In how many garrets and non-garrets of the world

Are self-convinced geniuses at this moment dreaming.

Álvaro de Campos, ‘The Tobacco Shop’, 1928

In the early days of the Internet – end of the 1990s for me – while a history student in UCD, a friend took a passionate interest in a volatile political situation beyond Ireland’s shores. Although aroused by injustices perpetrated by both sides, the drama itself also seemed to be a source of entertainment. He participated, in a small way, by adopting email aliases that represented varying, even opposing, viewpoints.

In a time before the arrival of a fully-fledged ‘social’ media, friends might call into his smoke-filled non-garret room to find him participating in online fora. There, we might encounter bursts of laughter and guffaws – to the bemusement of anyone lacking an intimate understanding of his predilection.

These were not simply pseudonymous accounts. In creating and projecting characters that seemed to reflect his own uncertainties my friend had, unconsciously, adopted a version of a dramatic form of communication – the heteronym – invented, or at least fully realised, by the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935). This approach is of enduring interest given the extent to which multiple selves prevail in online communication, including in the common use of anonymous handles on Twitter that often depart from a primary, mild-mannered self, into a more transgressive, ‘other’ personality.

A new, ground-breaking biography of Fernando Pessoa in English by Richard Zenith, Pessoa: An Experimental Life (Allen Lane, London, 2021) brings into the mainstream – to the English-speaking world at least – a Portuguese poet, whose extraordinary capacity for invention, sensitivity to language, and, ultimately, attention to human liberation places him in the highest echelon of a discipline he recast in his own images.

Moreover, unlike other Modernist writers of his generation, Pessoa is profoundly accessible. As Zenith puts it: ‘We don’t need to look up words, hunt down references, or read up on some period of history or current of philosophy to follow his poetic trains of thought and feeling. (p.324)’ Indeed, Pessoa expressed reservation regarding the art of James Joyce, which he described in 1933 as ‘a literature on the brink of dawn’ that was ‘like that of Mallarmé… preoccupied with method. (p.831)’

Pessoa was inspired by aspects of the Irish Literary Revival of the early twentieth century, and even drafted a complimentary letter to W.B. Yeats, whose esoteric tastes he shared. However, as Zenith puts it, lacking Yeats’s ‘grand ambitions and conviction, Fernando Pessoa was more like a jazzman of higher, occult truth, improvising on standard doctrines of the esoteric repertoire and introducing his own variations, without staying in any one place for long. (p.849)’

It is the combination of Fernando Pessoa’s simplicity of expression and an apparently endless capacity for experimentation that make him such a valuable guide to our confused and uncertain time.

Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

The Heteronyms

The poet is a feigner

Who’s so good at his act

He even feigned the pain

Of pain he feels in fact

Fernando Pessoa-Himself, ‘Autopsychography’, 1931

Distinguishing pseudonymous works from heteronymous works in 1928, Pessoa wrote that ‘Pseudonymous works are by the author in his own person, except in the name he signs; heteronymous works are by the author outside his own person. They proceed from a full-fledged individual created by him, like the lines spoken by a character in a drama he might write. (p.xviii)’

Pessoa wrote to a relatively small reading public in the early decades of the twentieth century – in 1910 up to 70% of Portuguese adults were illiterate (when it was just 2 percent in England p.291) and his work hardly reached Brazil or other parts of the Portuguese-speaking world. He completed just one book – a visionary work of poetry infused with Romantic nationalism called Mensagem (Message) in 1934 – in his lifetime. Now Zenith’s extensive autobiography, masterfully capturing the historical context, brings global attention to an author whose ‘literary dispersion faithfully mirrors our ontological instability and the absence of intrinsic unity in the world we inhabit. (p.xxvi)’

From his earliest days, Pessoa produced a bewildering array of heteronyms – often as a form of play – amounting to well over seventy throughout his life. Some hardly assumed a life at all, including a personal favourite, the contradictory Friar Maurice: ‘a mystic without God, a Christian without a creed. (p.254)’

These became, according to Zenith, ‘ingenious vehicles for producing literature,’ and ‘also paths to self-knowledge. (p.119)’ The self-fragmentation seemed to come at a serious cost to Pessoa himself, however. Towards the end of his life he remarked: ‘Today I have no personality: I have divided all my humanness among the various authors whom I’ve served as literary executor. (p.41)’

From the outset, Pessoa’s poetry was identified with fingimento, a difficult word to translate, which can mean a kind of ‘feigning,’ ‘faking,’ ‘pretending ’ or forging (which has the double entendre of making and counterfeiting). This extended into an apparent unwillingness, or perhaps inability, to ever consummate a love affair, including his courtship of the forlorn Ofélia Queiroz, his only girlfriend; or to act on apparent homosexual urges – ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ – that pepper his work.

