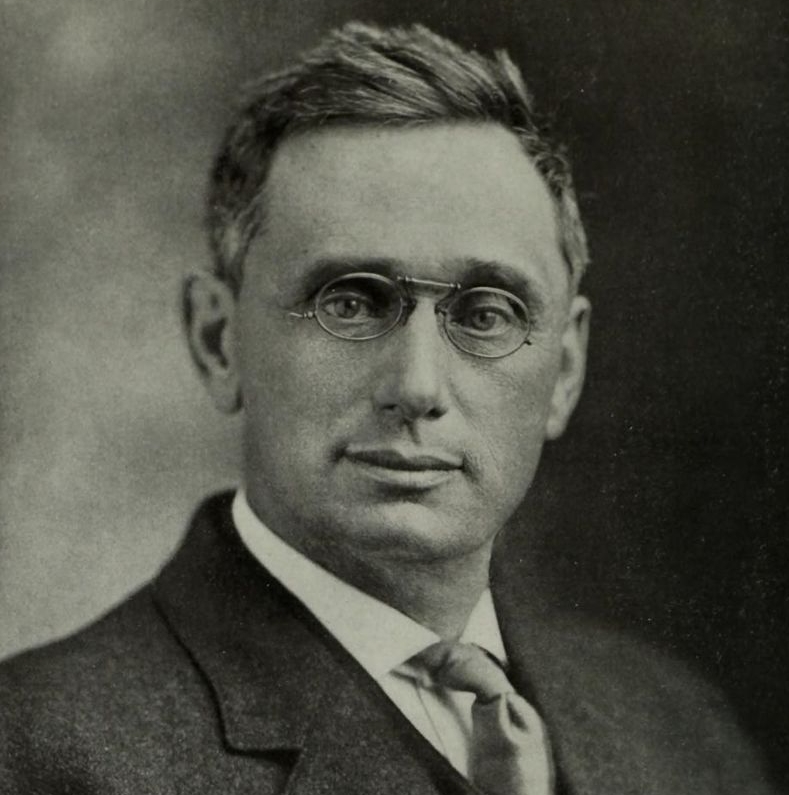

Both as a lawyer and Supreme Court judge, Louis Brandeis was an inveterate opponent of big business interests. Less well known than his other contributions, is that he a co-authored a text in the 1890 Harvard Law Review that invented a privacy right, which has steadily been eroded in criminal justice.

Indeed, as a judge in Olmstead v US Brandeis extended the privacy right to what he termed ‘the dirty business of the state’. In that case, without judicial approval, federal agents had installed wiretaps in the basement of Olmstead’s office and in the streets near his home.

Culminating in the recent Quirke case, in Ireland, a right to privacy in criminal proceedings has now reached a juncture of virtual nonexistence.

In my last article I referred to Irish Supreme Court Justice Gerard Hogan’s opinion that for thirty years the Irish Courts have failed to enforce due process under Article 38 of the Irish Constitution. The Quirke case delivers us to the terminus, facilitating the dirty business of the state.

In that case, evidence gleaned from a computer unlawfully seized from Patrick Quirke’s home was deemed admissible. Jurors in Quirke’s original trial were informed that Quirke’s computer was used for internet searches on the decomposition of human remains and limitations of forensic DNA. Quirke was found guilty of murder based on circumstantial evidence.

No Statutory Safeguards

In Ireland we now enjoy no statutory safeguards, other than Judges’ Rules, whereas in the U.K. Section 76 and Section 78 of PACE (The Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984) are actively enforced to exclude coercive and inappropriate tricks or force, and that which impacts on the fairness of the proceedings. I know from experience that judges in the U.K. are vigilant at throwing out a case in the event of an abuse of process.

The murmurings by the Irish government about the implementation of the Special Criminal Court recommendations is a space which should be carefully watched. Most likely, in my view, is that an institutional preference for non-jury courts will be given ever-wider jurisdiction.

It is a sign of how we are entering an inquisitorial rather than adversarial age worldwide, not just in Ireland, which suits the interests of many of our elites. Our own, and other states, are sidestepping the Rule of Law in the interests of big business, often at the expense of the sometimes-innocent lives of others.

