For a number of years now, I’ve been convinced (too fervently, in the opinion of some of my friends!) that Lana Del Rey ranks among America’s most challenging and skillful of contemporary wordsmiths: a singer-poet with a unique (and often unsettling) talent for cultural imagining.

Stylish, intelligent, irreverent, and vulnerable, her music packs a poetic punch, while also drawing on traditions of literature, film, and popular song, ranging from Bruce Springsteen’s glimmering highways of folk-rock to the Beat generation’s boundary-breaking visions of an embodied (and renewed) American spirit.

What “I really got from [Allen] Ginsberg was that you can tell a story [by]painting pictures with words”, Del Rey has said of her early song-writing practice: “It just became my passion immediately, playing with words and poetry”, as a means of personal self-definition. The result has been a body of literary-musical work at once socially subversive and emotionally profound.

If Arthur Penn could envisage Bonnie and Clyde as icons of a generalised counter-cultural romance in the mid-sixties, painting the seductions of sexual liberation against a lavish panorama of eruptive killing, Del Rey’s albums adopt the motifs and then test the limits of that project (and projection), weaving the visceral mythologies of youthful passion and big dreams into a tapestry, scorched and frayed at the edges, of insidious and often compulsive “ultraviolence”. “He hit me and it felt like a kiss”, simmers her song of that name.

And lest we mistake such provocations for a merely personal fetish, we’re reminded of America’s own deep-running attachment to such obsessive fantasies. “Blessed is this union”, Del Rey lilts: “I’m your jazz singer, / And you’re my cult leader, / I’ll love you forever.” On “the dark side / of the American dream”, harm can seem heavenly, and the visions of art become entangled, intimately, with the realities of pain: Ultraviolence.

Some critics have objected to this album, interpreting it (and her work more broadly) as a glorification of domestic and patriarchal abuse. Others have accused Del Rey herself of misogyny, infantilising her female personae and reinforcing an already pernicious culture of male intimidation and exploitation against women. For all their persistence, however, these critiques frequently misread (or miss entirely) the complexity of cultural portraiture that Del Rey is attempting.

Del Rey’s back catalogue stands as a tour-de-force in self-invention, but also offers a subtle (and disturbing) diagnosis of the society she claims, always, as her own – “like an American.” “Elvis is my Daddy, Marilyn my Mother”, she says, in an artistic gestalt both parodic in its appropriations and compelling, in its assurance: “Jesus is my bestest friend.”

In the USA, that most image-saturated and fame-hungry of republics, Del Rey is a symbol striving to become a myth – in which we see ourselves in a new light, dreamily nightmared. “Every time I close my eyes”, she sings (partly in tribute to F. Scott Fitzgerald), “It’s like a dark paradise.” To condemn Lana Del Rey, the singer posits, would be akin to renouncing America itself, love it or loathe it.

Del Rey, of course, famously featured on the score of Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, crooning a two-dimensional, Daisy-esque plea to be loved forever “like a little child.” In its complicated glamour and wounded awareness of the pitfalls and attractions of “burning at both ends”, however, her work may be seen to inherit and examine (with an equal intensity) those same concerns dramatised by Fitzgerald, not to mention Enda St Vincent Millay, the originator of that smoky apothegm:

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

There has always been more of Gatsby (whose most usual reiteration has resembled Don Draper in Mad Men) than Daisy in Del Rey’s song of herself, despite what her detractors may suggest. Like her, Fitzgerald’s titular everyman is, fundamentally, nobody special, who created the name, wealth, identity, and charisma he is mythically remembered for: something from nothing, and in his case, all for a long-gone lover, out of the past. Lana Del Rey likewise is a carefully curated, highly stylised, all-encompassing fiction (invented by Elizabeth Grant) – a romance, but one at the same time more palpably real than pop music, her chosen genre, can traditionally contain.

There’s a comparable sophistication of psychological portraiture in the work of both figures. The triumph of Fitzgerald’s late masterpiece, Tender is the Night, is not the protracted revelation of Dick Diver’s inner life and escalating crisis, which so fills the novel, but the later, briefer revelation of Nicole’s astute ability to see and dissect the manipulations and (self-)deceptions of her magnetic husband for what they are. Unbeknownst to him, she notes

[how] something was developing behind [his] silence, behind the hard, blue eyes […] it was as though an incalculable story was telling itself inside him, about which she could only guess at in the moments when it broke through the surface. [She saw now that] his eyes focussed upon her gradually as upon a chessman to be moved; in the same slow manner he caught her wrist and drew her near.

