If you follow me baby I’ll turn your money green

I show you more money Rockerfeller ever seen

Furry Lewis, ‘I Will Turn Your Money Green’ (1928)

First of all, it is good to have some of it. Second of all, it is good to have enough of it – which means not too much. I define ‘enough’ as that which allows you to avoid having to have any dealings with bank managers or landlords, or debts or debtors in general.

No one should have to live in constant fear of the spectre of homelessness. No one should have to tie themselves to a twenty-five year mortgage, simply in order to avoid the precarity of the private rental sector (by entering the equal precarity of perhaps not being able to keep up their mortgage repayments to a bank or other lending institution – which are here acting as de facto landlords). No one should have to worry about where their next meal is coming from.

Is an elephant big? Is a mouse small? They are only big or small relative to each other (or to some other object or objects, bigger or smaller than they are). Enough is sufficient. But, given the cost of living where I live (including the cost of somewhere to live where I live, whether renting or buying), ‘enough’ has come to mean ‘a lot’.

Ostensibly, this is a problem of human greed, but its real roots are meretriciousness. Does it really matter whether you live in a multi-bedroom mansion in Killiney or in a two-up, two-down in Stonybatter or Ballybough (from the Gaelic, ‘Poor Town’); in a four-story Georgian house on Fitzwilliam Square or in a two-bedroom apartment anywhere? Is it necessary or desirable to own multiple properties?

The only reason for dwelling in one of the former over one of the latter – outside of having many dependents to shelter, or lots of ‘stuff’ to store – is simple showing off. It is the flaunting of conspicuous wealth and consumption, an ostentatious one-upmanship which betrays an underlying insecurity.

Is it the safety of living in a ‘good neighbourhood’ that you seek, or the status? I suspect that most instances of greed stem from snobbery, which then becomes a vicious circle feedback loop, with snobbery engendering more greed. Which is all the more risible when one considers that most snobbery – social or intellectual – is merely tuppence ha’penny looking down on tuppence.

Image: © Daniele Idini

Hard Working

‘But I have worked hard for it’, say those who have it, sometimes aggressively and other times defensively, and maybe they have. But, under the present dispensation, most people work at something, unless a) they are independently wealthy enough not to have to work, or b) they cannot find or make work. How hard they work is difficult to determine, given the variety of walks of life, and the disparity in their relative financial rewards. Are we talking about physical or mental work? And what about ‘labours of love’?

Many people work less and earn more than others who work more and earn less – mostly because the latter are exploited by the former. Also, implicit in the argument of those who claim to be worthy of their earnings is the idea that they should therefore be allowed to keep most if not all of what they have accumulated to themselves. (One thinks of a former President of the United States boasting that dodging his taxes ‘makes me smart’. It is also worth remembering that we live in a country where Bertie Ahern and Mary Harney think they are deserving of their more than generous state pensions.)

They prize their individual wellbeing, and that of their charges, over the common good, with the masses of ‘other people’ invariably dismissed as too stupid or too lazy to make something of themselves and do well for themselves (and thus, in their terms, they are contributing to society by not taking anything out of it). The premise of ‘When you’re not doing so well, vote for a better life for yourself. If you are doing quite nicely, vote for a better life for others’ would be alien to them, as they believe a better life for others would dimmish a better life for themselves.

So don’t even try quoting the familiar Marxist motto, ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs’ to them, unless you expect short shrift.

But, as David Foster Wallace hypothesised in his last, unfinished novel The Pale King (2011), tax payment and collection is an excellent index of civic virtue. As unlikely hero Mr. DeWitt Glendenning Jr., the Director of the Midwest Regional Examination Center, puts it: ‘If you know the position a person takes on taxes, you can determine [his]whole philosophy. The tax code, once you get to know it, embodies all the essence of [human]life: greed, politics, power, goodness, charity.’

