The colourful humourist and English poet laureate, Sir John Betjeman (1906-1984) is the subject of Dominic Moseley’s Betjeman in Ireland (Somerville Press, 2023), which is lavishly illustrated with photographs.

Betjeman, who took his teddy bear, Alfie with him to Oxford in 1925 was the inspiration for the character of Sebastian Flyte in Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Posted to Dublin as press attaché in the British Embassy during World War II from early 1941 to autumn 1943, his love affair with Ireland had begun two decades earlier in Oxford. There he met, and had a unique affinity with, the remnants of the Irish Ascendancy in all their fading glory. Chief among them was Edward Pakenham, 6th Earl of Longford who lived in what is now, Tullynally Castle in Co. Westmeath. It was Pakenham who first brought Betjeman to Ireland in 1925.

An unapologetic social climber, Betjeman was the son of a furniture manufacturer from North London. Yet he was often ridiculed for his remorseless snobbery and his upwardly mobile pursuits. He finally enrolled in Magdalen College, Oxford after some difficulty in 1925, and it was in Oxford he met influential people such as C.S. Lewis and Maurice Bowra and Evelyn Waugh but also members of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy who held a unique charm for him and with whom he formed a special bond. Indeed, his road to social success seems to have been through the back door of the Irish Ascendancy.

Betjeman nourished an abiding fascination with Ireland from his Oxford days, especially the Irish Aristocracy – the more eccentric the better. He declared his ‘particular’ fondness for ‘people who had gone to seed’.

Others in the roll call of Betjeman’s Irish friends were Lord Rosse of Birr Castle, Basil Ava of Clandeboy House, Co Down Northern Ireland. His life-long love affair with Ireland was cemented in 1951 when, aged forty-six, he met the twenty-year-old Elizabeth Cavendish of Lismore Castle, who became his lifelong mistress and muse, causing occasional, great misery to his aristocratic wife Penelope.

It was through such aristocrats that Betjeman got his first taste of Ireland and when he arrived in Dublin as press attaché in 1941, whereupon he immersed himself further into that circle. Described affectionately by Moseley as ‘an ambitious social alpinist’ who ‘dearly loved a lord and lady’ he shamelessly cultivated them. Indeed, his enthusiasm for the Irish upper crust bordered on sycophantic.

Moseley chronicles an awesome litany of love affairs, flirtations and dalliances indulged in by Betjeman. But this larger than life, affable, and energetic figure could still say, incredibly, in later life that the one regret he had was not ‘having had more sex.’

It was possibly because of Betjeman’s popularity among Ireland’s Ascendancy he was chosen as press attaché. He soon became an instant hit among the literati of the Palace Bar, on Fleet Street in Dublin. This helped fulfil his mission ‘to ameliorate the anti-Irish tone of British press and to dilute the anti-English sentiments of the Irish press.’

In the Palace Bar the influential editor of the Irish Times, RM Smyllie ‘held court’ among a wide audience. Betjeman charmed a formidable array of artists and writers such as Sean O’Faolain, Frank O’Connor, Brinsley MacNamara, Flann O’Brien, Patrick Kavanagh, Austin Clarke, Terence de Vere White, Maurice Craig, Cyril Cusack and numerous others from the world of literature who also wielded a lot of influence.

He was no less popular among the artists he befriended such as, Paul Henry, Jack B. Yeats, Harry Kernoff, Sean O’Sullivan and numerous others. This group was ‘the locus of soft power’ in Ireland and once Betjeman was accepted and esteemed in this circle his success in Ireland was assured.

