Are you satisfied now, ladies and gentlemen, you counsellors and therapists of all stripes, with my do-it-your-self-psychoanalysis?

Despite my disdain for the so-called misery memoir, it is time to declare: my childhood was better than being brought up in an industrial school, or by an alcoholic or physically abusive parent; but, certainly by today’s ideals, only just.

In the first of a series on his attitude to having children Des Traynor explores his upbringing and argues that being anti-natalist is not to be unnatural.https://t.co/GnTht5jurt@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @corourke91 @danieleidiniph1 @IlsaCarter1 @KevinHIpoet1967 @GarzonVico

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 1, 2021

Often, I am surprised that I even survived my upbringing, if not exactly thrived. It is an achievement, in itself, to be alive. Maybe I’m suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, after all, and have been for most of my life. Which, in turn, has led to a bad case of Imposter Syndrome. Or better still, Postnatal Depression, which cuts both ways, and is a synonym for Life.

But, as Flannery O’Connor wrote: ‘Anybody who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days.’ In the long run, you learn that parents are just people who looked after you when you couldn’t look after yourself, with whom you have very little in common – except what they put there.

‘misery on to man’

So, there you have it: I don’t have kids because I didn’t feel wanted as a child. I am just another classic example of the classical Sophoclean tale of the complexity of Oedipus, and how it wrecks. How neat, but how utterly facile – the kind of typically trite conclusion to which a therapist will always jump.

For the psychological scaring of one’s own upbringing is hardly enough to explain a lack of interest – or rather, an unwillingness to participate in procreation. After all, people with much more unsavoury childhood experiences than I still manage to produce children of their own. That’s part of the recurring cycle of man passing ‘misery on to man’, in Larkin’s phrase, from the one poem of his which everyone can quote from memory.

It is what he means by ‘Still going on, all of it, still going on!’ to quote from another, less anthologised of his works. No doubt the mind-doctors will predictably claim that I am merely in denial here about the effects of my formative childhood experiences on my psyche. But denial is such a difficult concept to prove in practice. Not that I reject outright the idea that there may be some residual influence – how could there not be? My parents may well have given me ‘all the faults they had’ and added some more, just for me. But does that inevitably make me, in the words of a fictional Larkin biographer from another of his more well-known poems, ‘One of those old-type natural fouled-up guys’, the sort who notoriously cautions ‘Don’t have any kids yourself’? Hardly – anyone who knows me will attest to my lively sense of humour.

Ah, but maybe I’m just trying to cover something up with a jokey, rock’n’roll exterior? Ah, but aren’t we all – with whatever masks work best for us? We all ‘prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet’, like poor old Prufrock.

In the end, your relationship with your parents, and your perspective on your childhood, is a bit like your relationship with and perspective on the place where you were born and grew up, or even with your country: some people become expatriates; some people stay close to home; and some people are at peace with whichever arrangement, and some are not.

One can treat that relationship with as much seriousness or triviality as one likes, although for many professional mental healthcare workers, it will always be serious. In any case, this excavational writing project I am engaged upon vouchsafes that I am not in denial: I have acknowledged the debt the past has burdened me with; what you are reading can be construed as my effort to (clears throat) ‘move on’.

Sinatra Family, 1949.

It’s Parents

(Joke: It’s not the mother and father I blame: it’s the parents.) Except, for me, it’s more a case of

‘It’s not children I don’t like: it’s parents.’ For here’s the thing: for someone who appreciates, if not quite advocates, childlessness, I quite like children. Obviously, one cannot generalise about all children, as individual children can differ from one another almost as much as adults do. But, in general, I prefer the company of most children to that of most adults.

This has something to do with the hope projected on to them: they haven’t quite been beaten down and made bitter by life experience, yet. If there is hope, it lies in the children. But there is no hope, because of the parents. Little people have usually regarded me quizzically, probably because they perceive me to be unlike most other adults in their lives. I can usually speak to them on their own level. I am not an authority figure.

You can learn a lot from children about looking at the world in an original way, if you listen to them, which so few adults do. But I like being able to give them back to their biological parents, when the fun is over. I only want the good parts. (Joke: I like children, but I couldn’t eat a whole one.)

Fortunately, this seems to suit most parents, who are only too glad to have their children taken off their hands for a while. I’m thinking of all those poor little rich kids, from all over the place but especially the progeny of Russian oligarchs, whom I taught (i.e. babysat) on summer courses over the years. All the neglected boys could do was play computer games; all the neglected girls could do was go shopping. Of course, they are the issue of the class of people who view having children as a lifestyle choice rather than as a luxury.

Parents may lavish fortunes on the education of their children, but they actively seek to avoid spending too much time with them. Just as children may look forward to hefty inheritances, but are quite prepared to deposit their parents in residential care homes while they are waiting for their windfall, rather than look after them at home themselves. Family values, eh?

The 1937 Irish Constitution.

The Family

‘It’s not children I don’t like: it’s parents.’ Which means, of course, that what I really don’t like are families, or rather, the fetishisation of ‘The Family’ as an abstract concept, as for example in monotheistic religions, or in Bunreacht na hÉireann, the Constitution of Ireland. (Article 41.1.1. ‘The State recognises the Family as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society, and as a moral institution possessing inalienable and imprescriptible rights, antecedent and superior to all positive law.’ Article 41.1.2.

