Through Fernando Pessoa the flesh was made word. Reminiscent of the renowned Chinese painter Wu Daozi, who, as legend has it, vanished into one of his own landscape paintings, Pessoa (1888-1935), the great Portuguese poet, appears to have disappeared bodily into his written works. Dispersing himself into the many lives of others through the medium of writing, Pessoa became nobody and many others simultaneously.

Pessoa called these many others ‘heteronyms’ (other names). These distinct others who discovered a voice through Pessoa have left behind a treasure trove of philosophically charged poetic works. Their wide-ranging and diverse works created by the ‘secret orchestra’ of Pessoa’s soul have given rise to a choral symphony whose resonance intensifies over time.

One is left in a state of silent wonder and awe at the sheer scale and brilliance of what Pessoa managed to achieve while semantically composing the soul. The challenge for his readers is to break this silence and put into words what it is that Pessoa accomplished, thereby naming precisely his significance for how we humans understand ourselves, the way we see things, and how we dwell upon the earth.

Astute Philosophical Experimentation

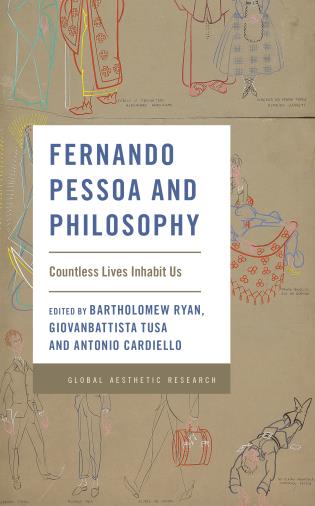

A new book, Fernando Pessoa and Philosophy: Countless Lives Inhabit Us edited by Bartholomew Ryan, Giovanbattista Tusa, and Antonio Cardiello (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Maryland, U.S, 2021) takes on this challenge with gusto.

Its aim is to bring to light Pessoa’s in-depth knowledge of philosophy and his ability to engage in astute philosophical experimentation, and at the same time highlight his capacity to confront, appropriate, synthesise, and strip bare complex ideas into art. Additionally, by focusing on Pessoa’s writings through different philosophical lenses the chapters included in this volume seek to reveal novel ways of interpreting some of the seminal problems of philosophy.

Bartholomew Ryan alerts us to the relevance and urgency of this task in his Introduction, where he claims that if ‘philosophy is to survive the various crises of human civilization ahead of us, to respond and open up new pathways of thought’ we will need the assistance of ‘experimenters in literature, in order to help us reconnect with ourselves, others and all living species on the planet.’

Structurally, Fernando Pessoa and Philosophy consists of an Introduction, Exordium, Notes for the Memory of My Master Caeiro, fifteen essays dedicated to Pessoa and philosophy, a detailed appendix, and a critical bibliography. The wide range of elements that make up this volume come together to create a joyous banquet of a book.

Ryan opens this feast for the soul with a fast tempo-ed, polyphonous introduction, entitled ‘An Encounter between the Poet and the Philosopher’. He notes how it is the task of the philosopher not to read a poet in order to appropriate an idea for her/his own purposes. Instead, the philosopher is prompted to engage with literature so as to learn how to dwell in an uncomfortable and uncontrollable region.

For in this strange region where philosophy and poetry meet something innovative can occur. As Ryan writes: ‘It is in this encounter between the philosopher and poet a vulnerability is opened on both sides to inspire the creating of a new concept in the philosopher and a new form and linguistic gesture in the poet.’

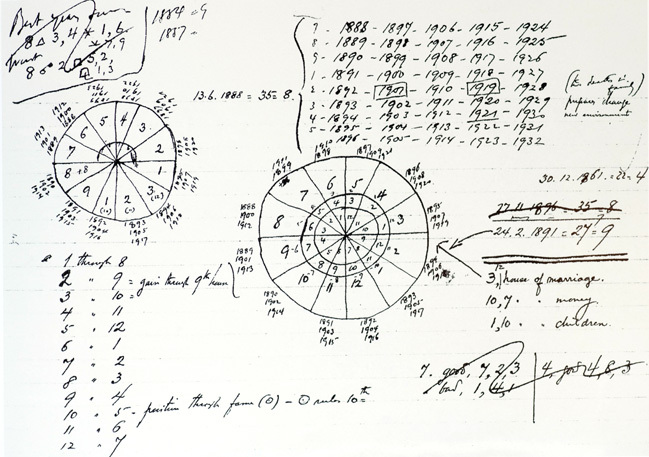

One of Pessoa’s astrological charts from 1916.

