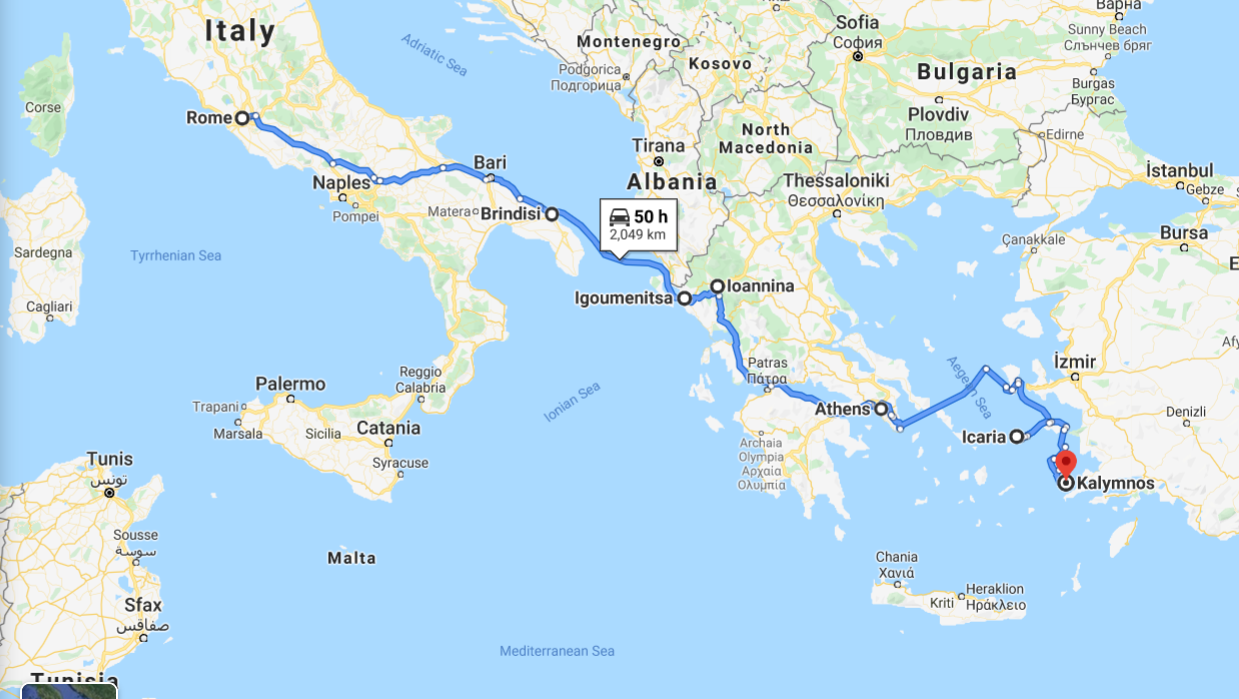

The grip of the pandemic having loosened, Frank Armstrong travelled over land and sea from Rome to Athens, and on to the Dodecanese Islands. Although Greece’s Covid-19 death toll has been among the lowest per capita in Europe, it now contends with severely diminished tourist earnings, and the worrying prospect of another war with Turkey. Contemporary Greece draws on an unparalleled history that inculcates moderation and an appreciation of nuance, but the pandemic has also triggered a more belligerent posture towards outsiders.

from google.com/maps

Hellas of the North

The Greeks are among the great sea-faring nations of the world. Indeed, from the sixth century BC Greek sailors voyaged as far as what the Greco-Egyptian geographer Ptolemy described as the islands of Alwion (Albion), Iwernia (Hibernia), and Mona (the Isle of Man).[i]

Despite the challenge of geography, Greek culture has an enduring presence in Ireland. In particular, during the early Christian period Irish monks sought seclusion in the wild places, inspired by Early Church Fathers, who came from the extensive Hellenic world of the eastern Mediterranean. James Joyce once mused of Ireland: ‘Is this country destined some day to resume its ancient position as the Hellas of the north? Is the Celtic spirit … destined in the future to enrich the consciousness of civilisation with new discoveries and institutions?’[ii]

In Book Five of Homer’s Odyssey we first meet the eponymous hero. Cursed by the sea god Poseidon for blinding his son the Cyclops Polyphemus – a feat he may have got away with had it not been for a hero complex inducing him to goad his victim – a shipwrecked Odysseus is spending an unhappy exile on the nymph Calypso’s verdant island of Ogygia. According to Plutarch this is ‘far out at sea, distant five days’ sail from Britain, going westward.’[iii] In my mind’s eye, Odysseus’s place of exile is this windswept Emerald Isle, with Joyce’s Leopold Bloom his literary incarnation.

