The degree of civilisation in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, The House of the Dead (1862).

The quote above is from a work of fiction, but the author was drawing on a memory of four years imprisonment, following conviction for involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle – a Russian literary discussion group of progressive-minded intellectuals opposed to Tsardom.

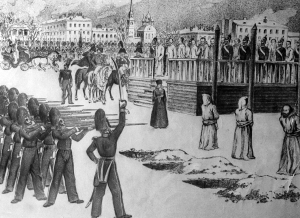

The great novelist only narrowly avoided a firing squad too – a stay of execution arriving at the last moment – which shaped his views on the death penalty. In The Idiot (1869) Prince Myshkin offers a salutary critique: ‘the whole terrible agony lies in the fact that you will most certainly not escape, and there is no greater agony than that’. He asks: ‘Who says that human nature is capable of bearing this without madness?’

A sketch of the Petrachevsky Circle mock execution.

For morals reasons – the idea of the state descending to premeditated killing – most jurisdictions no longer permit execution of prisoners following conviction for capital crimes. The strong likelihood of miscarriages of justice makes the argument against the death penalty appear insurmountable. A 2014 study indicated that one-in-twenty-five sentenced to death in the U.S. had been innocent.

The idea endures, nonetheless, that certain offences place perpetrators beyond the pale, incapable of redemption – diabolic even – wherein they are viewed as a perpetual threat to society, or even a moral contagion.

But, like it or not, the vast majority of prisoners do eventually re-join society, and it is in the wider community’s interest – with due regard for a victim’s or their relatives’ thirst for retribution – that convicts are rehabilitated to the extent they emerge as law-abiding and, ideally, self-sufficient citizens.

Given an estimated one in every two re-offend within three years of release in Ireland it appears the correct balance between punishment and rehabilitation is not being struck. A ‘Bibilical’ ‘eye for an eye’ view – reconciling moral accounts – still informs Irish attitudes to incarceration, with overcrowding exacerbating difficulties in an inadequate prison infrastructure.

According to Fíona Ní Chinnéide, of the Irish Penal Reform Trust in July: ‘At the outset of the pandemic, Irish Prisons were way overcrowded, you had people sleeping on mattresses on the floor.’

With courts resuming normal service, she feared prison populations would rise sharply, leading to further overcrowding: ‘I mean, in the best of times overcrowded prisons do not support rehabilitation and lead to increased tensions, drugs and violence, but Covid-19 brings an additional layer to this.’

Small Scandinavian countries such as Norway (20% after two years), Denmark (29% after two years) and Finland (36% after two years) currently lead the world in curbing recidivism. This can be attributed to prisons preparing inmates for life on the outside, including through open prisons that reintegrate offenders back into communities.

Slopping Out

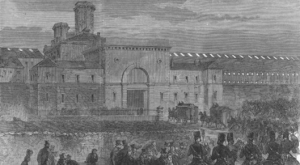

A de-humanization of prisoners is evident in the nineteenth century layout of Mountjoy Prison, the conditions of which could drive anyone to madness, or at least perpetuate a life in crime. Any visitor can discern a judgmental Victorian morality pervading the edifice.

Mountjoy Prison, Dublin 1850 Illustrated London News Public Domain.

The spectre of Henry Martin Hitchins, formerly Inspector for Government Prisons in Ireland, who oversaw its opening in 1850 lingers. He advised the first governor:

prisoners committed to your charge have been convicted of grave offences against God and man, that they have forfeited their civil rights and are confined much to protect society against their evil practices as to afford them an opportunity of repentance and reformation. It is therefore of primary importance that the prisoners should be brought to a proper sense of their condition and after the religious exhortations of the chaplains nothing so directly tends to effect this object as a firm and steady exercise of a severe discipline.

Inhumane features of the nineteenth century regime endure wherein the prisoner forfeits basic civil rights and experiences degrading treatment. Gary Simpson was held in Mountjoy Prison between February and September 2013. As a ‘protection prisoner’ he was kept in isolation from other prisoners – detained in cells on the D1 wing prior to its refurbishment. During that period there was no in-cell sanitation, nor even a sink providing running water.