A Sense of Journey

By entering into such an encounter with Pessoa, the philosopher has a lot to explore and discover. As a poet animated by philosophy Pessoa prioritises a sense of journey over notions of progress, development and evolution, as he writes: ‘I don’t evolve, I JOURNEY’.

Besides his emphasis on journeying, the heteronym Álvaro de Campos shares a similar vision for both the philosopher and artist when he notes in his futurist manifesto ‘Ultimatum’, how the philosopher should contain ‘the greatest number of other people’s personal philosophies; and that the artist should write ‘in the most genres with the most contradictions and discrepancies.’ These insights offer rich food for thought for the philosopher.

The Exordium and Notes for the Memory of my Master Caeiro come after the Introduction. These two marvellous sections are comprised of words from Pessoa and four of his heteronyms, namely, Alexander Search, Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis. They serve to attune and acclimatise the reader to the mood and atmosphere of Pessoa’s writings.

Some sentences shine luminously in the Exordium, for example, ‘There is for me – there was – a wealth of meaning in a thing so ridiculous as a door-key, a nail on a wall, a cat’s whiskers. There is to me a fulness of spiritual suggestion in a fowl with its chickens strutting across the road.’

Notably, the Exordium and Campos’s Notes also reveal the humour and irony of Pessoa’s writings. Campos writes in his Notes of the fictitious nature of the orthonym Fernando Pessoa: ‘Even more curious is the case of Fernando Pessoa, who doesn’t exist, strictly speaking.’

And when humorously critiquing the work of the great 19th century writer Giacomo Leopardi, Pessoa claims Leopardi’s philosophical pessimism and overemphasis on suffering stems from a shyness with women. Pessoa remarks: ‘“I am shy with women: therefore there is no God” is highly unconvincing as metaphysics.’

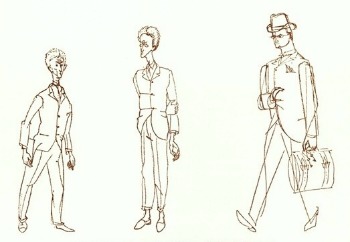

Ricardo Reis, Alberto Caeiro and Álvaro de Campos seen by José de Almada Negreiros.

Four Sections

Fernando Pessoa and Philosophy is then divided into four sections: Spiritual Traditions, Metaphysics and Post-metaphysics, Philosophies of Selfhood, and Contemporary Problems and Perspectives. Each section has three to four chapters. The volume has been arranged by philosophical themes which are both central to Pessoa’s work and to philosophy itself. The first section, Spiritual Traditions, focuses on Neopaganism, Daoism, Indian, and Islamic philosophy.

The first chapter by Antonio Cardiello, ‘Fernando Pessoa’s vision of Neopaganism as Life’s Supreme Art’ explores Pessoa’s project of reawakening polytheism and the Hellenic model of civilisation. Cardiello observes how Pessoa, using his orthonym, calls for a ‘superior paganism’ for modern times in which ‘all protestantisms, all Oriental credos, all paganisms, dead and alive become Portuguesely fused.’

In addition to a ‘superior paganism’ Pessoa makes reference to a ‘superior art’ that can ‘lift the soul above everything narrow, above all instincts, moral or immoral concerns.’, and liberate us from ‘life itself.’ Merging a superior paganism with a superior art, Cardiello claims it was Pessoa’s task to denounce two millennial of moral interpretation and substitute it for an aesthetic one that glorifies human life, thereby dispensing with unhealthy values for healthier ones that encourage humans to flourish.

Paulo Borges’s ‘Fernando Pessoa, Daoism and the Gap: Thought of Insubstantiality, Vagueness and Indetermination’ is the second chapter in this section. It closely examines emptiness and the ‘gap’ in the writings of the orthonym Fernando Pessoa and the semi-heteronym Bernardo Soares, comparing these themes with Daoist principles.

According to Daoist thought, emptiness allows the emergence of the ‘ten thousand beings’ or the infinity of possibilities and the possibility of an authentic life lacking self-centredness. Borges highlights how in Pessoa, the overabundance of becoming other and the experience of heteronymy emerges from that insubstantial emptiness of self and of everything.