I booked a flight to Rome in ‘green-listed’ Italy at the end of July, and made my way down to Greece. The vast majority of Italy’s death toll from Covid-19 occurred in three provinces in the north of Italy, while Greece has registered less than three hundred fatalities out of a population of over ten million.

In Greece’s case it is unclear if a pre-emptive lockdown and travel bans have had the desired effect, or whether what Karl Friston called ‘dark immunological matter’ means the population is less susceptible. Arguments in favour of the latter include especially how elders remain overwhelmingly within families as opposed to care homes, generally healthy diets and a climate conducive to outdoor gathering.

- Rome.

- Rome.

- Rome.

- Rome.

- Rome.

- Rome.

Land Ahoy!

Departing by ferry from Brindisi, we sailed down the Adriatic through the Straits of Otranto towards the Ionian Sea. After a few hours of blissful isolation, from out of the mist the rugged coastline of Albania hove into view. The sheer mountains rising out of the sea recall a steep political trajectory; from the last monarchy under the cartoonishly named King Zog (1922-39); to the post-war Communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. This terrain, now parched by August sun, was the last redoubt of Communism in Europe.

Out on deck I struck up a conversation with Christos, a street musician from Thessalonika now living in Athens, where he earns a crust playing the songs of Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, alongside more traditional tunes, in which the bouzouki figures prominently. This instrument, which entered Irish traditional music in the 1960s, is associated with the 1.6 million Greeks who fled Turkey after the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22.

- Puglia.

- Puglia.

- Puglia.

Christos had just spent two weeks in an agricultural commune in Puglia that is developing a self-sustaining way of life at a remove from both state and corporations. The experiment had imbued him with great enthusiasm, although he cautioned that non-hierarchical structures are not necessarily conducive to harmonious relations: therein lies the challenge of independence.

Ancient Greek thought from Heraclitus, who said ‘No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man,’ embraced nuance and avoided moral absolutism. Plato’s utopian ideas in The Republic are an outlier that have inspired totalitarian regimes through history. His heir Aristotle’s golden mean between extremes of excess and deficiency holds a more enduring appeal.

Albert Camus in The Rebel (1951), identified an enduring tension between a Caesarian Marxist project that permits all manner of atrocity on the journey to earthly paradise, and an approach he identifies with Ancient Greece, characterised by moderation, incrementalism and respect for tradition. He suggests:

The profound conflict of this century is, perhaps, not so much between the German ideologies of history and Christian political concepts, which in a certain way are accomplices, as between German dreams and Mediterranean traditions … in other words, between history and nature.[iv]

This tension is evident again today during the pandemic, with many governments adopting a Caesarian, command-and-control approach with the utopian objective of eliminating the virus altogether; rather than a proportionate response relying on community solidarity and individual responsibility.

- Ferry from Brindisi to Corfu.

- The mountains of Albania.

- Cruise Ship, Brindisi.

Corfu

Approaching the Greek island of Corfu a plump moon rose in the east, while to the west a red sun lingered along the horizon in a last gasp of effervescence. The cosmos seemed aligned as the first stars twinkled overhead, although a nagging worry had afflicted me throughout the journey. Anyone entering Greece must complete an online form declaring they had not tested positive for Covid-19, or been in close proximity to anyone who had.

Unfortunately I only discovered a requirement at the port to fill in the form at least one day before departure, compelling me to make it out for the following day.

Christos was in a similar pickle, but less concerned. He assured me that in Greece such a minor discrepancy was unlikely to be problematic, and advised that when I disembarked to wait at the back of the queue. This stratagem was designed to make departure from protocol easier for the border guard, with no other passengers around to witness any flexibility.

Following Christos’s instructions (he was getting off at the next port on the mainland), I finally presented my passport and an email confirming I had completed the form for the following day, which was a few short hours away. A barrel-chested guard with a black face mask obscuring all but a pair of glowering eyes barred my path. For all their history of philosophy and the arts, one should recall that the Greeks are a people forged in the crucible of warfare.

His response was decisive: “you don’t have the form. Get back on the ship.” I pleaded that it would be valid in a few hours, but I was met with no sympathy, and had no alternative but to return to the ship. At least, unlike hundreds of refugees now landing in Greece who are pushed back to sea in breach of the principle of non-refoulement, I would have another opportunity to enter Greece through the port of Igoumenitsa on the mainland.

I returned on deck and met Christos who was now worried that he too would be denied entry. An eight-hour return journey back to Brindisi would be a bitter pill for either of us to swallow. He began furiously calling various people, engaging in animated conversations that yielded little certainty as to what would ensue. He assessed our chances 50/50 as the ship entered the port; I was more hopeful given I now had a Greek accomplice.

