I felt myself still reliving a past that was no longer anything more than the history of anther person. Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time.

I

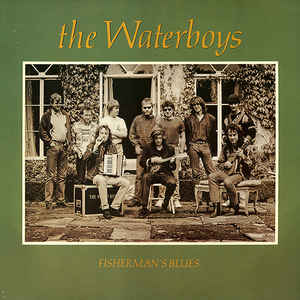

It got to a point that whenever I searched through a friend’s record collection when staying with them it stared right back at me: The Waterboys’ Fisherman’s Blues. Whether in Dublin or London, Berlin or Oslo, it was stood out like a sore thumb.

The weird thing is we never professed much grá for the album when it came out in the 1980s. We were coming of age teens when news filtered through that the older crowd were out jamming with The Waterboys in Spiddal. At the time ‘The Whole of The Moon’ bookended teenage discos across the West; a cue for a crowd to go off on one.

The Waterboys were solid purveyors of ‘big music,’ a band destined to play stadia across Europe; a band critics tipped to be the next U2.

So why the decamp to Spiddal of all places? We couldn’t get our heads around it. We were happily pushing our high-minded ideas into the world but it seemed like a step into an abyss. Some called it career suicide and we nodded in agreement. One minute the band was on Top of the Pops, the next they were playing sessions in a Spiddal pub. No sooner had Fisherman’s Blues come out, then the songs filled the airwaves. We had to engage with the music that was all around us. But we never professed to like any of the songs.

Pointing the Needle

Thirty years later I peered into the record collection of one of those former teens and Fisherman’s Blues was there looking out at me. It was the morning after a cold and wet November night spent sleeping on a couch, as my friend left for work.

I made a coffee and rummaged through his record collection. There it was: a vinyl copy of Fisherman’s Blues in its striking green jacket. I pointed the needle, lay back on the couch and listened to it straight through. It was a bewildering experience; the object of what I had rebelled against as a teen so defining of those same years.

Those days when noses were turned up at rock stars decamping to the West of Ireland to play trad had passed, and the singles ‘Fisherman’s Blues’ and ‘A Bang on the Ear’ became anthems.

Fisherman’s Blues came out when the West was a still a relatively unscathed tourist destination. It was a time when you could park a caravan on the side of pretty much any Connemara road.

Years passed, the tourist industry got its claws into the West, and in the interim the legend of Fisherman’s Blues grew. The album is talked about today in the same breath as Bob Dylan and the Band’s The Basement Tapes; another ramshackle of songs that just work. It isn’t so much 80s rock in dialogue with folk trad, but big music in touch with all the folk of the Western world.

Ireland’s Sonic Answer

Dylan recorded The Basement Tapes in a Woodstock home, adding mystique to the outpost of his Bethel Township. For a time Spiddal was Ireland’s sonic answer to New York’s Bethel: an outpost that could bring sustenance to a once distant metropolis.

