Having grown up around favelas in the East Side of São Paulo I was expecting a similar scene of poverty mixed with a strong sense of community. Instead Moria has a post-war feeling, as it is for many people living there, who showed me evidence on their phones of the destruction they were escaping. It’s a tough and unfriendly place, until you meet the families.

The first smell that hits you is the smoke from wood, plastic and anything else that burns, as they cook on open fires. A blind person would think the whole place was on fire. The second smell is a strong male odour. It’s there because there are hardly any facilities for people to wash.

It’s completely dirty everywhere. The bathrooms are covered in shit. It’s even on the ground where people do business and cook food.

But life goes on. There are market stalls selling soft drinks, fruit and vegetables and clothing. I met two barbers working within their communities.

“The first smell that hits you first is the smoke from wood, plastic and anything else that burns, as they cook on open fires.” Moria Camp, Lesbos, December 2019. Fellipe Lopes.

The air pollution and dreadful hygiene cause a lot of sickness. The men also smoke a lot. Everyone is coughing all the time. I developed a chest infection myself afterwards. The Irish doctor said it came from bacteria prevalent in camps such as this.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) do have a medical facility, but the clinic is overwhelmed. They can’t accommodate everybody. Whether you get medical attention also depends on which camp you live in. If you are lucky you might get to attend a hospital in Mytilene, the capital and main town of the island of Lesbos.

At one point a lady from Syria showed me a document indicating she suffers from cancer, but she wasn’t receiving the medication she requires.

Many of the kids have skin problems. But the worst part is the mental torture of living in the camp that brings out the worst human characteristics.

‘I heard the noise of stabbing’

People are regularly stabbed to death. Every day there is another story, and a lot of these cases are going unreported.

At one point a guy passed five metres away from me with a machete, a massive knife, and I heard the noise of stabbing. As a photo-journalist my instinct was to go and take a shot, but as soon as I moved a friend, Mohammed, held me back, saying what must have been “don’t go” in Arabic. I understood from the strength he exerted that I shouldn’t move.

An African man had been killed. The perpetrator disappeared. This sort of thing happens every single day in a camp built for a maximum of 4,000 people, now housing more than 20,000 and growing. A friend said that over the last two weeks another two hundred tents had been erected. I looked down and saw a wave of them across the hillside.

Yet I didn’t feel unsafe. As the days went by I became more confident. I knew the friends I had been introduced to would protect me. That’s how it works in Moria.

Moria Camp, Lesbos, December 2019. Fellipe Lopes

When you enter the camp you notice the separation between nationalities. In one part there are Africans, mainly from Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia and Congo, in another you find the dominant Afghan groups, with black and white scarfs speaking different languages. There is a small part of the camp where the Syrians live.

I grew close to the Syrian community, speaking a mixture of broken Arabic and broken English, and also using phones to translate. Most of them say the system is not working for them; that if you are a Syrian in Moria you have no chance of being relocated elsewhere in the European Union. You will be denied documents.

Many Syrians believe they are stuck there forever. I met members of one family who have been waiting for a year-and-a-half now.

In general, cases are not being resolved. There are people waiting for official refugee status, or waiting other documentation. Each case is different. But some people are being scheduled for appointments in 2021, just to start the process. Until then they are not permitted to leave the island. They have to sit and wait in the apocalypse that is Moria.

The Prison’

There are three areas in the camp. First there is the so-called ‘Friendly Campus’ run by Movement on the Ground, which has most of the better accommodation, which is not saying a lot. Throughout the camp you find structures built from any wood and plastic they find, and tents of different sizes; some are big enough to sleep twenty people, others are the kind of two-man tents you would expect to see at a music festival.

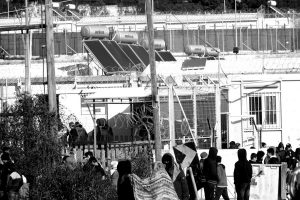

Then there is ‘the Prison’, which is the original camp. There you find the so-called ‘boxes’, which are temporary structures, some of which even have AC devices that take the chill off the freezing January temperatures. Journalists are not allowed to enter this part. A bus sits at the entrance with eight policemen bearing big guns. But where there is a will there is a way.

The Prison, Moria camp, Lesbos. Fellipe Lopes

I entered with a small camera inside my jacket pocket. People were helping me to get in and out. They knew when and where there would be no cops around and I could walk in and out.

Another part is called ‘the Jungle’, which is really a forest where people are living. I met one guy who had carved a hole in a tree and now sleeps inside the bark with a plastic sheet for shelter. A man forced to live inside a tree in the European Union in 2020.