‘The State, therefore, guarantees to protect the Family in its constitution and authority, as the necessary basis of social order and as indispensable to the welfare of the Nation and the State.’ Okay, so. But what about all the citizens who, for whatever reason, have never lived in families, and/or never will live in families – unadopted or unfostered orphans, for a start, or Catholic clergy?) And I reserve a particularly virulent animus against ‘The Good Family’, as in “He/She is from A Good Family” or from “Good Stock” or “Decent People”, ‘good’ and ‘decent’ here invariably meaning church-going, law-abiding, well-connected, prosperous middle-class, and ‘respectable’ – except most of them are not.

Thus, the origin of the phrases ‘The black sheep of the family’, and ‘Disgracing the family name.’ If I had a fiver for every time I’ve been to a job interview – and even in supposedly liberal operations like newspapers or publishing houses – and been asked “Who are your family?’ or “What is your father doing now?”, I’d have a tidy sum squirrelled away. “Where do you stand on the church?” was also an old favourite when trying to land a teaching job, as recently as the late 1980s.

Needless to say, the potential employers were not overly impressed with my answers. If it were not for hereditary privilege, many monsters (themselves the offspring of monsters) throughout history would not have got within even an ass’s roar of power. Just think: wouldn’t the world be a better place without contemporary manifestations of the phenomenon, such as Lochlan Murdoch or Ivanka Trump, having easy access to global media and political influence?

Prashant Shrestha from Kathmandu, Nepal.

The Dialectic of Sex

Before you peremptorily dismiss me as a crackpot, please hear me out, for I am not a lone voice crying in the wilderness in this predilection. In The Dialectic of Sex (1970), second wave feminist Shulamith Firestone criticised the nuclear family as a construct, arguing that it not only limits women’s independence, but inhibits child development too. In her view, children are hindered in their abilities to develop because of their education, predetermined positions in the social hierarchy, and ‘lesser importance’ in comparison to their parents and other adult figures in their lives, who control all these aspects of the children’s lives. She believed that nuclear families, as a form of social organisation, creates inequality within a family, as the children are considered subordinates to their parents.

This, in turn, has increased maternal expectations and obligations, which is something Firestone thought society should outgrow. This dependency on maternal figures makes the child(ren) more susceptible to physical abuse and deprives them of the opportunity to work towards being independent themselves, economically, emotionally and sexually. She sought to solve these problems by eliminating families for the raising of children, and instead to have them raised by a collective.

William S. Burroughs also advocated for the disintegration of the family unit, most vociferously in The Job: Interviews with William S. Burroughs by Daniel Odier (1989), since he believed it to be redundant.

Jean Genet wrote in The Thief’s Journal (1949): ‘In my opinion, the family is probably the first criminal cell, and the most criminal.’ ‘Ah, but those guys were queer’, I hear members of the right-wing Christian fraternity proclaim, ‘so what else would you expect from them?’

Alright, let’s enlist some good, straight, honest Irishmen as well. Poet Dennis O’Driscoll wrote that ‘Every family has passed its own version of the Official Secrets Act’, and doubtless with good reason.

Time and again in his work, Samuel Beckett targets parents as irresponsible criminals, by dint of their bringing more life into this sordid and corrupt world, and thus creating families. ‘You’re on earth, there’s no cure for that,’ says Hamm to Clov in Endgame, and addresses his father Nagg as ‘accursed progenitor’. Indeed, Beckett could easily be construed as a proto-supporter of women’s reproductive rights, as the narrator of First Love is horrified when his lover Lulu/Anna reveals that she is pregnant: ‘Abort! Abort!’ he says, adding, ‘If it’s lepping, I said, it’s not mine.’

Furthermore, for Stephen Dedalus in the ‘Scylla and Charybdis’ episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses (even if it can be configured, as Hugh Kenner chooses to do in Joyce’s Dublin, as callow – in contrast with Leopold Bloom’s mooted fatherly maturity), ‘Paternity is a legal fiction’ (or, as my own father used to put it more plainly: “There’s manys the man rocks another man’s child when he thinks he rocks his own.”).