The Port of Brindisi.

In a period where every case of Covid-19 is a blow to Greece’s ailing tourist economy that relies on keeping its case numbers low, even a Greek returning home has cause for concern if the box-ticking exercise has not been completed on time. Our predicament hardly merits comparison with a refugee on an improvised life raft being pushed back out to sea, but at least one can empathize.

The ferry shuddered into its berth in a port veiled in darkness. Descending the ramp we braced ourselves for another unwelcoming committee, and the negotiations that would ensue. Unlike in Corfu, however, there were no border guards on hand to meet us – the only foot passengers. Alone in the terminal at some remove from the passport control, we considered waiting until midnight when our forms would be valid, before concluding that loitering for another hour-and-a-half among the trucks might land us in worse trouble. Better to brazen it out we agreed.

Leaving ourselves in the hands of fate, we set off for the passport control. Christos went first, offering his passport. The guard lazily surveyed it, barely raising his head to match the photo with the face beneath the mask, before waiving him through with no mention of the form. Thankfully he repeated the same drill with mine. A few metres on I let out a little whoop. “Quiet now,” said Christos but I felt sure he was smiling under the mask.

Athens from the Hill of the Muses.

Towards Athens

Such are the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune that avoiding Corfu seems to have been a blessing in disguise, as the island of Corfu was assailed by severe storms and flooding a few days late.

Parting company with Christos, who was returning straight to the capital to resume his troubadour career – in the straitened circumstances of the pandemic – I chose a route through the mountainous north to Athens. I arrived the following day in the city of Ioannina situated at an altitude of five hundred metres along the shores of Lake Pamvotida. The difficulty of negotiating this region as a solo travel without a car soon became apparent however. Organised tours to historic sites are prohibitively expensive and buses rare. I resolved to head straight to Athens the following day.

Arriving by bus in the sprawling metropolis of over three-and-a-half million one is instantly struck by the volume of traffic chug-a-chugging over misplaced manholes along wide highways; but at least the pollution seemed to have dissipated since my previous visit as a schoolboy over two decades ago.

It was, nonetheless, cloyingly hot, a thermal layer that lingers all night over the city throughout the month of August. The advantage of this climate, however, is that outdoor congregation outside tavernas and bars is possible throughout much of the year. This may be another reason why the pandemic has had a limited impact on Greece to date, as social distancing is not scrupulously observed and masks were only made compulsory for indoor public spaces at the end of July.

My first stop was the Hill of the Muses facing the Acropolis. A muse is a source of inspiration, and it is a sign of Greek humility to attribute any genius to an external agency. I gave a prayer to Clio, the muse of history, and in a few accounts the muse of lyre playing.

When I later texted a friend to say I was surveying the Parthenon that sits atop the Acropolis he sent me a passage from St Paul’s Acts of the Apostles, which begins: ‘Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry.’

Paul discusses the resurrection with Epicurean and Stoic philosophers, and condemns Athenians for their superstitions.

32 And when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked: and others said, We will hear thee again of this matter.

33 So Paul departed from among them.

34 Howbeit certain men clave unto him, and believed: among the which was Dionysius the Areopagite, and a woman named Damaris, and others with them.[v]

The Acropolis from the Hill of the Muses.

Adherence to Orthodox Christianity remains a powerful source of identity and community in Greece. Moreover, the Christian philosophical tradition relies heavily on Plato. This has often brought moral absolutism and a lack of tolerance. Indeed, Plato stands accused of bequeathing to Christianity: ‘the best form of political control imaginable: hell’ He also excluded those agents of creative disorder from his Republic – the poets!

I discovered a tension in Greece between a more militant approach to religion, and one that embraces a transcendence reconciled to science and reason.

Although Christianity displaced most Greek pagan beliefs – that lively universe of immoral gods who steal into one another’s rooms for illicit congress – a playful irreverence is still evident in Greece today, albeit tempered by the abnormal social rituals of the pandemic.

Island Hopping

After melting in Athens for a few days I took a ferry to the island of Icaria; named after Icarus the son of Daedulus (after whom Joyce named the autobiographical Stephen Daedulus), who created wings from wax and feathers to escape the island of Crete. Daedulus warns Icarus against either complacency or hubris, advising him neither to fly too low nor too high – a golden mean – thereby avoiding the sea’s dampness that would clog his wings, and the sun’s melting heat. Alas, Icarus flew too close to the sun and crashed to his death.

Icaria.