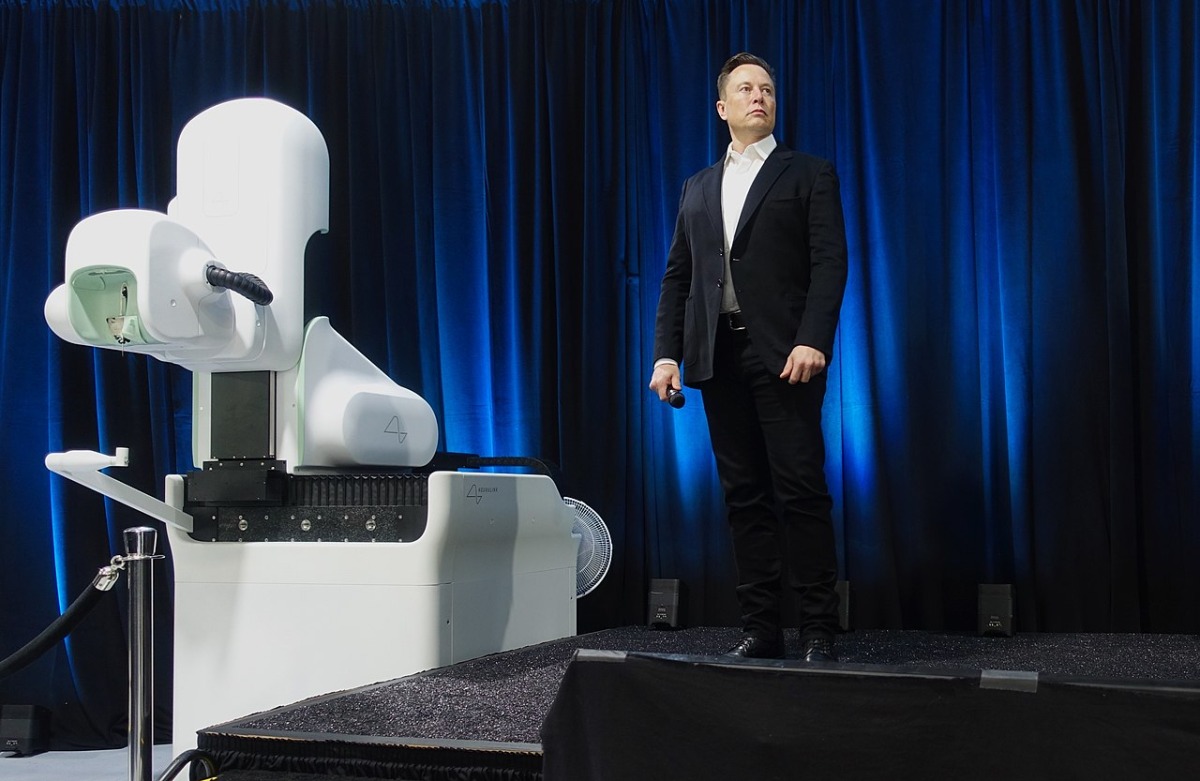

Musk

Juxtapose this attitude with Elon Musk’s warning that President Joe Biden’s proposed ‘billionaire tax’ would eventually increase taxes on everyone else, quoting the hoary monetarist mantra, ‘eventually they run out of other people’s money and come for you.’

FYI, it would take someone on the average industrial wage 800,000 years to earn what Mr. Musk made on a single day in October 2021, a cool $36.2 billion. But, in the eyes of the right, I am ‘just envious’. No, I’m not. Really, I don’t need that much – even if I would quite like to try ‘Life On Mars’ someday – and, given the extent to which our home planet has been run into the ground, may well have to do so. Although, clearly, as a faint-hearted socialist trying to survive in an aggressively late-capitalist world, I would never be able to afford the ticket – not even one-way, let alone return.

Besides which, the glorification of the Protestant work ethic is just a neat trick to get some people to slave their guts out for other people’s profit (cue easy signifiers such as ‘wealth creators’, ‘employment opportunities’, ‘increased productivity’, ‘trickle down’, etc.). Everyone actually, if secretly, knows that – unless you are doing something you like – ‘work’ is vastly overrated.

As Les Murray has it, in his gloss on The Book of Common Prayer, ‘In the midst of life we are in employment.’ Or, as Dennis O’Driscoll recast it, ‘We are wasting our lives, earning a living.’

The whole dream of winning the lottery is that of never having to work for a living again. This is the real meaning of ‘hitting the jackpot’: being able to tell the boss what you think of him or, if you are self-employed, not even having to be your own boss anymore.

As David Graeber contends in his book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (2018), over half of societal work is pointless, and becomes psychologically destructive when paired with a work ethic that associates employment with self-worth. He credits the Puritan-capitalist work ethic for making the labour of capitalism into religious duty: that workers did not reap advances in productivity (or technology) as a reduced workday because, as a societal norm, they have been indoctrinated to believe that work determines their self-worth, even as they find that work pointless.

Graeber describes this cycle as ‘profound psychological violence’ and ‘a scar across our collective soul.’ Yet, as he notes, people are not inherently lazy: we work not just to pay the bills, but because we want to contribute something meaningful to society. The psychological effect of spending our days on tasks we secretly know do not need to be performed, or could be performed by anyone, or by a machine, is deeply damaging.

Frank Armstrong explores the historical origins of capitalism, as the steady financialisation of property threatens the good life we have a right to expect.https://t.co/Lq7z4PeWCP@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @liamherrick @williamhboney1 @KevinHIpoet1967 @VillageMagIRE @RoryHearne

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) September 15, 2021

This abuse is internalised at the level of language itself. Have you ever read people’s job descriptions of their own career summaries on LinkedIN? An example, taken at random:

– – is the M.D. of the European branch of the Australian boutique consultancy – -, where she leads the delivery of impactful and sustainable organisational diversity models, promoting inclusive leadership, collective intelligence, and creative innovation. – – has over 15 years of programme delivery experience and success in the development of cross-sectoral, scaled innovations for learning, informed by evidence-based research. She has a keen interest in interdisciplinary team approaches that promote diversity and inclusion, creative problem solving, leadership development, and change expertise. A former Research Fellow at Trinity College Dublin, – – is an expert on social impact and has a proven track record in the strategic development of pioneering creative innovation models and has presented her research internationally, including at the European Parliament. She is part of Trinity College Dublin’s Women Who Wow mentorship scheme which promotes an ideal collaborative environment to launch new start-up ventures.

What does any of this mean? Lest you conclude that this type of balderdash is the product of Civil or Public Service speak, be assured that it more than extends to the Private Sector too:

I am a Dublin-based Customer Success Manager, with experience across Mid-Market, Enterprise and Global accounts in both Corporate and Search & Staffing industries. I am a trusted partner to my clients and cross-functional internal stakeholders. I use data and insights to mitigate churn, demonstrate ROI and encourage utilisation of the product suite in which they have invested. I am proactive, customer-centric and thrive in fast-paced environments.