While the abyss of being prior to defining oneself by naming oneself, surfaces as the ‘gap’ that ‘is between’ the self and itself. Towards the conclusion he identifies a wonderfully apt quote from Tchouang Tseu to describe Pessoa. Tseu writes that ‘the perfect man is without any I, the inspired man is without work; the holy man leaves no name.’

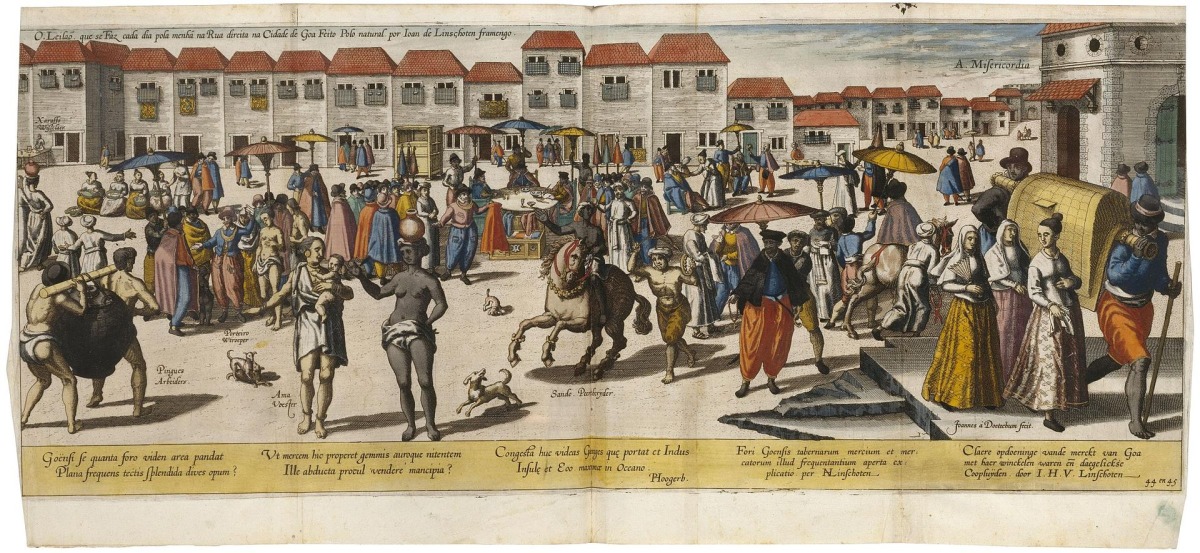

Marketplace in Goa, as depicted in Jan Huygen van Linschotens Itinerarium.

Imaginary India

The third chapter, ‘Pessoa’s Imaginary India’, by Jonardon Ganeri, looks at Pessoa’s understanding of the ‘Indian ideal’ which he interprets as signifying the transcendence of the illusion that is living a human life.

Pessoa regards the Indian ideal as ‘inhuman’ and speaks of ‘the principle, which we already know to be absurd, that the universe is an illusion.’

Ironically, Hindu thinkers writing at the same time as Pessoa, such as Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan share Pessoa’s critical sentiments towards this ideal. Borrowing a phrase from Nietzsche, Ganeri acknowledges an ‘ironic affinty’ between Pessoa’s position that he occasionally assumes as his own contraposition to the ‘Indian ideal’, and the ideas of his contemporaries in India that he never knew.

In the final chapter of this section, ‘Pessoa and Islamic Philosophy’, Fabrizio Boscaglia, brings to light Pessoa’s engagement with Islamic philosophy and its impact on his writing. Boscaglia draws attention to Pessoa’s interest in the philosophical thought of Omar Khayyām, through Edward Fitzgerald’s translations, and the possible connections of Sufism in Pessoa’s poetry.

Boscaglia also demonstrates how Pessoa’s makes several references to the Islamic civilization as the keeper, interpreter and transmitter of Greek culture between the Middle Ages and the Renaissnance.

In the second section of this book, Metaphysics and Post-metaphysics, the topics of time, nihilism and the nothing, transcendentalism, immanence and becoming-landscape take centre stage. João Constâncio opens the section with ‘Nihilism and Being Nothing in “The Tobacco Shop”’.

The chapter seeks to respond to two significant questions: 1. What is the meaning for Pessoa, particularly in the masterpiece ‘The Tobacco Shop’ (by Álvaro de Campos) of ‘being nothing’ and 2. How can the study of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche’s philosophical writings contribute to the understanding of such a paradoxical way of being, which consists of ‘being nothing’?

