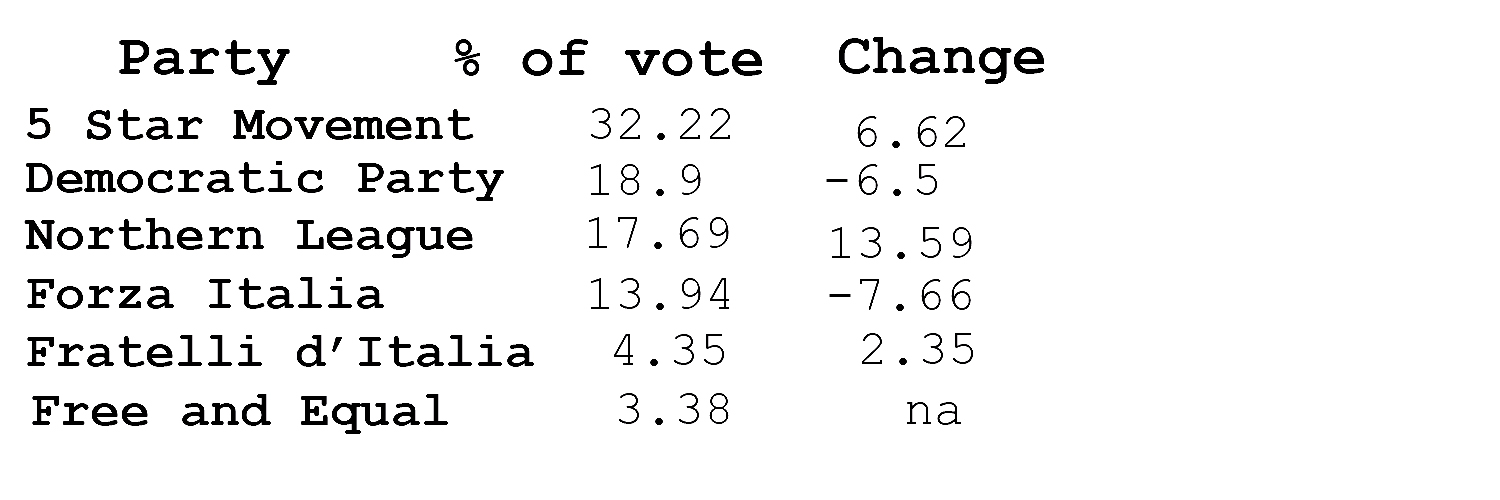

Posterity will determine if the Italian election results of March 4th 2018 marked an earthquake that will endure in the landscape. Or will a result, apparently seismic, turn out to be like the volcano that smoulders, without ever fully clearing its throat? No one is quite sure the precise dish the electorate will be served after the election.