This is the worst kind of gobbledegook going. Naturally, it is de rigueur to be ‘passionate about the industry’, rather than stating you have a major concern about putting food on the table and keeping a roof over your head. If you are not a grafter you are surely a grifter.

"The Irish state has been reduced to the role of croupier at a casino table where the super-rich trouser their winnings without being required to even tip the attendants."@frankarmstrong2 argues that human flourishing should be the objective of politics.https://t.co/BVjveb741S

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 14, 2020

Time Millionaires

Add to Graeber’s analysis the concept of ‘time millionaires’. First named by Nilanjana Roy in a 2016 column in the Financial Times, time millionaires measure their worth not in terms of financial capital but according to the seconds, minutes and hours they claw back from employment for leisure and recreation. ‘Wealth can bring comfort and security in its wake,’ writes Roy, ‘but I wish we were taught to place as high a value on our time as we do on our bank accounts – because how you spend your hours and your days is how you spend your life.’ Here she is near-plagiarising Annie Dillard’s brilliant aperçu from The Writing Life (1989), but this idea has a long and noble historical tradition.

In ‘Of Idleness’ (1574), Michel de Montaigne cautions against the dangers of idleness, yet his essays are the product of someone who retired to his country estate at the age of thirty-eight, ‘to spend in privacy and repose the little remainder of time I have to live’ in order to meditate and write, yet it is the ‘thousand extravagances, eternally roving here and there in the vague expanse of the imagination’, of which he is so fearful, which are the fuel for the depth and variety of the essays he wrote.

Samuel Johnson founded a magazine called The Idler (1758-60) and told his readers: ‘Every man is, or hopes to be, an Idler.’

Kierkegaard, in Either/Or (1843), wrote:

Idleness as such is by no means a root of evil; on the contrary, it is a truly divine life, if one is not bored… Idleness, then, is so far from being the root of evil that it is rather the true good. Boredom is the root of evil; it is that which must be held off. Idleness is not the evil; indeed, it may be said that everyone who lacks a sense for it thereby shows that he has not raised himself to the human level.

Learning how to use one’s free time well is the problem, not the leisure itself.

Perhaps the most famous refusenik of them all is the central character in Herman Melville’s short story, ‘Bartleby the Scrivener’ (1853). Bartleby is hired as a copyist, and initially is diligent and hard-working, doing all that is asked of him. Then, shortly afterwards, he presents the narrator, his new boss, with what is to become his catchphrase: ‘I would prefer not to’.

There are several takeaways from this wonderful piece of fiction, but for my purposes let’s emphasise its focus on the dehumanisation of the copyist, the nineteenth-century equivalent of a photocopying machine.

In classic Marxist terms, the story is an exposition of the working man’s existence: oppression under the system of capitalism, in which he is alienated from his labour, offered only subsistence level wages, and is ultimately destroyed by that system if he cannot either conform to it, or change it.

Wilde reclining with Poems, by Napoleon Sarony in New York in 1882.

The Soul of Man Under Socialism

In his great essay ‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism’ (1891), incidentally a pre-twentieth century masterpiece in its reconciliation of aesthetics and politics, dandyism and left-wing thinking, Oscar Wilde argues that:

And as I have mentioned the word labour, I cannot help saying that a great deal of nonsense is being written and talked nowadays about the dignity of manual labour. There is nothing necessarily dignified about manual labour at all, and most of it is absolutely degrading. It is mentally and morally injurious to man to do anything in which he does not find pleasure, and many forms of labour are quite pleasureless activities, and should be regarded as such. To sweep a slushy crossing for eight hours, on a day when the east wind is blowing is a disgusting occupation.

To sweep it with mental, moral, or physical dignity seems to me to be impossible. To sweep it with joy would be appalling. Man is made for something better than disturbing dirt. All work of that kind should be done by a machine.

Walter Benjamin’s vast, and sadly unfinished, Arcades Project (1939) is predicated on his wanderings of Parisian streets, and according to him, ‘Basic to flânerie, among other things, is the idea that the fruits of idleness are more precious than the fruits of labour.’ He also notes, ‘Idleness has in view an unlimited duration, which fundamentally distinguishes it from simple sensuous pleasure of whatever variety.’

