The story of subliminal messaging follows an interesting evolution, one infrequently told about a technique that may have created a monster. Considering this technique in the context of advertising, we can trace its roots back to the post-war 1940’s and 50’s United States. In so doing we must set the stage and, as Voltaire insists, ‘define our terms’.

Post-war America was undergoing an unprecedented economic boom. Manufacturing was in the ascendancy and incomes rising as never before. Modern capitalism was struggling through the birth canal of history and media-advertising was to be its midwife. The somnolent frugality and penury that defined the war years, and especially the pre-war Depression, was steadily usurped by a ‘terrible beauty’; the ‘American dream’ was assuming a material reality in cars, clothes, movies, music, diners and jukeboxes , enterprise, technology and invention; so much and more was coming out of America, and much of the world looked on with envy.

Post-war America thus experienced an explosion in new media; of television, radio, magazines connecting capitalist aspirations, with revenues increasingly derived from advertising.

Those behind the advertising fuelling American economic growth were fondly known as the ‘ad-men’. It was their job to motivate particular behaviours within a newly financially empowered individual, increasingly referred to as the ‘consumer’. Citizens had evolved into civic and economic units, with civic and economic or consumptive obligations. Consumption, despite being a euphemism at the time for the ravages of tuberculosis, was to become the bedrock of democratic capitalism.

By the late 1950’s and early 60’s, however, these consumers had begun to satisfy many of their material wants with products that initially endured, leading to new and more targeted influences. Rather than satisfy real and prescient needs, it became the job of the advertiser to ‘get inside’ the consumers’ minds and encourage them to think and feel differently, about each other, about the world, and about products.

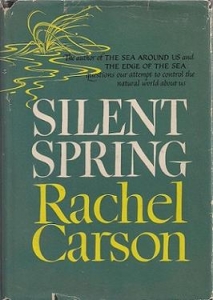

America at the time was rich in oil, steel, lumber, agricultural lands and innovation. Resources were not unlimited, but they appeared so. Notions of conservation, environmental protection, biodiversity or climate change, were barely on the table, at least until Rachel Carson’s seminal Silent Spring was published in 1962.

During those halcyon days the Republican mantra of ‘trickle down economics’ had some substance, as there appeared to be an overabundance flowing down the social ladder. Even ‘socialism’ in respect of constructing roads, schools and other infrastructure enjoyed a share.

Planned Obsolescence

By the early 1950’s, however, it appeared to the captains of industry that the consumer market was becoming saturated. After large sections of the white middle classes had purchased a fridge, a car, a TV, a washing machine and other consumer durables, insiders feared the economy might be headed for a crash. Consumers might purchase enough material conveniences, but would soon begin to purchase less! Limitless economic growth might eventually come to an abortive and premature end.

The widespread prevalence of this fear cannot be overstated. One researcher writes:

There were disturbing indicators: for instance, between 1940 and 1950, the proportion of American families with mechanical refrigerators increased from 44 to 80 percent. Indeed, such ravenous consumption of homes, cars, and other goods meant that by the mid-1950s, marketers and businessmen feared, the saturation point was at hand. This fear led to two important marketing innovations. Planned obsolescence, the intentional design of goods to be short-lived, provided consumers with a reason to buy replacement items and created trends that promoted “keeping up with the Joneses.”[i]

Market segmentation arose from the theory that consumers had different preferences, rational and irrational, influencing their purchases. Advertisers began to target consumers on an individual level in order to market goods. These innovations helped advertisers to differentiate products and more successfully market them.

In The Affluent Society (1958), economist John Kenneth Galbraith condemned advertising for creating ‘wants that previously did not exist,’ but recognized its importance in stimulating the consumption that had generated post-war prosperity. Thus, between 1946 and 1955, the amount of money spent annually on advertising in the United States nearly tripled, from $3.4 billion to $9 billion. Consequently, throughout the post-war period, the ad man’s ‘real and perceived abilities to influence politics, culture, and the economy steadily grew.’[ii]

This makes sense: people don’t need to purchase products they already own. Fuelling the fears of a crash, was the reality that products were initially being made to last. Everlasting nylons, everlasting light bulbs, cars and machines with serviceable or repairable parts; permanence and durability were great ideas in the early days, but these ideas soon became dangerous with unfettered economic growth in mind.

