Despite all the controversies in the run-up, and as with the last World Cup in Russia, most people are now looking beyond the politics, and enjoying the feast of football.

For many of those attending sporting fixtures, this is akin to performing a religious duty in a secular age. The rest of us generally slouch in front of TV sets and even squint into smartphones to satisfy compulsive appetites. In Ireland we have a particular grá for team sports as participants but mostly viewers, or even as virtual participants, with the advent of video games.

The rewards for sportsmen, in particular, are staggering, but many are left on the scrap heap at an early age, while others count the cost in later life with psychological and physical trauma.

"the World Cup itself is a bizarre and inexplicable thing. It temporarily requires even the most autocratic and despotic regimes to drop tools and play nice."https://t.co/ymOH6ZZPxB

This report from the 2018 World Cup in Russia is worth revisiting!— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) December 10, 2022

In History

The popularity of sports entertainment stretches far back into European history. The gathering of crowds for sporting occasions was a feature of Classical antiquity, when these spectacles were explicitly connected to religious worship. Held in honour of Zeus, the king of the gods, the Panhellenic Olympics of Ancient Greece ran from 776BC until 393AD, and attracted participants from across the Hellenic world.

Later, Romans were fanatically devoted to circus, which featured gladiatorial duals to the death. A note of caution was sounded, however, by the poet Juvenela c. AD100, who witheringly identified panem et circus (bread and circus) as the primary concern of the people:

iam pridem, ex quo suffragia nulli / vendimus, effudit curas; nam qui dabat olim / imperium, fasces, legiones, omnia, nunc se / continet atque duas tantum res anxius optat, / panem et circenses.

[… Already long ago, from when we sold our vote to no man, the People have abdicated our duties; for the People who once upon a time handed out military command, high civil office, legions — everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.]

Sport remained an important feature of life in medieval Europe, where knights tested their valour and prowess in vainglorious jousts. Hunting was also popular among the aristocracy at the apex of the feudal pyramid. Pursuit of animals, referred to as ‘game’, was generally not motivated by their value as food: consumption conferred status beyond gastronomic pleasure.

Pre-modern sports bore a close resemblance to warfare, and, the conditioning of a participant overlapped to a large extent with a warrior’s training, as one sees in ancient epic, such as with the funeral games of Patroclus in Homer’s Iliad. Tests of physical prowess, advantageous on the battlefield are evident, as well as skills such as archery and javelin, which are clearly a preparation for warfare itself.

The Funerals of Patrocle, oil on canvas. Jacques-Louis David, 1778.

Fight or Flight?

At a sporting event, an audience could experience the thrill of battle without risking dismemberment, although the qualities esteemed in the heroic athlete may have whetted a thirst for blood.

This may lead to an assumption that sport fosters a destructive, competitive instinct. George Orwell was of the view that: ‘sport is an unfailing cause of ill-will’. But denial of the amusement seems curmudgeonly. Sport can bring us together rather than tear us apart. Perhaps it depends on the underlying psychology of the crowd.

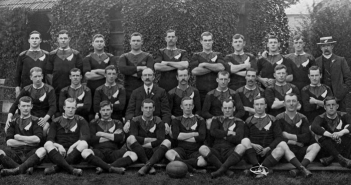

The nineteenth century incubated most of the sports that are now prevalent in our culture, including the GAA. It was in Britain, where the Industrial Revolution began in earnest, however, that mass attendance of sporting events by a new working class originates, as stadiums accommodating tens of thousands of people sprang up in a newly urbanised society. Here we find the codification of now global sports such as Association Football, Cricket, Rugby (Union and League), tennis and field hockey all of which now have a global reach. Others, such as golf and motor racing emerging in more rarefied environments.

Interesting, it is in the anglo-sphere that alternative sports emerged to confront the British invasion; in the United States, basketball, American Football and baseball; in Ireland the GAA developed our distinctive sports; even Australia and Canada developed or adapted their own codes. This demonstrates the importance of sport as a source of identity in the English-speaking world where other cultural markers such as food seem to have been of less importance.

