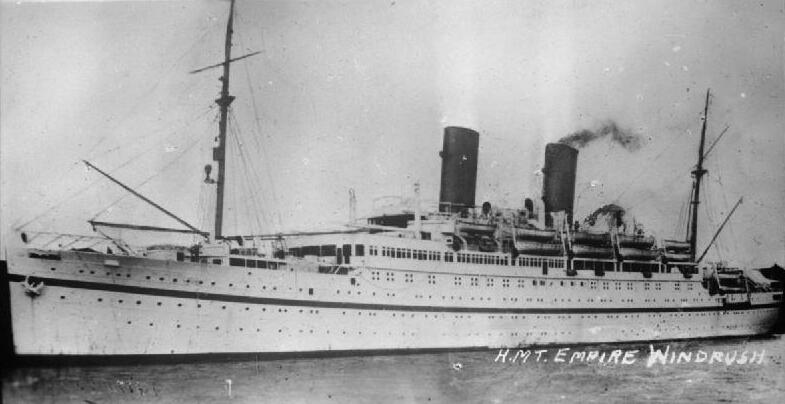

The Empire Windrush sails tonight, she’s got a one-way ticket, and she’s half way home

In June 1948, The Empire Windrush arrived at Tilbury docks in England to the sound of a brass band and hundreds of cheering residents. On board were 802 people, the majority of whom were returning from the Caribbean. Returning, because earlier in the year John ‘Johnny’ Smythe – the father of Dubwiser’s Eddy and John – was charged with accompanying troops from the Caribbean back home after their fight in World War II.

When, on the outward journey, The Windrush arrived at Jamaica, due to severe unemployment and a struggling economy, hundreds of young men could not be given the jobs they richly deserved. The Jamaican Labour officer appealed to Britain for assistance and the Colonial Office contacted Johnny, the senior officer in charge, and asked for him to assess the situation, come up with recommendations and report back. He interviewed the men, categorised them according to their qualifications and abilities and recommend to the Colonial Office that they return to the UK and seek employment.

Anchored off Jamaica, it’s hard to know if Johnny had any awareness of being at the fulcrum of history. He probably just wanted to help the men under his charge out of a dilemma and seized the opportunity.

Two of our fathers sailed on this ship, at different times and in different directions, and they both agreed on two things. First, that it was a beaten-up old rust bucket. The engine regularly conked out and the anchor would have to be dropped for repairs. Secondly that the camaraderie on board was second to none.

The old German boat now acted as a colonial bus service, stopping at every port to take on and put off people, supplies and anything else that could be crammed in. Every corner of Britain’s crumbling empire was represented, every culture, food, language and philosophy. After the misery of the war, it was a chance for ordinary people from all over the world to meet, rejoice, and plan for a better future.

From the lion mountain he came like a storm, Johnny came from Sierra Leone, an African in uniform

Some years before becoming the unwitting catalyst of the Windrush generation. Johnny answered the call from the ‘motherland’ who, after taking a beating from the Luftwaffe, swallowed their pride and sent a call out to the colonies for help. As a ‘Krio’ (descendant of freed slaves) in Sierra Leone Johnny knew what it was like to be an outsider in his own country, so he coped better than some with a sudden immersion into Scotland in winter and RAF training.

Shot to the right, shot to the left

from ‘Johnny’ by Dubwiser.

He ended up as a navigator on Stirling bombers. The only black man in his squadron, he became a talisman for the others. Life expectancy was very short and during the latter part of 1943. On average planes were shot down every five to seven missions.

In November 1943, Johnny was shot down, badly wounded, captured, brutally interrogated by his captors, hospitalised and further interrogated in Frankfurt before being sent to a POW camp.

There, he joined the escape committee, but never tried to escape, as he pointed out that a six foot four inch black man wouldn’t get very far in North Eastern Germany. After eighteen months in the camp, on a morning in 1945 he and the other inmates awoke to find the guards gone and the gates wide open. Russians appeared two days later and they were liberated.

340 years ago, Colston was a slaver-oh, they covered it up, but still we know, now the truth is rolling down the road

Like it or not, statues have power. They point in a direction, usually the one which the commissioners wanted to point in. Bristol was littered for hundreds of years with the name of it’s ‘greatest son’ Edward Colston. Known still in our lifetimes as ‘a great philanthropist’ who, childless, left a lot of his colossal wealth to the city of Bristol.

We aren’t interested in the argument that that was ‘a great gesture’, worthy, indeed of place names and a statue in the city centre. The money was not his to give. The wealth that he created came from the slavery of 80,000 souls. He made the people smugglers who ply their bloody trade across the Mediterranean and the English Channel, look like amateurs. This man was a mass murderer. He gained a fortune and a statue, and in return he reaped genocide.

On the June 7, 2020 Jonas’s son Josh received a message on his phone: There was a big protest happening down at Bristol city centre. He hurried down there in time to see a huge crowd dragging the statue of Colston down towards the cut. He sent his father a photo, who had the sense of a long loud cheer going up across the country. As in so many things, young people were leading the way. Resistance to everything Colston stood for had been building in Bristol over a long period. His time had come and now he lies, battered and bruised, in a museum where he belongs.

A gal from the Caribbean… What an amazing woman!

After the great and ignominious, it’s useful to return to the small. Alexandrine (Spider’s mum) was a small woman, but like so many of the Windrush generation, she was strong. Eight years after the Empire Windrush sank in the Mediterranean, she was invited to come to England after passing a test demonstrating her skills in sewing, cooking and auxiliary nursing.

She left everything, her whole life in Dominica and came half-way across the globe to a country that was becoming less and less welcoming to ‘her kind’. But she knew what she had to do and she saw something in London, a glimpse of a larger potential world, if not for her, then perhaps for her children?

So, she worked, raised her children, worked some more and she kept going, kept doing, through thick and thin. In Dominica her skills as a calligrapher were noticed by Catholic nuns and in England she also learned to type.

In time Alexandrine managed to get a post as a pastry chef at The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. As the years went by she ensured many others in her circle of family and friends could also get work there, each according to their abilities. She made it her mission to help those who were in turn helping others.

After a generation of work, play, child and grandchild rearing and making what was agreed to be the best curry goat and black pudding in East London, Alexandrine returned to Dominica at the age of forty-four.

From there she sent pictures of herself smiling broadly under a coconut or banana palm and returned to the U.K. every year in the Autumn (to avoid hurricane season) with bags of produce and stories from back home. The beauty of a life well lived is unparalleled. Across Britain, this story is being retold by mother after aunty after grandma. This is our small and unsung legacy, inspiring us to live our best life.

She did, she did, she did and she keep on doing

From ‘Amazing’ by Dubwiser.