Throughout his life, according to Zenith there was ‘no clear lines of demarcation between’ the heteronyms, or ‘between fiction and reality. (p.146)’ Perhaps, unsurprisingly alcohol featured prominently – he died aged forty-seven after a life of excess – although contemporaries insist he always maintained an appearance of sobriety, perhaps his greatest pretence of all.

According to Zenith, Pessoa was ‘monosexual, androgynously so. The heteronyms can be seen as the fruit of his self-fertilization. (p.871)’ Thus, ‘daunted by the expectation of the world all around him’, he ‘preferred to inhabit the story of his heteronym. (p.192)’

Notably also: ‘Pessoa’s communicators, on at least a couple of occasions, gave him not merely poetic metaphors but actual poems. They were his impromptu muses, vivid manifestations from the spiritual realm where – he liked to think – his poetry and his heteronyms originated. (p.516)’

Alentejo, Portugal, 2019.

Alberto Caeiro

I have no philosophy, I have senses …

If I speak of Nature it’s not because I know what it is

But because I love it, and for that very reason,

Because those who love never know what they love

Or why they love, or what love is.

Alberto Caeiro from The Keeper of Sheep, 1914.

In later years Pessoa revealed that Alberto Caeiro began life as a joke figure of ‘a rather complicated bucolic poet’. He claimed he wrote ‘thirty-some poems at one go, in a kind of ecstasy I’m unable to describe. (p.379)’ But Pessoa – ever the feigner – was an unreliable witness. Zenith reveals that a thorough examination of his archive revealed ‘a rather different literary genesis. (p.379)’

Nonetheless, the invention of Caeiro in 1914 brought a creative release for Pessoa; liberating him from what Zenith describes as the ‘chrysalis formed by so much learning’ which had, until that point, inhibited him from coming ‘into his own as an astonishingly original poet’. Albeit this was a status ‘he would never have attained without the chrysalis. (p.159)’ He certainly fully understood the forms and rules of poetry, before breaking them.

Having spent ten years of his life, and schooling, in Durban, South Africa where he gained fluency in English, Pessoa had been vacillating between writing in Portuguese or English. Zenith maintains that Pessoa ‘did not know how to intensely feel in English; his poetic diction in this language was, oddly enough, too “poetical” (p.148)’, although he did produce a chap book of verse that was reviewed favourably in the London Review of Books no less.

One can imagine Pessoa in South Africa as a slightly effete adolescent surpassing his peers in academic learning, but whose accent always marked him as an outsider, a status which he unconsciously absorbed, and which generated a lifelong antipathy to the British Empire.

Caeiro therefore represented a form of homecoming – a statement of ‘Portugueseness’ – for a cosmopolitan young man struggling to form an identity. In this sense, Pessoa may be likened to W.B. Yeats, who also spent many years of his development in a country, which he ultimately rejected for an Irish mistress in Cathleen Ni Houlihan.

Caeiro, according to Zenith was also ‘a reaction against Fernando Pessoa – against all learning and incessant intellectual wrangling (p.386)’, thus the heteronym writes: ‘I lie down on the grass / And forget all I was taught.’

Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

Ricardo Reis

Let us also make our lives one day,

Consciously forgetting there’s night, Lydia,

Before and after

The little we endure.

Ricardo Reis, July, 1914

Richard Zenith observes of Ricardo Reis – the second of Pessoa’s three main heteronyms and fictional disciples of Alberto Caeiro – that he ‘espoused a revival of Greek moral, social, and aesthetic ideals, and the introduction of a new paganism, adapted to the contemporary mentality. (p.404)’

In part, Reis represents Pessoa’s view that ‘Religion is an emotional need of mankind (p.541)’, but also – having rejected doctrinaire Christianity, along with monarchy, in his youth – the imaginative possibilities of undogmatic polytheism, alongside a lifelong dedication to astrology and the occult.