Present-day Icaria was designated among the Blue Zones of the world where people live far longer than average, according to Dan Buettner. I am prepared to believe that the clear blue Aegean Sea is indeed a source of eternal youth; such as that sought by the sea nymph Thetis for her son Achilles, the leading Greek warrior in Homer’s other epic the Iliad. Alas, she failed to submerge him fully, and years later a well-placed arrow to the heel beneath the gates of Troy laid low that most warlike of Greek heroes.

A timeless conflict between Trojan and Greeks (or Argives as they referred to in the Iliad) appears to be still raging three millennia later in the long-standing enmity between Greece and Turkey. In July Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan’s provocative decision to convert the Hagia Sophia museum in Istanbul into a mosque generated heated passions in Greece. There is now a real possibility of warfare erupting over the small island of Kastellorizo that would give Turkey drilling rights over natural gas fields nearby.

Icaria.

In Icaria, the legacy of constant battles is evident in crumbling fortifications along the cliffs approaching the capital Agios Kirykos. This was the scene of one of the last German victories of World War II – the Dodecanese Campaign of late 1943.

The island is known throughout Greece as the ‘red rock’ on account of its long-standing Communist sympathies, which appear to coexist comfortably with religious devotion. Indeed, the Blue Zone study attributes favourable health outcomes to a community congregating in worship.

Curiously, despite the pandemic, and the susceptibility of the older population who disproportionately attend church, many consider it disrespectful to wear a mask during services. More worryingly, the shared-spoon ritual when taking the Eucharist remains sacrosanct. This is now leading to friction within families.

Alas, due to pandemic restrictions the festivals that form an integral part of traditional life did not occur this year. In an era of expanding government interference in all things Bacchanalian, it is worth considering the health benefits of festivity.

I was able to avail of accommodation at historically low prices in the month of August. This is bound to create shortfalls in an economy highly dependent on external income: “We will have no money in the winter,” my landlady cheerfully stated, “but we will have the food from our gardens and hopefully the tourists will come back next year.”

Icaria seems likely to welcome more tourists next year, but any warfare with Turkey could put this and many other islands out of reach for the foreseeable future, compelling the native population to fall back on their resources.

The Mask Slips

My last stop was the island of Kalymnos, one of the Dodecanese chain a few hours south of Icaria, closer still to the Turkish mainland. From Agios Kyrikos I caught a high-speed ferry that bumped along at a furious rate, passing a succession of sunburnt islands rising obstinately from the sea.

Kalymnos.

Buffeted by sea winds, I marveled at the scene as I stood out on deck, when a pair of coast guards suddenly loomed in front me. I then realised my mask had slipped onto my chin, and braced myself for a hefty fine. Thankfully they restricted themselves to a ticking off, to which I responded with utmost obsequiousness.

Further along the deck two Germans were not so lucky. Despite being about ten metres from anyone else – and brothers seemingly too – they were each issued with €200 fines for failing to have their masks in place.

Perhaps those two fine Teutonic specimens, one clad in garish Ralph Lauren attire, the other more understated but still standing out from the crowd, were a sore reminder of ancient and modern foes: the occupying Nazis of the 1940s, and that more recent imposition of crippling austerity after the economic crash; a policy still identified with the former German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble.

Kalymnos.

The capriciousness of the measures seemed obvious when the guard completely ignored a Greek lady nonchalantly smoking a cigarette as they re-entered the cabin. Piracy at sea has long antecedents in this region, and the Covid-19-era appears to be opening up new opportunities.

Kalymnos is an altogether busier and more prosperous island than Icaria, renowned for its sponge diving. The capital Pothia is a large port that would ordinarily enjoy throngs of visitors in the middle of August. Now there were mostly mournful restaurateurs sullenly sitting outside their kitchens, while innumerable cats lingered inquisitively in doorways.

I chose to stay at the furthest remove from Pothia at the isolated resort of Emporios, with a permanent residence of just twenty souls, and accessible by a bus that only operates three times a week.

On the return journey a few days later I became keenly aware of the precipitous drop to the sea below from a road snaking along the cliff face. One false turn and we would crash to our doom. I grasped the hand rail tightly, wondering how that last moment of life would feel before an overwhelming concussive impact that would give way to an eternity of silence. Thus reconciled to my own mortality, and with an enhanced awareness of how all life hangs on a thread, I was ready to end my own short exile.

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are,

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

From Ulysses by Alfred Lord Tennyson

[i] Philip Freeman, Ireland and the classical world. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2001. p. 65.

[ii] James Joyce, Occasional Critical and Political Writings, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000, p.124

[iii] Plutarch, Concerning the Face Which Appears in the Orb of the Moon, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Moralia/The_Face_in_the_Moon*/D.html

[iv] Albert Camus, The Rebel (translated by Anthony Bower), Penguin, London, 2000, p.240

[v] Acts 17:16