Constâncio delves into Campos’s despair for ‘being-nothing’ and reveals it to be tantamount to despairing for having to be a mask, for not being able to avoid adopting an identity that is a mere linguistic construction, regardless of whether it implies some ultimate metaphysical purpose implicit to life within society.

Furthermore, Constâncio shows how Campos’s ‘conscious consciousness’ makes him envy those who, living by way of an ‘unconscious conscious’, manage to believe in an identity that is intersubjectively attributed to them.

‘Pessoa and Time’ by Pedro Duarte is the second chapter in this section. For Duarte, it is possible to grasp the individuality of each of the three heteronyms Caeiro, Reis and Campo, by studying their different approaches and responses to time.

But Duarte also includes Pessoa, the orthonym, in his analysis. For Pessoa the past needs to be rediscovered, and not set aside, because it summons the present to build the future. Caeiro takes time out of things, through detachment and unlearning and to see without thinking. Caeiro writes ‘I don’t want to think of things as being in the present; I want to think of them as things’.

Reis believed that ‘we pass like the river’ through life. For Reis, existence was all about adhering to this passage. Aging should be accepted. On the other hand, Campos desires to feel everything in every way, and find the beauty of the present moment, a beauty unknown to the ancients, hence electric lamps and factories are to be celebrated. Campos says ‘I who love modern civilization and kiss machines with all my soul.’

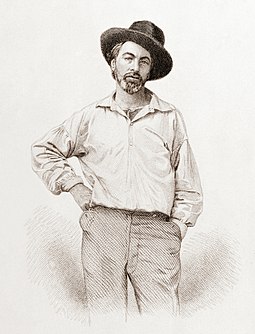

Walt Whitman aged 35.

American Transcendentalism

Benedetta Zavatta’s chapter entitled ‘Pessoa and American Transcendentalism’, investigates the link between Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman and Pessoa. Emerson’s influence on Pessoa had not received scholarly attention prior to Zavatta’s essay.

Zavatta convincingly hypothesises that Pessoa was drawn to Emerson and Whitman by the notion, repeatedly articulated by these two authors, that every individual latently contains within herself/himself the seeds of an infinite number of different personalities.

This in turn enables an individual to foster an empathetic connection with other humans, to the point where they ‘become them’. Enlarging this empathetic connection allows one experience how the whole world is seen and felt as these others see it and feel it.

In the chapter ‘Bernardo Soares’s Becoming-Landscape’, José Gil explores the use of landscape in The Book of Disquiet. Gil’s philosophical approach to The Book of Disquiet opens up this impossible book for the reader, by revealing that each of its fragments is ‘a veritable landscape-state of emotion’, providing it with ‘both skeleton and flow’.

Gil’s deft analysis of Bernardo Soares’s becoming-landscape culminates with an enquiry into what occurs when the plane of the landscape clashes with the plane of emotions. Gil suggests ‘all distances disappear, and the “I” itself, which functioned like a screen between sensations and the landscapes, explodes, disappears and ceases to exist’.

What remains is the pure landscape of event-sensations. A ‘sensation-universe’. Literary description ceases, and ‘sensations attach themselves to the flow of the landscape because they result from them: it is no longer the sky yonder, or the I, here, like this sky: it is the sensation-sky or the sensation-light.’

'the forests were monstrous / but they have always been divine' We bring you the lyrics and a first recording of Iguatu from Bartholomew Ryan of the Loafing Heroes to mark Earth Day 2020.#EarthDay2020 #EarthDay https://t.co/wDjSA07dwm@broadsheet_ie #theloafingheroes

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) April 22, 2020

Philosophies of Selfhood

The third section, Philosophies of Selfhood, examines the dissolution and plurality of the self and subject in Pessoa’s writings. It commences with Bartholomew Ryan’s chapter ‘Voicing Vacillation, Logos and Masks of the Self: Mirroring Kierkegaard and Pessoa’.

Ryan argues that, in the journey of forging the human self or subject into writing, the achievements of the poet Pessoa and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard remain unsurpassed. Through Pessoa and Kierkegaard, Ryan investigates the making and unmaking the elusive self through vacillation, logos and masks.