Furthermore, it is noticeable that the seven judges of the Supreme Court selected to adjudicate on the Quirke case did not include the state’s leading constitutional lawyer. Gerard Hogan’s absence was his presence.

One can only wonder why Hogan was, deliberately or otherwise, excluded. Perhaps to preserve a show of strength through unanimity? Or maybe Hogan would rather colleagues were unanimously wrong, and wanted no hand nor part in it.

While on the High Court Peter Charleton was the architect of the nefarious JC case. His judgment in Quirke expressly reinforces that case, and fails to over-rule it as doctrinally unsound. He also sidesteps accepted breaches of EU and ECHR data protection under the privacy right. The judgment effectively subsumes a right to privacy at the expense of public order considerations, and legitimates the dirty business of the state.

The Supreme Court could have engaged in a process of reconsideration and followed the late Adrian Hardiman’s masterful dissenting judgment in JC. They had a choice and did not.

Hardiman’s absence is also his presence. The shade of a forgotten ancestor. His dissent is not even addressed in any satisfactory detail in Quirke. This failure to address Hardiman’s reasoning is not dissimilar to the way the State treats whistleblowers, who are demonised, ignored, trivialised or excluded. If all else fails, as in the McCabe inquiry which Charlton presided over, the State endeavours to deflect, invoking the shabby excuse of inadvertence – at least until confronted by the stark truth.

Then, only after being caught with your legal pants down, do you cobble together a shabby deal involving a multimillion pound pay out. With a confidentiality agreement of course.

Image: Daniele Idini

Factual Matrix

The factual matrix of Quirke may go some way towards suggesting that it was an inadvertent mistake, but that is not a typical pattern, as various sources, including the Morris Tribunal, and Hardiman’s eviscerating judgment in JC, demonstrate that discipline – and it might be said ethics – are barely apparent in the Irish police force: An Garda Síochana.

It is not a case of – as I can testify – simply of incompetence, though this is undoubtedly part of the problem. It is a combination of tunnel vision, or cognitive bias, coupled with active attempts to frame those deemed to be threats, or perceived threats.

Whistleblowers, including and especially internal ones, are a particular target, but human rights lawyers or defence counsels may also be in their line of fire.

There is no point having the symmetrical precision contained in Charleton’s detailed judgment and in some of the majority judgments in the JC case. This is not a case about shipping or guarantees where rules can be implemented precisely with clear consequences; and where high commercial stakes demand clarity and precision, which can then be cross-checked against best practice in industry.

The rules in criminal proceedings must be matched up with, and adapted to, social realities. A member of An Garda Síochana may describe something as inadvertence when it was a reckless or deliberate violation of constitutional rights. There is a consistent tendency to lie or cover up. That is what the Morris Tribunal and other reports demonstrate. Things have got worse not better. This was not dealt with adequately in the Report of the Fennelly Commission.

Image: Daniele Idini.

The Path of The Law

In one of his most celebrated contributions to legal discourse Brandeis created the so-called Brandeis Brief, which is often used in cases involving the death penalty, and others. This involves the marshalling of economic and sociological data, historical experience, and expert opinions to support legal propositions, i.e. judgments must be cross-checked against social realities.

Therefore, in Ireland the behaviour of the police does not warrant a watering down of the strict exclusionary rule. In Ireland we require a high standard. Discretionary rules will not be applied.

If the police are afforded the excuse of inadvertence, they will happily paper over illegality.

Rules must be informed by social realities. It was recently alleged in the High Court that a number of officers supervised the importation of drugs, and controlled the flow of shipments to dealers. Woe betide anyone who has the temerity to stand in their way.

Charleton by implication, and expressly, suggests that a factual inquiry into the bona fides or honesty of a police action and decision can be made in a specific context. But given the present Special Criminal Court dispensation, accepting uncorroborated police evidence, that inquiry must be very limited and conditioned by the judgement of subjective officialdom.

The acceptance of a Garda evidence in even securing a warrant without adversarial scrutiny is unacceptable. Safeguards need to be built into the system.

The Quirke judgment is a travesty: a neatly-ordered, precise and tidy travesty – as is Charleton’s want. We should not be facilitating the dirty business of the state but enforcing the privacy right.

Feature Image: Daniele Idini