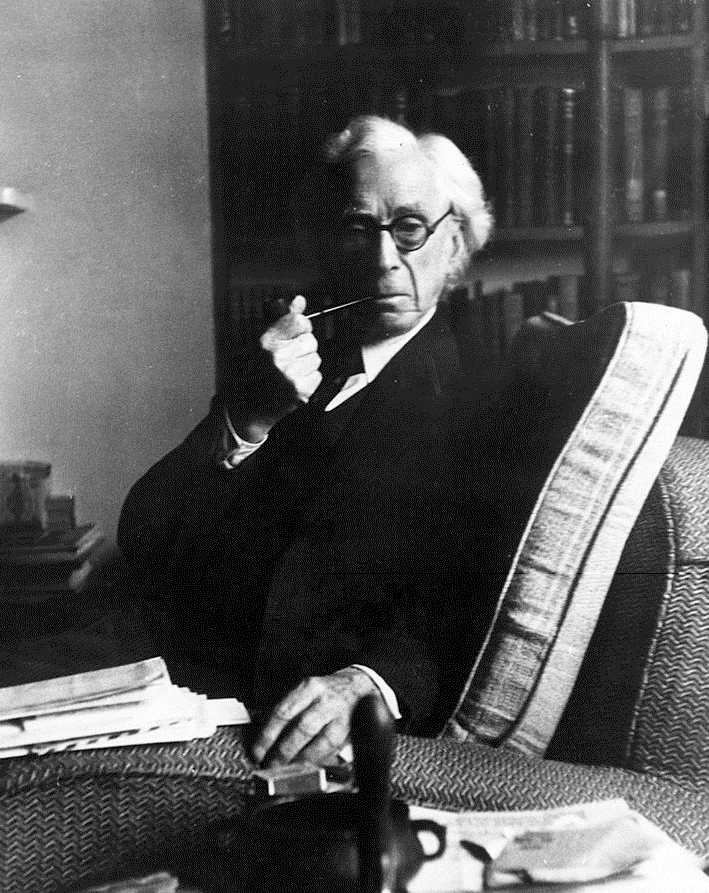

Bertrand Russell in 1954

In Praise of Idleness

Meanwhile, unsurprisingly, in his extended consideration ‘In Praise of Idleness’ (1932), Bertrand Russell has much to offer on the topic:

Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relatively to other such matter; second, telling other people to do so. The first kind is unpleasant and ill paid; the second is pleasant and highly paid. The second kind is capable of indefinite extension: there are not only those who give orders, but those who give advice as to what orders should be given. Usually two opposite kinds of advice are given simultaneously by two organised bodies of men; this is called politics. The skill required for this kind of work is not knowledge of the subjects as to which advice is given, but knowledge of the art of persuasive speaking and writing, i.e., of advertising.

Russell’s most compelling point is the most counterintuitive – the idea that reclaiming leisure is not a reinforcement of elitism but the antidote to elitism itself and a form of resistance to oppression, for it would require dismantling the power structures of modern society and undoing the spell they have cast on us to keep the poor, poor and the rich, rich.

To correctly calibrate modern life around a sense of enough – that is, around meeting the need for comfort rather than satisfying the endless want for consumerist acquisitiveness – would be to lay the groundwork for social justice.

Derek Mahon echoes this theory in his essay ‘Montaigne Redivivus’, from Red Sails (2014), a eulogy to the kindred spirit he finds in his predecessor Cyril Connolly, whom he is anxious to rescue from undeserved obscurity. Mahon fulminates against ‘dumbing down’ (‘done to protect the market economy from criticism and to sell more junk’) and, if leisure is still regarded as a luxury, proposes in place of the lowest common denominator, a concept he calls ‘élitism for all’.

Jenni Odell has expressed similar ideas in her anti-productivity tract How to Do Nothing (2019): ‘In a situation where every waking moment has become the time in which we make our living,’ she writes, ‘and when we submit even our leisure for numerical evaluation via likes on Facebook . . . time becomes an economic resource that we can no longer justify spending on ‘nothing’. It provides no return on investment; it is simply too expensive.’ Odell exhorts readers to recognise that ‘the present time and place, and the people who are here with us, are . . . enough.’

Related themes have been explored, and comparable conclusions reached, in contemporary essays and creative non-fictions such as A Field Guide to Getting Lost (2005) by Rebecca Solnit, and Flâneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London (2016) by Lauren Elkin; and in fictions like Pond (2015) by Claire-Louise Bennett and My Year of Rest and Relaxation (2018) by Ottessa Moshfegh. But the most pleasing up-to-date reiteration of this viewpoint comes in Ms. Bennett’s Checkout 19 (2021):

There’s a fine art to being idle in fact. That’s right, there is an art to it, and very few people are naturally in possession of the gumption and fortitude necessary to pull it off.

Russell accounts for the difference between boredom and idleness in leisure by acknowledging:

The wise use of leisure, it must be conceded, is a product of civilisation and education. A man who has worked long hours all his life will be bored if he becomes suddenly idle. But without a considerable amount of leisure a man is cut off from many of the best things. There is no longer any reason why the bulk of the population should suffer this deprivation; only a foolish asceticism, usually vicarious, makes us continue to insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no long exists.

However, it is regrettable that both Wilde and Russell were unfortunately overoptimistic in their belief that mechanisation would free us all to lead more fulfilling lives. Wilde elaborates his vision of a technological utopia:

All unintellectual labour, all monotonous, dull labour, all labour that deals with dreadful things, and involves unpleasant conditions, must be done by machinery. Machinery must work for us in coal mines, and do all sanitary services, and be the stoker of steamers, and clean the streets, and run messages on wet days, and do anything that is tedious or distressing. At present machinery competes against man. Under proper conditions machinery will serve man. There is no doubt at all that this is the future of machinery, and just as trees grow while the country gentleman is asleep, so while Humanity will be amusing itself, or enjoying cultivated leisure – which, and not labour, is the aim of man – or making beautiful things, or reading beautiful things, or simply contemplating the world with admiration and delight, machinery will be doing all the necessary and unpleasant work. The fact is, that civilisation requires slaves. The Greeks were quite right there. Unless there are slaves to do the ugly, horrible, uninteresting work, culture and contemplation become almost impossible. Human slavery is wrong, insecure, and demoralising. On mechanical slavery, on the slavery of the machine, the future of the world depends.

Russell simply states: ‘Modern methods of production have given us the possibility of ease and security for all (but) we have continued to be as energetic as we were before there were machines. In this we have been foolish, but there is no reason to go on being foolish for ever.’