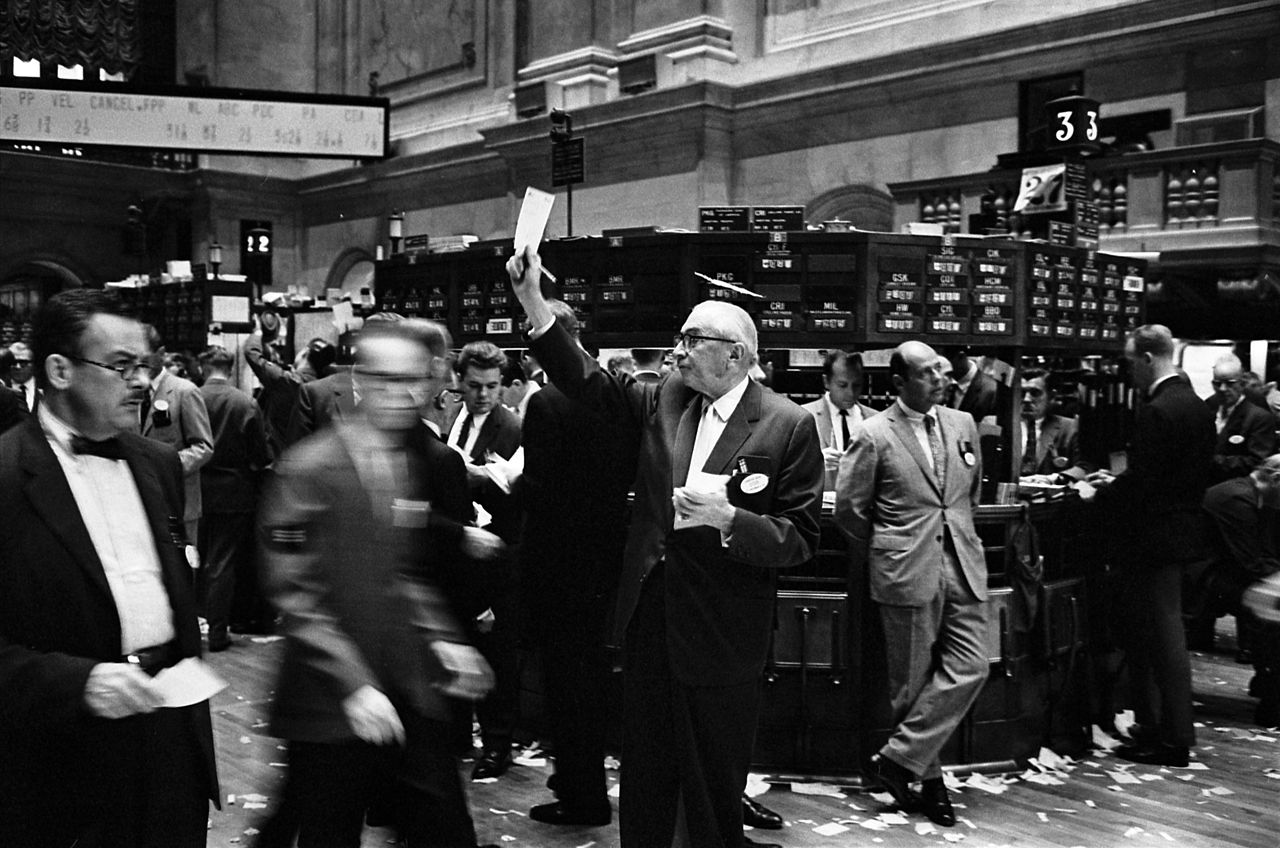

Stockbrokers, New York, 1966 from United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ppmsca.03199.

Wealth Accumulation

It can easily be argued that marriage, monogamy and parenthood exist primarily to foster and protect property and inheritance, and to encourage wealth accumulation. These arrangements sponsor and attempt to justify the greed and acquisitiveness of rampant laissez-faire capitalism, since parents can always claim that they are not acting disreputably out of their own selfish interests, but rather are indulging in seemingly self-serving and nakedly avaricious behaviour merely for the good of their offspring, by endeavouring to give them the best start in life and ultimately securing their future.

Thus the casting of family formation as somehow having a Stake in Life, or in Progress, or in The Future, or some such nebulous notion. But would people really be so competitive economically, to the detriment of others, if their children were raised communally, and all the children of the nation were really cherished equally – i.e. have exactly the same resources available to them?

This alternative method of social organisation would certainly give the lie to the oft-repeated right-wing mantra that free market capitalism is a meritocracy – where the harder you work, the more you are rewarded – because all children would be starting life on precisely the same footing. After all, ‘It takes a village’, as even prominent neo-liberals like to tell us.

Besides which, is the family really such a Haven in a Heartless World, as historian Christopher Lasch had it, in his 1977 tome of that title? Lasch traced over a century’s worth of sociological and psychological theories on the contemporary family, situating his observations in the context of expanding social institutions and their besieging of the family’s power and influence, and taking issue with most of them.

However, while Pope John Paul II may have opined that ‘as the family goes, so goes the nation, and so goes the whole world in which we live’, surely if the family is a microcosmic unit within the macrocosm of society itself, then the overall health of the family should be a good indicator of the overall health of the culture at large. If the world is indeed heartless, then perhaps the first place in need of reformation is, in fact, the family. In this alternative cosmology, friends may well be God’s apology for family since, unlike your family, you get to choose your friends.

There is at least as much evidence to suggest that, far from being a haven, families can just as equally be claustrophobic minefields of unbearable tension and resentment. From the patricides, matricides and fratricides of Greek tragedy, to a headline ripped at random from yesterday’s newspaper: ‘Domestic violence by adult children against parents rises as stress peaks under lockdown’, this assertion is incontestable. A recent statement from the Garda Commissioner informed us that domestic violence claims more lives in Ireland every year than gangland crime.

Of course, you can counter-argue that these kinds of pressures on family life are direct consequences of consumer capitalism (adult kids can’t afford to rent, much less buy, which is why they are living at home), but the fact remains that the concept of the happy and supportive family is an aspirational mirage, with little tangible substance: some parents may get on with each other, but many don’t; some parents may get on with their children, but many don’t; some siblings may get on with each other, but many don’t; some children may get on with their parents, but many don’t; some families may work, but many don’t; some may work at different times, but not at others.

Greta Garbo as Anna Karenina.