The legacy of this revision is now all around us in terms of the environmental costs, and the ‘Growth Delusion’ has been extensively written about. (See Richard Douthwaite’s The Growth Illusion, Lilliput Press, Dublin, 1992) An irony emanating from this era is the permanent shift into our present reality of ‘planned obsolescence’. If products refused to wear out they would need an inbuilt expiry date. One might say with reasonable confidence that from the 1950’s the most enduring material artifact of manufacturing, has not been products, but landfill and human waste.

The task of the ad-man thus evolved from satisfying existing practical needs into creating new ones. Ideally, the ‘need’ for products that would gracefully expire and require replacement. If the products themselves refused to wear-out they would be portrayed as ‘outdated’, ‘outmoded’, or even an embarrassment to the owner.

The enduring, and egregious reasoning for dumping millions of tons of functional material products, in place of more ‘fashionable’ and ‘modern’ alternatives, slowly and effectively became normalised.

To all but the old-school farmer, this modern notion of ‘fashion’ as an important feature of function, persists to this day. The techniques for sustaining this ideology are taught in most universities. Of itself ‘fashion’ is perhaps a strange ideology and so-called ‘fast’ fashion is of course one of the largest contributors to the mass production of human waste. Thus an environmentally inimical notion of style emerged ascendant, and is now practically unassailable. Any questions of the cost or necessity of ‘fashionable’ apparel can readily be dismissed as outmoded.

Freud’s Nephew

This juncture in the history of advertising is best illustrated by the career of Edward Bernays – the nephew of Sigmund Freud – perhaps the most famous ad-man in the history of media. His influence as one of the founders of the ‘science of advertising’ is detailed in a BBC documentary: ‘The Century of the Self.’ He made use of Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis throughout his career to develop marketing strategies that have come to define the industry to this day.

For the advertiser or student of media ‘getting inside the mind of the consumer’ is perhaps an entirely reasonable objective. And yet, when we pause to think for a moment, how many of us would be wary of someone proposing to ‘get inside our mind’?

Bernays most famous use of these ‘new’ psychological techniques, was during his professional association with the tobacco industry. At the time in America, and indeed in many Western countries, most women did not smoke. The practice was socially frowned upon. If they could be encouraged to start smoking, profits would potentially double.

Ingeniously, Bernays effectively enlisted the women’s suffrage movement, by fostering a notion that not smoking was a sign of women’s oppression. His campaign implied that social stereotyping was preventing women from smoking, and that it could become an expression of their equal rights.

This perhaps intimates a familiar failure within feminism, which is the pursuit of equality rather than creating a practical respect for difference. A persistent desire to achieve equality with men, raises women no higher than equality. It sets the bar at the level of ‘man the trousered-ape’. Feminism rarely permits itself to go beyond men, into the realm of an overdue respect for female distinction, especially motherhood.

If men can smoke, then women should be free to do so also. The idea is simple, it contains a simple truth, but is hardly reflective of anything truly ‘feminist’ or ‘feminine’. Here we encounter the original ‘evil’ of the Sophist; the attempt to prove a facile argument by using true facts.

Whatever one’s views on the link between women smoking and their oppression, Bernays’s conversion of smoking into an assertion of equality, was unquestionably marketing genius. It should also be recalled that the harmful effects of heavy smoking were not then as widely accepted as they are today.

A decisive moment in Bernays’ campaign was when he enlisted a group of women to march in the Easter Sunday Parade of 1929. At a pre-ordained moment the women halted the parade, lit up cigarettes and puffed away.

Bernays and the tobacco industry temporarily re-branded cigarettes ‘torches of freedom’ The artfully manipulated ‘scandal’ had the desired effect, connecting smoking with female empowerment, and within a few years, a woman’s ‘right’ to smoke had been largely conceded. The tobacco companies were laughing all the way to the bank.

The successful marketing of cigarettes as progressive statements of liberty, female emancipation or a sign of Western sophistication, continues to this day in Africa and in the Middle East.[iii]

1890s satirical cartoon from Germany illustrates the notion that smoking was considered unfeminine by some in that period.

Old Socrates and the ad-man/Sophist

Of course ‘sublimation’ has a longer history than Bernays and the Manhattan ad-men. One might ask, what exactly does it mean to be a ‘victim’ of subliminal messaging? And when or if the victims deny they have been wronged then the delusion is complete.

