When I was sixteen I gave up learning the piano. In her report my music teacher (who had terminated my studies) wrote: ‘what an awful shame’.

The story is a common one. Young peoples’ lives become filled with music on records, video, in films, on radio and TV, during Saturday nights, in supermarkets, in amusement arcades, on the streets and in concerts. Culturally exploded thus, they sit down to Mr. Beethoven and wonder what on earth this glaring composer from the distant past has to do with the rhythms they feel and the harmonies they hear.

When I left school I was drumming on a local pop group and living at home, sleeping till lunchtime. I hadn’t qualified for university and my father wanted me to get a job. I remember replying in writing in answer to an advertisement for a shop assistant and saying that my hair was long and I wouldn’t get it cut. I only had the music. I used to sit at the piano for a few hours each afternoon, improvising.

Pop band The Unkind with drummer Roger Doyle (centre)

The Royal Irish Academy Of Music

Over a period of months I gradually composed a four-page piano piece and showed it to my former piano teacher. She suggested I contact Dr. A.J. Potter in the Royal Irish Academy of Music. I played my four-page piece for him; he had a vacancy and the following week I started composition studies with him – once a week for an hour. From then on I had to have something composed for every Monday afternoon.

Dr. Potter never said ‘you can’t do that’. On the other hand he never told me exactly what to do. Maybe this was his approach. We talked about life and art and he gave me the musical space I needed. He said you could read all the books you liked about instrumentation but if you really wanted to know how a trombone works you should buy a trombonist a drink after the concert. He never encouraged me and I needed a little.

After a year at the Academy I submitted my compositions for the Junior Composition Scholarship which would mean a year’s free tuition. At the beginning of the next term I received a phone-call from the office of the Academy: ‘With regard to your recent application for the Junior Scholarship in Composition we wish to inform you that you have been successful in…’. I had never planned on being a composer; necessity was the mother of my invention.

I wanted to write a piece for orchestra in my first scholarship term. Dr. Potter said: ‘Well go ahead!’. I had a drawing of the highest and lowest notes of each instrument in front of me as I composed Four Sketches for orchestra. It took me five months and was later performed, when I was twenty two, by the Dublin Symphony Orchestra (because it won second prize in its competition for composers), and the RTÉ Symphony Orchestra (the National Radio/Television orchestra).

The first radio broadcast of any work of mine was of Four Sketches. In 1969 at the end of my second year at the Academy I was awarded the Vandeleur Scholarship in Composition. During my third year I began experimenting with my tape recorder at home in my search for new sounds and compositional approaches. I took to tape music like a duck to water without ever being bothered about the ‘do you call this music?’ syndrome. I never stopped and thought too much – I just did it.

When I first heard tape music (loosely termed electronic music) on record, it was as though it had been brought back to me as a memory. It was strangely familiar. It was what I was looking for.

The next time I submitted taped works to the Academy, I wasn’t awarded the scholarship. Since the Academy only had a cheap mono tape recorder and I needed a recording studio I thought: ’Three years is enough’, and so I left. The Academy is not a University so there was no degree to get even if I had stayed I was twenty one and still sleeping till lunchtime.

Utrecht

Soon after, a small record company in Dublin promised to bring out a record of my music, recorded some of my pieces, and then went bust. Then in 1974 I was awarded a Dutch Government Scholarship to enable me to study electronic music at the Institute Of Sonology at the University of Utrecht. This changed everything. In Holland I had the chance to come in out of the cold and join the stream of European avant-garde music. I attended three weeks of the World Music Days Festival in five Dutch cities.

At the Institute Of Sonology in Utrecht the students had to complete fourteen studio exercises before they were allowed to submit a compositional or purely technical project, to a committee which would decide if it was ‘of sonological interest’ (sonology is the study of sound), or not. It took me ages to understand the principles of how the studio worked, about voltage control, amplitude modulation etc.. I was the last to complete my fourteen studio exercises. In the second term I was allotted twelve studio hours per week in response to my project, all on my own. I used to get heart poundings opening the door of my allotted studio – one of the best equipped in Europe.

I began a new composition using almost entirely electronically generated sounds for the first time. This

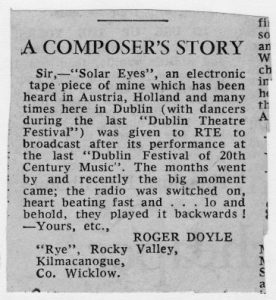

piece later became Solar Eyes, which was broadcast backwards on Irish radio.

Letter from Roger Doyle to the Irish Times, July 1976 (courtesy of the composer)

During the Easter holidays I got a great idea: why not bring out the LP myself that had met such a disastrous fate a year earlier – the covers had already been made and were sitting at home. I had saved enough from the scholarship spending money to be able to do it. I sent to Ireland for the recordings of my instrumental pieces and set about making copies of my tape pieces in the Institute’s studios – revising a section of my piece Oizzo No in the process, improving it immensely.

I took my new master tape to Phonogram in Amsterdam and asked them to make me 500 records and gave them the money. When I told them I couldn’t afford a test pressing they said: ‘don’t worry Mr. Doyle, we’ll keep trying till it comes out ok’. And they did, and it did.

I wanted to cover up the name of the record company that had gone bust, on the back cover, so I had 500 new backs printed with some new information on them, which I began to stick on individually with glue over the existing ones – thus becoming the first composer in the history of the world to stick his own record covers together. I was twenty five and had a record of my own music out, called Oizzo No.

I shipped them off to Ireland and sold one to a customs man at Dublin airport on my arrival home. I had to sell 330 copies to break even, which I did after two years.

‘The Curious Works of Roger Doyle’ documentary (directed by Brian Lally) is being shown in the Mermaid Arts Centre in Bray on 17 April. Tickets available here: https://www.mermaidartscentre.ie/whats-on/events/the-curious-works-of-roger-doyle

For more on Roger Doyle’s work see: http://rogerdoyle.com/

Bandcamp: https://rogerdoyle1.bandcamp.com/