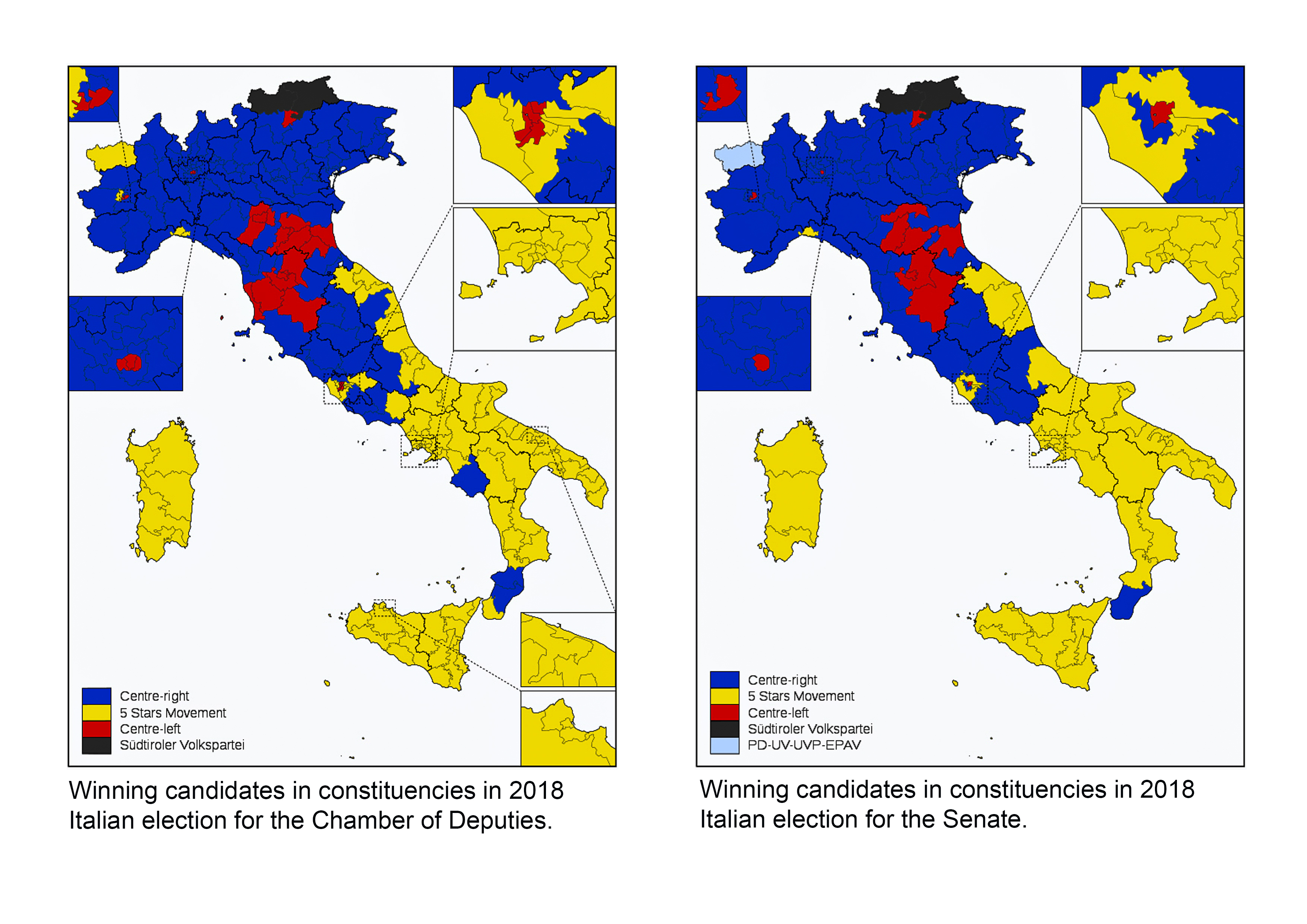

The success of the Eurosceptic and unashamedly anti-immigrant Northern League under Matteo Salvini (now seemingly reconciled to preserving the territorial integrity of the Italian state), and to a greater extent, the relatively unknown quantity of the Five Star Movement (M5S) led by Luigi di Maio, combined with the decline of Silvio Berlusconi’s centre-right Forza Italia and the centrist Democratic Party under Matteo Renzi, reflects a Europe-wide populist surge; the decline of traditional parties, and emphasises the waning legacies of iconic figures of the first decade of the twentieth century, such as Tony Blair, Nicolas Sarkozy, Bertie Ahern and Berlusconi himself.

But the widely-bandied term ‘populist’ tells us very little, and is often used simply to dismiss the popular appeal of a party by those opposed to its objectives. In a recent European context it has become shorthand for increasing xenophobia, and outright racism, triggered especially by the refugee crisis of 2015, and associated with the ‘strongman’ leadership of Putin’s Russia.

M5S has been criticised both within Italy, and in the international media, for reflecting prejudices commonly expressed in Italian society. On the other hand, there is often a failure to recognise the determination of the Movement to clean up Italian politics, particularly in their southern electoral strongholds.

Roger Cohen of the New York Times crudely dismisses M5S, lumping them with the Northern League, as one of the ‘out-with-the-bums parties’, and linked to Europe-wide ‘angry illiberal movements’. An apparently “illiberal” approach to immigration may largely be explained, however, by the responsiveness of M5S policies to the concerns of supporter, rather than any racist demagoguery emanating from its leadership.