All Families are Alike

Here we can invoke Tolstoy’s famous opening line of Anna Karenina: ‘All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ But are all happy families really alike? Perhaps their happiness is just as idiosyncratic as the unhappiness of the unhappy. In addition to which, I can’t help but ascribe a degree of conscious irony to Tolstoy’s declaration. After all, we do not encounter any ideally happy families in Anna Karenina. Perhaps he knew, as well as anyone, that the Happy Family is a myth, an ideal to which we may aspire, while having no palpable earthly iteration. But whenever Family Values types start pushing The Family ‘as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society’ at me (unfortunate enough as that phrase is in its easy slide into Margaret Thatcher’s infamous claim that ‘…there’s no such thing as society.

There are individual men and women and there are families’), I usually refer them to the Christmas dinner scene in Joyce’s A Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man, which is, if nothing else, a needful corrective to the sentimental ghosts of Dickens, and bolsters Wilde’s epigram to the effect that ‘Sentimentality is merely the bank holiday [e.g. Dickens’ Christmas] of cynicism’. For, despite the episode’s grounding in personal autobiography and the particular politico-religious strife among nationalists in Ireland at the time, the reason for this Yuletide row’s universal appeal is that Joyce wasn’t just writing about his own family: rather, he was writing about everyone’s family, in every time and place.

There is always something to argue about, and it hurts more to argue with relatives who espouse views diametrically opposed to your own than it does with anyone else. Or will you just sit there and bite your tongue for the rest of your life?

At any rate, however positive or negative your view of family life, I have no particular desire to be part of the hurdy-gurdy of what a friend calls, speaking of his own familial ups and downs, ‘the great human dance’. Or, at least, his version of family dancing and enforced role-playing. I am more partial to jitterbugging than waltzing, to doing the watusi than executing a quadrille.

Image: Richard Tilbrook (wikicommons)

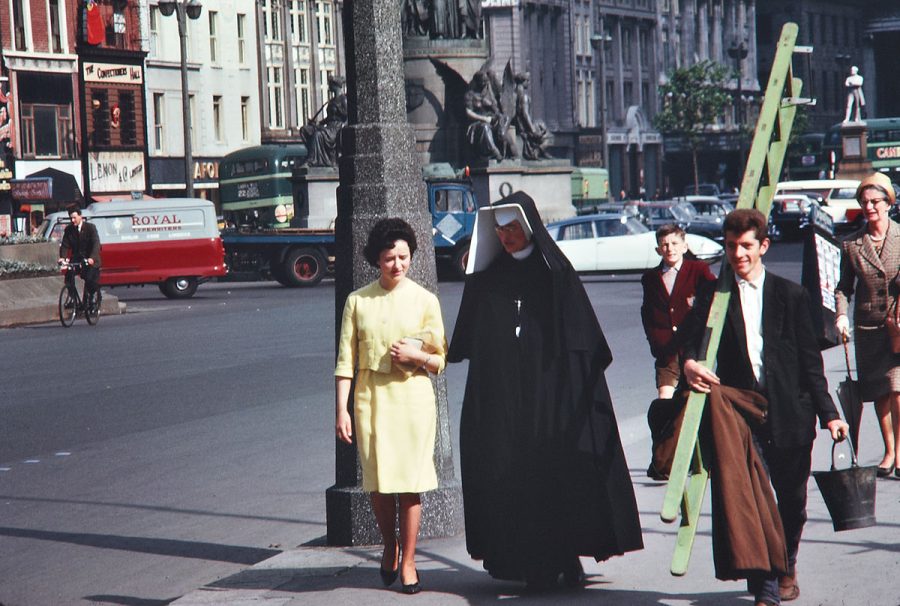

Irish Social History

These considerations take on a particularly lurid hue in the light of 20th century Irish social history, especially when juxtaposed with the aspirational ‘official version’ rhetoric which is still regularly trotted out around the Irish family (see Articles Article 41.1.1. and Article 41.1.2. of Bunreacht na hÉireann, above).

The record of incarceration and institutionalisation of Irish citizens in Mother and Baby Homes, Magdalen Laundries, Industrial Schools and Psychiatric Hospitals is grim, and involved the blatant rejection of children and grandchildren by their parents, siblings and extended families, in the name of a church-and-state-sponsored ‘respectability’ based on the notion of ‘legitimacy’. These wounds are still raw in many peoples’ memories. As a younger acquaintance recently put it to me: “I was born in 1993 to a single mother who raised me. The last Mother and Baby Home in Ireland closed in 1998. It could have been us.”

Therefore, I salute the scholarly tenacity of both Clair Wills, in her article Architectures of Containment (London Review of Books, Vol. 43 No. 10 · 20 May 2021), and Catriona Crowe, in her piece The Commission and the Survivors (Dublin Review, #83, Summer 2021), for their persistence in wading through 2865 pages of what is essentially obfuscating, buck-passing apologetics contained within the Final Report of the Commission of Investigation into the Mother and Baby Homes (Government of Ireland, October 2020), and their deep excavation and dismantling of it.

Wills refers to the ‘inalienable family logic’ of the system, and speculates that: ‘Arguably the rhetoric of the Irish family was a smokescreen for the absence of the family as a private sphere of emotional and affective ties’, declaring that ‘the Irish church and state, with the passive acceptance and sometimes active collusion of Irish families, was willing to sacrifice its own children – of whatever age – for what it considered to be survival.’ Crowe comments: ‘One has no right to expect dazzling prose in such a document, but it is striking how badly written, argued and organised the commission’s report is. The tone is at times hectoring, at times defensive, at times cryptic – and sometimes all three…’ The cover-up continues…

While some may read more recent progress in Irish social legislation – such as the legalisation of same-sex marriage and the repeal of the eighth amendment – as forms of ‘respectability politics’, they at least demonstrably signal significant shifts in attitudes as to what constitutes concepts of the Irish Family, moving on from a theocratic patriarchy to a broader and looser inclusivity.

