And the people came from far,

And they came from near,

To see the troubadours.

From ‘The Troubadours‘ by

Van Morrisson.

I – Lockdown Daze

I was strung out on the bed, for the zillionth time, listening to a Van Morrison record. For a large part of the lockdown Van’s music played over and over. I walked the driveway at Glenstal Abbey in the evenings with my dogs, mostly in dark. And most of the time, I would side with Van: his music luring me into the ‘viaduct of a dream.’

The lockdown isolation was anything but a lightning rod for the imagination; but music was a panacea for the humdrum banality of days lurching into each other. Music satiated my thoughts as I wandered up a driveway originally designed by the Barrington family in the nineteenth century. The same estate was handed over to the Irish state in the 1920s and handed over to the Catholic Church later. It is now Glenstal Abbey, a Benedictine monastery and elite boarding school for boys.

Every day I walked the dogs, one a mature border collie, the other a young puppy of the same breed, to the top of the driveway, I imagined a different century. I would enter the ‘viaduct of a dream’ Van sings about on ‘Astral Weeks’, the song from the album of the same name that has been my guiding light since my teens.

And to further escape the banality of lockdown my mind would conjure up a time when the young mistress of Glenstal, Winnie Barrington, rode her horse along the driveway, her friend following on a bicycle, en route to Newport.

There she would encounter the notorious Black and Tan officer, Ronald Biggs and his entourage. They would drive to their death at Coolboreen in Tipperary – killed in a rebel ambush during the War of Independence. Winnie had worked as a nurse during WWI in London, and her savage death – many believe – sparked the familial retreat.

And as the spirit of Winnie’s seemed, for me, to linger somewhere on the landscape, pushing into my thoughts, Van’s focus on rebirth on the song ‘Astral Weeks’ was like a sumptuous call to the imagination. It triggered my desire to escape the lockdown boredom. I would imagine Winnie, a woman gunned down a century before (May 21st 1921) engulfing the spirit of a puppy called Janey Mac.

Janey Mac.

Janey Mac, a gift from a friend the previous September, was a handful for six months. Border collies are such energetic, intelligent dogs that to raise one is not entirely different to raising a child. A certain level of care and attention is required. They push you to your limits, bite at your ankles at dawn, chew treasured sofas, display an incessant need to engage everything in sight. And then, just as you begin to reach the tether of your wit, along comes a lifelong companion, attentive to every need.

The tarantula becomes a soul mate, as close to you as a family member. The rain kept pouring down as the dogs pulled me along the former Barrington Estate. I imagined the ghost of a woman dead almost a hundred years to the day passing into the soul of a little collie pup. ‘Could you find me,’ Van sang, ‘could you kiss-a my eyes, lay me down, silence easy, to be born again.’ ‘Born again’? As the Indian mystics say.

Winnie Barrington.

The same evening, I was sprawled on my bed, having just finished a short manuscript that gave expression to these ideas in prose. The manuscript weaved the facts of the assassination on Winnie and Biggs a century prior, into a tapestry of the imagination.

Janey would embody the young mistresses’ ghost, and I would bear witness to rebirth: the phrase ‘to be born again’ simmering in my thoughts as I walked the driveway each day. In my mind it was no mere coincidence my daily walk with a puppy in tow was taking place a century after the ambush had led to the young woman’s untimely death: it was an arrow pointed in my direction from the angel of history. I would tell her story in my own way.

I would draw inspiration from music. I lay on the bed googling upcoming Van Morrison concerts, as answers began to trickle in on-screen. For some reason I purchased – tired and wine sodden – and with an electronic swish of the hand, two tickets for a rescheduled festival gig in Derry that coming November. It was still months away. The Delta Wave was consuming the airwaves and the pandemic seemed never-ending. I was nervous. For two years I had been working from home, with intermittent days on site. I was a natural extrovert confined to a small circle of contacts.

Most of my free time at this time – mostly in the early hours of the day – was taken up writing interconnected stories about the border collies in my life. The second, From This World, is a fiction woven from within the ‘viaduct of a dream’ – the imagined life that hovered like a ghost over the surrounding landscape. I would travel back in time, back to an Ireland before independence – when corncrakes sung out in nearly every valley – and when vast swathes of land lay unclaimed by commerce.

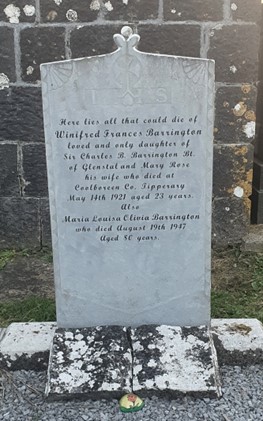

Along the driveway the dial on my phone would always seem to congregate on the name Van Morrison; ‘Crazy Love’, ‘St Dominic’s Preview,’ ‘Sweet Thing’; songs that directed my thought to the story of Winnie like an obsession that would not relent until her death made its way onto the page. I sourced material from journals, sought people from the village from whom the story had been passed as a product of myth as much as truth, visited her grave in the cemetery. I even hovered around the Church of Ireland in Abington thinking of her playing with friends before Sunday service.