“I met one guy who had carved a hole in a tree and now sleeps inside the bark with a plastic sheet for shelter.” Moria camp, Lesbos, December 2019. Fellipe Lopes

There is a part of the camp that has electricity, and where people can charge their phones. Most parts, however, have no access whatsoever.

They cook for themselves, improvising with things like old paint tins over open fires. The camp is next to an olive grove so there is some wood available and they burn whatever else they can find.

There are two options for food. The first is to take it directly from the camp dispensary. There you queue and receive a free meal. On Sundays you get chicken and rice; for the rest of the week it’s beans and vegetables.

But the food is awful. I couldn’t imagine eating it. So what most families do is recook it, using containers to carry it to their fires, mixing it with the spices they carry. It seems to become a bit more digestible.

Another option is available to families who receive allowances of approximately €90 per month. They can catch a bus, or take a one-hour-and-a-half journey by foot, to the island’s capital Mytilene and purchase the cheapest food they find in the supermarket, usually rice, beans or noodles.

How much any family receives seems to be a lottery. There is no apparent formula. Some families get nothing. The lucky ones are given a UNHCR MasterCard with credit on it rather than hard cash.

For water there are taps to refill plastic bottles. I drank it a few times and thankfully it didn’t make me ill. Locals don’t seem to drink the tap water.

Moria camp, Lesbos, December 2019. Fellipe Lopes

The frequency of rape

Until I came to Moria, I had never been to a place where there was no sense of hope. In the favelas people have a seriously tough life, but most of them believe that things will get better. In Moria, however, ninety percent of people I spoke to believe they will be staying there forever. They don’t see a future, believing either they will be killed, or live out their days there. Just a few families I spoke to saw a light at the end of the tunnel.

One thing I heard that made me feel really emotional was that I was bringing hope: “you are a guy from Brazil living in another country. You are an immigrant too who came here to tell our stories”.

In the camps there are loads of suicides, including kids under the age of ten.

One thing I should say is that rape is getting more frequent inside the camp. Women are of course victims, but I have heard that a number of young boys between the ages of seven and twelve have been targeted too.

One man came to me and told me his heart was breaking. He took my phone, translating from Arabic into English that his young son had been raped in the bathrooms. He said he was afraid to inform the authorities because he feared retaliation. As a result he, and others, keep their kids inside the tents.

Some of the families do manage to send their kids to school. But I didn’t hear of any teenagers attending high school. They go to cultural centres, the Hope Project and One Happy Family, where they spend an hour painting or playing football, and can take English lessons. But there is no regular schooling for that age group.

Empowerment and Love

European NGO workers say they want to empower people living in the camp. But how do you empower someone living in these conditions? The NGOS are doing what they can, but people are unfamiliar with the European concept of empowerment.

Yet around the rest of the island life goes on as normal. You would hardly even know Moria existed, with farmers working the fields, on an island that is a place of great natural beauty, and still popular with tourists.

There is some local sympathy for the refugees, but it has to be said most people are inclined to ignore them. Taxi drivers were asking why I was going there, or warned me against visiting.

On one occasion I was in a supermarket where a cashier refused to serve a Congolese man. She just told him to get out. She said he couldn’t make his purchase. She wouldn’t accept his card, so I intervened to pay for his drink and snack.

Another time a Syrian family came along with us to a restaurant. The waiter would not direct a word at them, and looked for the permission of myself and my colleague Caoimhe Butterly for what they could order.

I was lucky enough to be staying in guesthouse accommodation in Mytilene. Every night when I called a taxi to get away from the foul-smelling camp I felt a wave of guilt. Knowing how those people were living made me uncomfortable in my clean bed.

On New Year’s Eve we hung out with friends from Syria, Ghana and Ethiopia in the town. We went to a bar, where people were drinking and taking drugs.

Towards the end of the evening Haya from Syria began crying. She said: “I wished so much to be outside the camp, and now I see those people having fun and I just miss my family. I just want to be in the box. Because that is all I have left in my life. I don’t have money, I don’t have a job, I don’t have expectations. The only thing I have left is my family, and I’m here.”

That broke my heart, as I had a similar feeling after a phone call with my mother in Brazil. At the end of the day you have your family.

What holds those people together? It is love. There is no social programme. There is nothing from the U.N. and there is nothing much from the NGOs either. If you get close to them, to the families, what you find is loads of love between them, and kindness to strangers. That generosity of spirit holds us together.

Twitter:@fellipelopes7