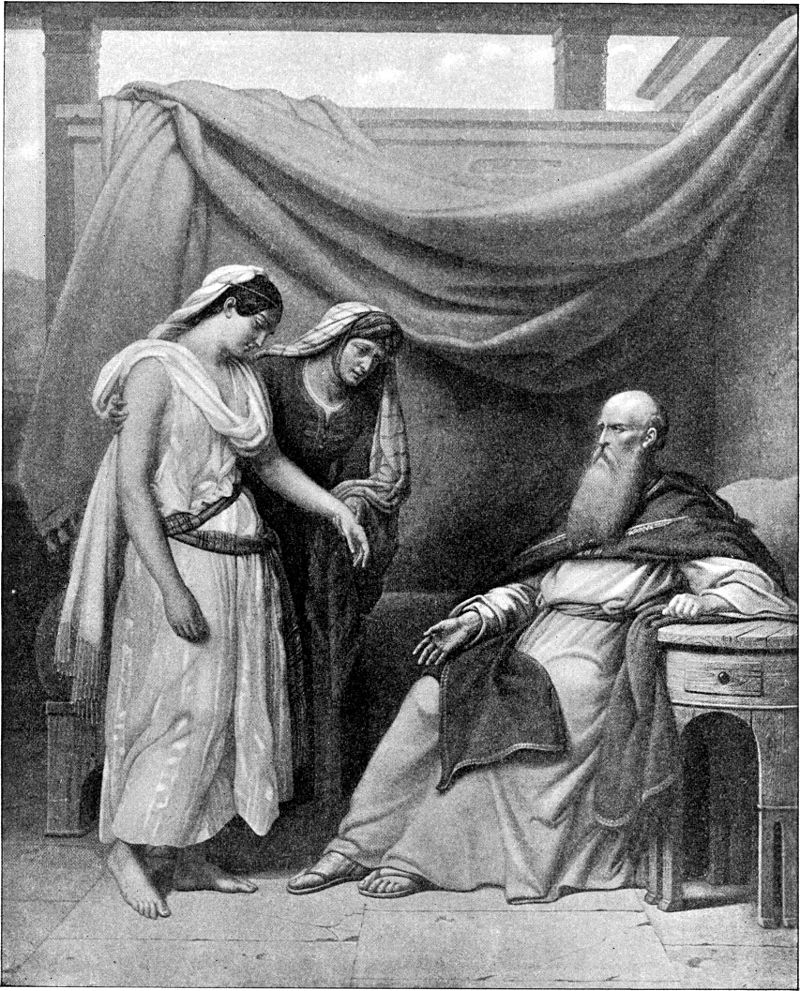

Abraham, Sarah and Hagar, imagined here in a Bible illustration from 1897.

Patriarchy

‘Which means, of course, that what I really don’t like are families…’. Which means, of course, that what I really don’t like is patriarchy. Men can be victims of patriarchy, just as much as women. (Although, even if they aren’t, they should still dislike it, out of solidarity with their womenfolk.) I myself have suffered my whole life at the hands of all manner of male authority figures (e.g. priests and Christian Brothers to whom my parents deferred, and so who consequently had inordinate control over my formative years; teachers too interested in favouring students with more upwardly-mobile parents than mine to pay attention to me; doctors and surgeons who would not admit mistakes when they treated me, when it was obvious mistakes had been made; potential employers who found my performances at interviews too idiosyncratic to countenance employing me, despite abundant relevant qualifications and experience).

Bumptious, self-important fools. I could never imagine myself in the role of a patriarch, or even a more benign paterfamilias. Hence, perhaps, another reason why I don’t have children. Not that I hold much brief for matriarchy either – which, curiously, has markedly strong manifestations in Ireland: just look at the ubiquity of mariolatry imagery.

I myself have suffered my whole life at the hands of all manner of female authority figures (e.g. women in many of the same roles as the men already listed – proving, paradoxically, that equality isn’t always an unalloyed ‘good thing’). Brash, conceited harridans. I could never imagine putting someone in the role of a matriarch, or even a more benign materfamilias.

Hence, perhaps, another reason why I didn’t want to give a woman a child. So maybe it’s not so much patriarchy (etymology: ‘from patriarkhēs “male chief or head of a family” ’) or matriarchy (etymology: ‘government by a mother or mothers; form of social organization in which the mother is the head of the family and the descendants are reckoned through the maternal side”, formed in English 1881 from matriarch + -y and “patterned after patriarchy”) that I dislike, as ‘archy’ itself (etymology: ‘word-forming element meaning “rule”, from Latin -archia, from Greek -arkhia “rule”, from arkhos “leader, chief, ruler”, from arkhē “beginning, origin, first place”, verbal noun of arkhein “to be the first”, hence “to begin” and “to rule”.’)

As a good ex-punk (is there really any such thing as an ‘ex’ punk? – no, of course not, old punks never die, they just sign to CBS, and/or get into country music), perhaps the only -archy I like is an- (from Greek, ‘without’) -archy. All rules are arbitrary. They are mutually agreed conventions, employed for as long as those with power consider them useful, until they are convinced otherwise, or in advance of them losing power. As with the power of parents to rule the lives of their children.