Sublimation might be defined as some kind of ‘subversive mind control.’ Yet, perhaps the process is not a dark or subversive tool? Perhaps it is intrinsic to the functioning of group psychology. It may be integral to how our shared beliefs are transmitted, become established and are continually reinforced through a collective and instinctual need for belonging?

When misappropriated this ‘process’ of sublimation, becomes what Freud referred to as ‘mass psychogenic delusion’[iv] or what is sometimes described in Psychiatry as a ‘conversion disorder’. Certainly, when particular ideas are introduced into the sublime – the subconscious mind – there is often no limit to the evils they might engender there.

The ‘message’ is about getting us to behave in a certain way, to convince us to move in a particular direction, despite, or even in contradiction to external evidence, or our own better judgement. Yet this type of definition is equally unsatisfactory. It simply transfers the objective criteria for these newly fostered ‘needs’ to an external place; to someone else, to an ‘outside-of-self’ analysis of what one’s needs really are. This outside or objective ‘other’ must then decide what one’s thinking would normally be, if one’s mind had not been manipulated in the first place.

If I am aware that I am being deceived, I am hardly being deceived. And if someone tries to tell me that I am being deceived, (as with Plato’s cave dwellers), I might prefer to continue with the deception, before having my gullibility exposed.

If someone is apparently thinking or acting against their own better judgement, he or she will require an ‘other’ to identify this for them. It’s a classic Catch-22. If I am to realise that I am mad, someone else must tell me, or I must figure it out myself. If I’m sane enough to figure out I’m mad, I cannot have been that mad in the first place.

Whilst we are ostensibly guided by our own reasoning, we cannot know that our reasoning is being manipulated. Once we become aware of the manipulation; once we have recourse to our own ‘better judgement’ the spell has been broken. But it takes a brave soul to declare to the world: ‘I am being manipulated; I am being controlled or motivated by the ad-man.’

The essential deception contained within all forms of sublimation, therefore, is the requirement to make the subject believe that his newly fostered belief or desire, has not been caused by the advertisement itself. The advertisement has not caused us to desire a product, but has simply reminded us of an endogenous internal need, one that is entirely one’s own. The ad-man like the sophist has proven a false need by using true facts. The need in this case is only true by virtue of the unspoken fact that we have come to believe its ‘truth’.

The fostered desire must be hitched to our own desires, our inescapable instinctual imperatives; our desire to be happy; to live in accordance with reason; to be moral and just; or to be loved, accepted or respected by others. The ad-man must encourage us to ‘realise’ autonomously that life will be better, once we go ahead with the purchase.

There is of course a strong internal bias here. If I admit that my needs are not my own – that they are not genuine but have been hijacked by another – I must then admit to a sort of mental weakness; a failing on the part of my brain or intelligence. It is far easier, and safer, to assume and even insist that my beliefs are my own. That I am too intelligent to be ‘brainwashed.’

The Sophists

Sublimation is as old as civilisation. Socrates was convinced that we never really ‘learn’ anything at all. He believed that all important knowledge is within our minds at birth. That it is merely brought into being or delivered into the world. The midwife in this process is the philosopher. Socrates believed the challenge does not lie in the introduction of novel thoughts or ideas, but rather in altering how we go about our thinking. His solution is a Socratic methodology of thought.

Learning how to count presupposes (in the Socratic sense) an innate knowledge of relative numbers, this knowledge is something that we are born with, and do not acquire. We simply learn how to express and use that knowledge, to apply it in the pursuit of mathematics.

The structure of language might equally be considered an innate tool, as Noam Chomsky argues with the idea of a universal grammar. It is useful in helping us describe our thoughts, but we do not require language in order to have thoughts. We do not need to formally learn how to engage the process of thinking. Language might help us express our thinking, but we are born with an ability to think, and merely learn to express our thinking through the tool of language.

For Socrates, learning how to think is a relatively simple matter. There is a good and bad way of thinking. The benchmark for success being its independent approximation with truth; an absolute truth, a priori, unique, unassailable and independent of man. In the Socratic sense, truth is attainable through reasoned independent thinking: in other words, through philosophy. Independence in thinking was, however, an anathema to Socrates antagonists the Sophists. It remains an anathema to the ad-man, independent thinkers are rarely fashionable.

