At the age of sixteen, in 2001, I took a job in a small factory which built appliances in Cardano al Campo, near Milan’s Malpensa airport. I worked there for four years.

As with the majority of the manufacturing industries in the area, including the spring-making factory I had worked in the previous year, it was a family-run, small enterprise, with just a handful of clients. Much of the machinery dated from the first half of the twentieth century. Fortunately, as it turned out, they had invested in modern machinery that would allow them to diversify their offerings, and therefore survive the global economic crash, from 2008.

I vividly recall the three newspapers that were delivered to the factory each morning: the Sole 24 Ore, the Italian equivalent of the Financial Times; La Prealpina, a local newspaper; and La Padania, the mouthpiece of the then rising Northern League (Lega Nord), which was allied at that time with Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia.

I also remember my colleagues being outraged at the protestors defending Article 18, which governs labour rights, despite this being to their benefit. I heard comments such as ‘they are mainly students with nothing better to do than going about shouting in the streets and smashing shop windows.’

Back then Northern Italy was still one of the most prosperous regions in the world, and probably still is. From 1979 to 1998, Italian industrial production actually outpaced Germany’s by more than ten per cent, and most of that was in the North. But when the crisis struck businesses similar to the one I had worked in began to cascade like dominoes.

In that factory’s industrial district more than half of the businesses folded within five years. Today in their place are parking lots for Malpensa airport.

II – Separatism

Italy is a country with strong regional identities, although separatism has been rare throughout its history, apart from sporadic outbursts in Sardinia, Sicily and small Alpine enclaves of German speakers.

When the Northern League emerged in the early 1990s it captured a lot of support in my region. The then leader Umberto Bossi was born in nearby Cassano Magnago.

As the first cracks of an unsustainable economic model were becoming apparent – well before the earthquake hit – mistrust and cynicism towards the political establishment had become widespread. This was especially apparent among the working class in the kind of businesses that I worked for, which formed the backbone of the region’s, and arguably the nation’s prosperity.

In the beginning the Northern League called for a federal model of government, inspired by nearby Switzerland, but the leadership soon became outspoken in their separatist aspirations. This was, however, quite different to nationalist movements elsewhere, such as in Sardinia, as the Northern League ceased to be a genuine threat to the territorial integrity of the country once they entered the labyrinth of national politics.

Blaming Italian society’s ills on an enemy within was their main tactic for gaining support from the beginning: the corrupt political class from Rome, Roma Ladrona, the lazy Southerner and the parasitic Roma community were convenient scapegoats, at a time when political discourse had been coarsened under Berlusconi’s dominance.

The Italian economy began to fragment in the wake of joining the euro, which did not allow for the periodic currency devaluations that had kept the country competitive. The government failed to control the price of consumer goods after the changeover, while salaries remained static. This eroded significantly the purchasing power of households.

As the global banking system imploded, and businesses migrated to distant countries with lower labour costs, fortunes were lost, savings dried up and many were left unemployed. This coincided with a rapid rise in immigration; first from Eastern European countries such as Albania, then later from Africa and Asia.

Almost overnight Italy became a multicultural society, and government services, especially in housing and education, were not prepared for the influx.

The migrants who settled in Italy became symbolic of the global forces that had proved so ruinous to many. They became the new target for the Northern League, which under Matteo Salvini conveniently buried its difference with the South of Italy, re-branding itself as simply the League (La Lega), and finding new scapegoats.

III – The New Government

As I worked in the factory I managed to complete my high school education by night, which gave me the opportunity to travel and gain a greater perspective on the world. But I recognise from my region the kind of talk about foreigners that I hear now from Salvini, and others.

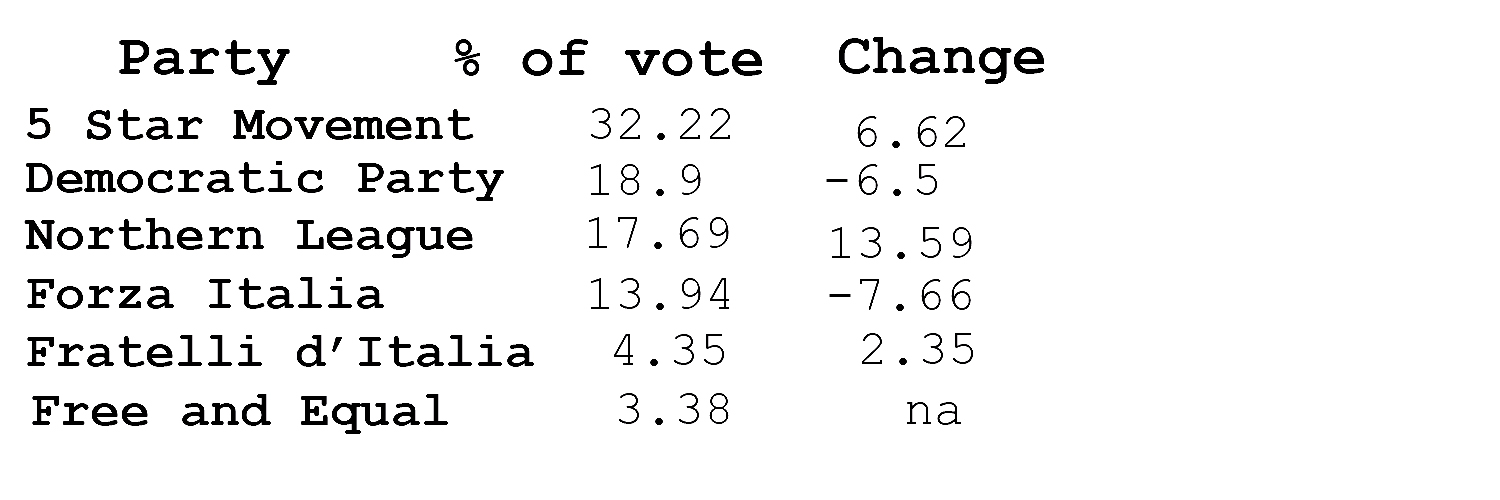

How do we explain the rise of Salvini? In the last election his party emerged as the third largest in the country and the main party of the Centre-Right alliance, which included Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and other Centre and Right wing parties.

