I’ve just made my last film, a short called Bog Graffiti. Another last film.

I always make that resolution when a film is put to bed. Never again, I say, will I go through the pain.

In my childhood the cinema was already a fantasy, one which we could only occasionally afford.

When as day trippers we went on excursions to Bray, one of the novelties was a machine with a handle. If you inserted a penny – a large investment – you could wind the handle and view a jerky series of photos which constituted a thirty-second epic of what the butler saw. The technique was analogous to that of Edison fifty years before, when he filmed a five-second sneeze.

Though moving images are what have been laughingly called my livelihood for too long, the medium was never my first love. I merely stumbled into it, an accidental activity that seemed to fit me like a glove, rather like a loyal and unappreciated wife.

I am no longer considered by apparatchiks to possess the puff to make another, but I can still enjoy the rare film of excellence made by somebody else and, if provoked, become long-winded about the process of becoming a film maker.

There are two accepted routes. The first is the apprenticeship method: you watch and listen to other people doing it. The second is through formal media courses which produce experts rather than film makers. Neither of these processes has much to do with actually making a film – it largely depends on not being very good at anything else. The same principle applies to most art forms: they are not a matter of loving or wanting, but about desperation. You either have to do it or you do not. I needed it, or at least something like it. Film would do for what is referred to ‘as the time being’ – a period which in my case extended to a half-century.

My first short film took as its theme Eliot’s, ‘The Love Song of Alfred J. Prufrock’. It featured a middle-aged actor paddling in the sea, listening for the mermaids while his withered wife lay on Killiney beach, settling the pillows by her head and murmuring about Michelangelo. At least that was what I hoped to imply. Surefire box-office. Six of us RTE trainees had spent a few months listening to two Danish film experts. First they showed high-class documentaries. Secondly they loaned each of us a 16mm camera for a day. I went into the city and filmed shadows. I was hooked: it wasn’t like work at all.

My early attempts have been lost in the bowels of RTÉ. In those early days, the concept of posterity did not exist. Nobody was going to die. Until Seán Ó Riada did, aged forty.

It is not easy, in this impenetrably complex era of digital reality, to re-imagine what film-making once involved. Principally, film was a chemical, rather than the electronic process which now dominates the activity. The former meant controlling a light source (usually daylight) so that it would disturb the silver nitrate particles on sensitised celluloid in such a precise fashion as to produce a desired image.

Whether it was 16mm gauge film, which was the TV standard in those days, or 35mm which was the cinema standard, there were twenty-four of those images exposed per second. In between, each of those images was a fraction of a second of black whose quickness of passing deceived the eye so that it was not noticed.

Next, the same celluloid had to be treated in chemical baths to remove the silver and reveal the negative images. It was rumoured that film laboratories in England made more profit from the recycling of silver than from the processing fees they charged.

The late and much-travelled Barney McKenna, banjo player in The Dubliners, once confided to me his advanced ideas on the subject. He said that the Rhine was so polluted with chemicals flowing down from Switzerland that the film industry didn’t need laboratories. German film makers simply dipped their films in the chemical stream. That’s how Germans could make films cheaper, Barney said.

At our basic level the director and cameraman had to work without a picture monitor. Using the tiny camera viewfinder and a light meter, the framing and exposure of the picture had to be imagined beforehand. The resultant images could not properly be seen until they were processed and returned from the London laboratory as ‘rushes’.

Nowadays there are LCD viewfinders on video cameras, which allow you to see precisely what the lens is producing. If you still don’t know what you are doing or can’t make up your mind, that is no obstacle. Videotape, mini-cards and something called cloud technology now mean that you can cover your vacillations by shooting endless hours and unlimited ‘takes’ of the same scene. You can rely on the editor to spend hours and days selecting the most appropriate shots from the chaos. That is why film editors develop a nice line in profanity and why post-production costs escalate.

Previously the director had to describe the shot and movement he wanted. The cameraman had to interpret this wishful thinking and, sighing, mark the lens barrel with slivers of white camera tape to remember his different points of focus. Nothing was automatic. He had to meter the available light and adjust the lens accordingly. All these matters had to be addressed after the important creative decisions were made: what was the purpose of the shot, what should the actors say and do, how much film stock and daylight are left, how can the sound man pick up dialogue without revealing the microphone but, principally, what time is coffee break?

The process was tangible, especially the editing which was done by physically manhandling the film on a Steenbeck machine and winding the magnetic soundtrack backward and forward to acquire synchronisation of sound. The latter required, at the beginning or end of each take, a distinct noise in precise coordination with an image of that sound’s source. This requirement was usually met with the clapperboard. Sometimes you just clapped your hands in front of the lens.

It was not just a rumour that the late Fr Joe Dunne, intrepid Radharc oneman film crew, solved this problem in non-unionised foreign parts with his shoe. He would start the camera (a Pro 1200 monster which I inherited from him) and focus on an interviewee, then take off one shoe and fling it at the visible wall behind the subject – which might easily have been a flinching Archbishop or a South American dictator, for all Joe Dunne cared. All human beings were accorded equal respect by him, and his primitive technology worked, according to his talented editor Dáibhi Doran.