A reminder of @think_or_swim article from 2020 marking #EarthDay that includes spectacular photography from @danieleidiniph1 https://t.co/m8pTwtfVPT

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) April 12, 2022

Hi-tech Nightmare

Such late 19th century/early 20th century sanguine sunniness now seems woefully wide of the mark, from the standpoint of our early 21st century hi-tech nightmare. Computers were supposed to make all our lives easier. Instead, because of the co-option of these means of production by the forces of Capitalism, they have made our lives immeasurably harder, or at a minimum our working lives – which now don’t stop when we knock off, but continue 24/7. If computers save us time at work, we must do some other work during that time saved. Otherwise, we are shirking.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that entrepreneurship is a specific talent, and those who choose to spend their time engaged in it should be rewarded appropriately. But some people have this gift, and some people don’t, just as artistic or scientific inclination and aptitude is not equally distributed to everyone – even if, arguably, a certain level of functionality can be acquired.

So why should entrepreneurship as a calling be recompensed more generously than others? Why, for that matter, should tech workers earn colossal salaries, while writers, artists and musicians are driven out of the cities they grew up in, because they can’t afford the rent? For the businessperson, Time is Money; for the artist, Money is Time.

But there are more business people exploiting artists than there are artists exploiting business people. As William Burroughs has it in The Job (1969): ‘And what does the money machine eat to shit it out? It eats youth, spontaneity, life, beauty, and above all it eats creativity.’ Incidentally, upon graduating from Harvard in 1936, the privileged Mr. Burroughs was in receipt of a monthly parental allowance of $200 – a considerable sum in those days – which he used to underwrite his corporeal and psychic travels. Arriving with welcome regularity, it guaranteed his survival for the next twenty-five years, and was a ticket to freedom which allowed him to live where he wanted to and to forego employment, and to pursue his psychotropic investigations and reports. As J. G. Ballard has commented, ‘Never has a research grant been put to better use.’

Of course, art – especially of the less commercial variety – has always depended on patronage, whether private or public. No Medici or Borgia families, including the Popes they produced = no Italian Renaissance.

Harriet Shaw Weaver funded James Joyce to the extent of over €1 million in today’s money. Samuel Johnson’s ‘Letter To Lord Chesterfield’ (1755) signalled a shift in relations between artists and private patronage, with Johnson chaffing against what he considered ill-treatment by someone who claimed to be his patron, but did nothing to help him during the years spent working on his Dictionary, but instead tried to steal the glory when it was published. These days, we may thank the Gods for state-sponsored Arts Councils, and place our trust in their judgements.

So, where is all this free money, to finance all the pleasure of all this (un)productive leisure, going to come from, I hear you ask? In my book, Universal Basic Income is a great idea. Food and shelter are basic humanitarian and constitutional rights. In proclaiming ‘By the sweat of your brow you will eat your food’, the Old Testament was wrong, as it was wrong about so many things. To have to work for most of your life, simply in order to keep food in your belly and a roof over your head, will in two hundred years’ time be regarded as a mode of social organisation as ludicrous as the divine right of kings, sponsoring a feudal system. As Ursula Le Guin has written:

Books aren’t just commodities; the profit motive is often in conflict with the aims of art. We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.

Indeed, what is most depressing about the plight of the current under-30s (or is it under-40s?) generation (or ‘millennials’, as they are (un)affectionately known), is their hopelessness in the face of the impossibility of home ownership and an independent adult life, as though they have internalised and are thoroughly resigned to what the late Mark Fisher termed ‘Capitalist Realism’, and have no sense of any possible alternative.

After all, they could rebel, stage a revolution – or even just vote, for all the good it will do, if only just to register a protest – instead of stagnating in frustration and self-pity. In any case, people should be free to do nothing if they wish to, and still have at least a minimum level of security as regards the animal needs for food and shelter. If we can arrange things thus during a pandemic, why can’t we do it all the time? Because it is not sustainable in the long term? I beg to differ. Going to university is essentially doing nothing for three or four or five or six or seven years – except read books – and getting a piece of paper or two or three at the end of it, for your trouble.

David Langwallner argues that we need a Renewed Deal, inspired by FDR's example in 1930s America that will bring Keynesian stabilisation measures.https://t.co/AJbSUjYWfZ@broadsheet_ie @itsmybike @PaulGilgunn @KevinHIpoet1967 @pyjamas_black @mrkocnnll @LumberBob @saoirse_mchugh

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) March 27, 2020

Universal Basic Income

But what would happen if everyone relied on this Universal Basic Income? Well, they won’t. ‘Communism doesn’t work because people like owning stuff’ Frank Zappa told us. I don’t know about ‘owning’ stuff, but I like having stuff, or rather, having access to stuff. But there are many avenues of access to stuff.

Mostly, what is in dispute is how long you have to wait your turn. However, if there was enough stuff to go around, waiting would not be an issue, and neither would ‘owning’, per se. Do you have a mortgage on your home? Then you don’t ‘own’ it: a lending institution merely lets you have access to it, until your make your final payment. But if you really must call stuff your own, then work for the money for your consumer durables, and satisfy your commodity fetishism, when you want to, not when you need to; and don’t when you don’t want to, not when you don’t need to.