Prisoners were normally provided with a ‘slopping out’ chamber pot and a plastic bucket of water for washing their hands. Simpson brought an action for damages in response, alleging he was regularly compelled to urinate into empty milk cartons as the chamber pot was too small to be used more than twice without being emptied. He claimed he had to defecate into a refuse bag for the same reason.

Simpson received damages of €7,500 in 2019 after contending with conditions the Supreme Court agreed breached a constitutional right to a basic level of dignity while in prison. The paltry nature of this award – commensurate with a soft tissue injury – is a damning reflection on the degree of Irish civilisation.

Disturbingly, despite a government pledge in 2017 to end the practice by this year, it was revealed in August that fifty-one inmates in Irish prisons are still slopping out.

It could be you…

Most of us, generally law-abiding citizens are not kept awake at night at the prospect of a stretch behind bars, but even among ‘respectable’ families there are often members who find themselves on the wrong side of the law. And delving into family histories invariably yields an ancestor who has offended against dominant morals expressed in the laws of the day.

In my own case, a great-grandfather Luke Armstrong (1853-1910) of Tubbercurry, Co. Sligo was subjected to at least two stretches behind bars for activities he viewed as political – the so-called Land War of the early 1880s – but which the Crown authorities considered criminal. An ambitious shopkeeper, ‘who was better dressed than his Tubbercurry companions,’ he was arrested in April, 1884 and charged with his fellow conspirators with being a member of the Fenian Society, and conspiring to murder a land agent.

An eviction during the Land War.

Luke Armstrong and his co-defendants were eventually transferred to Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, and brought to trial the following November at Green Street Courthouse. Thankfully, given the gravity of the charges, all the accused were acquitted based on the unreliability of the Crown informant’s evidence.

As a high-ranking member of the IRB, this was not Luke’s first brush with authority. He was also incarcerated in Enniskillen Gaol earlier in the 1880s where he was subjected to ‘two days’ solitary confinement by the Governor. Luke must have gained extensive experience of slopping out during these unwelcome sojourns.

The Land War of the 1880s may seem like a far off, almost mythical, period, but as recently as the 1940s Irish political prisoners were held – for years on end in many cases – without trial under Emergency Powers Orders in Nissen huts in the Curragh – labelled Tin Town (Baile an Stáin or an Bhaile Stáin) by internees that included the novelist Máirtiín Ó Cadhain.

According to the historian Tony Gray, the EPOs ‘were so draconian that they effectively abolished democracy for the period, and most aspects of the life of the country were controlled by the dictatorial powers the government acquired.’[i]

Ironically, another great-grandfather of mine, former Taoiseach (1948-51 and 1954-57) John A. Costello, was responsible for drafting emergency legislation while Attorney General in 1926 in response to the assassination of Kevin O’Higgins; although according to his biographer David McCullagh: ‘While portrayed as draconian, the response was in fact far more measured than might have been expected, or than was initially considered.’[ii]

At least, to Costello’s credit, in opposition when emergency powers legislation came before the Dáil again during World War II he insisted on a right of appeal to the courts from special tribunals.[iii]

John A. Costello 1891-1976.

Today, new emergency legislation in response to the pandemic awakens fears that “generally law-abiding citizens” could yet fall foul of draconian laws intended to protect the community. Indeed, the term ‘lockdown’ is derived from the lexicon of incarceration: the confinement of prisoners to their cells for all or most of the day as a temporary security measure. Perhaps our experience of stay-at-home orders will instil greater empathy with the loss of liberty and privations endured by a prisoner.

One should be hesitant, therefore, to assume prison to be the fate alone of an underclass or those exhibiting extraordinary moral deviancy. Any one of us could face a stint behind bars, either through weakness, as a result of a mistake or error, a miscarriage of justice, or even where a moral conviction leads to a stand against a law or authority we consider illegitimate.