The popular sports in our time depart from Classical and medieval precedent – notwithstanding the revival of the Olympics in 1896 – in the skills demanded of the participants. Although most contemporary sports still demand serious athleticism, their skills sets would be of no particular use to a soldier, especially one engaged in modern, technological warfare; although the skills of the gamer might prove very useful indeed.

Nonetheless, modern sports are still animated by martial fervour, accessing, and perhaps controlling, that primal instinct to compete and, for men especially, to discuss the competition. Orwell opines that: ‘At the international level sport is frankly mimic warfare’, but at that time most men, unlike today, had trained to be soldiers.

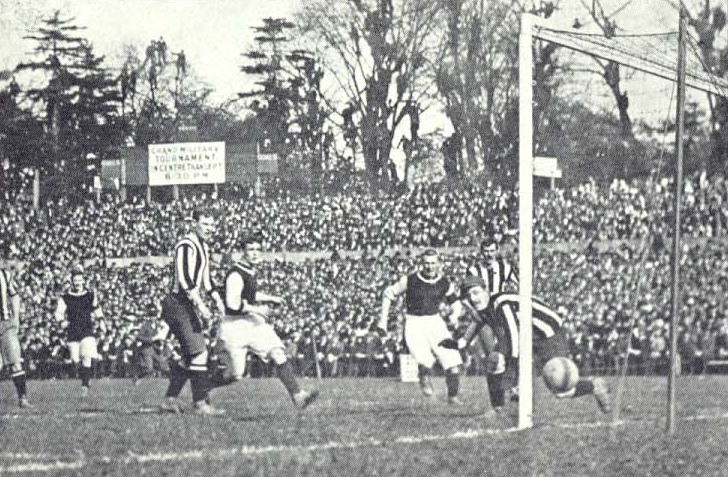

Harry Hampton scores one of his two goals in the 1905 FA Cup Final, when Aston Villa defeated Newcastle United.

Judgment

The demonic ‘Judge’ Holden in Cormac McCarthy’s no-holds-barred novel Blood Meridan (1985) describes war as ‘the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence’.

He argues that:

Men are born for games. Nothing else. Every child knows that play is nobler than work. He knows too that the worth or merit of a game is not inherent in the game itself but rather in the value of that which is put at hazard. Games of chance require a wager to have meaning at all. Games of sport involve the skill and strength of the opponents and the humiliation of defeat and the pride of victory are in themselves sufficient stake because they inhere in the worth of the principals and define them. But trial of chance or trial of worth all games aspire to the condition of war for here that which is wagered swallows up game, player, all.

The ‘Judge’ is right insofar as the higher the stakes the more gripping a sporting fixture becomes for an audience that puts aside its daily trials to vent their passions.

The worth of the participant is defined by their success or failure at crucial moments. But ‘the Judge’ is mistaken to assume that defeat is always a humiliation, as any crowd may honour a team or individual who loses with good grace, and sport is not only about winning; ‘greatness’ is also measured by how a loser conducts himself in defeat. Thus Harry Kane is above criticism despite missing a (second) penalty, while the Argentinian team are roundly condemned for rubbing defeat in their opponents’ faces.

Great photo. Classless team. pic.twitter.com/JusK2g0vsb

— Ewan MacKenna (@EwanMacKenna) December 10, 2022

Instinctive Selves

It is striking that Swiss psychologist Carl Jung regarded games as being of the utmost importance for the wellbeing of societies. He said that ‘civilisations at their most complete moments … always brought out in man his instinct to play and made it more inventive’. Sport, he proffered, connects us to our ‘instinctive selves’.

Sporting success can really raise the morale of a nation, such as the Irish after World Cup Italia 1990. The connection to a team or individual should not be dismissed lightly. Even in defeat, fans can summon a spirit of togetherness that is not necessarily oppositional.

The popularity of sports may be connected to the decline of religious worship, but the religious origins of sport have not faded entirely – fans often pay homage to virtues of self-sacrifice and togetherness associated with spiritual traditions.

Moreover, with lives increasingly sedentary and indoor, sport returns us to the idea of a challenge that melds innate athleticism and skill. This is both a natural gift, and the product of training.

The audience also enjoys the mental side of the game, considering how a team or individual will triumph or fail in advance of a contest, and assessing why a particular outcome has occurred in the aftermath. It can be the springboard for discussion between complete strangers, generally leading to camaraderie rather than conflict.