Pessoa urged: ‘Let’s not leave out a single god! … Let’s be everything, in every way possible, for there can be no truth where something is lacking.’ Thus, according to Zenith, over the course of his life Pessoa, ‘groped like a blind man in maze of occult mysteries that, by definition, could never be fathomed. (p.541)’

The persona of Reis also represented a stoicism reconciled to the ‘slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’. Acceptance of fate, and the remote tragedies we encounter in news reports, is memorably conveyed in ‘The Chess Players’ (1916), where two protagonists play a game while around them a city is ransacked by an invading army. This is a kind of acceptance of events we generally cannot control that we might do well to learn from Ricardo Reis.

Notably, Ricardo Reis attained a literary afterlife in Portuguese Nobel laureate José Saramago’s 1984 novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, in which the heteronym returns to Lisbon from Brazil in 1935 to meet his death alongside Fernando Pessoa. A film based on the book was released in 2020.

Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

Álvaro de Campos

Faint vertigo of confused things in my soul!

Shattered furies, tender feelings like spools of thread children play with,

Avalanche of imagination over the eyes of my senses,

Tears, useless tears,

Light breezes of contradiction grazing my soul …

Álvaro de Campos ‘Maritime Ode’, 1915

The last and most important of Pessoa’s heteronyms, Álvaro Campos, was born, in Pessoa’s imagination at least, on Friedrich Nietzsche’s birthday. According to Zenith he represents ‘the Dionysian impulse – the intoxicating affirmation of life, felt in all its pains and pleasures. (p.397)’ In profound contrast to Pessoa, who regarded sex as dirty, Campos’s motto was to ‘To feel everything in every way possible. (p.521)’

The open-minded de Campos could be the liberated person Pessoa would never become: ‘Have fun with women if you like women’ he recommended, ‘have fun in another way, if you prefer another way. It’s all fine and good, since it pertains to the body of the one having fun … morality is the ignoble hypocrisy of envy” for “not being loved. (p.626)’

Yet the ghost of de Campos inhibited Pessoa, as ‘he’ attempted to get in the way of a relationship with the tragic Ofélia. ‘Today I’m not me, I’m my friend Álvaro de Campos, (p.589)’ he would warn his only meaningful girlfriend.

According to Zenith, Álvaro de Campos’s appetites in Freudian terms personified Pessoa’s id. Then perhaps the phlegmatic Ricardo Reis operated as ego, mediating the unrealistic id’s relationship to the world. These figures emerge under the tutelage of their acknowledged master, the Zen-like Alberto Caeiro – who was according to de Campos, ‘The Great Vaccine – the vaccine against the stupidity of the intelligent. (p.388)’

Thus, Caeiro can may be seen the superego, the ethical touchstone of a tripartite personality built around his universal Portuguese personality; similar to that constructed around the universal Russian character in Dostoyevsky’s Brother Karamazov that seemed to have informed Freud’s original understanding of these characteristics.

Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

The Book of Disquiet

Dead we’re born, dead we live, and already dead we enter death. Composed of cells living off their disintegration, we’re made of death.

The Book of Disquiet, Bernardo Soares

Fernando Pessoa described the main author of The Book of Disquiet, Bernardo Soares, as a semi-heteronym, or ‘mutilation (p.721)’ of his personality, and as such The Book of Disquiet served as a semi-factual autobiography. Of course, nothing is ever as it seems with Pessoa, so the character of Soares is an unremarkable bookkeeper who endeavours to avoid contact with the bustling world around him, while Pessoa himself was a relatively sociable bachelor.

Bernardo Soares he confided: ‘always appears when I am sleepy or drowsy, such that my qualities of inhibition and logical reasoning are suspended; his prose is an endless reverie. (p.870)’

In a sense, The Book of Disquiet is a book of the night, if not of quite of dream time, then of solitary down time and retreat. According to Zenith the book, which took years for scholars to reassemble from often scrawled notes, ‘never ceased being an experiment in how far a man can be psychologically and affectively self-sufficient, living only off his dreams and imagination. (p.364)’

It is a book of ideas and self-analysis. Thus, Soares reveals: ‘We never love anyone. What we love is the idea we have of someone. It’s our own concept – our own selves – that we love,’ and also, of self-reliance in solitude, where the intellect rises above material limitations.