In accepting this possibility, we should consider the minimum duty of care owed by the State to any person incarcerated, and the purpose of a prison sentence.

Principles of Sentencing

Objectives of sentencing include revenge, retribution, just deserts, deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation and restoration.[iv] The most familiar type of sentencing is a custodial sentence, but judges can also levy fines, or make community service orders; contributions to the poor box are often accepted as a form of contrition in lieu of sentencing.

The handing down of a prison sentence demonstrates to the community that morally repugnant behaviour will receive its just deserts. The threat of incarceration may also act as a deterrent, and a victim’s desire for revenge or retribution should be respected and vindicated.

The current conditions of Ireland’s prisons now amply provide for deterrence and revenge: who in their right mind would relish even a night in ‘the Joy’?

To an extent this is how it should be. Unless the State administers sentencing proportionate to a crime – as agreed by the community through its laws – faith could be lost in the rule of law. Indeed, vigilantism could emerge in its absence – as we have witnessed with extra-legal pursuit of drug dealers in some Dublin neighbours, and especially in Northern Ireland, where horrific kneecapping still occurs. The State should endeavour to monopolize the use of force with the objective of reducing violence, and other antisocial behaviours, overall.

Mandatory sentencing of ten years under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1999 for possession of drugs with a value over €13,000 has not, however, proved an effective deterrent and in most cases judges find exceptional circumstances apply to avoid the full imposition of the term for what is a non-violent offence.

It is understandable that judges would wish to avoid the nuclear option of a prison sentence, which often hardens individuals to lives in crime. If, however, Irish carceral institutions adequately rehabilitated young offenders in particular – nipping errant behaviours in the bud – judges might be inclined to prescribe short interventions. This could offer a chance for someone to turn over a new leaf, and even learn new skills in a safe environment.

Legislators might also consider broadening the range and reducing the period for convictions to be ‘spent’ – fixed at seven years for particular offences. This might diminish the social stigma of serving time behind bars, allowing for it to be seen as a therapeutic intervention rather than a lifelong stain on one’s reputation.

One means of addressing victim impact and an understandable desire for retribution or revenge is through non-adversarial mediation. This includes the idea of restorative justice, which brings perpetrators together with victims of crime. Ideally, a consensus is formed around what the offender can do to repair the harm caused by the offence. See Alan Gilsenan’s documentary The Meeting (below).

Anders Breivik

Incapacitation is also a necessary ingredient to sentencing, where an individual presents an ongoing threat to society, or even to fellow prisoners. This is a familiar justification for the death penalty, and there remain scenarios where an agent of the state – usually a police officer – acting in the common good, may lawfully kill someone, notwithstanding the twenty-first amendment to the Irish Constitution prohibiting the death penalty. Such a response is only lawful if it is proportionate to the threat – a test similar to justifications for self-defence.

Dostoyevsky’s moral argument, and the likelihood of miscarriages of justice, are convincing arguments against the death penalty, but the ongoing danger posed by individuals must still influence the severity of sentencing.

Thus, the continued solitary confinement of Anders Breivik – currently serving twenty-one years for a bomb and shooting attack that left seventy-seven people dead in Oslo – was not held to violate Articles 3 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, relating to the prevention of torture and inhuman or degrading torture, and the right to privacy and family life.

Flowers laid in front of Oslo Cathedral the day after the attacks. Image: Johannes Grødem

The test employed is one of proportionality. The court obviously took into account that Breivik is a mass murderer who had admitted to indiscriminate killing for a political end. Authorities fear he could exert a nefarious influence over fellow prisoners given an opportunity to do so. This view may be correct but it sets a dangerous precedent; albeit the Norwegian government argued that Breivik’s three-cell complex, with access to video games, TV and exercise facilities, is better than the conditions of most other prisoners, thereby compensating for his solitary confinement.