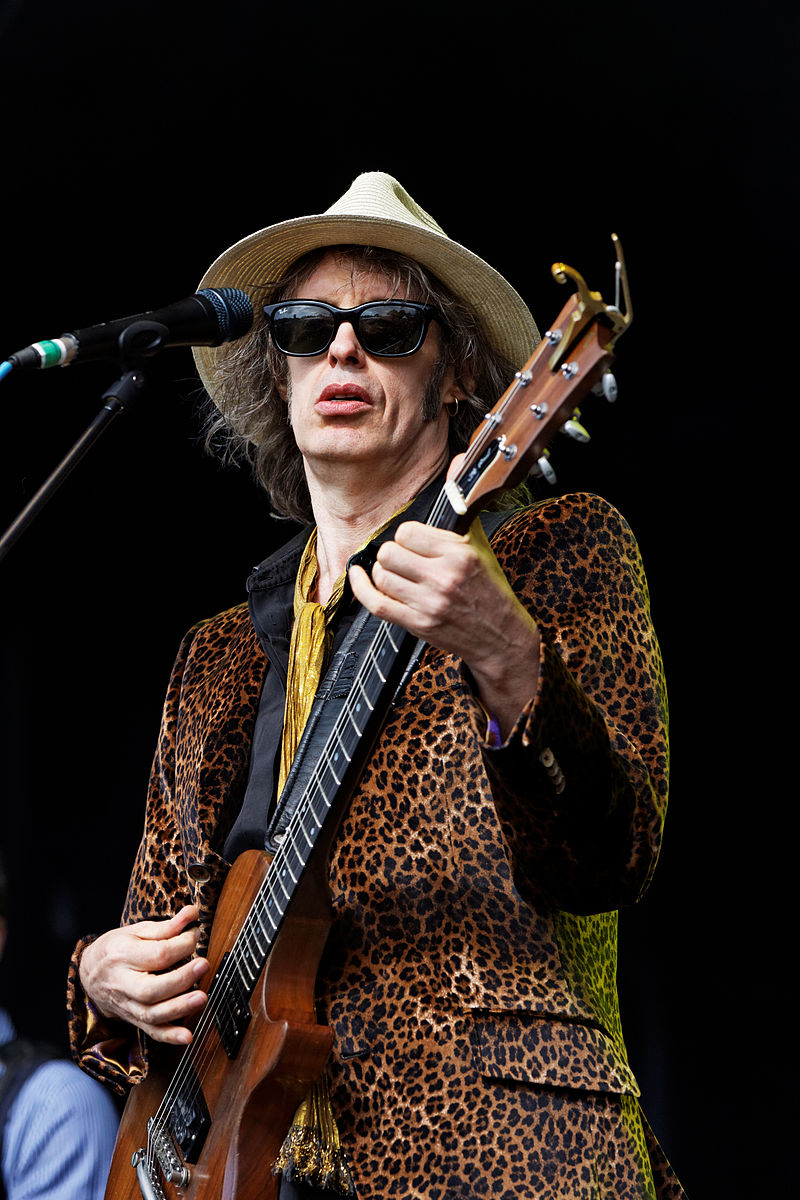

Musicians travelled in and out; from Tuam, Gort to a village integral to the West yet cast off from the innards of urban life. By turning to Spiddal, The Waterboys’ leader singer Mike Scott could tap into the pulses of the West of Ireland, yet still remain in close proximity to the hustle and bustle of Galway city.

Hemmed in, cabin fevered, he could head to the docks, in the hope of chancing on new musicians. Maybe he stumbled to the docks one day and met the Tuam lads I knew, and word began to sift back to the others that myth was forming on the Western seaboard.

Mike Scott in 2012.

A Time Before the Internet

I got back home from Dublin to Murroe, having listened to Fisherman’s Blues on the bus, the music birthing memories of a time before the Internet began its colonization of the imagination.

Listening to the album that day brought me back to a decade when whispers carried from one end of the county to the next, and those awaiting dole day with penniless pockets were served tea free of charge by sympathetic publicans. Tuam, an unemployment black spot, was a place to escape from, and music was the escape before that escape.

The young were looking out towards London or America, with nothing but burned ambition close at hand. The actual song ‘Fisherman’s Blues’ captured the desire to hold on to the older ways of life at a time when Ireland was opening up to the wider world. Oh to be a fisherman, tumbling on the seas, taken in by the sole task of feeding a village back on land. No wonder we disregarded the song: it was a paean to a distant past, nostalgia for a world we were trying to escape.

Tipperary Hills

The album played through as the Tipperary hills gazed back from inside the bus, a markedly different landscape to one where the Atlantic Ocean hovered in full view. I listened to the opening of ‘World Party’ – a song that belittles the claim Scott ditched the ‘big music’ when he arrived in the West – and reflected on its simple championing of the imagination.

‘I heard a rumour of a golden age’ Scott sings, summoning the ghost of W.B Yeats on an album that also includes a rendition of his poem ‘The Stolen Child.’ ‘Don’t settle for reality’ the song seems to say, believe in something greater.

The next day I made my way to the forest that sits at the entrance of Glenstal Abbey beside where I now live; a route I walk each morning with my dog Oscar, listening again to the album on repeat. There was a pink afterglow on the distant Keeper Hill; clouds gave a dusky contour to the skyline that begets the Abbey itself.

Large hedges dwarf the walker of the route, unlike the stretches of Connemara land I associate with Spiddal, along the boreen leading to the trail located within a forest that is a hive of nature sitting in close proximity to Murrroe village.

