John Philpot Curran

When the Federal Convention of 1878 had completed its work on the U.S. Constitution in Philadelphia, Benjamin Franklin described its result as, “A Republic, Madam, if you can keep it”.

Not much later, John Philpot Curran gave a similar warning, now usually summarised as “Vigilance is the price of liberty”.

Each was saying that a written Constitution describes how a country should be governed, but does not promise that it will be. If we want to keep the system we have chosen, we must be vigilant. A single departure may not seem very significant, but if we ignore it we may realise too late that it was a step in undermining our system of government. It is not enough for political leaders to be alert. In a democracy we are all political leaders, our system of government and the freedoms it promises belong to us, and if we want to keep them we must be vigilant to protect them.

This country has a democratic Constitution. Article 5 declares that it is to be a democratic state, and other Articles, read together, deliver on that promise. The Dáil is to be the dominant power in the Oireachtas. Elections for it must be held at regular intervals, so that we can dismiss political leaders who do not serve us as we wish. Elections must be by single transferable vote. The “sole and exclusive power of making laws for the State” is vested in the Oireachtas, the only limit being that its laws may not be “repugnant to the Constitution”. Laws are made in public, at sittings the public can attend and the media can report.

That our only lawmakers are those the People choose is the foundation of our democracy, as of every representative democracy. By adopting a Constitution that said that the only people who could shape the country by making law were those we had elected, we gave ourselves a democracy in 1937 – if we could keep it.

Leinster House the meeting place of Dáil Eireann.

Have we? Partly seems to be the best answer. The Oireachtas is no longer our sole and exclusive lawmaker. In the 1960s Irish judges began to adopt what is called “judicial activism”, the view that judges should play an active role in shaping the law. In 1965 the High Court advanced that view in the Gladys Ryan case. The Oireachtas had decided that it would be good for our dental health if piped drinking water contained a tiny proportion of fluoride, and enacted the Health (Fluoridation of Water Supplies) Act, 1960, under which piped drinking water was and is fluoridated. Mrs Ryan complained that this meant she and her children had to drink contaminated water, and took High Court proceedings to have the Act annulled. After a hearing lasting many months Judge John Kenny decided she had not proved that fluoridated water was injurious to health and dismissed her claim. But he made it clear that if he had formed a different view he would have annulled the Act.

That the case went to hearing is surprising. As we noted above, our Constitution vests in the Oireachtas the “sole and exclusive power of making law for the State”. Those words seem to mean that if a citizen thought an Act was defective her only resource would be to campaign to have the Oireachtas repeal or amend it. If another authority within the State could examine the reasons that led the Oireachtas to pass the law, disagree with them and annul the legislation, the power of the Oireachtas to make law would not be “sole and exclusive”. Those words seem to mean that the judge should not have heard the claim, because he had no authority to interfere with legislation that was consistent with the text of the Constitution. The Attorney General seems not to have made that argument. If so, he effectively abandoned the Constitutional authority of the Oireachtas as our sole and exclusive lawmaker. It seems never since to have been asserted in any Court.

The Judgment was a blow to the authority of the Oireachtas in another way. The effect of Judge Kenny’s decision was: “The Constitution includes a list of rights it guarantees to citizens, and the list is clearly not intended to be complete. Other rights may be added. The Oireachtas can add them. So can judges. A judge of the High Court or Supreme Court may decide to recognise a right that a citizen claims but the Constitution does not mention and deem that right to be part of the Constitution, as though it had been included in the document the People adopted in 1937. An Act of the Oireachtas or a Section of an Act that is incompatible with a right a judge has decided to recognise will be annulled as if it were repugnant to the Constitution, even though it is not”. (Rights so identified later came to be called “unenumerated rights, and we will use that term, for simplicity.)

The Ryan decision changed how we are governed, in three ways. First, judges could examine why the Oireachtas had passed legislation and interfere if they disagreed with its reasons. Secondly, the Oireachtas’ authority to make laws was no longer sole and exclusive, because judges might decide to recognise and enforce an “unenumerated right”. Thirdly, such a decision by a judge would override legislation enacted by the Oireachtas. That may seem to be a transfer of power from one organ of State to another, but it was an erosion of our democracy, because representative democracy depends on laws being made by those we have elected and by nobody else. Authorising people we had not elected and could not get rid of to override decisions of those we had elected was and is inconsistent with our claim to be a democratic state.

The Ryan decision also undermined our authority in a less obvious way. Our Constitution provides that only we, the People, may amend it, but when judges import “unenumerated rights” into it they in effect amend it. Our authority to do so is no longer sole and exclusive.

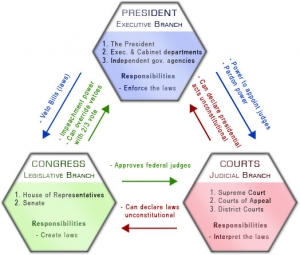

Separation of Powers.

Finally, it effectively changes the meaning of “separation of powers” and “separation of functions”. These used to mean that each of the three organs of government, the legislative, executive and judicial, had its separate function in which neither of the others should interfere. It now seems to mean only that the legislature and executive may not interfere in the judicial function.

There was no protest. We did not show vigilance in defence of our freedom.

Judges have invoked the “doctrine of unenumerated rights” (a “doctrine” is more impressive than a “theory”) many times since 1965. Unlike legislators, judges deal only with issues others bring before them, so they produce new “doctrines” or “rights” only if litigation gives them the opportunity. However, a substantial number of unenumerated rights have been established and a substantial amount of legislation annulled in the last thirty-six years. For example:

- Although all of the rights the Constitution lists except Habeas Corpus are promised only to citizens, that is only to people who, as it says, owe loyalty to the Nation and fidelity to the State, the Supreme Court decided to grant an “unenumerated right” to a non-citizen. (V.H. v. Minister for Justice Supreme Court No 31 & 56/2016)

- It forbade the Government to participate in a referendum campaign. (McKenna An Taoiseach & ors IESC 11; [1995] 2 IR 10.)