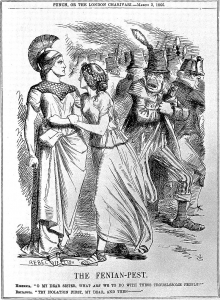

In recent times terrorism has emerged as a justification for harsher sentencing – and even torture – and extended periods of questioning before charges, but the definition of a terrorist is loose and unsatisfactory, and a form of structural racism (or Islamophobia) appears to inform treatment of offenders in many jurisdictions. My own great-grandfather was considered a Fenian terrorist in his day.

Satirical drawing, ‘the fenian-pest,’ Punch Magazine, 1866.

Open Prisons

The temporary removal of liberties such as conjugal rights between husband and wife is generally considerate a proportionate punishment when a guilty verdict is found. This view was upheld in Ireland in the case of Murray v. Ireland [1985]. But what if the denial of such a liberty impedes rehabilitation or the restoration of a flourishing individual to society? This judgment may merit re-examination if we are to prioritise rehabilitation.

The interest of the community in ensuring a prisoner is equipped to transition back into civilian life should trump an understandable desire for revenge felt by victims of crime and their relatives. But this reasoning does not now inform sentencing in Ireland, where even posting a letter requires a lengthy review process at either end. Enjoying the privilege of just one phone call a week means prisoners cannot easily stay in touch with family members.

Among the reasons for Finland’s low rate of recidivism is the open prisons developed to prepare convicts for life on the outside. Instructively, Finland has the lowest per capita incarceration rate in the European Union, with just 51 people per 100,000 in some form of prison, according to the World Prison Brief, while Ireland’s stands at 84 per 100,000, which might well be higher but for current overcrowding inhibiting sentencing.

The former prison building of Katajanokka, Finland is being renovated into a hotel.

Also, instructively, Ireland ranked sixth worst in Europe in a crime index conducted by Numbeo scoring 44.52, whereas Finland lies in thirty-fifth place overall on 22.80. Thus, despite a significantly smaller prisoner population, Finland is also a safer country than Ireland, scoring 77.20 against 55.48. Given Ireland’s GDP per capita ($89,383) exceeds Finland’s ($49,334) by a considerable margin, this is clearly a question of priorities rather than resources, and sadly, an indicator of our respective “degrees of civilisation.”

Sasu Tyni, a researcher at Helsinki University and the Criminal Sanctions Agency (RISE), says that the Finnish system is based on a belief that locking people up is a last resort. ‘Closed prisons are more or less grounded in security purposes, while open prisons aim to be closer to society, family, work etc,’ she explains. ‘The strategy of the Criminal Sanctions Agency has for years been to use closed prison as the last option. We assume an open prison system can decrease the risk of recidivism.’

Prison governor Kaisa Tammi-Moilanen explains that prison authorities have ‘purposely tried to avoid everything that we can which are associated with a prison,’ which means there are no physical barriers stopping prisoners from escaping. Tammi-Moilanen explains this is intentional, as it encourages prisoners to develop a sense of self-control.

Prisoners in a closed prison don’t need to learn any self-control, because everything they do is controlled. But to be a normal citizen you need to have inner control of your life, so you know how to behave, you know what is good for you and you know what is good for the society.

In contrast in Ireland, according to the annual report of the Inspector of Prisons from 2008:

At present the open prisons at Loughan House and Shelton Abbey are, to an extent, used to cope with the overcrowding in the closed prisons and therefore in their current use could only play a minor role in the effective management of prisoners through the prison system.

There is no evidence that international best practice has been taken into account since.

Reskilling

Re-evaluation of the role of Irish prisons does not appear to be on the immediate horizon. The new Minister for Justice Helen McEntee indicated that Garda reform, domestic violence and the modernisation of the sector’s IT services were her three priorities in an interview with the Sunday Business Post in August.

Yet historic shortfalls in rehabilitation have brought high rates of recidivism at significant cost to the exchequer: the average price of an ‘available, staffed prison space’ was €75,349 in 2019. Moreover, the lawlessness evident in parts of Ireland can be traced, at least in part, to the failure of the prison system to rehabilitate adequately.

