations by Italian holiday makers is insufficient for the current system to survive. We seem to be witnessing the end of mass tourism as we know it, at least for the foreseeable future, but I haven’t heard much discussion about the economic alternatives for these areas.

While crossing the Strait of Messina with a view of a Caronte & Tourist ferry, the main private navigation company operating in the Strait, Southern Italy, on July 2020.

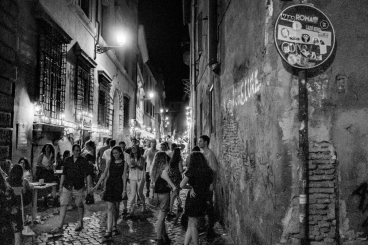

- Saturday Night in Trastevere, Rome, on July 2020.

- Friday night in Naples, on July 2020.

The crowds of people that come out at night in Naples, Rome and that are flooding into popular seaside resorts are an expression of a desire for the restrictions to come an end. I sense the calculus of risk versus safety has shifted decisively for many towards a willingness to take more risks. Even the economic decision for many families to spend a few days on vacation despite their real financial uncertainties is a sign that there is real hope of an imminent recovery.

- Sunday Morning in Pizzo Calabro, Southern Italy, on July 2020.

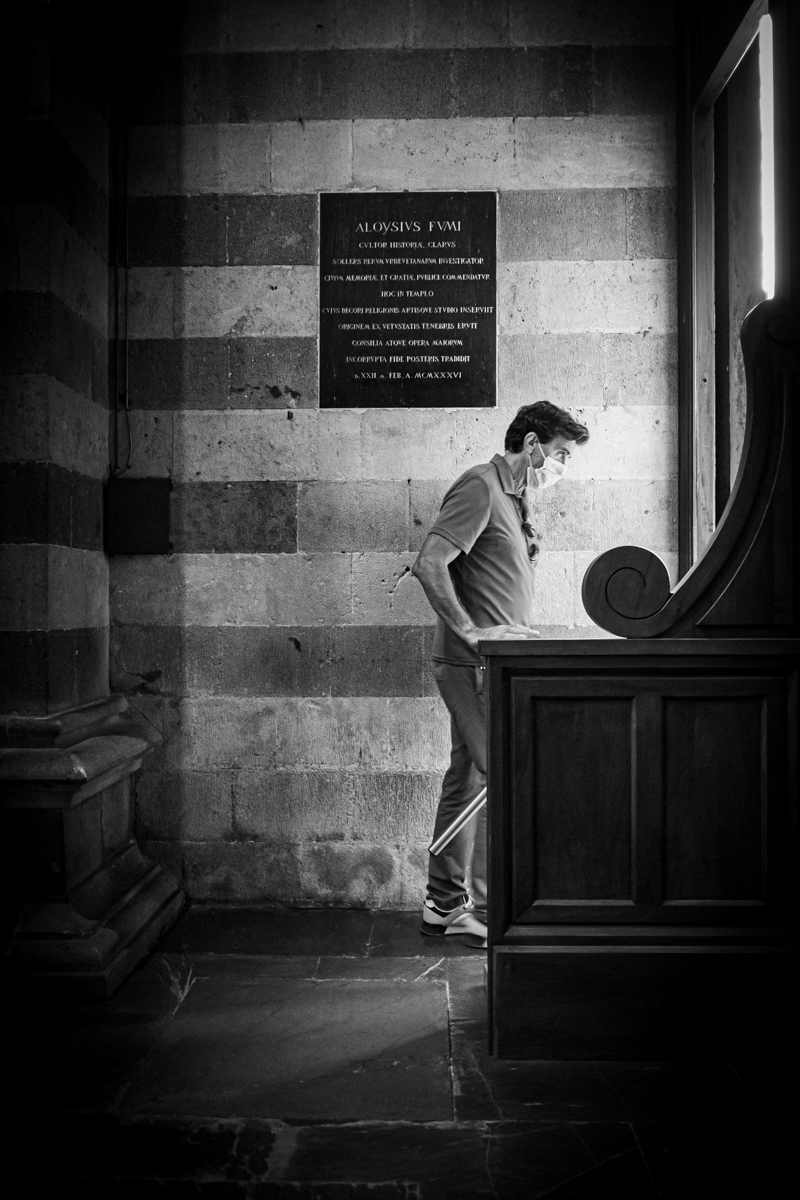

- Visitor in the Duomo di Orvieto, on July 2020.

Saturday Night in Pizzo Calabro, on July 2020.

But the truth is that mixed government messaging that shift between doomsday scenarios saying ‘Be Careful or we will go into lockdown again,’ alternating with ‘Everything will be fine,’ is creating an increasingly divisive society. Already alt-right political parties like La Liga led by Matteo Salvini or Brothers of Italy led by Giorgia Meloni are taking advantage of the divisions. The opposition are frantically attempting to come up with alternative solutions amid the usual propaganda touchstones of immigration and unemployment.

Salvini’s traces in Bologna, on July 2020.

What is not being said is that the current government is dealing with this particular situation with the bureaucratic, legal and health infrastructures that were undermined as result of decades of mismanagement and corruption, which members of that same political class in power are responsible for and in some cases complicit, having occupied key decision-making positions in previous administrations, both locally and in Rome, over the previous decades.

On the banks of the River Tevere overlooking the Aventino’s hill, Rome, on July 2020.

The erosion of the middle class and ever-widening wealth inequality was not caused by this pandemic. The massive defunding of the public health system, followed by privatisations was a process that was more pronounced in Lombardy and Piedmont. It so happens that these two regions were disproportionately hit by Covid-19. This is the bitter fruit of economic policies that emerged in the early days of Berlusconi’s twenty year dominance, and which were accelerated by the dysfunctional political class that emerged in this culture.

Bologna, on the July 2020.

Maybe, that is the reason why no significant discussions are taking place around possible reforms of the public health care system so the threat of another lockdown hangs overhead. Again, especially in Lombardy and Piedmont.

Tuesday’s market in Arona, northern Italy on July 2020.

Sadly, another lockdown could be the only antidote to the possible overwhelming of ICUs in a system that stopped hiring staff after retirements over the past ten years, and therefore lack not only physical infrastructures but especially well trained personnel to confront the possibility of a spike in infections.

Thankfully it is still summer.

- Aventino’s hill, Rome, on July 2020.

- While crossing the Strait of Messina, Southern Italy, on July 2020.

- Duomo di Orvieto, on July 2020.

- Bologna, On july 2020.

- Street Market of Porta Portese, Rome, on July 2020.

- Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome, on July 2020.