I sat for a while by the gap in the wall

Found a rusty tin can and an old hurley ball

Heard the cards being dealt and the rosary called

And a fiddle playing “Sean Dun Na Ngall”

lyrics from ‘The Broad Majestic Shannon’ by Shane MacGowan.

I wasn’t close to Shane – celebrity brings an understandable reserve – but he was someone I hung out with in latter years, travelled alongside, and helped take care for a short time.

I have also been told he gave a typically back-handed compliment to an article I wrote describing his last trip to London for the launch of an exhibition of his art work: “God he’s a windbag, but then so was James Joyce.” Needless to say, I am still chuffed. Alas, he was rather less enamoured by my amateurish songwriting – which I recall later in this piece. This at least provides some reassurance that he wouldn’t give a compliment unless he meant it.

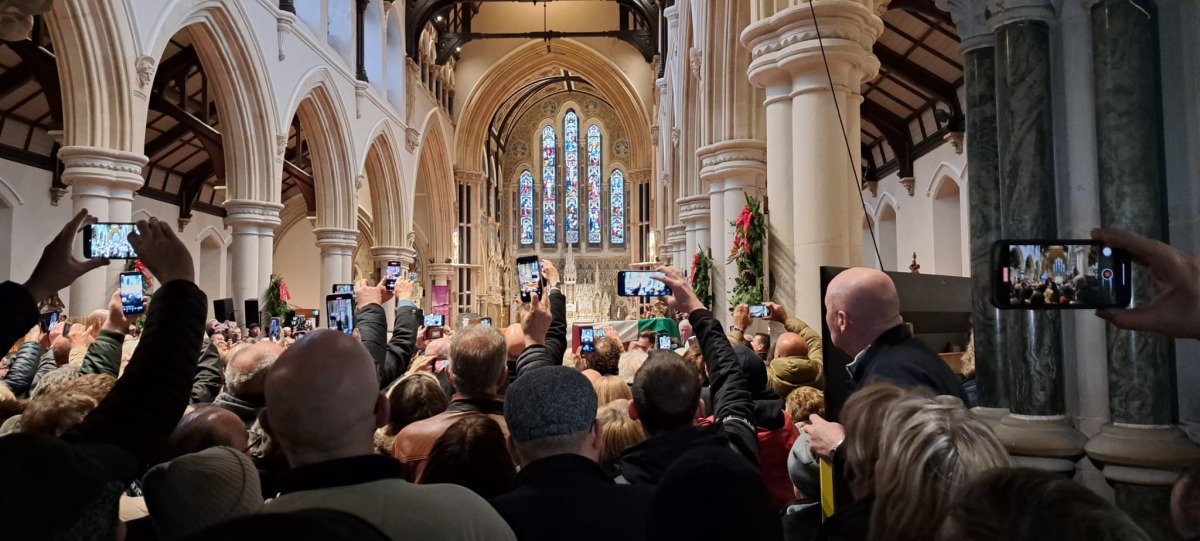

Shane MacGowan‘s funeral mass on Friday, December 8 might have re-awakened a Catholic faith in its most ardent opponents, while conservatives regard it as scandalous. Who else could have summoned leading mourners into dancing joyously before the altar, after a sublime ceremony that merged tradition with frivolity, and formality with raucousness? In death, as in life…

Holy Mary Mother of God / pray for us sinners / now until the hour of our death…

In Shane’s mind, Mary was a powerful female icon. A warrior woman, ‘Calming her people’. He was capable of reconciling – as only a poet can – anger at the Church over covering up paedophilia, and what he viewed as a betrayal of the Irish Revolution, with a simple Catholic faith.

As with many second-generation Irish emigrants, Catholicism seemed intrinsic to his identity. Importantly, this was a choice rather than an imposition. However, while his heart throbbed with a paradoxically profane Catholicism, this was not to the exclusion of other faiths and traditions. The array of deities, daemons and angels festooning his mantlepiece suggested syncretic beliefs. Spiritual nourishment was maintained by a steady supply of pre-blessed Eucharists, ferried up from Nenagh. Shane could always get his hands on the best stuff.

Importantly, once the wild touring years with The Pogues had drawn to a close, he decided to move to Ireland to take up residence in his mother Therese’s (née Lynch) ancestral cottage in Carney Commons, County Tipperary.

Having been born in Kent, he could easily have lived out his days in England, mournfully recalling the old country, but Shane remained ‘Loyal, true and faithful’; coming home like a Fenian prisoner ‘From dying in foreign nations’. Even the demise of The Pogues can partly be attributed to his insistent Irishness: creative differences emerged when others in the band, many of them with no Irish background, proposed moving beyond an Irish sound, as the documentary If I Should Fall From the Grace of God – The Shane MacGowan Story reveals.

He returned, as he saw it, to Ireland when the Celtic Tiger was in full roar, restricting the pre-modern society he had encountered as a youth to the margins. It’s fair to say he struggled to reconcile himself to a brash, individualistic and increasingly homogenous society, but never departed.