Targeted investment should produce long-term savings by reducing recidivism. The new Minister thus has a huge opportunity to leave a profound legacy that could ameliorate conditions in certain ‘no go’ neighbourhoods.

Introducing meaningful open prisons to reintegrate prisoners into communities would require a cultural shift however. Prevailing Irish attitudes towards crime are informed by enduring social cleavages: in Dublin expressed in euphemisms about someone being ‘from the inner city;’ or ‘of Traveller origin’ in rural Ireland. Yet prison reform could address long-term poverty and social exclusion. Any progress would be a significant feather in the new Minister’s cap.

It seems obvious that prisons should offer inmates a chance to break the chain in a life of crime, rather than perpetuating one. Sadly, incarceration remains a breeding ground for criminality. Fresh thinking is required to address shortfalls in mental health provision, drug addiction counselling, and general education – especially illiteracy: one in six of the adult population in Ireland is still functionally illiterate.

In 1997 the Irish Times reported: ‘It is widely accepted that the standard of education of most inmates adults and juveniles is somewhere between third and fifth class of primary school.’ Twenty years later the same paper reported: ‘Overall, four out of five prisoners (80 per cent) left school before their Leaving Cert, more than half (52 per cent) left before their Junior Cert, and just over a quarter (26 per cent) never attended secondary school.’

Anyone hoping to leave a life in crime behind should be able to glimpse viable alternatives while in prison. A Leaving Certificate is generally seen as a foothold for advancing one’s career. In 2011 the Irish Times reported that 117 prisoners were sitting the Leaving Cert and 161 were taking Junior Cert exams that year, but current figures are not easily accessible.

Alternatively, offering prisoners business skills has been floated as one approach by chef-entrepreneur Domini Kemp, who participated on a programme at Wheatfield Prison. As she it put it:

I read that prisoners cost north of €68K a year in Ireland and it struck a chord with me that if you could teach them how to start their own business and reduce the rate of reoffending, how much you could save.

An entrepreneurial career path will obviously not suit every ex-prisoner. The challenge of starting a small business should not be underestimated. But the state should be empowering prisoners with career alternatives for when they return to their communities.

Mountjoy Campus, North Circular Road, Dublin, Dublin 7, Ireland

Wellbeing

In an enlightened society such as Finland’s it appears as if the traditional prison is being phased out. This may be attributed to many factors including an inclusive education system, as well as advanced ideas on wellbeing. Minister of Social Affairs and Health in Finland, Pirkko Mattila, explains the connection between economic growth and wellbeing:

Economic growth improves people’s wellbeing, whereas wellbeing and health of the population enhance economic growth and stability. This interlinkage must be better recognised. In Finland, we are putting forward a holistic approach to this question that requires horizontal thinking and cross-sectoral co-operation. We call this approach, the Economy of Wellbeing.

This holistic approach seems to play an important role in keeping crime to a minimum in Finland. In contrast the steady acquisition of wealth in Ireland appears to be decoupled from the Economy of Wellbeing. A more enlightened prison system could help bridge that divide.

Nevertheless, it may be impossible ever to extinguish the evil that leads to certain crimes. The example of Anders Breivik in Norway demonstrates that even highly civilised countries witness heinous crimes, or black swan events.

We may always require prisons to act as a deterrent and to protect society from evil behaviour, but it is worth bearing in mind that any one of us could find ourselves behind bars. It is in all our interests that prisons assist inmates to become functioning members of society. The Irish prison system is now perpetuating criminality, and the new Minister should make reform a priority.

Featured Image: main hall of Kilmainham Gaol.

[i] Tony Gray, The Lost Years: The Emergency in Ireland 1939–45 Little Brown & Co, London, 1997, p. 5.

[ii] David McCullagh, The Reluctant Taoiseach: A Biography of John A. Costello, Gill and MacMillan, Dublin, 2010, p.63

[iii] Ibid, p.139

[iv] See Frank Schmalleger & John Ortiz, Corrections in the 21st Century, 4th Edition, 2009, p.71