It displays a belief in the magical quality of words. At one point he remarks – triggered by Walter Pater’s description of Mona Lisa’s smile containing: ‘the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of Borgias’ – ‘How much more beautiful the Mona Lisa would be if we couldn’t see it. (p.670)’

In his imagination Soares/Pessoa is ‘the naked stage where various actors act out various plays.’ Thus, The Book of Disquiet, according to Zenith ’magnificently illustrates the uncertainty principle that runs throughout his written universe. (p.xxiii)’

Also, in a time when we are urged to fulfil our potential, as a Capitalist economy demands constant self-improvement, the Book of Disquiet reconciles us to anonymity and the inner life of the imagination that we may rely on in times of adversity.

Alentejo, Portugal, 2019.

Political Commentator

The dazzling beauty of graft and corruption,

Delicious financial and diplomatic scandals,

Politically motivated assaults on the streets,

And every now and then the comet of a regicide

Lighting up with Awe and Fanfare the usual

Clear skies of everyday Civilisation!

Álvaro de Campos, ‘Triumphal Ode’, June, 1914,

Hired as a columnist for the newspaper O Jornal in 1925, Fernando Pessoa, writing as himself, proclaimed that ‘only superficial people have deep convictions.’ insisting that a modern intellectual ‘has the cerebral obligation to change opinion … several times in the same day.’ This person, presumably himself, might, for instance, be ‘a republican in the morning, and a royalist at dusk. (p p.450-51)’

Abiding by this injunction, Pessoa presented a dazzling array of viewpoints in the 1920s, having renounced Catholicism in his youth, and embraced republicanism prior to the Revolution of 1910. He also acquired a distaste for British imperialism while living in Durban, albeit not necessarily imperialism itself.

Pessoa was a roving provocateur, who, according to Zenith, ‘had a fondness for ardently defending a certain idea one day and then attacking it the next, with equally impassioned arguments. (p.340)’ Confrontationally, he opined in Nietzschean terms that the ‘plebeian class should be the instrument of the imperialists, the dominating class,’ and ‘linked to them through a community of national mysticism, such that it is voluntarily their slave. (p.453)’ The feigner’s tendency towards outlandish, objectionable views should be taken with a grain of salt, however, as the artist often played with literary tropes in political statements.

This applies to a frankly disturbing 1916 pronouncement that ‘Slavery is logical and legitimate; a Zulu or Landim [an indigenous Mozambican]represents nothing useful to the world. (p. p.533)’ Importantly, however, according to Zenith, who devotes considerable attention to the theme of race he never ‘publicly supported any racist ideology, (p.534)’ and in the 1920s remarked that ‘Mahatma Gandhi is the only truly great figure that exists in the world today, (p.78)’ while he was opposed to fascism from the beginning.

Until the 1930s Pessoa’s political views were in a chrysalis of café talk, untested by real authoritarianism, including censorship and a nascent police state under the dictator António Salazar.

Moreover, Pessoa was expressing his views during the chaotic first Portuguese Republic (1910-26), which experienced a series of political convulsions generating forty-four ministries and nine presidents, with frequent political assassinations. As Zenith puts it: ‘[t]he nation’s political centre, rather than being caught in a tug-of-war between ideological extremes, was caving in on itself. p.220)’

Pessoa was disgusted by the chaos, and rejected ‘the positivist project of certain republicans, who envisioned a science-based society of secular citizens illuminated by the twin virtues of order and progress. (p.424)’ ‘All radicalism fosters reaction,’ he warned, ‘since the informing spirit is the same. (p.312)’ In response, he developed his own reactionary idea an aristocratic republic. Progress, he argued, ‘could be achieved only through an aristocracy of superior individuals’ that, mercifully, have ‘nothing to do with blue blood or inherited privilege. (p.412)’

In 1928 he published The Interregnum: Defense and Justification of Military Dictatorship in Portugal where he argued that Portugal required a new political system but that this system had first to be discovered, and until then a military dictatorship was the best alternative. However, according to Zenith he ‘set himself apart from those who favoured a long-term authoritarian solution. (p.700)’

Only when put to the test would he display his true qualities, dismissing narrow appeals to national identity – proclaiming (as Bernando Soares) ‘My nation is the Portuguese language (p.791)’ – and defending individuals ‘whom he regarded as the true creators and only deserving beneficiaries of civilization. (p.742)’

Alentejo, Portugal, 2019.

