When it comes to veteran rock journalists, few could lay more genuine claim to the title than Allan Jones. After joining Melody Maker as cub reporter in 1974, with no previous writing experience, but an application letter which concluded: ‘Melody Maker needs a bullet up its arse. I’m the gun – pull the trigger’, he rose to editing the magazine ten year later. On leaving the fabled inky at the height of the excesses of Brit Pop – about which he was less than enthusiastic – he founded and edited Uncut, providing a British-based forum for the emerging Americana/New Country scene. Now in semi-retirement, he has produced two volumes of rock’n’roll anecdotage – 2017’s Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down, and the recently published Too Late To Stop Now. Des Traynor caught up with him to discuss these and sundry other matters at last year’s Kilkenny Rhythm’n’Roots Festival (a.k.a. ‘the best little weekend music festival in Ireland – and the known universe’), now celebrating its 25th anniversary.

It seems like there are more lengthy pieces in this book than the last one?

Yeah, partly due to the circumstances in which it was written. The first book they were interested more in a compilation of the stories as they were already written, and I didn’t really think of elaborating on them. I just packed the book with as many stories as possible, which meant that a lot of them had to be shorter than they could have been. I started writing stories for the second one just at the beginning of the first lockdown. As I explained in the book, I thought people would be using their time productively – you know, learning the harpsichord or how to juggle or a foreign language, whatever.

You didn’t want to emerge empty-handed?

Yes, I mean, I could quite happily have spent lockdown getting stoned and watching Netflix, there’s loads of movies. I’ve got a link to the BFI player. So, endless hours of viewing available, and a vast record collection I could reacquaint myself with – but when I started writing the stories there was no inhibition in terms of words, so I tended to let the stories dictate the length they would be.

Were you always confident about your own abilities as a writer and critic, or did you feel like maybe you were a bit out of your depth when you started?

I had loads of opinions. I wouldn’t call them well-informed in a lot of instances, but they were opinions and I wasn’t shy about sharing them. That came out of an Art School background. If there was one thing that Art School taught me, it was that you had to stand up for your work and your opinions, and be unfazed by criticism. So I hadn’t realised that at the time, but it did give me a lot of confidence, more bravado and bluff really.

But you could do the work?

It was very simple. I wasn’t stupid. I’d read Melody Maker for years. I’d recognised the basic template of writing a 2000 word feature on somebody who’d just had a chart hit. You went in, you established the fact that they had a new single, let them tell you how it was different from the last single, how it was a step forward, how it was a new vision for the band or whatever. That usually took about five minutes. To liven things up, you’d hope that one of the band’s chart rivals had a new single out. So you’d ask them for an opinion on that, hopefully it would be a bit controversial, they’d slag it, which would give Ray Coleman the chance to put a big headline on the cover: ‘Sweet slam Rubettes’, or ‘Shawaddywaddy slam Glitter’. And all they would say, basically, was ‘I’m not really keen on it’, or ‘It’s not very good’. But that was enough: that stirred up a bit of controversy.

The other thing I learned to get a band talking was to tell them that you’d heard a rumour that one of them was leaving, or doing a solo album. And sometimes they’d go: ‘How did you know that?’ ‘Oh, just a wild guess.’ But it would get them talking about band dynamics. But I found that, a band like Mud for instance, who were really sweet guys, they were used to churning out these interviews, very pat answers. They weren’t really engaged with the interview process. But if you stopped for a drink with them, after they got this contractual obligation out of the way, I’d start asking them about their early days: anecdotes galore! Fucking brilliant stuff! Les Gray: really a very funny man. So I started to introduce some of those anecdotes to change the shape of the copy that was expected. At first they’d just get cut out, ‘Stick to the news story that you’ve been sent to do.’ So I just started to fracture that as much as I could. And although I hadn’t read Lester Bangs or people like that, I had read Tom Wolfe, and I’d read Hunter S. Thompson. I had an idea of what the new journalism was: contravening traditional journalistic rules about not involving yourself in the story. So I started introducing myself as a character. At first, they were the bits that would be cut. But as I became more successful at that kind of integration, the opportunities opened up. I mean, at that time, I would accept anything they asked me to do. I’d never written before, and I had to learn how to write well and quickly. So ‘I’ll do anybody, just send me out, I’ll do it. I’ll come back and I’ll write it up and see where we go from there.’ And once as the readers’ responses started to come in…