After discussions which took months, an agreement was reached to form a government between the largest party, the Five Star Movement (M5S), which had insufficient representatives to form one alone, and the League. Crucially, Salvini was allowed to become Minister of the Interior, where he is in a position to implement xenophobic policies.

Salvini seems to understand that power is increasingly located in the social media space and below-the-line commentaries on newspaper articles and videos. One tolerant commentator might find himself against ten online reactionaries, who in their normal lives may have a quite peaceful disposition. This kind of short-attention-span politics is an ideal breeding ground for racist stereotypes and armchair experts.

When Salvini says we need to repatriate five hundred thousand illegal immigrants he receives a wave of online endorsement, despite this being a remote possibility without outrageous human rights violations being perpetrated.

Likewise, he says that we will expel all illegal ‘Roma’, but ‘unfortunately we will have to keep the Italian ones’. The key word here is “unfortunately.”

Of course it might just all be hot air. But he has tapped into an angry mood.

III – Migrations

I have been living beyond the borders of my native Italy for fourteen years now, but I am still transfixed by our dysfunctional politics as much as the next Italian, and have access to the world’s media. I have witnessed how state institutions fail and even persecute people, and could tell stories that only Italians would believe.

Like many among my generation, born in the 1980s, I had begun to despair that politics would continue to be dominated by corrupt elites – complicit or just plain lazy members of the public administration – and mafias with tentacles extending throughout every aspect of the Italian economic system.

At the same time, Silvio Berlusconi’s media empire seemed to have made pulp out of our collective brains. His Forza Italia party took over from the Christian Democrats and the Craxian left-wing faction as the dominant force after the Mani Pulite (clean hands) scandal in the 1990s. But real power lay with global elites and organised crime.

Not even the vestiges of our great civilisation and the Rule of Law could actually bring down Berlusconi. It was left to the European Community to deliver the coup de grâce. In return Italy was sentenced by its European partners to perma-austerity. Guess what: Berlusconi is still alive and kicking.

Italy has been the first port of call for the majority of Africans seeking to make Europe their home, and they have been prevented from moving further afield due to the unfair Dublin Regulation of 2014. Many new arrivals have been reduced to virtual slave labourers, or become entangled in the mafias of the South.

Meanwhile, in order to stanch the flow, the Italian government, along with its European partners-in-crime, entered into an agreement with the Libyan authorities, which has led to the establishment of internment camps for aspiring migrants, where NGOs report appalling abuses. Just last week, the European Community agreed to attempt to build further reception centres around Africa, and even within Europe. But reception of refugees by another state is on a voluntary basis, meaning nothing of any consequence will happen.

The Trumpian use by Salvini of the migrants aboard the rescue ship the Aquarius as political pawns was an absolute disgrace, but it is worth bearing in mind that what we are not hearing about in the news is probably worse. Every minute of uncertainly for every migrant creates further unnecessary suffering.

There are no easy solutions to the problems faced by Italy, and Europe. Migrants are entering what is already a densely populated country with an ineffective government. The absence of adequate accommodation makes migrants more visible, and an obvious target.

George Soros is a hate figure for many Italians because of his support for migrant rights. But his proposal for the equivalent of a Marshall Plan for Africa makes a lot of sense. It would also be useful for Italians to understand that the country’s declining birth rates mean the economy will soon need more workers. But short-attention-span-politics makes that argument difficult to make.

The hateful message of Salvini grows more powerful by the day.

V – The Cuckoo in the Nest

The emergence of the M5S seemed to offer the hope of revolutionary change in Italian society and politics. I followed Bebe Grillo’s blog from its inception, and it was a breath of fresh air, although I did not agree with everything he had to say.

The appeal of M5S is analogous to the League’s. It is Populist, reflecting, right or wrong, what ordinary people think. In particular it challenges the elites.

The question is whether the alliance which the M5S has entered into with the League is a pact with the Devil. But it was the only conceivable way for a government to be formed, once the Democratic Party stubbornly refused to enter negotiations to form a coalition. That party’s credibility faded when they embraced the politics of perma-austerity, and the sight of former leading figures like Elena Bosci cavorting with Berlusconi fills most left-leaning Italians with disgust.

Recent polls and local election results show clearly that the big winners of the coalition have been the League, who are now the most popular party in the country. The Guardian has even referred to Salvini as Italy’s de facto prime minister, which only serves to bolster his legitimacy.

But this is not true, and I remain hopeful that aspects of the M5S’s policies will be implemented, such as tackling the ridiculously high pensions awarded to retired officials. Grand infrastructural projects costing billions of euros, such as the Lyon to Turin high speed rail, which bring few benefits to the working class, may also be shelved. Perhaps too they can set about cleaning up the toxic poisoning of places such as Terra dei Fuochi, and just maybe challenge the extensive networks of organised crime.

However, the agreement entered into between the parties is highly aspirational, ranging from a regressive plan for a flat tax and a guarantee of a basic income for all Italians. It is difficult to see the government lasting very long, and the worry is that Salvini, with the wind in his sails, emerges as the big winner. Like the cuckoo in the nest.