Del Rey’s music shines with similar moments of life-altering clarity, seeing in the heroic other she once loved the havoc of destructions he, or their relationship, has become. “But I can’t fix him, can’t make him better, / I can’t do nothing about / His strange weather”. Her songs are dramas of mutual recognition and breakdown, of shared compulsions and irrevocable severance, or what Robert Lowell called (in his own poetry) Life Studies.

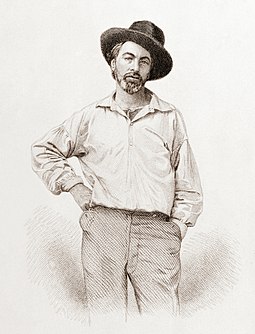

It is typical of Del Rey, moreover, that she can cite – too blithely, in the view of some critics – both Sylvia Plath (in “Hope is a dangerous thing…”) and Billie Holiday (in “The Blackest Day”) as inspirations for her own work, which also includes a cover of a track made famous by Nina Simone, “The Other Woman”. “I contain multitudes”, she has said, quoting Walt Whitman – and it is perhaps this audacious hybridity that generates the aura of authentic originality that surrounds her work.

Whitman himself is a resplendent ghost, looming at the margins of Del Rey’s amatory vision. “I Sing the Body Electric” is a direct quotation from his poetry, while “Music to Watch Boys To” might be taken as a riff on that section of “Song of Myself” in which a woman (a stand-in for the author) experiences a sensation of powerful erotic arousal when watching “Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore”.

Walt Whitman.

Del Rey’s song, similarly, is suffused with sexual desire – albeit prefaced by the vital, and conscious, assertion, “I know what only the girls know” (emphasis mine).

The same recognition, both vulnerable and electrifying, deepens what would otherwise be the merely referential adaptations from Leonard Cohen elsewhere in her repertoire: when she embraces his (male) mantra as her own, “I’m your man”, and in offering her own haunted rendition of “Chelsea Hotel, No. 2” (which recalls a now-estranged lover “giving me head / on the unmade bed”). Far from perpetuating the presumptions of “the male gaze”, or solidifying its social perceptions, Del Rey subverts its power, wielding it for her personal self-expression (as one of “the girls”).

Relatedly, the blend of ecstatic remembrance and heart-sick yearning that pulses through Del Rey’s music has, at times, an explicitly religious (if also somewhat Nietzschean) dimension. “Faith, don’t fail me now”, as one prayerful, foreboding love song has it: even though, as star-split lovers, “we were born to die.” To wander for any length of time among Del Rey’s American monuments is to witness the singer herself repeatedly reaching for and casting off the old idols, in an atmosphere of passionate sexual and self-awakening that might, we’re lead to imagine, suffice where a previous “faith” (or love) has indeed foundered. “God’s dead, / I said: baby, that’s alright with me”, rings one propulsive credo. “When I’m down on my knees, you’re how I pray”, eddies another. And for the huddled, nameless voyeurs, her listeners (whose apparently insatiable “groupie love” hovers as a backdrop to all her songs), Del Rey reserves a glancing blue note: “Walk in the way of my sweet resurrection”.

As here, for all her sardonic self-awareness, Del Rey seems to claim De Profundis as an unspoken motto for her music: a cry “out of the depths”. When her shadowy voice rises – in a sudden, sky-coloured lift – with the plea and invocation, “Let there be light”, we believe not only in the force of her desire but in the power of song itself, to utter our truths.

Lana del Ray in 2014.

Her persona also displays a Wildean flair, a delicious ease, in skewering the prevailing moral codes and injunctions of her society. Del Rey expresses, with a kind of controlled but abundant intensity, what she sees as the psyche of American life, with the result that we can glance if we wish to, in the falling crystal of her music, what political militants have called the system, with its permeating paradoxes and devastations.

Del Rey frequently appears as both prophet and survivor of a Beat-like realm of experience, lived on the edge (or “on that open road”, as she has it), known only to the beautiful and damned. “In the land of Gods and Monsters / I was an angel”, she moons, “wanting to be fucked hard”. In her words, Del Rey is the self-described product – in the full and possibly uneasy sense of that term – of “a freshman generation / Of degenerate beauty queens”:

With our drugs, and our love,

And our dreams, and our rage,

Blurring the lines

Between real and the fake…

Latent cultural pieties concerning (female) sex and celebrity, individuality and personal choice, are deployed and then exploded; whenever Del Rey looks in the mirror, we see all of America in vivid close-up, simultaneously trapped and liberated in a dream-landscape where drifters survive by “living like Jim Morrison”, made “degenerate” and luminous by yearning.