Such criticism also ignores how Italy is the first port of call for the majority of refugees who take the Mediterranean route into Europe, and how other states are not rising to the challenge of accommodating more new arrivals.

M5S offers a new political formula that could easily have continent-wide ramifications. They promote technocratic expertise, with an emphasis on sustainability at a local level. The ‘five stars’, refers to the party’s five core values: public water access, sustainable transportation, sustainable development, a right to Internet access, and environmentalism. These founding principals clearly distinguishes them from the Northern League, and authoritarian regimes in Poland, Hungary or Russia.

One of their most important rules is that any political career is a temporary service: no one who has already been elected twice at any level (local or national) can be a candidate again. Elected representatives put a proportion of their salaries back into a micro credit fund for small businesses, and reject campaign contributions. In short, M5S is attempting to inoculate itself against prevailing corruption, and ‘strongman’ leadership.

But whether M5S can simply focus on discrete objectives and local issues, while ignoring national, regional and global institutions, is doubtful. Environmentalism can morph into short-term nimbyism. Moreover, without being corrupt or paternalistic, an elected representative may offer a course that is not instantly popular in a direct democracy scheme but may prove wise, and popular, in the long run.

There are parallels with the current political constellation in England (if not the wider United Kingdom), where the Northern League plays the character of UKIP, the Eurosceptic right the Tory party; Forza Italia assumes the part of a Europhile Tory rump; the Democratic Party is represented by ‘New’ (an increasingly obsolete description) Labour ; and the Five Star Movement (less the political nous of a veteran such as Jeremy Corbyn) reprises the role of a Euro-doubtful Momentum.

But of course Italian politics is unique in many respects. This is a long-legged country with characteristics of an ‘Asiatic’ Mediterranean, and a ‘Germanic’ North, as well as its own, often intoxicating, Latin inheritance. There is enduring, embedded, wealth alongside grinding, endemic poverty, mainly below the Mezzogiorno, but increasingly found in all major urban centres. The significance of Milan lying at a latitude closer to London than Palermo should not be discounted.

II

In many respects Italy is a fractured polity and unstable democracy, which emerged out of a long fascist dictatorship (1922-45) under Benito Mussolini, and wartime alliance with Nazi Germany. During the Cold War most governments lasted less than a year, and featured a revolving cast of roguish characters, foremost sevent-time Prime Minister, and twenty-seven-time minister Guilio Andreotti. In that time Italy’s Communist Party was the largest in Europe (with a membership exceeding two million under the astute leadership of Palmiro Togliatti), which despite not participating in governments held the feet of the ruling elite to the coals.

The Master and his Apprentice. ©INTERNATIONAL PHOTO/LAPRESSE 12-06-1984 ROMA SPETTACOLO NELLA FOTO: SILVIO BERLUSCONI E GIULIO ANDREOTTI

Corruption has long been the bane of Italian politics, particularly in the south of the country. Between them the Neapolitan Camorra, Calabrian Ndrangheta and Siclian Cosa Nostra have maintained fiefdoms the like of which are unknown in other Western European country, with tentacles reaching into the rest of Italy and beyond.