Patrician and Spailpín

The Romantic poet W.B. Yeats and the Punk singer Shane MacGowan might be viewed as being at opposite points on a spectrum of Irishness: one epitomising a patrician Anglo-Irish literary tradition; the other a performer representing what Joe Cleary has described as the ‘spailpín [lit. ‘journeyman’] culture’ of ‘hard labour and hard living, of wandering and exile, resentment and loss … nurtured by two languages.’

Thus, when declaring his will in ‘The Tower‘ (1928), Yeats portentously claimed to be one of the ‘people of [Edmund] Burke and of [Henry] Grattan’. He also scorned ‘Porter-drinkers’ randy laughter’ and the ‘base born products of base beds’ in his valedictory ‘Under Ben Bulben‘ (1928).

In contrast, Shane MacGowan explicitly portrays ‘the slaves that were spat on’ from the Tower in his song – based on personal experience – about rent boys, ‘The Old Main Drag’ where the protagonist is ‘spat on, and shat on and raped and abused’. His oeuvre positively celebrates intoxication and fornication, although he was in many respects even more of a romantic, as tracks such as ‘A Pair of Brown Eyes’ and ‘The Song with No Name’ attest.

I heard Shane express his dislike of the Anglo-Irish poet – although he did record a version of Yeats’s anti-war poem ‘An Irish Airman Foresees His Death’. He preferred the aesthetic of Brendan Behan in particular.

There is, nonetheless, a striking parallel. Both poets while living in London a century apart, consciously embraced their Irishness, which helped each of them develop distinctive voices. Yeats would no longer simply be a Romantic poet in the mould of Wordsworth: he forged a distinctively Irish Romantic tradition. Likewise, MacGowan would no longer be another Punk singer in the shadow of Johnny Rotten: he became an Irish Punk balladeer, and an inspiration to a rising generation of distinctively Irish song-writers.

In his autobiography, Yeats describes walking homesick through Fleet Street in the 1880s and hearing a little tinkle of water, whereupon he saw a fountain in a shop window which balanced a little ball on its jet that reminded him of lake water. ‘From that sudden remembrance’, he wrote, ‘came my poem “Inisfree,” my first lyric with anything in its rhythm of my own music.’

A body of water provides the title for perhaps MacGowan’s most poetic song, ‘The Broad Majestic Shannon’, which features an aging Irishman dwelling on his youth in County Tipperary after many years of living in London. The rusty tin can and the old hurley ball is Shane recalling his own childhood. It’s a song that also conveys homesickness, joining Shane MacGowan’s soul to the great river of Ireland flowing through Tipperary – where his ashes are to be scattered – just as places in Sligo will forever be identified with Yeats.

Perhaps one day tourists will flock to The MacGowan county, just as they travel from far and wide to The Yeats County.

Protest Song

A few years ago a good friend of Shane’s and I took a song we had composed to him. It was a naive protest song about the government’s inaction on public transport that appropriated a melody from another song about trains popularised by Johnny Cash, called City of New Orleans. I added a few verses in a different key and thought perhaps it could work.

I continue to maintain that my friend’s decision to bellow it a capela was fatal to its reception. A little guitar might have taken the edge off it. In any case, Shane became apoplectic, demanding he stop singing, and immediately identified the source of the melody.

I guess you don’t become one of the leading lyricists in the world without having finely honed critical faculties. Having trawled my hard drive I can find no evidence of the recording I made of it, which is probably for the best!

It would have been nice to sing more songs with Shane, but he seemed depressed a lot of the time, and expressed frustration at a writer’s block that was inhibiting him. At least when we were travelling to London there were a few sing-songs, but it was clear then that the isolation and inactivity of the Covid years had taken a toll.

The scene before the funeral mass of Shane MacGowan in Nenagh.

Regrets

I hung on Shane’s every word, but he wasn’t the easiest of company. At times, I felt awkward about not being able to make out exactly what he was saying. A self-preservation instinct may also have inhibited me from being drawn too closely into his orbit. The atmosphere could be heavy and a bit self-destructive if you weren’t careful.

It wasn’t that he was drunk all the time. As he once put it, tongue-in-cheek, on the Late Late Show when he was interviewed by Pat Kenny: “in England I’d be regarded as an alcoholic but in Ireland I am a sissy drinker”.

He always seemed to have a drink in front of him, but was a sipper, abiding by certain rules agreed with Victoria. As she alluded to in her remarkable eulogy at the funeral, there are lessons on addiction to be drawn from Shane’s example.

Being drunk – playing the fool – might also have been part of Shane’s public persona. Exhibiting intoxication could also mask the insecurities of a savant or autodidact, who was expelled from school in his early teens. His reading and creativity were haphazard and unsystematic, and worn lightly. I suspect he would have been intimidated by haughty scholars interrogating his work.

Shane spent most of his final months in hospital, but I didn’t feel up to visiting him as my own father had passed away in the same hospital the year before. Anyway, I had the impression that a steady stream of friends and admirers were at hand.

Eternal rest grant unto them, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them. May the souls of all the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.