Barry Delaney travelled deep into America in the wake of Trump's Presidential victory. He shares this precious archive with vivid descriptions.https://t.co/xo5LPiC9tu@broadsheet_ie @MarcKilkennyArc @ConorBlenner @itsmybike @think_or_swim @LumberBob @looplinefilm @NMcDevitt

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 2, 2020

Part of what makes this extravagant concoction so fascinating is the combined subtlety and hellion irreverence with which the singer-songwriter theorises (and questions) the meaning of her own star-power. “Life imitates Art”, she declares, before exploring the full implications of such a behavioural pattern, in songs (like those above) as beguiling in their soundscape as they are troubling in the vistas they evoke – where culturally approved aspirations (towards fame or material self-satisfaction, for instance) can dissolve in bathetic fantasies at once lurid and seductive. “There’s nothing wrong”, she chants, as we find ourselves “contemplating God / Under the chemtrails over the country club.”

This is a music that sets out, with an appropriately expansive sense of cultural ambition, to dismantle and then re-conjure the edifice of American civilization in its own image, soaring to celestial heights of song and emotion, as the hell-fires of contemporary history burn on. “I can see my baby swinging”, Del Rey sings, in sweeping glissando: “His parliament’s on fire, and his hands are up.”

The potentially destructive fevers of young love are likened to, indeed are made to encompass and elucidate, the act and aftermath of a failed rebellion, in an image that also calls to mind the USA’s (literally incendiary) geopolitical relationship with Central and South American nations. Amid the ruins of a vaguely defined but still palpable political cataclysm, the cries of revolution are distilled down to a sultry whisper – for Del Rey, their essence – “I’m in love.” “Real love”, we likewise learn elsewhere, “is like smiling when the firing squad’s against ya, / but you stay lined up.”

And yet, the mythological potency of such images is counteracted by competing narratives, streaming through the work as a whole, of quest and longing, which elaborate, in turn, Del Rey’s self-styled brand of American hope. “I’m still looking for my own version of America,” she sings, drawing on both John Lennon’s “Imagine” and Simon & Garfunkel’s “America”: “One without the gun, where the flag can freely fly.”

While the atmosphere that most lingers in and around these tracks is of cinematic nostalgia, the intensities of past (or lost) intimacy montageing with the possibility of a redeemed, future love, the tone is in fact remarkably flexible, varying from elegaic to playful. “God Damn Man-child”, is the headline (the opening lyric) of Norman Fucking Rockwell!, a Trump-era album that may be read as a sometimes bemused, often probing investigation into American maleness and its social manifestations. “I watch the guys getting high as they fight / for the things that they hold dear”, Del Rey observes, adding characteristic nuance to the scene: “[as they fight]to forget the things they fear.” “There’s a new revolution”, we hear in another, more unsettling track, attuned to the #MeToo movement and its critique of an entertainment industry dominated by powerful, exploitative, and sexually rapacious men – a culture, in her words, “born of confusion / and quiet collusion / of which mostly I’ve known”:

Cause I’ve got

Monsters still under my bed

That I could never fight off

(A gatekeeper carelessly dropping

The keys on my nights off).

Such candid, emotionally complex confessionalism, and with regard to so intimate (and apparently traumatic) an experience of “gatekeeper” culture, arguably problematises critical arguments that cast the singer either as an apologist for patriarchal systems, or “tone-deaf” to the concerns and testimonies of women survivors. If anything, Del Rey has been consistently vivid and challenging in her portrayals of the music business – as well as American life more broadly – and in her capacity both to articulate and critique the promises of “Money, Power, Glory” that fuel it. “I Fucked My Way Up to the Top” can be understood as a deliberately inflammatory declaration of artistic self-fashioning, but also as a retort to a professional media prone to judging and dismissing female artists – an example of an indomitable diva taking ownership of the demeaning stereotypes and derisory language used against her.

“Hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have”, Del Rey sings, in almost a whisper, “But I have it.” Her music subverts the preconceptions and prejudices of the narratives (concerning love, femininity, power, and song itself) that underpin Western modernity, even as it translates their key appeals into a new register of cultural emotion.

Listening to Lana, we see America’s most deep-rooted degradations and exultations writ large; but we also learn to view life itself as a lover’s covenant, demanding that we intuit, and then go on to risk, the shining path before us – leading, perhaps, to a more shareable world. “No bombs in the sky (only fireworks, when you and I collide): / It’s just a dream I had in mind.” Long may the dream continue.