At the core of this study lies doubt, which Ryan claims both writers see as the sickness and heartbeat of modernity. Pessoa and Kierkegaard voice doubt and despair, as the poetic-philosopher and philosophical poet.

According to Ryan, Pessoa delights in aesthetic melancholy and being allied to no one or no thing except literature. Describing Pessoa as an Argonaut of Modernity or the Argonaut of true sensations, Ryan envisages him journeying ‘to the abstract chasm that lies at the depths of things’ and questioning the philosophical problems of selfhood by voicing its vacillation, logos and masks. Buffeted by this tormenting journey, Pessoa vacillates between knowledge and faith, and experiencing the elusive moment.

In ‘The Difference between Othering Oneself and Becoming What One is’, Maria Filomena Molder states that the dictum of ‘becoming what you are’ is nowhere to be found in Pessoa, and the concept of ‘othering oneself’ belongs in other waters.

Drawing support from Nietzsche’s insight in Twilight of the Idols that the ‘I’ has become a fairytale, a fiction, a play on words’, Molder proposes that Pessoa has no need for a theory of the subject. Molder then shows how Pessoa coined the term ‘othering oneself’ in order to account for the multiplicity of writers who are born out of his way of writing.

According to Molder, othering oneself, ‘proceeds not from the plurality of the subject but from a precocious, childlike inclination to imagining oneself as multiple characters, a succession of dramatic scenes secreted by creative play.’

This incisive and succinct chapter draws to a close with the claim that Pessoa and his heteronyms are not liberators. What is he, then? Molder asks, and answers through the mouthpieces of Ricardo Reis and Pessoa.

The answer from Reis is: ‘I am merely the place/Where things are thought or felt’. And Pessoa responds: ‘I look at them. None is me, but I am their ensemble’. Not done yet, Molder asks: What does Pessoa want? And this time Pessoa replies: ‘I want to be the creator of myths, which is the highest mystery achievable by a member of the human race.’ And so Molder reveals the undecipherable mystery of the many in one, of the one in the many.

We revisit David Langwallner's wide-ranging discussion of the work of the French philosopher who anticipated many contemporary trends, now with a new preface and podcast in the wake of the pandemic. https://t.co/2LPyllOoHG@broadsheet_ie #panopticon #michelfoucault @DLangwallner

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 16, 2020

Foucault

Gianfranco Ferraro’s chapter ‘A Hermeneutics of Disquiet: Approaching Pessoa through Foucault’ concludes is final one in this third section. Ferraro tends to Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet through the ‘toolbox’ provided by Michel Foucault’s in The Hermeneutics of the Subject.

Why Foucault? For Ferraro, Foucault’s terminology, specifically in relation to ‘technologies of the self’, greatly assist us in interpreting Pessoa. These technologies highlight, in Ferraro’s own words, ‘practices which permit individuals to effect by their own means, or with the help of others, a certain number of operations on their own bodies and souls, thoughts, conduct, and way of being,’ so as to ‘transform themselves in order to attain a certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, perfection, or immortality’.

Consequently, approaching The Book of Disquiet through Foucault’s hermeneutics of the self allows us to see how Pessoa recovered many of the ancient practices and technologies of writing and how modernity adopted them again.

Borrowing from Foucault’s hermeneutic toolbox Ferraro reaches the conclusion that we can observe in The Book of Disquiet a work that summons one to oneself and to experimentation of oneself in revealing the many beings that lie dormant in our forms of life.

"lacking Yeats’s ‘grand ambitions and conviction, Fernando Pessoa was more like a jazzman of higher, occult truth, improvising on standard doctrines of the esoteric repertoire and introducing his own variations, without staying in any one place for long."https://t.co/mMvVZAmM5F

— Frank Armstrong (@frankarmstrong2) October 22, 2021

Contemporary Problems and Perspectives

The fourth and final section Contemporary Problems and Perspectives concentrates on value theory and secular capitalist modernity; the logic of seeing, ecological thought, and the fundamental relationship between poetry and some contemporary philosophers.

‘Pessoa’s “The Anarchist Banker” and the Logic of Value’, by J.D. Mininger offers a thorough reading of Pessoa’s short story ‘The Anarchist Banker’, which in part is supplemented by Nietzsche’s essay ‘On Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense’.

Anarchism strives to vanquish all social conventions and fictions, and is thus in a sense morally and politically motivated. Yet it could also be understood as signifying the freedom from such conventions and fictions.