- It forbade the Dáil to conduct an inquiry into matters of public concern that might call for legislative intervention. (Maguire and others Seán Ardagh and others [2001] No. 329 JR; S.C. Nos. 324, 326, 333 and 334 of 2001] – the “Abbeylara case”.)

- On dubious grounds it invalidated legislation designed to protect young girls from sexual exploitation. C. v. Ireland & ors [2006] IESC 33

- It refused to hear a Habeas Corpus claim by a citizen who claimed to be unlawfully imprisoned, although the Constitution promises that right to anyone to making such a claim. (Edward Ryan v. Governor of Midland Prison [2014] IEHC 338)

- In a puzzling decision, it held that a police officer who is asked to approve a search warrant must act “judicially”, and that an officer involved in the relevant investigation cannot do so. The essence of us acting judicially is hearing both sides before reaching a conclusion. That does not seem to be what the Court meant, but it did not explain what it did mean. (Damache V. DPP {2012] IESC 11

- Although tradition and the Constitution both say that elected legislators in the Dáil or Seanad are to be free to perform their duties without judicial oversight, the Supreme Court decided that someone who claimed to have been injured by what had been said to her in a Dáil committee could pursue a claim. Kerins v. McGuinness & Ors. [2019] IESC 110

- One Supreme Court judge, Judge O’Donnell, complained in a written Judgment of the quality of legislation, in language reminiscent of an irritated employer complaining about incompetent subordinates. (Clarke O’Gorman [2014] IESC 72)

Each of these decisions further undermined the Oireachtas, and, through the Oireachtas, the Irish People’s power to shape the country we live in. Two of them, N.V.H. and Edward Ryan, are incompatible with the text of the Constitution. The list shows how much of our lives, which we agreed in 1937 should be governed by our elected legislators are now subject to the Court’s intervention – or interference. Again we have not shown vigilance.

Nor did those we elected to represent us. On the contrary, they have recently enacted the Judicial Council Act, which, after bringing the Council into existence, invited it to prepare “Guidelines” for compensation to be paid to successful plaintiffs in personal injury claims.

Superficially, that may have seemed rational. Individual judges decide what money should be paid as compensation for injury, so why should not judges as a group agree Guidelines to be applied, or at least consulted, in all cases? The answer is simple. Deciding what compensation should be paid to an injured plaintiff is administering justice, which is the role of judges. Guidelines to be consulted in all cases have the effect of law, even if they are given another name. Judges have no role in making law. Only the Oireachtas has. So in passing the Act the Oireachtas declined to perform a function that the Constitution imposes on it, and delegated it to a body that has no authority to perform it. This also meant that questions that elected parliamentarians should have teased out will not get the attention they need. Here are some examples. Readers may think of others.

- Personal injuries actions operate on an assumption that pain, past present and prospective, can be compensated for by money, and only by money. Is that assumption valid?

- If it is, is it right to assume that the extent of the pain, not the circumstances of the sufferer, determines the amount of compensation? €10,000 might seem a life-saver for a young couple struggling with high rent or mortgage and household bills, but be next to useless to a retired person living on an adequate pension.

- Our system protects a wrong-doer from having to address and acknowledge the consequences of his or her wrong-doing, because insurance companies forbid any contact between their insured and his or her victim. Does that serve us well? Would we drive more carefully if we knew we would have to confront personally the consequences of any carelessness?

The criminal court of justice, Dublin. Daniele Idini/Cassandra Voices

Most Superior Court judges nowadays are “Judicial activists” as described above. The concept is obviously attractive to judges and perhaps to others who believe trained intellects shape a society better than “ordinary people” could. But it is incompatible with democracy. That the Oireachtas invited a Council of judges to make law and the judges agreed tells us how far this country has travelled from the democratic ideals set out in our Constitution. Incidentally, the Guidelines emerged only after judges had circulated among themselves documents that they discussed in private, and that we did not get to see. With limited exceptions, our Constitution requires the Oireachtas and the judges to do their work in public, but, understandably, it did not consider how judges should do the work of the Oireachtas.

In this interview Professor Laurent Pech identifies the three stage process by which rogue EU states are undermining the Rule of Law and threatening democracy across Europe.https://t.co/YW85tanHgx@ProfPech @DLangwallner @broadsheet_ie @liamherrick @ICCLtweet @NMcDevitt

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) April 3, 2021

This article is critical of judicial decisions, and might seem to be hostile to our judiciary. Not so. Most of our judges are admirable men and women, with a deep understanding of the law and a strong commitment to justice. The purpose of each decision mentioned above (except the refusal of Habeas Corpus, which still seems incomprehensible) was to do justice. For a dedicated judge to deny someone justice, because our legal structure does not permit it must be disagreeable, almost like a physician refusing treatment to someone who needs it. Most judicial decisions were well motivated and most were beneficial to the community.

So, the argument that our precious democracy has been and is being eroded by decisions of judges does not mean we should denounce them. It would be wiser to suggest to them, politely, that our country would be better served if they respected the authority of our legislature more than they do at present, recognising that even a little judicial activism risks putting the judiciary in competition with the legislature and that carried to extremes it is inconsistent with democracy. If judges came to accept that, we can be sure they would act to address the problem. They are used to examining and evaluating evidence and arguments, and if the arguments stand up and are supported by the evidence, we should expect our judges to accept them, consider what they need to do to remedy the situation, and do it. If they accept that an imbalance has grown up between our organs of government that threatens our democracy, we can be confident that change will follow.

But if they do not, we should remember what Franklin and Curran taught us.