The forest homes all sorts of wildlife: squirrels, pine martens, foxes, deer that wander down from the hills. Even when the trail is muddy, it dries so quickly it is suitable to walk in all seasons.

The Gatehouse to Glenstal Abbey.

Three Loops

That day and for two weeks after I listened to Fisherman’s Blues in the throes of walking or running along the trail. I listened to specific songs along one trajectory or route, passing the overhanging oak trees, past the stream marking the boundary between the cattle fields and the forest itself. Then I returned to a little inlet in a wall that said I was back at the beginning of the route.

I did three loops of that specific trajectory on the first day, with each song on Fisherman’s Blues synced to play twice in a row; ‘Sweet Thing’ to ‘A Bang on the Ear,’ to ‘When Will We Be Married.’ It was a punch in time to remember a former self.

I remembered hitchhiking along the N17 from Tuam to Salthill as a teenager. I remembered weeks spent on the Aran Islands learning to speak Irish, wondering aloud if the islanders were the same as me.

Locals tell me that the trail as an exercise in boredom; a dizzying mantra of physical exertion. But it is perfect for quiet contemplation.

Some come to record the birdsong at dawn; nature conservationists gather for educational purposes (leaving contraptions to feed the birds at night). The trail is the perfect place to listen to music and walk in peace.

It was December 6th when I went there intent on listening to ‘When Ye Go Away,’ perhaps the most moving song on Fisherman’s Blues, on constant repeat.

The song began to play as Oscar nudged his way through the gates that mark the entrance to the trail from the village path. The trees were shorn of their summer plumage, standing out naked-like in my midst. Winter was everywhere. I knotted my laces to stop from me tripping in mud, and began to walk the first loop with Oscar in tow.

For some reason the same song had stood out from all the others on Fisherman’s Blues. The song soon began to push its intimate waves of affectation down upon me.

On a wild retreat in the Burren Fiona Hanley digs for words, and finds embodied in the Irish language a playful meaning the educational system failed to convey.https://t.co/eRBxGjE7ee@broadsheet_ie @itsmybike @BowesChay @wadeinthewate11 @AliceHarrisonBL @diarmuidlyng @LumberBob

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 15, 2021

Following my Trail

As a song ‘When Ye Go Away’ turns on the phrase ‘fair play to you’ – a kind of mantra. Although cited as ‘fair lady’ on some Internet sites, it is a phrase typical of the West.

I thought of ‘play’ regarding Synge’s Playboy, the way it informs the language of Galway. The phrase comes after ‘in the morning you’ll be following your trail again,’ a line that seemed directed at me.

The lyric seemed to be calling out in my direction, echoing from the forest of Glenstal: I was, as Scott says, following my trail. The echo of ‘fair play to you,’ such an uncommon phrase in the mid west area of Ireland was affecting; in a place where ‘good man’ or ‘go on kid’ dominate the vernacular.

Then the sun came out from behind the clouds and rays of lights ushered through trees, bringing new sensations to bear. I began to step in and out of the past.

I was slowly ushered back in time, consumed by memory. Scott has a poetic skill. He can make meaning dissipate and compute almost simultaneously; the listener grasping his or her context as the bigger one one slips away. ‘When Ye Go Away’ initially read as a lament to a lost lover, a pang to heartbreak, knowing one has gone forever. But as my loops of the trail mounted up, a different context began to emerge from the song. The words ‘your coat is made of magic, and around your table angels play’ gave way to the great lyrical refrain ‘I will cry, when ye go away’ like a memory blow to the gut.

A Mare in Foal

The angels had come in the back door he rarely locked, slowly gathering at the table in the open plan kitchen, as we made our way down the stairs, groggy and still half asleep.

My father was making coffee at the counter and speaking jubilantly about the coming day, talking about the rugby on the telly and the mare that was in foal. One of the angels said the mare would hold onto the foal as long as possible just to annoy my father, interrupting his sleep to make nightly excursions to the stables with flashlight in hand a permanent feature.

‘She won’t give up easy,’ the angel announced, pouring sugar into a cup of tar-like Nescafé coffee. We sat there, angels on our lap, looking out at the green fields in hope the giant hare of Cloondarone would come out to play.