The main point here is that Socrates is of the belief that there is a distinction between acquiring information or skills, and understanding or correct thinking. What we should ‘do’ with information as it is acquired or learned through our senses, is already known to us innately. The truth is already within us, it is the ‘good as such;’ the ‘good’ in all of us. It is not acquired or purchased from another. It need only be brought into the world by learning how to think correctly, independent of any motive other than truth.

So here’s the rub, the crucial distinction between Socrates and the Sophists is that the Sophists were uninterested in an internal, a priori truth or the ‘good as such’. They defined ‘good’ as being in the realm of the external, material world. In simple terms, they correlated ‘good’ with success and power. ‘Justice is what is good for the stronger’ is the first Sophistic argument that Socrates refutes in the opening chapter of Plato’s Republic.

For the Sophist, understanding or philosophy is not to be confused with an inner or a priori ‘good.’ Instead it connotes success in the world. There is a very important distinction between the type of thinking advocated by Socrates and that of the Sophists: the former encourages an evaluation of one’s thoughts from the perspective of an internal uncompromising ‘good as such’; the latter identifies truth on the basis of its success or value in the material or external world.

Social Media

Whilst Socrates would have little interest in a ‘like’ button on social media, a Sophist might feel that the number of likes ascribed to a particular thought or idea is a good reflection of its inherent value, and even truth.

Socrates had little concern for the external world, which he likened to mere shadows upon the wall of a cave. He cared only that he might reconcile his existence in the world with his inner good or an internal a priori notion of truth. If that is accomplished, or at least pursued in an unbiased and philosophical manner, the affairs of society and the world will largely take care of themselves. Socrates’s ideals coincide with Confucius’s wise words:

To put the world in order, we must first put the nation in order; to put the nation in order, we must first put the family in order; to put the family in order; we must first cultivate our personal life; we must first set our hearts right.

What distinguishes Socrates from the Sophists is that the latter were practical teachers. They charged a fee, and considered knowledge a commodity. Socrates on the other hand always insisted that he had nothing to teach anyone. The wisest man is the fool, or at least he who knows the true extent of his own ignorance.

The Death of Socrates

For the Sophist, winning an argument is not simply a question of truth or falsity, but rather devolves to how the argument is presented. Using true facts to win false arguments is the criticism that is levelled against the Sophist, and indeed it is the essential meaning of the word Sophistry.

In this ancient contest we find the unacknowledged origins of advertising, and the ‘art’ of persuasion itself. Winning a false argument by using true facts, often entails convincing another of an untruth through recourse to simple self-evident facts. The other’s mind might then be hijacked into thinking and acting upon an idea that he might otherwise find repugnant. Subliminal advertising has its roots in this essential contest.

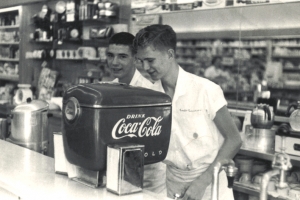

If you have been convinced by an external agency to desire popcorn or Coca-Cola at the cinema, then it is not unreasonable to assert that you have fallen prey to a certain type of invidious sophistry.

The Popcorn Experiment

By all accounts James McDonald Vicary – a late contemporary of Bernays and graduate of the University of Michigan – was an interesting ad-man. He presents a very interesting contrast to Bernays. He began his marketing career as a boy while in the employment of a company conducting a political poll for the election of a city mayor.

Sent about town in a cab, he interviewed passers-by to determine how they were going to vote. Vicary came from a humble background, having lost his father at a young age, and his family had struggled to make ends meet. A biographer informs us that his trip about the town was his ‘first time in a cab,’ and the success of his polling data in the prediction of the election outcome, confirmed his career in marketing research.

In 1957 Vicary issued a press release in which he described the results of an experiment he had conducted on the good people of Fort Lee New Jersey. The experiment is famously known as the ‘Popcorn Experiment’ and it is often referred to as the first documented use of subliminal messaging in advertising products.

Vicary claimed to have conducted his experiment on 46,599 movie goers, who, whilst watching a movie at a theatre in New Jersey, were exposed to screen images telling them to ‘eat popcorn,’ and ‘buy Coca-Cola.’ During the movie the ‘messages’ flashed on the movie screen in 1/3000th of a second, and as such were too brief to be consciously recognised by the viewers. Nevertheless, Vicary reported that these ‘subliminal messages’ resulted in a 57.5% increase in popcorn sales and an 18.1% increase in Coca-Cola sales during the movie.