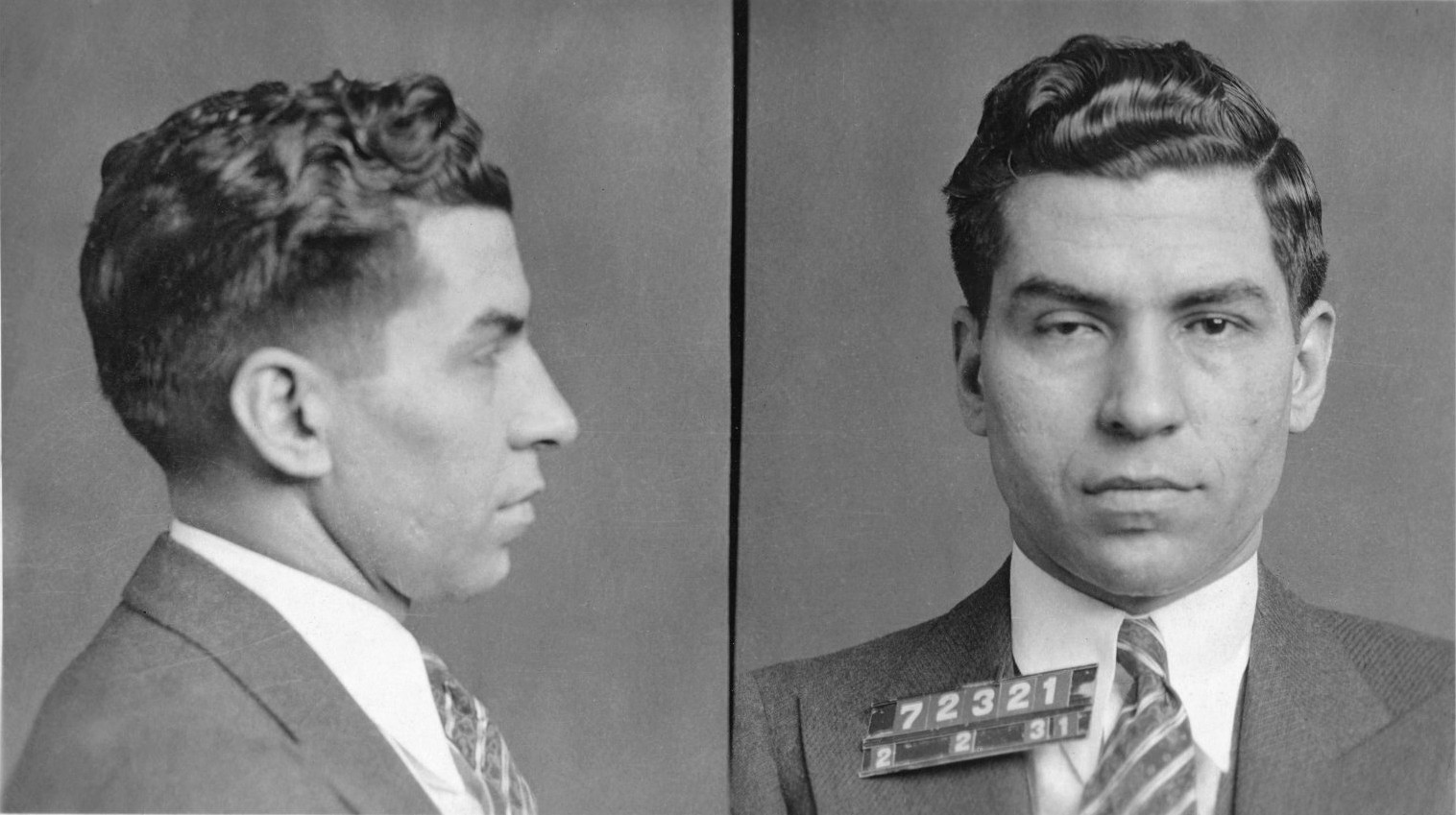

The endurance of organised crime can be traced to the Allied conquest of Italy during the Second World War. The fascists had kept local chieftains under the thumb, often by simply imprisoning them without trial. But just as de-Baathification in Iraq after the invasion in 2003 unleashed underlying, atavistic forces, similarly, across southern Italy after 1945, gangsters entered a vacuum left behind by a decapitated state.

Only after the fascist prisons were thrown open, and shadowy American Intelligence figures such as ‘Lucky’ Luciano arrived on the scene, was a humanitarian crisis averted. Reliance was placed on old networks of patronage to feed the population, as Norman Lewis’s account in Naples 1945 illuminates. Italian democracy has been counting the cost of Allied authorities ‘looking the other way’ ever since.

‘Lucky’ Luciano, unlucky Italy.

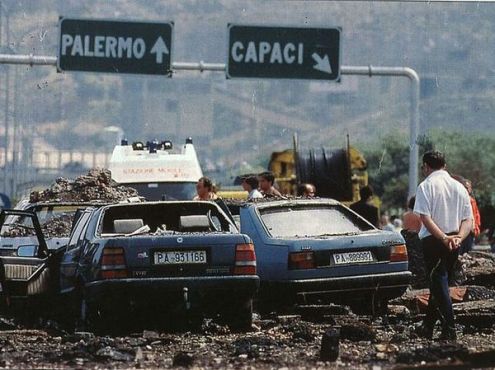

Any journalist investigating their affairs whether in Italy or elsewhere, as the recent likely contract killing of Slovak journalist Jan Kuciak and his partner Martina Kusnirova reveals, must be aware of the dangers. Investigating judges require huge security details; even then some, such as Judge Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino in 1992, are still assassinated.