In this story the anarchist achieves his own freedom by becoming a banker. According to Mininger, the essential politics of this story does not lie in the author’s construal of anarchism, but in the silent relation between philosophy and literature, between algebra and story, between proposition and performance, between constraint and freedom.

For Mininger, Pessoa’s story is an anarchistic act to the extent that it expresses freedom through constraint – a paradox made possible by the literary surplus value that is both the story’s cause and effect.

The second chapter in this section ‘For Your Eyes Only: The Logic of Seeing in Alberto Caeiro’s Poetry’, by Bruno Béu, opens with the words of the artist Kazmir Malevich, ‘I have transformed myself in the zero of form’ found on a leaflet distributed at the exhibition Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings 0.10 (zero-ten).

One of Malevich’s most famous works is his 1918 painting entitled White on White, showing a white square against a white background. As a work of art it calls into question the very possibility of form and representation.

Bèu in this chapter draws connections between Malevich’s paintings, and Caeiro’s poetry, in which language is being forced to reach its zero ability to signify things, while our experience of things is ‘freed’ from any re-presentation that we make of them.

Bèu demonstrates how Caeiro’s tautological discursive and logical performance is a radical negation of all possible predicates. This linguistic process leaves each thing absolute, indescribable and indefinable. As Bèu poignantly remarks ‘It is as if, through this process, each thing revealed itself and spoke from the top of Mount Sinai pronouncing the tautological and biblical words: ‘I am that I am’.’ As such no-thing is said for things to be seen, and ‘Poetry turns white on white’.

Image (c) Daniele Idini.

Ecological Dimensions

In the chapter ‘Where Does Fernando Pessoa Dwell? The Economy and Ecology of the Heteronyms’, Michael Marder illuminates some of the ecological dimensions to Pessoa’s work. This is attained through an analysis of what Pessoa called ‘disquiet’, to outline what Marder names a new ‘economy and ecology of the heteronyms’.

‘Disquiet’, in the sense of being unsettled, describes the possibility that dwelling and the dweller no longer exist, or, perhaps, never have.

For Marder, Pessoa is the place where dwelling might be reimagined, or, the placeholder for the lives of others. Turning his focus to Caeiro, Marder asserts that he wants to dwell in a world unspoiled by the ideal and idealising system of co-ordinates.

For Marder, Caeiro’s poetic project is to liberate the ‘innocent’ green and flourishing earth from the imaginary lines that have divided its surface through social and political conventions.

‘So where does Pessoa dwell?’ Marder asks at the close of this chapter. Marder’s response: ‘Between economy and ecology, between nowhere and everywhere’. Pessoa’s heteronyms outline an ‘economology’, where dwelling and unsettlement are not formally opposed to one another, a place where it is possible to dwell in the very unsettlement that acknowledges the impossibility of dwelling.

Giovanbattista Tusa’s ‘The “Pessoa Event”: Notes on Philosophy and Poetry’ concludes this section. Tusa’s text articulates the fundamental relationship between poetry and philosophy through Fernando Pessoa and the works of Martin Heidegger, Jacques Derrida, Alain Badiou and Jean-Luc Nancy.

Badiou in particular takes on a hugely significant role in this chapter, for it is he who notes that the poem far from being a form of knowledge, is the instance of thought subtracted from everything that sustains the faculty of knowledge.

Tusa also cites Badiou’s Handbook of Inaesthetics in which he claims to be contemporaries of Pessoa is ‘a philosophical task’, and through the reading of his work, philosophy could experience its own incapacity or perhaps its own impossibility.

After these four sections, Jerónimo Pizarro provides an appendix to the book called ‘Pessoa and Philosophy: Texts from the Archives’. This is a collection of selected Pessoa texts alongside images from the Pessoa archive referencing philosophy and various philosophers.

Pizarro’s fine scholarly research gathers editions and studies on a series of documents from Pessoa’s archive to help with future comparative research. The volume ends with a critical bibliography of Pessoa’s own works published in English, books on philosophy that he owned and secondary works on Pessoa and philosophy.

Fernando Pessoa and Philosophy sheds a remarkably illuminating spotlight on the wonderous writings of Pessoa, but most importantly it instils in the reader a sense that sections of his ‘secret orchestra’ have yet to be heard, and that future exploratory journeys await.

Feature Image: José de Almada Negreiros, Retrato de Fernando Pessoa.