I skipped away from the image of a hare nodding up and down in the backfields. Back to 2021. A cow stared at me from beside an empty ditch. Across from the ditch was the abbey driveway in the distance: a road peppered with walkers. The autumnal-winter colours of the forest contrasted the green field, a blanket of darkness to lose yourself.

The song played through again to ‘I will rave and I will ramble, do everything but make you stay,’ bringing me slowly back to a summer in 2013.

I was entering the time shuttle called memory again. I am parked on the hard shoulder of the motorway waiting for my father to answer the phone. We talk and then, before I know it, I am in Galway city. We are arguing over something one of us had sparked.

Memory brings out the details; a heated discussion walking at the Spanish Arch. I remember the moment I pulled in on the way home to send a text to him, apologising. I had watched him limp up Merchants Road from the Arch that day, his head bopping up and down like the giant hare of Cloondarone. Then he was gone, falling into the Galway crowds like a fish into the ocean.

The sun raised its head too that evening, and the usual boisterous group of students could be heard shouting on the riverbank. There was music and laughter in the air. Then I blinked and I was back in 2021, stupidly worrying that somebody would wander around the corner to see me cry.

Galway Arts Festival, 2007.

II

Even if the sum total of analytic experience allows us to isolate some general forms, an analysis proceeds only from the particular to the particular.

Jacques Lacan.

French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan once coined the term ‘signifying chain’ to explain the relationship between language and the unconscious mind. For Lacan, our experience is knitted into the very fabric of words. And words are sediments like rocks; time leaves a mark on them.

We cannot see the whole sediment in words, even when these words stare us in the face. To give meaning to his insight, Lacan turned to the story by Edgar Allen Poe ‘The Purloined Letter.’ Poe’s story is about a search for a letter stolen from a royal palace.

It is believed the letter – if read – will have detrimental consequences for the personage from whom it was stolen. The police set off in search of the letter, turning the suspect Minister D’s apartment upside down to no avail.

At this point the detective Dupin intervenes, locates the letter, and explains his logic. Dupin talks of the police looking in all places they would think of hiding the letter, when the obvious place to look is the least obvious place: in plain sight.

The letter is located on the mantelpiece. Dupin uses the analogy of a map game to explain his reasoning. Amateurs tasked with guessing the name of a place on a map will usually begin by scouring the smaller regions for the name; nooks and crannies. The easiest way to win, Dupin tells them, is to pick a name – in full view – for all to see.

Lacan reads Poe’s story as a commentary on language and the unconscious. The unconscious is not buried, he suggests, deep in the human organism, like the police think the letter is buried.

The unconscious is language: the symbolic dimension that holds human beings in its midst. It is the context around which words are in play; the time sediment in everyday language. Why we laugh, cry, become elated or defeated, can be understood as the sediment around which words are set. This is why the purloined letter is of such importance to Lacan’s theory of language; it teaches him to look for clues in the words his patients use all the time; words that are in plain sight.

By Mario De Munck – Video still from video Chantal Akerman – Too Far, Too Close. Still uploaded with permission from the filmmaker., CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68641999

Chantal Akerman

One time, when asked why shots of people gathering at train stations populate her film d’Est, the great Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman replied ‘ah that, again.’ Akerman was referring to the Holocaust, of which her parents were survivors.

Crowds populate the long durational shots of East European landmarks in her film, scenes that link words to other words in the everyday lexicon of Chantal’s life.

Her sigh ‘ah, that again’ references what she misses in plain sight. When travelling across the East to make a film about her family’s place of origin, a place they had fled during the pogroms, she moved along her own signifying chain, taking up different positions in relation to a word that dominated her life until her death by suicide in 2015.

The word Holocaust was Akerman’s purloined letter, casting its downward shadow on her life. It was a word her mother was unable to say; her family existed in opposition to. When her mother passed in 2014, Chantal was no longer the child of a survivor, just a child.

Akerman’s words echoed through my thoughts as ‘When Ye Go Away’ played in my earphones and I walked a desolate forest on the edge of a mid-western Irish town. The words ‘I will cry when ye go away’ stood out in plain sight: a letter placed on my own mantelpiece.

The song was no riddle that needed solving. It was a letter perched on the mantelpiece in the apartment called ‘my life.’ I was opening the letter to look inside. I pushed my headphones into my pocket, the dirt rubbing the side of my legs, my woollen hat dripping with wet sweat.