The scene of the Massacre of Capaci where Giovanni Falcone, Francesca Morvillo and their police escort were killed by a Mafia bomb. 23 May 1992.

The Mani Pulite (clean hands) judicial investigation into corruption of 1992 brought the false dawn of a Second Republic. Electoral laws were amended and the Christian Democrats, which had provided the Prime Ministers to all bar three post-war governments until that point, disappeared entirely.

However, a corrupt deck was merely shuffled, and many Italians lost faith in politics altogether during the lost decade (2001-2011) of billionaire Berlusconi’s showman leadership. His clownish antics provided a front for deepening corruption, while the television media he controlled provided a drip-feed of light entertainment, football and titillation that kept the patient Italian public in a mildly delusional state. Here M5S politician Alessandro di Battista reads out a court ruling against a former longtime aide to Berlusconi and the founder of Forza Italia, Marcello Dell’Utri, who is in jail because of his links to the Cosa Nostra.

Mr Berlusconi paid the mafia association “Cosa Nostra”: let the entire world know!

BERLUSCONI HA PAGATO COSA NOSTRA, FACCIAMOLO SAPERE AL MONDO!Questo paese deve rialzare la testa. Io sono stanco di sentire il popolo italiano paragonato a Berlusconi. Ci sono milioni di cittadini che per anni hanno dovuto subire i suoi comportamenti disdicevoli e l’onta di essere accostati a lui. Dobbiamo far sapere al mondo che in Italia la musica è cambiata, che il popolo italiano non vuole più saperne di chi ha finanziato e quindi sostenuto l’associazione a delinquere che ha ucciso Falcone e Borsellino. Ecco come:Copiate questo testo e inviatelo o incollatelo sulle pagine Facebook delle principali testate straniere come Washington Post , The New York Times, TIME, Financial Times, The Guardian, The Independent:"Dear Director, dear journalists, I do not know if you read about this, but some days ago hundreds of Italian citizens gathered in Arcore, Italy, right in front of Mr Berlusconi's place. Together, they read the sentence that convicted Mr Marcello Dell'Utri, Mr Berlusconi's right-hand man, as well as founder of his party Forza Italia. Mr Dell'Utri is now in jail, convicted of mafia.This sentence reads, loud and clear, that Mr Berlusconi paid the mafia association "Cosa Nostra". By doing so, he contributed to make the mafia stronger. What Mr Berlusconi did, was to strengthen the organization which killed the anti-mafia judges Mr Falcone and Mr Borsellino back in 1992.Dear Sirs, please bear in mind that there are millions of Italians who are really outraged by all this. You must know that there are millions of Italians who struggle everyday, who raise their heads and speak up, who do not forget, who say out loud that the "mafia is a mountain of shit" and who think that jail is the only place where Mr Berlusconi belongs.I ask you to please watch the video and read these words.Have a nice day and thank you".Aiutateci tutti, dobbiamo fare arrivare il nostro messaggio il più lontano possibile. Gli italiani meritano di più di una caricatura che li ha presi in giro per 25 anni e ha pagato la mafia, uno dei mali peggiori del nostro paese. E se le testate italiane hanno paura di dirlo, allora che lo facciano quelle straniere!

Alessandro Di Battista paylaştı: 20 Şubat 2018 Salı

The period since the end of the Cold War also witnessed a steady rise in inequality, and the effects of the economic crisis, beginning in 2008, continues to be felt. In 2017 the bottom 30 percent of the population was at risk of poverty and social exclusion. That is up from 28.7 the previous year.

Berlusconi also coarsened political debate, bringing respectability to the expression of prejudice against foreigners living in Italy, thereby providing an obvious scapegoat when times grew hard.