But even if everybody did rely on such a subsidy (just as many businesspeople and industrialists already do), it would be no bad – or undoable – thing. For if we institute Universal Basic Income as a minimum at one end, surely we should also implement a Universal Maximum Income at the other, thus having reasonable limits at either end of the scale. The excesses of one will pay for the deficiencies of the other. This is only the next logical step in our current conception of the redistribution of wealth through taxation – or, more plainly, how we move money around to help each other.

Who wants to be a billionaire? I really can’t imagine every filthy rich plutocrat in the world suddenly giving up their extravagant earnings and lifestyle, and settling instead for a modest stipend, simply because they are debarred from infinitely growing their millions.

To be fair, after hitting maybe the 1 billion mark, or 10 billion, or whatever astronomical sum you care to nominate, the monied magnate should simply be taken aside and, like a contestant on a game show, given a prize – a big gold cup, say, or a fancy watch – and told, “Congratulations, you’ve just won Capitalism. Now, we hope you enjoy your retirement. You know, spending more time with your family.” Although, given that there will be more than one winner, and so no outright Number One, the competitive streak in such people may go ungratified, and so atrophy into seething frustration. But, we can throw in the necessary course of therapy – or ‘re-education’ – for free too. I can just see the headlines: ‘Billionaires’ Rights Infringed.’; ‘Freedom For Poor Billionaires.’

Furthermore, so much of the defence of, and endorsement of, mega-wealth is predicated on spurious notions of progress, or planning for the future – but isn’t really any kind of growth at all, except for the advancement of various small groups of vested interests, to the detriment or even outright ruination of the majority of people, and the environment.

At the same time, people in receipt of social welfare payments are frequently characterised as stupid or lazy or both, and dubbed the ‘undeserving poor’ – as though there is suddenly a class of ‘deserving poor’ at whom charity should be directed.

As Wilde has it, in the aforementioned landmark essay, ‘As for the virtuous poor, one can pity them, of course, but one cannot possibly admire them. They have made private terms with the enemy, and sold their birthright for very bad pottage.’

The most egregious local example of this kind of poverty porn was RTE Radio 1’s documentary series Queueing for a Living, which ran from 1986 to 1997, and featured presenter Paddy O’Gorman interviewing people in dole queues and outside prisons. (From poverty porn to property porn – and good, old fashioned porn porn – one has almost run the entire gamut of the western mediascape.)

It is rivalled only by the memory of the farcically counterproductive fiasco that was 1986’s Self Aid, both telethon concert and theme song. Meanwhile, as conservative politicians the world over rail against ‘state-sponsored idleness’, landlords produce absolutely nothing for the income they receive. They don’t even have to do very much to provide the temporary and insecure service they render.

My last landlord – when I was having a break from domestic bliss/strife – was one such specimen. When the bathroom sink in the cottage I was renting from him broke, through no fault of my own, he refused to repair it unless I paid for it. I took the case to the Residential Tenancies Board, and it turned out he was not even registered with them. He then had the gall to upbraid me with the taunt, “You cost me my pension”, and promptly issued me with an eviction notice, under the pretence of selling the property. Of course, in public, this fly-by-night presented himself as a socially-concerned community worker. My nomination for the ugliest word in the English language: ‘rent’ – it tears me apart.

Frank Armstrong examines RTE kitsch on Dermot Bannon's Room To Improve, which allows shit to be denied and for everyone to act as though it doesn't exist.https://t.co/mUP5EV70r5@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @BenPantrey @danieleidiniph1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) May 4, 2022

Was Alcohol Involved?

Or consider the presentation of drug and alcohol addiction in the media: it’s all ‘inner city deprivation’, ‘youth unemployment’, ‘gangster drug lords’, etc. (for example, one of the aforementioned Paddy O’Gorman’s most frequent inquiries of his marks was, ‘Was alcohol involved?’), when the majority of the regular cliental for Class A drugs are the white collar professionals who can afford them.

The same wilful blindness applies to the investigation and prosecution of white collar, as opposed to blue collar, crime. The same double-standard runs through the arts and its practitioners: the only difference between the consciousness-altering psychic experimentation and stress relief practiced by William Burroughs, Keith Richards, and other master addicts, and the guys burgling your house for drug money, is relative income – that is, money. Oh, and talent. Or rather, different kinds of talents.

What is perhaps most interesting about money is how people behave around it, and what lengths they will go to in order to get it. ‘Put money in thy purse’ counsels the villainous Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello. What makes banker/industrialist Mr. Bounderby such a bounder in Dickens’ Hard Times? Why is John Self so messed up in Martin Amis’ Money? Attitudes to money and its pursuit are perhaps the greatest litmus test of a character’s propensity to virtue or vice, in life as in literature. It is the chief barometer of the capacity for Evil. Most people are ‘funny about money’, in some way or another. (Where there’s a will, there’s lots of relatives.) ‘Money is the root of all evil’ is a cliché more commonplace than most, but if we return to Samuel Johnson, he fulfils Alexander Pope’s definition of wit as ‘What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d’, in his great poem The Vanity of Human Wishes (1749) – itself an ‘imitation’ of Juvenal’s Satire X – particularly, for our purposes, in the passage on money:

But, scarce observed, the knowing and the bold

Fall in the gen’ral massacre of gold;

Wide-wasting pest! that rages unconfin’d,

And crowds with crimes the records of mankind

For gold his sword the hireling ruffian draws,

For gold the hireling judge distorts the laws;

Wealth heap’d on wealth, nor truth, nor safety buys,

The dangers gather as the treasures rise.