I saw the words staring back at me all the time: ‘when ye go away.’ The words were like diamonds in a sea of stone, signs reaching a destination.

‘Ah, that again,’ I muttered, going back to the memories from walking that day, the song a pedestal from which to stare into a distant past.

I was coming up from a rabbit hole where angels gathered around my father’s table; where we raved and rambled in the hustle and bustle of Galway city. The song was a letter that had been sent to me directly, from the postal office of my unconscious. It was a letter sent to remind me that the ‘ye’ in Scott’s ‘when ye go away’ was a father absent from Xmas again this year. The letter gazed at me just as another Christmas loomed.

Christmas again…

Brown winter leaves crunched under foot, as I began the journey home. It was coming up to Christmas again, and the sediment in words otherwise known as my past was pushing up from the depths of a riverbed. I was making my way home from the trail ashamed that I had lacked the strength to see it arrive.

Not wise enough to see the waves crashing in. Not tough enough to brush them away when they did. Five years, and the waves were still crashing in in unforeseen ways. There was nothing new to be learned from all of this, nothing new to change the course of time. Just ‘that again.’

The Waterboys recorded a follow up album to Fisherman’s Blues inspired again by the West of Ireland titled Room to Roam. To this day, the band’s music retains the influence of the Spiddal decamp; a decamp no longer thought of as career suicide but a pivotal event in the history of Irish popular and traditional music.

One can just imagine a record producer nagging Mike Scott to reconsider his move to the West of Ireland. The producer slams the phone down and turns to his assistant to say ‘I did everything to make him stay.’ An assistant replies ‘not much more you can do.’

Or one can just imagine a mother, speaking in Irish to her husband, lamenting her daughter’s decision to emigrate, to find work she can’t find in Spiddal. The woman says ‘rinne mé gach a bhféadfainn chun í a choinneáil anseo,’ before her husband, glass-eyed with tears, replies ‘silfidh mé na mílte deoir nuair a imeoidh sí ar shiúl.’

Or, yet still, one can just imagine a single mother, struggling to make ends meet in a city engulfed with ‘culture’ – and all the razzmatazz of commerce dressed up as art. She works by day in a factory in Ballybane on the outskirts of Galway city, and spends two nights a week playing in a traditional session in town for extra money.

She dresses her daughter in a hat and scarf and drops her to a West Side crèche before taking a bus that is soon caught up in the suffocating traffic. She will memorise the words to a Waterboys song to play that night in Taaffes. And when she hears the words ‘I will cry, when ye go away’ she thinks of her daughter alone in the crèche.

Or perhaps, as a final thought, one can just imagine a middle-aged brother and his two sisters travelling to Salthill, a childhood landmark, on a cold February morning. The brother drives there from Limerick to meet his sisters at dawn.

They meet in the city and make their way to the prom, parking the car near the diving tower at Blackrock. The brother steps out of the car with a suitcase containing a Bluetooth speaker and an urn. The two sisters follow him on foot down towards the small pebble beach on the right side of the Blackrock swimming tower, past the quadrangle where swimmers congregate, approaching the ocean their father swam in the weeks before his passing.

Coral Beach, Carraroe.

Ashes Fly into the Air

‘I want to play this one song,’ the brother says while fiddling with the speaker, ‘it’s from Fisherman’s Blues. When Ye Go Away.’ His sisters nod in agreement. ‘Yea, I love that song’ they say in sync, like they practiced it earlier that day.

He takes the urn out from the case, holding it up among the three pairs of hands, whispering as they remove the lid. Ashes fly into the air, swirling in a wind that disperses them across a grey-tinged sky.

Music soon begins to mesh with the sound of swimmers jumping in and out of the sea on the other side of the diving tower. Ash and music dance together, as the siblings group hug in one muted silence. The ash soon begins to drift up into the sky, making its way to Aran, Spiddle, and on to Carreroe. Some even make it to Roundstone, across Dog’s Bay, to Ballyconneelly.

A brother and his sisters gaze up at the sky, until no ash can be seen against a grey muzzle of cloud. There is only an urn left for them to cling to, and the shared understanding that life must go on.

Featured Image: Cloondarone, Co. Galway, June 2016.