Now you see it…

What is perhaps most interesting about Vicary’s story is that the experiment generated a public outcry, and was soon dismissed as a hoax or at worst a fraud. Either way, Vicary himself later declared that the results were fabricated and that the experiment never even happened.

It is important to contextualise Vicary’s renunciation. Amid the hue and cry, he was asked in an interview whether he had obtained people’s consent to have their minds ‘altered’ in the manner in which he claimed? It is quite possible, given the level of opprobrium he faced, and fearing potential claims for compensation, that he chose to distance himself from his work and quietly disappear into historical obscurity.

The irony here is that Vicary is still considered the father of subliminal messaging in advertising, and the result of the experiment was believed (or at least feared) by many to be substantially true. Indeed, there have been subsequent experiments proving the effectiveness of subliminal messaging in influencing our behaviours. The technique was quickly banned in America, and elsewhere. It seems unlikely that it would be banned if there was no possibility of effectiveness.

Although the experiment was dismissed as fraud, the unreal or ‘faked’ results convinced more people of the effectiveness of the technique than might have been convinced if Vicary’s results had been deemed truthful. Thus, ironically the faked results had an apparently greater impact in convincing people than the truth might have done. This recalls Nietzsche’s assertion that mankind is too often inclined to hold untruth in greater esteem than its inverse.

For our purposes the question is a simple one: what is the difference between the sublimation described and conducted by Vicary, and that same sublimation that was described and conducted by Bernays?

Vicary’s experiment resulted in an immediate backlash, and intervention by the U.S. Congress prohibiting such techniques. In contrast, Bernays continued to enjoy a favourable reputation and career. In the wake of his success with the ‘torches of freedom,’ he achieved legendary status within the marketing world. His books are still widely read and his techniques continue to be taught and applied.

Why is that Bernays enjoyed fame and fortune, whilst Vicary was compelled to vanish into obscurity, probably relieved that he had not ended up behind bars?

Perhaps the distinction between Bernays and Vicary’s approach, might be summarised as follows: as long as the individual subject can be preserved from the truth that they have ‘given up’ control of their mental faculties; as long as they remain convinced that the sublimated idea is compatible with their own thinking, the sublimated message will be readily accepted as an endogenous idea – one that has merely been reinforced or brought to light by the ad-man.

The Algorithm

In the wake of the 2016 American Presidential election evidenceof Cambridge Analytica meddling first came to light. It became apparent that algorithms had been applied to personal data, gathered from social media, which had then been used to manipulate voting patterns. The Western world (for a brief time) was horrified that minds had been tampered with, unbeknownst to those minds. Subliminal messaging had reared its ugly head once again.

It is highly likely, however, that the outrage was neither felt nor voiced by the true ‘victims’ of the algorithms. Rather, the anger emerged from the ‘other side.’ It was articulated, often by journalists, who felt that ‘other’ minds had been controlled, and the election of a President had been secured by devious means. This is an important distinction, and it reminds us that the victims of mind control tactics or subliminal messaging are very unlikely to admit to its effect, let alone develop an awareness of the tactics deployed on them.

Alexander Nix of Cambridge Analytica (2017).

And so it might follow that, if we, (the big ‘we’) are victims of subliminal mind control, how would we know? Who will tell us? In political parlance: only the left will inform on the right, and only the right will inform on the left. For each side of the political divide to label its antagonist as ‘brainwashed’ is nothing new. But what happens if each side is not in the habit of listening to one another, and if both sides are indeed correct?

Today we don’t have to look too far to find the evolution of sublimation: Bernay’s techniques are everywhere. Closer to home, sublimation is nowhere more obvious than in the practice of ‘predictive text,’ and the algorithms employed on social media.

When I begin to reply to an e-mail, my e-mail account offers to finish my sentences, and even offers complete sentences on my behalf. What is happening here? Why am I not insulted by a computer presuming to know my innermost thoughts, before I have taken the trouble to think them myself?

How is this process any different from what Vicary attempted in his Popcorn Experiment? Who controls this algorithm that presumes to think on my behalf? How deep into my psyche do these algorithms and advertisements reach? These are questions that we ‘victims’ rarely care about sufficiently to ask. The process appears benign and refined. Frighteningly, I cannot deny that those words the algorithm suggests do appear to coincide with what I might write, were I presumptuous enough to persist in thinking for myself!