Watch what people do to make a (dis)honest buck. Or what they’ll do in order to avoid, in due course, having to toil to make a buck. Or if they’ll continue wanting to make even more big bucks, by fair means or foul, long after they have more than any one person, or their dependents, could possibly need. In which case, they are most likely much more interested in power than they are in money, money being merely a means to an end. And the wielding of power is just another way of showing off, or protecting what you have.

In the first of a series on his attitude to having children Des Traynor explores his upbringing and argues that being anti-natalist is not to be unnatural.https://t.co/GnTht5jurt@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @corourke91 @danieleidiniph1 @IlsaCarter1 @KevinHIpoet1967 @GarzonVico

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 1, 2021

Of course, I cannot get through an essay (or piece of ‘creative non-fiction’, or whatever term you care to employ for these ramblings and rants) without making it personal, so I will now refer to my own family background. My father had a strong work ethic, and worked hard all his life in the state transport company ‘to support my family’ – even if his earnings were relatively meagre and his eventual non-contributary pension derisorily small.

But, in those days, so did everyone, since as the old Italian adage has it ‘Chi non lavora non mangia’ (Who does not work does not eat.) Nevertheless, watching him retire, when I was nineteen, I couldn’t help but find it both outrageous and disheartening that he had put in a lifetime’s worth of hard slog for such a paltry payoff. He had missed out on a lot of familial activity (including seeing me), due to doing the overtime he thought was necessary to ‘keep the show on the road’.

Again, as Russell has it: ‘The idea that the poor should have leisure has always been shocking to the rich.’ This perception was accompanied by my late mother – having spotted my burgeoning creativity during my adolescence – inculcating in me the notion that, ‘Art is for rich people.’ Of course, she was wrong. But, in another sense, and certainly from her perspective, she was right. Nor would she have been alone in having such an attitude, which was widespread at the time – one thinks of John Lennon’s Aunt Mimi telling him: ‘The guitar’s all right, John, but you’ll never make a living out of it’ – not that she actively hindered his pursuit of his dream of doing so.

After all, artistic production, and its attendant activities and industries – academia, media, publishing, curating etc. – are still predominantly middle-class occupations, filled by middle-class personnel, who become the gatekeepers to acceptance or rejection. Some will raise the cavil that this perception depends on one’s definition of what constitutes middle class and working class, and if one even allows for the reality of the class system at all.

Typically, these people hold that merely by achieving a college education (however easy or difficult that may be, depending on the personal circumstances you hail from), you automatically enter the hallowed mansions of middle-class heaven. But, apart from being a self-fulfilling prophecy, this is simply untrue, because it takes no account of what has happened before college and what will happen afterwards: your social and cultural capital (what networks and contacts your immediate and extended family have and the milieu it inhabits – i.e ‘who Daddy and/or Mommy know’); and certainly not of your economic capital (how rich your parents – if you have them – are).

For who can finance the ubiquitous internships (free labour for successful companies), without independent economic support, usually from family, without incurring huge debt, on top of student debt? At least rock’n’roll used to be egalitarian, and along with football, recognised as a ‘working-class escape’.

Nowadays, you can go to college to learn how to be a rock star, or go through an academy to develop the necessary footballing skills – which makes either endeavour seem rather more anodyne. Everyone may now be entitled to a degree – but only because you can pay through the nose at a private college in the event that you did not achieve the necessary academic requirements for entry to a ‘proper’ university.

Seventy percent of the world’s population may live three pay cheques away from financial disaster – but life is definitely easier when you have a safety net. If worse comes to worst, some people can always ‘move back in with the folks’.

Others have no folks to move back in with – or the prospect or the reality would be just too difficult, for either or both parties. All of the foregoing makes it hugely problematic for people of working class origin to establish themselves in any profession, but it is especially and acutely true for writers, artists and musicians, particularly if they are producing challengingly avant garde work. Racism, sexism and homophobia are all terrible prejudices, but can they exceed the obstacles created by the structural inequality of being working class – the poor, often elided, back-of-the-bus section of intersectionality?

Launching a career in literature was and is a more onerous undertaking for university educated women writers like Jeanette Winterson forty years ago, or Claire-Louise Bennett more recently, in contrast with their middle-class counterparts, because familial understanding and support may be minimal or unforthcoming or non-existent. Then, if you do happen to gain some recognition, you have to deal with the condescension of being made a token example of: if they can do it, anyone can. When I think of the undeveloped or underdeveloped potential of so many exceptional people, juxtaposed against the developed or overdeveloped potential of so many average people, it can fair make my blood boil.

Bye the bye, even further back, during my prepubescent boyhood, my maternal unit also gave me the lowdown on the evils of Russian Communism. Russia was this dreadful place where everyone was forced to believe the same thing and behave in the same way (so unlike Ireland, where we had freedom!), and they didn’t believe in God, and they were just waiting for a chance to invade Ireland, and make the whole world Communist, and they would surely martyr me for trying to defend my Catholic faith and preserve my immortal soul. I can see now that she was just another victim of the paranoid Yankie Cold War propaganda that was rife at that time, since Ireland was a vassal state of the U.S.. Still, it was quite a heavy and fearsome burden to lay on a small, impressionable lad with an active imagination. Thanks Mom.