Meet the Parents

It is plain to see that parents get a bad press, in both popular culture and theoretical discourse. From ‘Mom jeans’ to ‘Dad rock’, from Meet The Parents (and The Fockers) to The Happiest Season, parents are presented as embarrassingly and quintessentially naff. Parental units are decidedly unerotic, and are easy targets for comedic caricature. Sometimes they bring it on themselves: consider Parental Advisory Explicit Content stickers on album covers.

No offspring wants to sit watching grown-up films or television series with their ‘Old Pair’, or even share their musical tastes and latest tunes with them. Picture Sherilyn Fenn’s iconic small screen epiphany as Audrey Horne in the first season of David Lynch’s seminal series Twin Peaks (1990), where during a job interview at One Eyed Jacks she knots a cherry stem with her talented tongue, and the large cringe factor of your Old Dear piping up from her rocking chair, perplexedly, “What does it mean?” (Mind you, it wasn’t just the Mother; the Sister dissed the show after seeing Audrey swaying around the Double R Diner to Angelo Badalamenti’s theme music “Like she was on drugs”.)

Hands up if you can remember being told to “Turn that racket down” while losing yourself in the latest punk masterpiece (e.g. The Clash’s eponymous debut album). I even have a more precise memory of ma mère’s shocked chagrin on overhearing the line ‘By the devil’s holy water and the rosary beads’ in The Radiators’ classic ‘Song of the Faithful Departed’, from Ghosttown (1979) – a song “mocking God”. ‘Who were your parents?’ and ‘What was your childhood like?” are the first questions any self-respecting and well-trained psychotherapist is going to ask you in a consultation (€50+ an hour, and they’re fifty-minute hours too), and we all know where the blame for your troubles and woes, your utter fucked-upness, is going to lie.

Personally, I struggle to listen to any opinion being expressed when it is prefaced by the age-old, ingratiating formula “Speaking as a parent…”. Is there any more grating conversation-stopper, guaranteed to shut down any debate, than “You’d understand if you had kids”? “I have kids to support” is used as an excuse by parents for every unenviable life choice they make, from staying in an insalubrious work situation (“My boss is such a bully”) to, worse, staying in a bad marriage (“Not in front of the children”). For the majority of parents, their children represent hostages to fortune.

Bonkers Parenting

Literature furnishes plentiful examples of misguidedly inadequate or blatantly bonkers parenting. Passing over the treatment of daughters by their parents – usually their mothers – in the fictions of Jane Austen, I could also cite Mrs. Kearney in James Joyce’s short story ‘A Mother’, who mortifies her daughter Kathleen, an aspiring pianist, by sweeping her out of a concert hall and irritating the promoters and other artists, with her impatience to get paid immediately for Kathleen’s contribution to a recital series, thus ruining her career in Dublin musical circles.

But I’m thinking specifically and more contemporaneously of Donald Barthelme’s very short short story, ‘The Baby’, a succinct satire on the arbitrariness of parental discipline and punishment.

My wife said that maybe we were being too rigid and that the baby was losing weight. But I pointed out to her that the baby had a long life to live and had to live in a world with others, had to live in a world where there were many, many rules, and if you couldn’t learn to play by the rules you were going to be left out in the cold with no character, shunned and ostracized by everyone,

reasons the father of a fifteen-month-old baby girl, sentenced to spend four hours alone in her room for every page she tears out of books. ‘We had more or less of an ethical crisis on our hands.’

To be fair, fiction is also replete, from a parent’s perspective, with skewering specimens of outrageously uncontrollable children. I’m thinking here of the monstrous Marmaduke, the ten-month-old toddler from Martin Amis’ London Fields (1989), an infant his parents agonised over bringing into the world, given its less than perfect state, who then turns out to terrorise their lives like a violent dictator. But perhaps the most equanimous artistic depiction of parents’ burdensome redundancy to their busy children is Yasujirō Ozu’s unbearably moving Tokyo Story (1953), a masterpiece of such universal resonance that it regularly tops polls as one of the greatest films ever made. Do you seriously believe your parental journey will be significantly different from any of the examples highlighted above?

Some people get to resolve their differences with their parents, usually as they move into middle age and take on the trials and tribulations of parenthood themselves. This will not happen for me. My father died when I was thirty-three; my mother died when I was forty-one. They were both six foot under, and I had failed to produce an heir, to add to their already numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren. They are united now at last in death, for ever, as they never were in life, decaying together in Deansgrange Cemetery, in the wet, mulchy earth, underground.