Shouldn’t I steadfastly preserve my right to think autonomously? Perhaps I should respond like an inebriated rock star, and throw my computer screen out a hotel window in disgust at this presumptuous hijacking of my thoughts.

Tucker & the Gadfly.

I have a very close friend who does not read much. I love him dearly because he is straight and honest with me. I value his opinion because he is often more honest with me than I sometimes care to be with myself.

This friend recently introduced me to a Fox presenter whom I had never heard of called Tucker Carlson. One evening he insisted that I watch one of Carlson’s shows. Initially, I was surprised and somewhat amazed at what he had exposed me to. I forget what Carlson was talking about, but I remember being struck that he seemed quite sincere, and that much of what he was saying appeared to make sense, despite the way he was contradicting many of my core beliefs.

Tucker Carlson (2018).

Some days after watching, I decided to return to Carlson in order to better understand him, to recognise what he was trying to convince me of, and how he was going about it.

I watched two more episodes and the techniques he was employing gradually became obvious. It was not entirely clear at first, hence my perplexity and compulsion to watch him again. His techniques are no different to those used by Bernays or the sophistry of using true facts to prove false unspoken arguments. The facts were obvious, but the arguments, particularly in the arena of race, or race relations, were subtle: concealing dark convictions that align with primitive fears and aggressions.

There is a certain type of mind that is drawn to people like Carlson; a mind like my own that engages with the world with a set of hard-wired preconceptions, fears and desires. Yet Carlson was not music to my ears because I don’t harbour a fear-based love for guns or a suspicion of black people. Some of my fears I am conscious of, others less so.

If, for example, I were fearful of Black America, of its claims in respect of racism, slavery, inequality; if I were subconsciously fearful that equality or reconciliation was a threat to me; to my wealth; my morality, or my entitled share of wealth, then Carlson would be my man. It is not simply because he is racist or that he does not believe in ‘equality’. Carlson is interested in attracting an audience, and what he offers in return is a sublimated validation of one’s prejudice and fear.

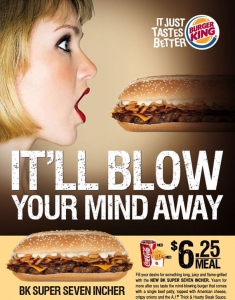

One need only watch him at work to see this. The language he uses is openly about freedom and democratic values, and yet, there is a subtext that is difficult to identify immediately, or pick out with direct quotation marks. There is an artful use of words, not quotable sentences but words, interjected into sentences, which serve precisely the same purpose as ‘Eat Popcorn’ or ‘Drink Coca-Cola.’ or ‘torches of freedom’.

One quickly gains the measure of Carlson’s deeper opinion, or at least of what would likely be his opinion upon issues like gun control, or socialist initiatives such as universal health care, race relations, capitalist wealth, or global warming.

His unspoken ‘opinions’ or sublimations in respect of race are particularly invidious. The young black American is more often portrayed as a criminal thug, a gangster, a cop-killer. Yet this criticism of Carlson cannot be sustained easily, as there are protective ‘pro-black’ images interspersed in his monologues – ordinary black folk occasionally behaving like decent white folk.

I imagine the deception is so complete that Carlson has many black subscribers. It is almost as though he is reiterating the traditional racist slur that ‘not all blacks are bad people.’ Subtle slurs like this, provide the racist with a moral foothold.

It is once again a truth that is used to prove a false argument. Undoubtedly, it is a slur that some Black Americans reiterate and perhaps unwittingly inflict upon themselves. In essence the same sentence may be seen as a subtle evolution of outright racist contempt.

The former traditional slur has a sublimated racism, whilst the latter outright form is openly vile. The former in its disguise is perhaps more invidious, the latter whilst more grotesque, is at least openly so. Carlson’s racism is in the realm of the former: the sophisticated truism that has its racism concealed beneath the surface.

But the point here is not a critique of Carlson’s techniques. Instead it is a warning to avoid the same mistake as I made. After watching two final episodes of Carlson in an attempt to gain the full sublimated picture, I then tried to get rid of him out of my life: to cleanse myself of the poison.