Read history, any history. It is essentially the repeated story of the stronger exploiting the weaker, so that they can become richer while the others become poorer. You can dress it up with any fine justifying notion you like – crusades against the infidel, the white man’s burden, survival of the fittest, bringing the benefits of ‘progress’ to backward, uncivilised people, protecting ‘the gentle sex’ – but it doesn’t say very much for human nature. In fact, when I consider the outlandishness of the excuses usually trotted out, I prefer those with an eye to the main chance who are honest enough to admit that they are just self-seeking, self-serving, land-grabbing and fucking everyone else over for the money, without bothering to proffer any fancy reasons for their rapacious cruelty. The capitalist is at base a common or garden playground bully; the rest is just PR to cover up the fact.

Yes, Communism doesn’t work, because people like owning stuff. But Capitalism doesn’t work either, because it means too many people cannot own stuff, because other people own lots of stuff, at their expense. Mostly, neither of them work because of human frailty and venality – but Capitalism grants much more free reign for these traits and their spawn – aggression, callousness, selfishness, deviousness – to run rampant. Indeed, it is difficult to imagine that it could function as designed without encouraging them, however covertly. Flaubert, as Julian Barnes tells us in Flaubert’s Parrot (1984):

thought democracy merely a stage in the history of government, and he thought it a typical vanity on our part to assume that it represented the finest, proudest way for men to rule one another. He believed in – or rather, he did not fail to notice – the perpetual evolution of humanity, and therefore the evolution of its social forms: ‘Democracy isn’t mankind’s last word, any more than slavery was, or feudalism was, or monarchy was.’ The best form of government, he maintained, is one that is dying, because this means it’s giving way to something else.

Wilde, again in ‘The Soul of Man Under Socialism’, presciently agrees: ‘High hopes were once formed of democracy; but democracy means simply the bludgeoning of the people by the people for the people. It has been found out.’

But of all the governmental systems humanity has already devised and tried, European-style social democracy would still seem to be the best bet yet. (Ireland, alas, in spite of E.U. membership, remains part of the Anglosphere, having thoroughly embraced the neoliberalism of the U.K. and the U.S..) Not that it couldn’t be improved upon – in ways I am ill-qualified enough to know I should not expostulate on here.

For it is certain that the first economic strategist who comes along will undoubtedly point to the fact that I am suspiciously short on detail in my surely flawed and embarrassingly naïve socio-economic analysis. I freely admit that I am no dismal scientist – in Carlyle’s sense of advocating for slavery, but rather a gay scientist – in Nietzsche’s sense of the art of poetry; or at least or at best, a sceptical artist. In the classical humanist tradition, I am basing my report on my lived experience, and that of those around me.

I have never flown first-class. I have never even purchased a first-class train ticket. I have no idea or experience of what it must be like to live as one of the super-rich, although fictions like the HBO television series Succession, to say nothing of practically every nostalgia-fuelled costume drama that has ever been commissioned, try to give us some inkling. Some people watch to ogle the wealth and lifestyle; I feel dirty after watching all those horrible characters doing terrible things to each other – but I keep coming back for more. To quote from Beckett’s Endgame (1957):

CLOV: What is there to keep me here?

HAMM: The dialogue.

Money Doesn’t Exist…

Ultimately, money doesn’t exist as a tangible entity. It is merely an abstract medium of exchange for goods or services rendered. A €20 note is not worth more than a €10 note, except by mutual agreement between interested parties as to what is written on them signifies.

Similarly, the stock market, and all such investment, is a giant, reciprocally arranged, confidence trick: if everybody buys in, regardless of external influencing factors, then values increase, or at least remain steady; if some people get nervous, and pull out, then others will follow suit, and the whole shooting match comes tumbling down. That’s why we have an incessant cycle of booms and busts – not because there is too much oil or not enough oil, or even because we no longer need or want oil.

The invention of credit (and its consequent debt) is what keeps people in thrall to this system. One thinks of the anecdote about Donald Trump pointing to a homeless man one day when he was $1 billion in debt, and telling daughter Ivanka, ‘See that bum? He has a billion dollars more than me.’ Not that this observation was of much consolation to the tramp – however much it may have been to Trump.

This is what makes the ending of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) so poignant: of all the things we strive for, money seems the least essential. Gatsby, the self-made ‘new man’ millionaire (and how did he make his money? – everyone has some dark, speculative theory about his past), has sacrificed everything for financial success and status, and achieving the American Dream has destroyed him. To put it simplistically, when it comes to his infatuation with Daisy: ‘Can’t Buy Me Love’. ‘And so, we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.’ The vanity of human wishes, indeed.

Like the Philip Larkin of the eponymous poem, I cannot help rueing the extent to which money controls and limits most people’s lives – those who attach much importance to it and strive, successfully or unsuccessfully – after it, as much as those who, through either ineptitude or lack of interest or a surfeit of basic human kindness, do not make a priority of pursuing it and so rarely have enough. And how it also separates us, where we live, and where we live in where we live, and how we live in where we live, while great impersonal institutions hoard, indifferently, merely dispensing charity occasionally, at their whim – after they have taken care of the shareholders. The business of business – in fact the whole money game – is, indeed, ‘intensely sad’.

I listen to money singing. It’s like looking down

From long french windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun. It is intensely sad.

N.B. Desmond Traynor gratefully acknowledges the assistance of funding from the Arts Council of Ireland towards the completion of this and other essays.

Featured Image: © Daniele Idini