Under Salazar

Ah, what a pleasure

To leave a task undone,

To have a book to read

And not event crack it!

Reading is a bore,

And studying isn’t anything.

Fernando Pessoa-Himself ‘FREEDOM’, 1935

According to Zenith, Pessoa ‘smelled a rat in Mussolini (p.640).’ The Italian dictator had become a popular figure among the Portuguese intelligentsia of the period in search of a solution to the country’s catastrophic instability.

Zenith writes: ‘Pessoa continually oscillated between a Promethean impulse to help humanity, to be involved in the world, and a contrary inclination to retreat and seek perfection in the artistic space of a poem. (p.217)’ Confronting dictatorships across Europe in the 1930s he ceased feigning and honoured that Promethean impulse, at a significant cost to his career.

Pessoa opined, in the heteronym of Thomas Crosse, that Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin and Salazar were all ‘unbalanced characters,’ whose ‘limited vision of reality’ might, he acknowledged, make them effective but they shared the same ‘hatred of intelligence, because intelligence discusses.’ They were all, therefore, ‘enemies of liberty’, which if ‘not individual, is nothing,’ and saliently observed that, by nature, dictators ‘are unhumorous, because a sense of humour preserves a man from that maniac confidence in himself by which he promotes himself dictator (p.841).’

The priest-like – another lifelong bachelor – Salazar may have been a less monstrous character than other dictators of that era, but his “interregnum” would last almost fifty, stultifying years. A trained economist, who summarily banned gambling halls in Lisbon on taking power, before introducing austerity measures that appear suspiciously similar to those inflicted during our neoliberal era. A motto of ‘faith, moral guidance, and the spirit of sacrifice (p.705)’ is also reminiscent of public health exhortations under lockdown.

According to Zenith, Pessoa ‘instinctively bristled when he was expected to be a willing and even joyous participant in a mass movement, whatever it was. (p.293)’ Unsurprisingly, he reacted against propaganda projecting a ‘myth of a peaceful, bucolic Portugal where peasants joyfully hoed corn, tended cattle, picked grapes and wove baskets, while singing traditional songs and dancing in their spare time. (p.892)’

As a writer he was also infuriated by Salazar’s demand that literary works should observe ‘certain limitations,’ and embrace ‘certain guidelines’ defined by the New State’s ‘moral and patriotic principle.’ Salazar said that writers should be ‘creators of civic and moral energies’ rather than ‘nostalgic dreamers of despondency and decadence. (p.880)’ This remark seemed to have been aimed at Pessoa himself.

In response, he caustically observed that the word Salazar was made up of sal (salt) and azar (bad luck), and that rain had long ago dissolved the sal, leaving Portugal with nothing but azar (p.883). He would also write a sarcastic poem wishing that for once the radio announcer would tell listeners ‘what Salazar did not say (p.891).’

By the time of his death in 1935 Pessoa had come around ‘full circle’ according to Zenith ‘returning to the high-minded and large-hearted ambitions of his youth (p.903)’, arguing democratically that the nation is ‘worth the sum of its individuals (p.914).’

In response to Mussolini’s invasion of Abyssinia in 1936, Pessoa would ask: ‘what are we all in the world if not Abyssinians?’ Between us and them he saw a ‘vast and broad human fraternity (p.915)’

In response to the censorship of an article he wrote condemning Mussolini’s invasion, as well as discrimination against openly gay poets such as António Botto and the banning of the Freemasons and other secret societies, he took the dramatic decision to quit publishing in Portugal. In return for this he received an unwelcome visit from Salazar’s secret police, although he was largely left to his own devices until his death aged just forty-seven.

Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

In History

No, I don’t want anything.

I already said I don’t want anything

Don’t come to me with conclusions!

Death is the only conclusion.

Don’t offer me aesthetics!

Don’t talk to me of morals!

Take metaphysics away from here!

Don’t try to sell me complete systems, don’t bore me with breakthroughs

Of science (of science, my God, of science!)–

Of science, of the arts, of modern civilization!

Álvaro de Campos ‘Lisbon Revisited’ (1923)

What to make of an artist such as Fernando Pessoa almost a century on from his death?

First, huge credit goes to his biographer Richard Zenith, who has assiduously assembled the parts of an extraordinarily complex life. Readers may feel daunted by such a weighty tome, but this represents a bible for English speakers, at least, conjuring a literary titan, deserving our attention alongside Shakespeare, and few others, such is his contribution to world literature.