Unfortunately, however, my YouTube feed now regularly spits Carlson onto my screen. I only ever watched two of his shows, yet he finds me at almost every login. I often watch shows about vintage cars, van-lifers and philosophers, yet regardless of my previous choices the algorithm has decided that I am – or should become – a fan of one: Tucker Carlson, an anathema.

The algorithm has made me one of his countless millions of viewers. Perhaps I would have done less harm to the ‘greater good’ had I watched two episodes of a different kind of porn.

The modern advertisement might have been defined by Bernays, but the algorithm that finishes my sentences, sends me ‘likes’, and has wedded me to Carlson, was engineered by a small group of techies in Silicon Valley. They apply the most up to date science and research in their engineering. They reach into our minds every time we interface with social media platforms, with the Internet and the ubiquitous smartphone. The purpose of the Internet we are informed is simply to turn a profit. But what is the product they are selling, when most of these platforms appear to be ‘free’?

I have often heard it said of social media: ‘when you cannot see the product being advertised, it’s because you are the product.’

Our preferences and opinions become part of the programme, encouraging certain types of thoughts and behaviours in others. The ‘like’ button is integral to the function of social platforms and yet what purpose does it serve in respect of the data or information that is being liked or disliked? Behind the like button lies one of the core values of the algorithm itself; the Sophistic assertion that truth is dependent upon likes. That ‘truth’ becomes truer when enough people ‘like’ it.

Human behaviour is predicated upon thought: what we do and when we choose to do it; how we portray ourselves; how we are perceived by others; all of these facts become lines of code within the algorithm.

If we can assert that the history of sublimation reaches as far back as the Greek mind; what can we say of the philosophy of the algorithm? When enough thought becomes manipulated, we may well move into a world where the dominant mode of thinking becomes that of the algorithm itself.

What if the algorithm has already become our new master, the predominant mechanism for thought and the architect of empirical reality? Does it contain a few lines of code that might define or preserve a moral truth of some kind? How would we know if the algorithm is out of control, if it has ‘gone viral’?

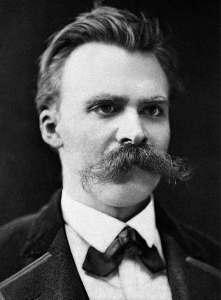

The Sophists may have had a counterbalance, a devil’s advocate in the form of Socrates the ‘old gadfly.’ Man has always had a counterbalance, a morality of some kind. If the advertisement and the algorithm have managed to move beyond morality, beyond good and evil, ‘it’ rather than we, has become what Nietzsche referred to as the ubermensch.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900)

What role does the Algorithm play in the election of a President? In taking to the streets in Dublin because a black man is murdered in America? What role does it play in hatred? In being afraid of a virus, or in wearing a face mask? In taking a vaccine, or in taking one’s own life? The darkness in our world may not be the workings of conspiracy – nor the consequence of irrational political allegiance – it might just be a consequence of sublimation: of a gullible embrace of the thoughts of others.

What has become of old Socrates, that he cannot and will not come to our rescue? Perhaps he is dead, and perhaps as Nietzsche said of God, ‘we have killed him’?

Feature Image: Alan Curtis & Patricia Morison in ‘Hitler’s Madman’ (1943).

[i] ‘Invisible Commercials and Hidden Persuaders: James M. Vicary and the Subliminal Advertising Controversy of 1957’ Kelly B. Crandall HIS 4970: Undergraduate Honors Thesis University of Florida Department of History, http://plaza.ufl.edu/cyllek/docs/KCrandall_Thesis2006.pdf

[ii] Kelly B. Crandall, Invisible Commercials and Hidden Persuaders: James M. Vicary and the Subliminal Advertising Controversy of 1957. HIS 4970: University of Florida, Department of History, April 12, 2006

[iii] Amos, Amanda, and Margaretha Haglund. “From Social Taboo to “Torch of Freedom”: the Marketing of Cigarettes to Women .” Tobacco Control 9.1 (2000). Web. 28 Apr 2010.

[iv] Bartholomew, Robert; Wessely, Simon (2002). ‘Protean nature of mass sociogenic illness’ (PDF). The British Journal of Psychiatry. 180 (4): 300–306. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/2BDC2262E104B8A33F3DD49773DA0D8B/S0007125000268578a.pdf/protean_nature_of_mass_sociogenic_illness.pdf