More than Enough

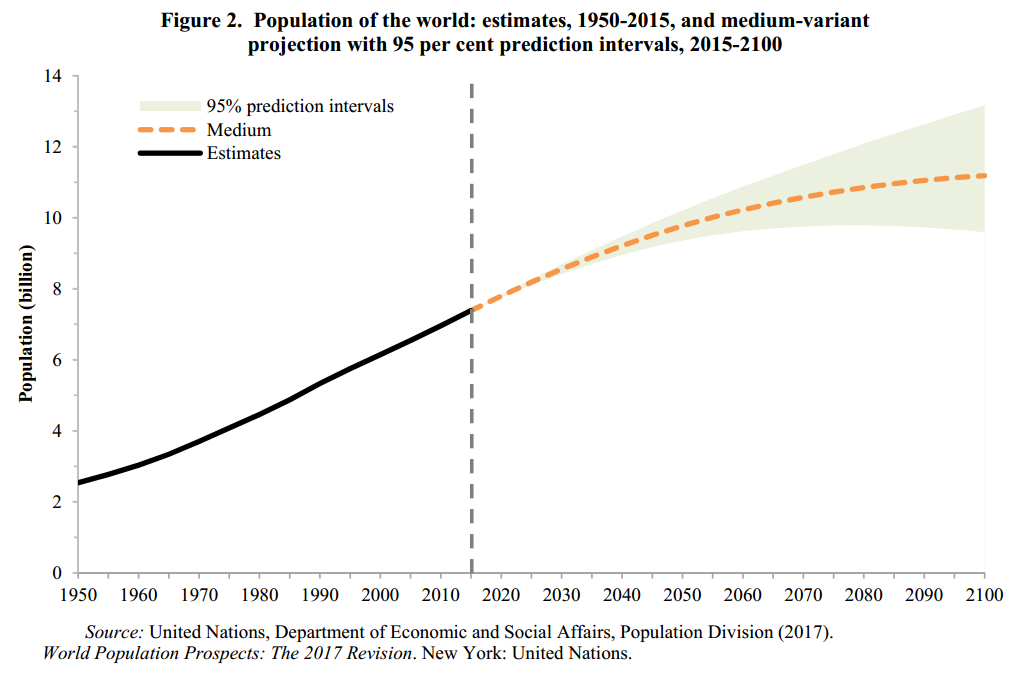

To look at the broader picture, and to echo some anti-natalist arguments: there are more than enough people in the world. (Roughly 8 billion, give or take a few hundred thousand, and rising by – at a conservative estimate – at least 1 per cent annually: that’s 80 million a year, in plain language. Visit www.worldometers.info for impressive minute by minute stats. There is way more than one born every minute.)

What kind of bloated egotism does it take to believe that your priceless strands of DNA are going to make any difference whatsoever to anyone other than yourself and/or your partner, much less make that world a better place? Particularly when the species isn’t exactly in imminent danger of completely dying out anytime soon.

In fact, on the contrary, more people are more likely to hasten the demise of humanity’s living space, Planet Earth, through the devastation that overpopulation brings. To those who would admonish me to the effect that my child freedom is merely an unwillingness to shoulder adult responsibility, I say: in all likelihood I am more responsible than you, by not having any children. To say nothing of the fact that there are huge swathes of people who, for a variety of reasons, have great difficulty or ultimately find it impossible to reproduce.

Both LGBTQ+ couples and heterosexual couples with fertility issues are required to take circuitous and sometimes difficult routes into parenthood, either through assisted reproductive technologies like IVF and donor insemination, (which detractors would call ‘unnatural’, and which is why, of course, they are considered such an abomination by the Godly ‘pro-lifers’), or via other complicated arrangements such as surrogacy, co-parenting, adoption or fostering.

Then there is the childcare issue. Despite the good intentions of the aforementioned Constitution (Article 41.2.1. ‘In particular, the State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.’ – itself the subject of much controversy and contentiously archaic because of its gender specificity), Irish society has organised itself over the years into the current shambles whereby, under the influence of Anglo-American neo-liberalism rather than European social democracy, both members of a couple are required to work to maintain a roof over their and their potential or actual offsprings’ heads, which in turn means they are required to stump up exorbitant fees for private creches to look after said offspring while they are out slaving to provide food and shelter for them. (So much for Article 42.1.2. of The Constitution: ‘The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.’)

Does that seem like a fair deal? So, essentially, unless you have other family members (usually grandparents) or friends willing to take them off your hands for the best part of the day, or you move to a mainland European country with proper public services, you are snookered.

The professional classes, i.e. those in the best position to exploit and therefore gain most from the present system, solve this conundrum by availing themselves of au pairs, or by hiring and underpaying Filipino nannies. Here, as with so much else, they ‘go private’ – doubtlessly believing that this is the natural order of things. Here, as elsewhere, my hardwired class antagonism – which some will doubtlessly dismiss as merely ‘a chip on his shoulder’ – burns brightly.