Once suspects that Zenith himself must have struggled to maintain a coherent sense of self in the face of such a fecund imagination as Fernando Pessoa’s.

In the characters of the three heteronyms, the semi-heteronym and Pessoa as himself we find spiritual resources that may guide us – like Virgil in Dante’s Divine Comedy – through the labyrinth of an increasingly mediated age of increasing homogenisation and fake authenticity in the arts. And, like Virgil perhaps, he takes us to the gates of heaven, and no further.

With Alberto Caeiro – the vaccine against the stupidity of the intelligent – we may see nature in its glorious parts, at a remove from crippling intellectual conceits. Or we may dance with Ricardo Reis, maintaining order and composure in the face of chaos and deceit. That arch-sensualist, Álvaro de Campos, meanwhile, demands we appreciate all aspects of our journey through life, while taking aim at hypocrisy when required.

Then Bernardo Soares should be appreciated for his self-sufficiency and celebration of the interior world of the mind. Lastly, Fernando Pessoa as himself represents a narrative arc, wherein a true love of humanity, and human wellbeing, eventually asserts itself in the face of tyranny.

All these voices, and more, are what make Fernando Pessoa an essential poet for age.

Poetry translated by Richard Zenith, Fernando Pessoa, A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe, Penguin Classics, London, 2006.

With thanks to Bartholomew Ryan for editorial assistance.

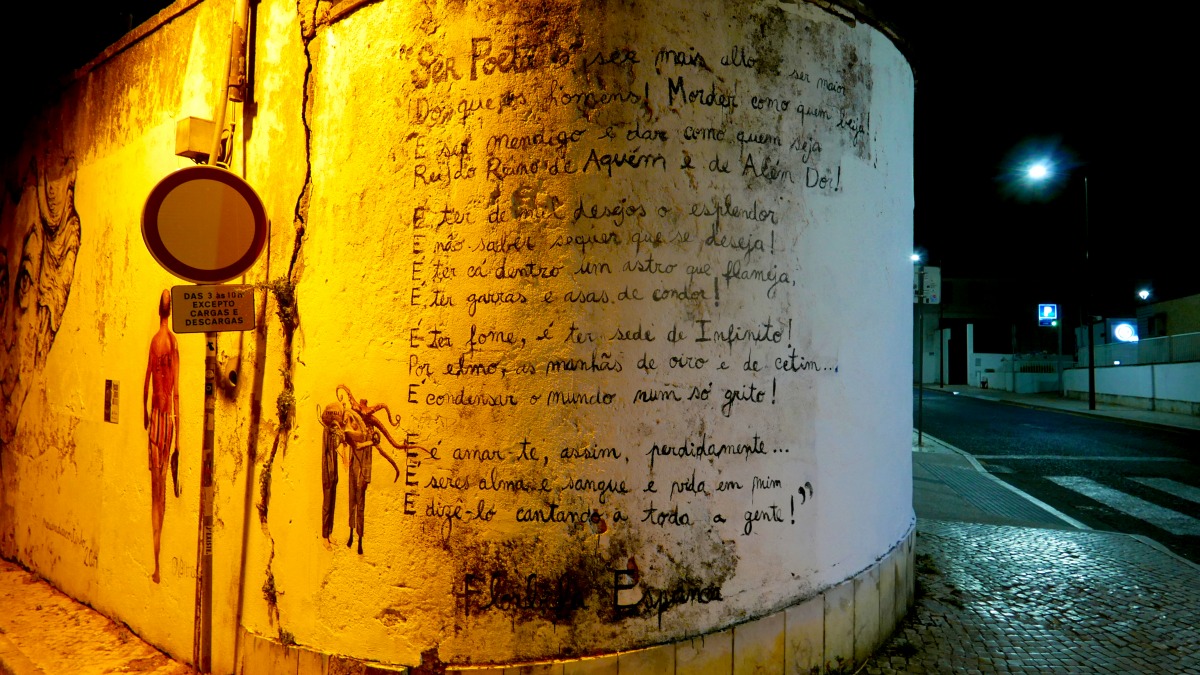

Featured Image: Image of Ser Poeta by Florbela Espanca in Lisbon, Portugal (2019).