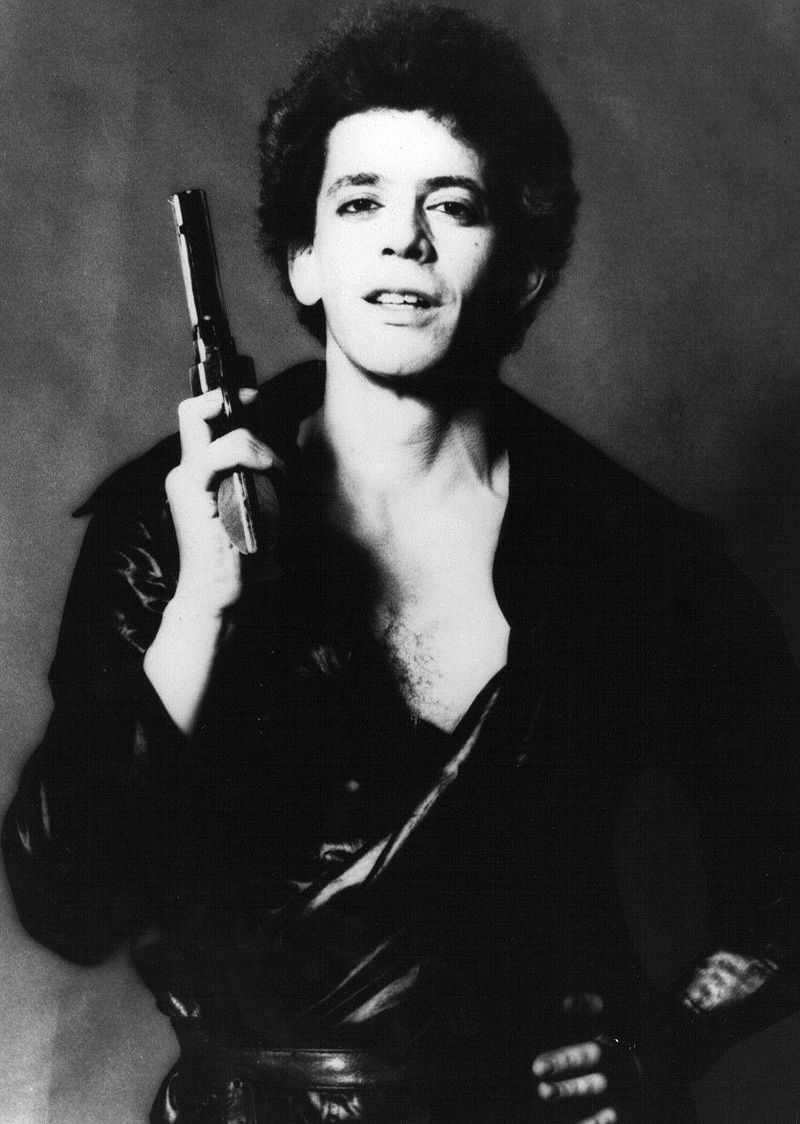

Lou Reed in 1977.

You hit it off with Lou Reed?

How extraordinary was that? I could have wept. I was such a huge, huge Velvets’ fan.

Why do you think he took a shine to you?

When I walked in, with some presence of mind, I pressed record on my tape recorder. And for twenty minutes there was just this torrent of abuse. His first words to me were, ‘Do you know your head is too big for your body?’ And ‘What toilet did Melody Maker find you in, faggot?’ It was effortless on his part. It just went off. But I was just laughing. This was the Lou Reed I wanted. I could feel the piece writing itself. And I thought even if he tells me to fuck off when he’s finished this tirade, I’m gonna have enough to write something.

I then took a breath. And I just said something like, ‘Are you doing this because this is what you think I expected Lou Reed to be like? Or is this you being Lou Reed? Or are you just turning it on because, you know, you think this is how the public want to see you?’ And he thought about that, and he said, ‘Sit down’. So I sat down, and he said, ‘Drink?’, and pulled out a bottle of Johnnie Walker Red, the first of two that we got through that day. I think, because I had a sense of humour, and I wasn’t intimidated by him, he just liked it. And I wasn’t deferential to him, and I think he liked that as well.