Sport has also become one of the last redoubts for mythology at a time when this generally operates on the margins, or in childhood fantasies. Commentators are given licence to rhapsodise about the divine characteristics of participants. We bow before sporting gods, satisfying a latent desire for non-rational explanations, and a taste for supernatural interference, deus ex machina: ‘the hand of God.’

Sports journalism, unencumbered by constraints imposed on ‘serious’ journalists, vents superstitions and often casually averts to curses; ‘legends’ abound in sporting parlance.

Why did Messi not get a yellow card? Listen people, let's settle this once and for all. When a football God like Maradona or Messi handles the ball, it is not his hand at work but the "Hand of God". This is football theology 101. pic.twitter.com/GRvXrhIRwc

— Dyab Abou Jahjah (@Aboujahjah) December 10, 2022

Titanic Battles

All this serves to enhance the appeal of ‘titanic’ battles, but sadly we are, increasingly, lured by the theatre away from examination of the vexed political questions of our time.

The assessment of Bill Shankly the former manager of Liverpool FC is worth revisiting: ‘some people say that football is a matter of life and death. I assure you it’s much more serious than that’.

It was therefore fitting then that when Jose Mourinho arrived in British football as manager of Chelsea FC in 2004 he chose to present himself as the ‘Special One’. For a time he carried all before him, with a little help from Russian billionaire Roman Abromovich.

Sporting occasions also offer a Dionysian alternative to lives that are increasingly constrained by social conventions. In what other arena of life can a grown adult scream and shout with unrestrained fervour, orr even streak naked across a pitch?

Sport imports a communal sense of belonging, evident in the crowd at a huge stadium and in the often transnational ‘imagined community’ of fans of a particular franchise. Support for national teams affirm a sense of belonging to the ‘imagined community’ of the nation.

The medium is the message. First television, and now increasingly the Internet, allows individuals, living thousands of mile away to support teams, often comprised of players from around the world.

Mythological themes are played out in real time. The truly great teams, it is said, are those that learn from defeat, just as the heroes of epic returns from the trial of Hades the wiser. We also encounter the tragedy of the flawed hero whose indiscretions are captured by the ravenous paparazzi, and attributed to the wider failings of youth.

English football fans at the 2006 FIFA World Cup.

Too Much of a Good Thing?

Yet we can have too much of a good thing. Attention to sports has reached pathological intensity. Slick marketing has moved an instinctive pleasure into a compulsive and easily-satisfied desire, activating demand in a manner that is almost pornographic.

In particular, the multi-billion euro football industry uses every available opportunity to lure child and adult alike into compulsive purchasing of television channels and merchandise that is gaudily flaunted. More troublingly still is the expansion of online gambling.

Young men are now paid unconscionable fortunes for playing games, which many would happily participate in for far less, or no financial reward at all. Televised sport used to inspire kids to imitate their heroes, now with gaming technology they don’t have to leave their couches, and the obesity pandemic carries all before it.

Rupert Murdoch recognised that sports would act as a ‘battering ram’ for his pay TV, an example most newspapers have followed. Sports coverage underpins a neoliberal zeitgeist by providing an alternative, apolitical, space with elements of tragedy and farce; villains and saviours; loyalty and betrayal.

Grandeur is evoked through metaphors such as the ‘trench warfare’ of a tight contest or the ‘phoney war’ of a friendly fixture; ‘citadels’ are ‘stormed’, and ‘no quarter is given’, along with specifically supernatural ideas such as ‘demons’ being ‘exorcised’. Stress is laid on the grandeur and importance of the events unfolding: thus we regularly learn that ‘history is being made.’ Too much of our lives, my own included, are absorbed by the spectacle.

With the degree of psychic energy devoted to the affairs of circus, it is hardly surprising that political involvement is increasingly the province of the paid-up professional; that the percentage voting has declined precipitously; that elections are explained by analogy with sporting fixtures; and that often warfare itself is relegated to the periphery. The widespread obsession is barely questioned by a media that feeds the fervour, and certainly not by politicians that display their colours to appear like regular guys.