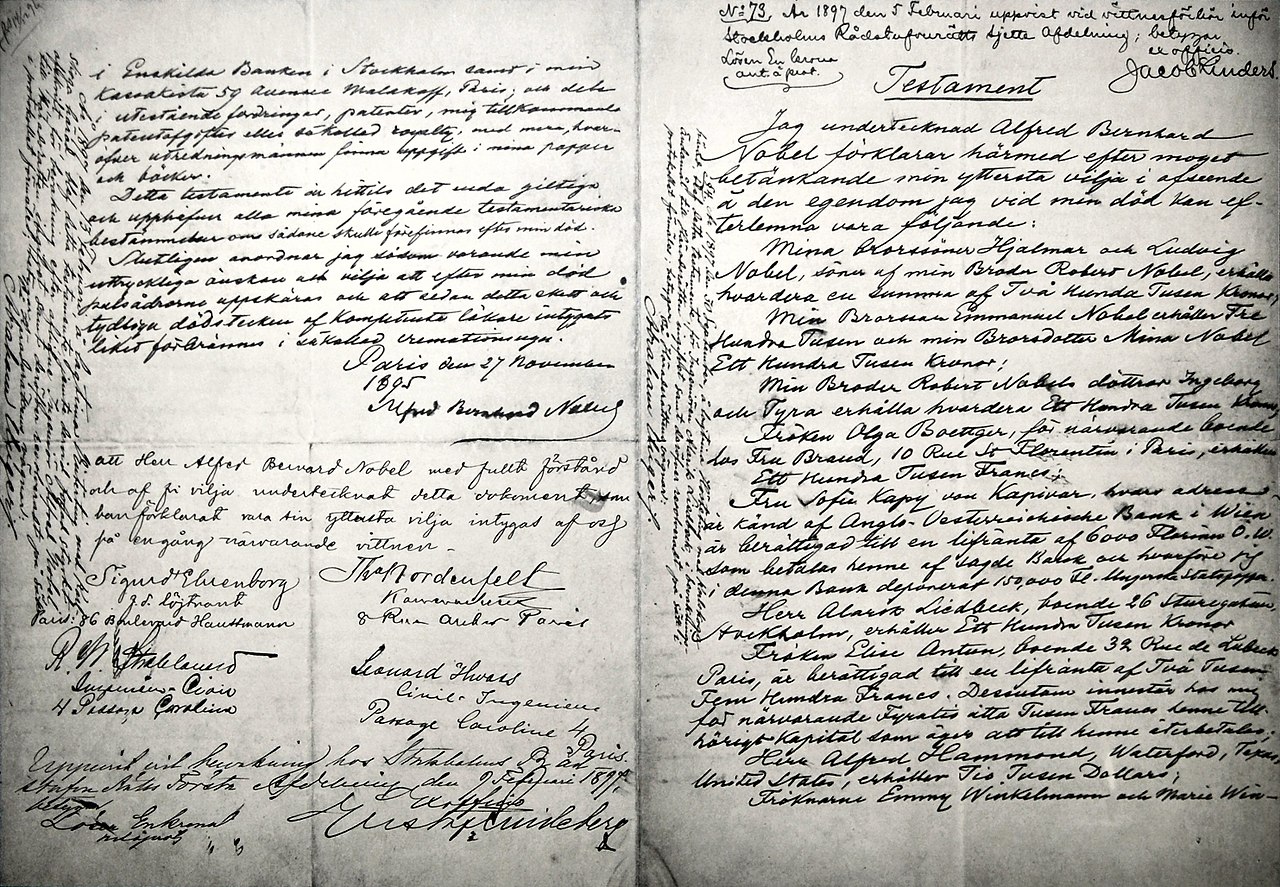

Alfred Nobel’s will.

Legacy Issue

Then there is the legacy issue. If you happen to have done well for yourself, whom do you leave your fortune to? In that case, having some blood heirs might be a good idea – although as previously mentioned, perhaps you have only done well for yourself because you had heirs in the first place. And what of those, the majority, on average incomes, or the poor, who have amassed little or no capital to pass on to their sons and daughters – many of whom, in any case, may be just waiting around for parents to pass on so that they can get their greedy paws on what loot there is? Many people still have children as a form of long-term investment, because they think their offspring will contribute to the household budget – although these days parents are more likely to get stuck for stumping up deposits for their first time buyer children’s houses (in Ireland, we actually have an ex-Taoiseach (Prime Minister) and current Tánaiste (Deputy Prime Minister), who recommended in the Dáil (Parliament) that young people go to “The Bank of Mum and Dad” as just such a method of securing a mortgage); or because they think their flesh and blood will be a comfort to them in their old age, or at least look after them in their declining years and decrepitude – when in reality they are more likely to be packed off to a care home, so that the ungrateful fruit of their loins can get on with their own mid-life lives.

In fairness, given the lack of state services for elder care as well as child care (described above) under the present dispensation, and the inter-generational disparity in access to property ownership, the overworked adult children and parents often have no other choice but to outsource caring roles for family members younger and older than themselves, which were traditionally performed by family members.

Thus, privatisation begets more privatisation, and neo-liberal capitalism actually works to the detriment of The Family, or, more accurately, non-affluent families, which it ostensibly trumpets upholding.

Americanization of California (1932) by Dean Cornwell

Enlightened Self-Interest

In any case, the inheritance question is not one that applies much to me personally, either as recipient or as donor, because amassing a nest egg to make life easier for his litter was not high on my father’s or mother’s list of concerns.

“There are no pockets in the last suit,” quoth he, perhaps hoping to imbue me with the same fatalistic attitude. I dare say he succeeded. He clearly had no ambitions towards founding a dynasty, at least not one based on the accumulation of financial wealth and economic power. His plans for his bloodline probably extended no further than ‘put them on the right road’ and ‘let them find their own way’, with the Catholic religion, the ‘one true church’, as their guide.

Naturally, if I were the progeny of a wealthier or landed lineage, perhaps my analysis of inherited wealth would be entirely other. With notable exceptions, altruistic or aspirational, most people tend to espouse the socio-political philosophies and policies which are best tailored to the fullness or emptiness of their own pockets, rather than worrying about an ill-defined ‘greater good’. ‘Enlightened self-interest’, I believe it’s called.

Who knows, what a great Fine Gael/Tory/Republican Party fascistic scumbag I would have made, and what horrors I could have perpetrated, if only I had had a family fortune to protect and grow.

Given these considerations, probably the only truly selfless and ethical way of having children and creating a family is by adoption. At least you are caring for already born orphaned or abandoned kids, whose own parents could not or would not look after them. Failing that, get a dog or a cat.