And at the end of the interview, when the chief of press came in, Lou said, ‘By the way, book Allan into the hotel I’m staying in in Sweden. You’re coming on the road with me.’ And I thought he’d forget about it, but come the next Tuesday, there was a fucking limo outside my flat, drove me to the airport, got on a flight to Stockholm, there was a car waiting at Stockholm airport, took me straight to the hotel, and Lou is waiting in the lobby, saying, ‘Where have you been?’

What about Van Morrison, whose music you obviously love, but all your encounters with him were ‘difficult’.

Well, the first one especially, it was backstage at Knebworth, not ideal. He’d just come off stage, in a sulky mood. In the end, I just said, ‘Fuck it, man. If you’re not gonna chat, you know, we’re wasting time. I’ve got things to do, you’ve got things to do, I’m gonna leave.’ I was fuming, absolutely fuming. But I must say it never dented my admiration or love for his work. His work transcends any personal faults that he has, and to this day it does.

He is a paranoid fucker.

He’s always been like that. People who know him better than I would will trace it back to the way he was treated in the early part of his career. So comprehensively ripped off that he just hates the music business, which has offered him such success. So I can understand that level of bitterness. But five minutes in the presence of virtually anything that Van’s recorded, and any kind of negative thoughts that I have about him as a person immediately evaporate. I saw four gigs over three months, that they played just after COVID, at the Palladium, Hampton Court, a small Dingwall’s gig he did, and then at the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane. And he was just incredible each time, absolutely astonishing.

Over lockdown Dara Waldron grew fascinated by the 1921 killing of Winnie Barrington. This chimed with Van Morrison's music and led to dreams of a journey North.https://t.co/4lzMnojmB3@vanmorrison @dineensparish @BowesChay @BenPantrey @corourke91 @danwadewriter @Nialler9

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 21, 2022

Do you think that there’s a lot of compromise in reviewing now, that rock journalism has become an extension of PR?

Well, I think that is true to a certain extent: it’s certainly not the kind of confrontational journalism that I became attached to. Also, the idea that the writer as a character becomes involved in the story isn’t much encouraged, it seems to me, from current reading of Mojo or Uncut. There seems to be a greater deference to artists these days.

Are there any younger writers now that you particularly like?

I don’t read so much that I could say. But here’s a point that addresses your thinking about the PR nature of it, and the way the writing has changed since my days. I can read a whole issue of Uncut, and if it didn’t have byline names on the page, I wouldn’t really know who had written it. They really are quite interchangeable. There is a template that everybody adheres to. It’s not compromising the features, which are good in themselves. But what I miss is an individual, indeed, an idiosyncratic, voice. It’s just not there. However, there’s a writer in Uncut called Damian Love, who I really, really like – probably because his taste and mine are really similar. And another writer who doesn’t appear as much as he should in Uncut, because he’s got a separate career as a political commentator and broadcaster is Andrew Mueller, who has written a couple of very, very good books – one about his life as a political foreign correspondent, and the other a memoir of his career as a music journalist, including coming over from Australia.

I really enjoyed the books, not just in terms of subject matter, but because they are so funny, especially the way you often describe things in exaggerated terms.

Well, I think that came out of not having any musical training and not knowing anything about musical theory. So I can’t break down a piece of music into something well informed about the actual musical content like, you know, Richard Williams was able to do, in the old Melody Maker.

Did you ever try learning an instrument, or playing?

No. At school – first year, comprehensive – we had to do music as a subject, and apparently to get good grades in that exam you had to play an instrument. And it wasn’t the kind of school where you wanted to be seen carrying a violin. So I thought: what comes in something square that looks like it’s a suitcase? So I ended up supposedly learning the trumpet. But when I went to the first lesson and I just couldn’t a noise out of the fucking thing. I was just blowing and blowing, I believe so hard that I burst a blood vessel in my nose and had to be taken to hospital. So I never went back for the second lesson.

The end of your musical career.

Indeed.

And with that ripping yarn, so characteristic of the man, he’s off for a fun-filled afternoon with his old mucker, B.P. Fallon.

Too Late To Stop Now: More Rock’n’Roll War Stories was published by Bloomsbury, on May 25th. Available in all good book shops.