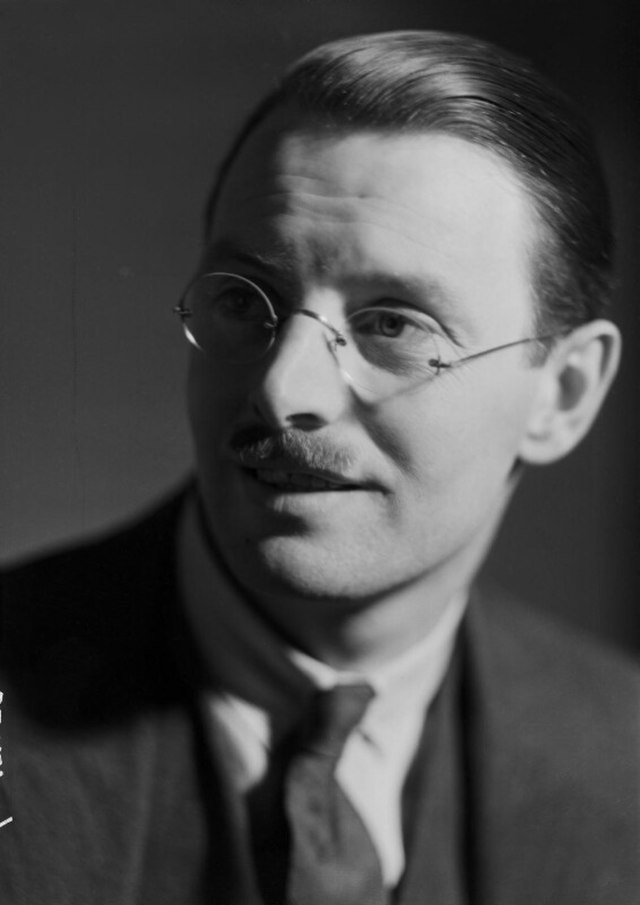

Portrait of Seán Ó Faoláin by Howard Coster, 1930’s

Ireland could easily have become a strong ally for Germany against Britain. Betjeman had ‘stepped into a historical minefield with little resources except his natural affability’. He certainly seems to have had a major diplomatic impact, and his friendship with the writer, Elizabeth Bowen – herself working for the British Ministry of Information and an on-off lover of Sean O’Faolain – was sure to have helped Betjeman.

It was Betjeman’s easy charm, wit and affability that made him a huge success in Ireland and his encounters with the Irish politicians of the day, including Éamon de Valera were very successful too: he had a sympathy with the problems posed by partition in the North, but this did not prevent the IRA classifying him, for a time, as a person of ‘menace’, although the plot to assassinated him was later dropped.

In 1942, he used his influence to get the English Horizon literary and artistic magazine to do an Irish number, featuring among others, Sean O’Faolain, Frank O’Connor, Patrick Kavanagh and Jack B Yeats.

What this entertaining page turner underscores is that John Betjeman was first and foremost a gifted poet who ‘celebrated every aspect of the idea of love’ and was especially ‘a poet of place whether it be the home counties, Oxford, Ireland or his beloved Cornwall.’

Unsurprisingly, he had a particular affinity with, and admiration for, Patrick Kavanagh where a sense of place is always foremost in the latter’s poems.

A major early influence was Goldsmith’s ‘Deserted Village.’ Betjeman’s passion for place, for architecture, for locations, for churches and old ruins saturates his poems and this is very much the case regarding his most celebrated Irish poem ‘Ireland With Emily’ where place fuses with his unrequited passion for Emily Hemphill of Tulira Castle in Galway (later to become Emily Villiers-Stuart of Dromana House, Waterford). It is one of his finest and most evocative poems about Ireland.

Betjeman’s passion for architecture flourished in Ireland too and his love of stately houses often outstripped his passion for their occupants, albeit he later wondered ‘how many linen sheets in the houses of Ireland received his lustful limbs.’ The combination of place with the erotic in his poems is described as a ‘potent brew’.

He waxed erotically about Furness House, Kildare, Shelton Abbey, Wicklow, Woodbrook House, Portarlington, Pakenham Hall, Westmeath and numerous others. Betjeman even learned the Irish language and frequently signed himself Sean O’Betjemán. His heart-rending Irish poem ‘A Lament for Moira McCavendish’ is another fine example of how place and love conflates in a way unique to Betjeman.

He might, as the author suggest, ‘have by his association with Elizabeth Cavendish, ascended to the highest rung’ socially but the portrait that emerges in this book is of a complex, flawed but likeable, warm human being with a large-hearted humanity and a unique generosity of spirit. It was that quality that made him the perfect diplomat in Ireland at the time.

A devout Anglican who feared the afterlife he emerges as the most loveable of ‘sinners’ in this book. His ‘Ballad of the Small Town in Ireland’ is likened to a Thomas Moore melody in which he celebrates the ordinary life of fair days, burned barracks, elegant squares, neglected graves, ruined churches and court houses.

Above all, Betjeman’s pre-eminence as a poet of merit is vigorously reclaimed in this study. The author notes how the ‘Modernism’ in poetry championed by T.S. Eliot and E.E. Cummings paved the way for an, often ‘graceless poetry devoid of scansion, rhyme, metre and original thought’.

As a traditionalist Betjeman is often dismissed as a ‘trite poet’ and, lamentably, does not feature today on school and college syllabi. None of this takes from the fact that his Collected Poems sold over two million copies and that when he died in 1984, he had been England’s poet laureate for twelve years, from 1972.

This book is not just an inspirational, charming and entertaining account of Beckett’s time in, and life-long love affair with, Ireland but it is a passionate command to restore him as a major poet of the English language.

Betjeman In Ireland by Dominic Moseley is published in paperback by Somerville Press and costs €15.