III

In a wide-ranging account, Delizia – the Epic History of Italian Food (2007), John Dickie describes Italian food at the turn of the twentieth century as ‘local rather than national, whereas French cooks were armed with a uniform terminology – coulis, hors d’oeurvres, potage – their Italian counterparts spoke a variety of mongrel food dialects’.

Dickie continues: ‘The history of Italian food after unification is the story of the relationship between these proud local food cultures, and the dream of bringing all of Italy to one table, thereby creating a national cuisine to rival that of France’. This fragmentation reflects a prevailing loyalty towards town or region, rather than country or nation.

The history of the pizza is instructive. It shares a provenance similar to Greek pitta and Turkish pide, as part of an extended family of Mediterranean flat breads. The author of Pinocchio, Carlo Collodi (1826-90) dismissed this Neapolitan dish as ‘a patchwork of greasy filth that harmonises perfectly with the person selling it’. The Margherita pizza, named in honour of Queen Margherita’s visit to Napoli in 1889, represents the colours, red (tomato), white (mozzarella cheese) and green (basil), of the Italian flag. More importantly, its name accommodated the people of a city, renowned for poverty and disease, within the new nation’s gastronomy.

Dickie likens the Margherita’s propaganda value to Princess Diana embracing AIDS victims. But Napoli’s waste management problems continue to this day: in 2015 Europe’s biggest illegal dump –‘Italy’s Chernobyl’ – was uncovered nearby. The greasiness of Italian politics, like the layer of mozzarella on top of a pizza, has long held in check progressive forces of green and red.

Despite Italy’s relative novelty – unification only culminated in 1871 – this is an old country. The architectural layers found in almost every city are a daily reminder of past glories. Italians generally seem unmistakably Italian, no matter where they are from on the peninsula or islands. Notwithstanding regional variation, there is a quintessence to life across the land. Bureaucracy and conviviality represent the poles of annoyance and enchantment any resident or outsider negotiates.

The nation’s varied constituents were never static aboriginal communities. A central location in the Mediterranean, pointing into Africa but firmly lodged in Europe – the Alps were the ‘traitor’ of Italy according to Napoleon – has brought migrant waves since time immemorial. Anyone who is anyone has spent time here, from Hannibal to Lord Byron and Gore Vidal.

It is now the main entry point for Africans who aspire to live in Europe. Italy took some 64 percent of the 186,000 migrants who reached Europe in 2017 through the Mediterranean route. It took the majority of these migrants in 2016 too. The current surge is unprecedented but there is no end in sight as looming Climate Change threatens further mass movements of peoples. Recent new arrivals join five million foreign nationals already living in Italy. It is estimated that there are as many as 670,000 illegal immigrants living in the country.

Desperate people are being trafficked across the Mediterranean aboard flimsy vessels, while the European Community washes its hands. The Dublin Regulation (2013) ordains that any decision on refugee status falls for determination in the country where a person first lands, unless family reunification is involved. Many Italians argue other European countries are not sharing the burden, and they have a point.

With a prevailing sense of being overwhelmed by immigration at a time when the economy is still in remission, predictably, extremism is on the rise. Berlusconi broke taboos that many politicians now habitually cross.

On February 5th Luca Traini, a former candidate for the Northern League, was arrested after targeting African migrants in a two-hour drive-by shooting spree in the Marche city of Macerata. This came days after the discovery there of the body of an eighteen-year-old Italian woman, allegedly killed and dismembered by a Nigerian immigrant gang. The threat of further bloodshed is acute.

In its aftermath Silvio Berlusconi called for the expulsion of thousands of migrants, while League leader Matteo Salvini said ‘those who fill us with migrants instigate violence’.

IV

The Five Star Movement is the sulphur in the Italian political wind, whose promotion of direct participation of citizens in the management of public affairs through digital democracy could provide an example well beyond Italy. But in any situation where an electorate is ill-informed by a media dominated by vested interests this can have dangerous consequences, no matter how progressive the core ideas of any movement. However, the despondency of some commentators regarding the capacity of the Internet to inform, as opposed to trigger prejudice, may be misplaced in the long term.