As film stock and processing were expensive, the ratio of exposed film to the final product was at most 4:1 and even that, I remember, was extravagant. To save money, every shot involved making up your mind beforehand. Film had some of the physical satisfaction of a sculptor choosing his subject and material and then eliminating all that was superfluous to his or her vision. I liked working with my hands – a trait presumably inherited from my cooper father and every one of his similarly-employed ancestors. I approached every subject through the prism of my own experience and prejudices. The job was to analyse first impressions, pin down the essential, eliminate the superfluous and then gaily use the material to say what you yourself wanted. Objectivity in TV and film is a myth. The same goes for all of our perceptions.

The film editor was crucial. The basic skill he demanded from a director or cameraman was a cutaway to any relevant object in the scene. With this he might execute the desired sleight-of-hand transition from one angle or scene to another. That was until Godard made ‘jump-cuts’ fashionable. Dáibhí Doran always called these little cutaways his ‘bananas’ because of the exotic locations frequented by Fr Joe Dunne. ‘Where’s me bananas?’ was his plaintive cry. From Dáibhí, Merritt Butler, Martin Duffy, Victor Power, Bill Lawlor, Gordon Bric, Manuela Corbari and many other patient people, I learned everything worth knowing about film editing, even how to edit my own work. That came in useful in Connemara when I became the only independent film maker outside Dublin. Now I have the impression that there is a standing army of such foolhardy souls vying for pittances from the Irish Film Board – now titled Fís Éirean, which daringly suggests that the state body might have a vision for Ireland.

Since the microchip has made computers accessible and all the work is now performed on their sophisticated programmes, much of the satisfaction has gone out of the job. I am like a steam train stoker replaced by the diesel engine. The physical approach to the material is obsolete. The director now sits helplessly for hours beside the editor, or is told to come back to-morrow, is sometimes even allowed to voice a suggestion. It is the difference, on the one hand, between the late sculptor James McKenna hacking away for months at wood or stone and, on the other, the subsequent breed of conceptual artists who merely have to state their intentions in order to be taken seriously by art critics.

For a long time I refused to learn the technique of computer editing. Besides, female editors were now in the ascendancy because of their quicker minds and fingers. They also knew that the way to be re-employed was to refrain from telling the director or producer that their material was rubbish. There is no more disillusioned breed than television film editor, male or female. That is part of the reason why the enormous bulk of TV and film today consists of trailer-trash reality directed by schedulers at female consumers. I call it flatpack film and TV. Anybody can assemble it and at the end it resembles product but it falls apart under close examination.

The tail is wagging the dog.

I was lucky. I had so many disparate ideas that I could never hope to express them in formal or traditional artforms. In film I had to filter my ideas through dedicated professional camera, sound and editing people. No matter how chaotic my imperatives might be, those artisans still had to concentrate on their own corner, make sure pictures were appropriate and at least in focus, that the sound was crisp and clear, that the ingredients could be cut together in some coherent way. This was the only process that could have disciplined me and I am indebted to all of those people who kept me up on the tightrope. They are the real artists. We directors are the flippertygibbets and I suppose we have some higher purpose but I no longer can remember what it is.

Alas, in the craven new world of film and TV, the director has slipped down the ratings and now is more like a bus driver, merely keeping tightly to a schedule and subject to ticket inspectors – the bean-counting executive producers. My brilliant director son modestly describes the job as shot harvesting.

The apparatchik reigns, the auteur is dead. So are Kieslowski and Tarkovsky, both at too early an age. My theory is that they died of shock, along with eastern-bloc Socialism which, despite its repression of ordinary citizens, had actually nurtured their genius. The field of art was regarded as a legitimate battlefield between ideologies. Artists were cherished as front-line combatants. When the Iron Curtain vanished so did the concept of film as State-supported art. Those two eminent film makers’ optimistic embrace of Western freedom and democracy exposed them to a harsh market ruled by pragmatism and bean counting. Having survived the heirs of Stalinism they perished under global capitalism.

The irony is that this petty island of Ireland, which always stoutly denounced the evils of socialism and was itself denounced for aesthetic narrow-mindedness, is the only State that now officially and consistently supports the individual artist with an institution called Aosdána. And the politician responsible for realising this vision? The much-derided but far-sighted Charles J. Haughey. He knew that the new economic reality of Globalism would turn us all into homeless beggars or advertising whores.

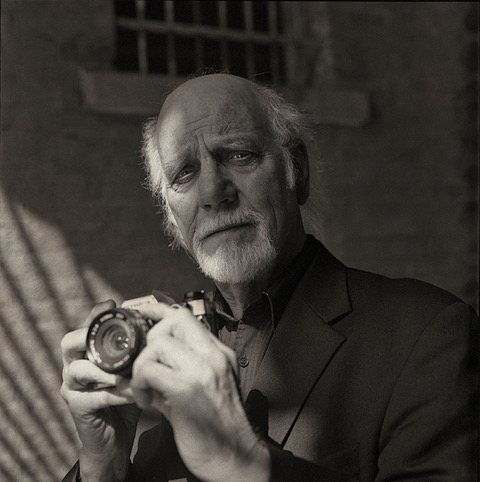

Feature Image: © Hugh O’Conor.

We rely on contributions to keep Cassandra Voices going.