M5S propose a fusion of green and red politics that should have admirers beyond Italian shores: they embrace theories of de-growth, and support ‘green’ employment. The need to stop polluting Italy’s environment is recognised, and they call for an end to expensive ‘great works’, including incinerators and high-speed rail links. They aim to raise the quality of life and bring about greater social justice.

But the thorny issue of their approach to the European Community remains, which is closely connected to resolving the immigration imbroglio. Somewhat disconcertingly, after a ballot of members a decision was made to join a political group in the European Parliament which also contains UKIP. The option, however, of joining the Greens/EFA group was also discussed, but was unavailable due to that group’s prior rejection of the idea.

For a country like Italy to leave the Community would be a hammer blow from which it might not recover, at least in its present configuration. Moreover, in a globalised world it is surely impossible for any one country, especially one so unstable as Italy, simply to go its own way, at least with a democratic government. Removed from the European mainstream, Italy could easily fall prey to authoritarian government, which is part of its political DNA.

©Daniele Idini

Leading members of M5S have at times offered inflammatory views on immigration, in particular Beppe Grillo, its animating spirit. On 23 December, 2016 he wrote on his blog that all undocumented immigrants should be expelled from the country, and that the Schengen Accord, allowing free movement of people between signatory states, should be temporarily suspended in the event of a terrorist attack.

Grillo seems to have been panicked by the terror threat. In the wake of the 2016 Berlin attack and the killing of a suspected terrorist near Milan he wrote: ‘Our country is becoming a place where terrorists come and go and we are not able to recognise and report them and they can wander all over Europe undisturbed thanks to Schengen’.

On 21 April 2017, Grillo also published a piece questioning the role of NGOs operating rescue ships off the coast of Libya. He suggested they may be aiding traffickers. Grillo’s comments raise serious questions over whether M5S will calm the growing scapegoating of immigrants in Italy. While his views may reflect what many Italians feel, it is surely incumbent on a politician to lead rather than follow, and not to exaggerate any threats.

Fortunately the M5S is a broad church, and Grillo, while still influential, is not their leader in parliament. Last year Luigi Di Maio called for ‘an immediate stop to the sea-taxi service’. He also said he would support a referendum for Italy to leave the Eurozone and would vote to leave. In January 2018, however, he reversed his previous position. What appears to be the relative abatement of the terror threat will, hopefully, go some way towards calming the fears of many Italians. But other European states must recognise that preserving the European Community will require a sharing of the refugee burden.

V

In his 1963 account The Italians, Luigi Barzini endeavours to explain why his countrymen have historically failed to coagulate into a singular nation. Firstly, he points to ‘rapid and enthusiastic acceptance of changing political fashions and of foreign conquerors which made all revolutions irresistible but superficial and all new regimes unstable.’ This might be identified in the enthusiastic post-war approval of Communism, and the earlier groundswell of support for Mussolini’s Fascism. The MS5’s embrace of digital democracy has been dismissed as a political fad in the era of the Internet.

Secondly, Barzini found ‘an art of living as if all laws were obnoxious obstacles to be overcome somehow, an art which made the best of laws ridiculously ineffective’. This reflects a permissive attitude towards organised crime, which M5S are at least seriously challenging.

Finally he averts to ‘the certainty that the most inflexible government could, in the long run, be corroded from the inside.’ This final point is important in terms of understanding the reluctance of many among M5S to work with other parties to form a government. It is also reflects the cynical response of many commentators to the efforts of the M5S leadership to form a government. Italy requires meaningful reforms and this will require deals to be done, even with the Northern League, who are surely no worse than Berlusconi’s cronies. It is unfortunate that the Democratic Party, with whom M5S should have most policies in common, have expressed a determination to remain in opposition.

It would perhaps be wise to recognise that politics is the art of the possible, and that reforming a political system as dysfunctional as Italy’s will take considerable time, but at least the priorities of M5S appear progressive in terms of social justice and sustainability. Perhaps most important are the precautions the Movement are taking against ‘strong man’ leadership, which could be a template for other political systems to follow.

Frank Armstrong is the content editor of Cassandra Voices.

Featured Image: Daniele Idini