Abington’s Church of Ireland church.

In the end, the limitations of the factual confronted me. No matter how much rooting I did, how many articles I read, the same hollowed truth edged out: we must always imagine certain details of the past. In uncovering the myths of the ambush, piecing together reasons for Winnie’s motivation in travelling that day into a text worth reading, I would set upon the same thing set upon plodding through the fields listening to ‘Saint Dominic’s Preview’: imagination. I imagined Van wandering the streets of San Francisco, thinking of home. Suddenly, a sign for a forthcoming mass dedicated to peace in Northern Ireland at the Church of St. Dominic appears.

Entrenched in thought, mystery overcomes him: someone, irrespective of religion, is thinking of his home in a corner of the world. ‘It’s a long way to Belfast city too’ he will later write, San Francisco and Belfast City edging close together in his heart. All around him is a banal conformity, preying on the modern urban city.

Some otherness of spirit has materialised in this unforseen act of care: prayers offered in a distant church for the Troubles in his homeland. Years later, as if these prayers have been answered, a US envoy helps to broker peace in Northern Ireland. And around the same time, I begin to suspect, Van starts to think about the album he will call The Healing Game. The album is a much-heralded return to form for the singer; a compelling vision of healing in its many forms.

I was on a long journey through a catalogue of music while dreaming of a dead woman, letting each of Van’s albums spark new ways to think about landscape. The Waiting Game played a role. Alone in my thoughts one evening the first side played through. The song ‘Waiting Game’ shuffled into the light with its recognizable harmonica. ‘I am the observer who is observing’ ushered forth in those enticingly vague lyrics, giving no indication that the song is anything but a personal lament. Perhaps Van is passaging through middle age, seeking ‘the presence deep within you.’ But it is the same presence he calls ‘higher flame,’ in possible reference to the wait for peace in Northern Ireland. Here’s the thing: it was a spiritual quest I identified with in these songs; a yearning to connect with something beyond the material grist. Is it possible the goal of Van’s search in song is the same thing that I was yearning for?

In the early days of the pandemic, before Winnie’s story gelled in my mind with the music of Van Morrison, I spoke for some amount of time with a priest about the effects of isolation; the wave of destruction he believed would result from delayed grief. We stood outside a church in conversation.

My thoughts began to drift back to a time when I had stood in a funeral parlour, shaking hands with the different people who came to pay their respects. My hands were so badly blistered after. Yet the procession of people, their faces contorted in shock, was a panacea for the grief that would begin to manifest in the months that followed. What might have happened without that show of tradition unique to Ireland and its culture, I thought? A delay of sorts. A drift into unfettered pain: a world without others to soften a fall?

Re-listening to The Waterboy's Fisherman's Blues, Dara Waldon's recalls the West of Ireland he once knew, scattering ashes of memory as far as Ballyconneelly.https://t.co/TNdJTnWlsw@broadsheet_ie @WaldronDara @corourke91 @KevinHIpoet1967 @MickPuck @BowesChay @FutureVisions5

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) December 7, 2021

The faces that evening were pillows laid out in time. When removed a body would fall on a cold floor. These thoughts came to me outside a church while I was talking about death with the priest of a religion I no longer practiced, each of us struggling with the covid restrictions in our own interminable way. Our two-bit conversation brought some relief from the sudden descent into a half-life of zoom classes and waited upon DHL deliveries. At that time my social life consisted of one weekly outing: a trip to a supermarket to see those waiting in line.

Then something strange happened during the lockdown. I was listening to Van Morrison records when Van began speaking out about lockdowns and restrictions on musicians. Rolling Stone ran a story about Van as anti-lockdown.

Then Van took to YouTube in defense of his views. The comments below his video post unfolded in a spew of hate. He was selfish, inconsiderate in wanting to play live music. He was working on Latest Record Project, a record with a considerable number of protest songs rallying against the state’s incursions into his life.

For Van, the lockdown policy was a gross overreach, an intervention he felt lacked scientific proof. Fair enough, I thought at the time. Our world is made of different points of view. But then I began to think about these statements in relation to my own frustrations. Was it really that strange that a seventy-five-year-old old man wanted – in whatever way possible – to play live during a pandemic?

‘Stay home, stay safe’ was the public health moto of the time but it was far too obtuse in the way it equated isolation with being safe, particularly at a time when the WHO called isolation a major killer. So much public health policy in the period leading up to that time had focused on ageism: attempts to determine a person’s value based on age alone. Van was ageing. He wanted to play the music that defined his profession. Like me, he found it frustrating to stay away from others. Beyond everything, I admired his honesty in speaking.

But suddenly Van’s name brought the baggage of Covid 19 politics to bear on pop music. Lifelong fans dumped his catalogue in a show of partisanship. Van called out Northern Ireland health minster Robin Swann for intervening in his life. He did not help himself when a video began to circulate of him cavorting with Ian Paisely jnr. in a Belfast hotel. Undoubtedly irked by the ban on music events in Northern Ireland, maybe at his age, I thought, time was slipping away.

Each minute away from the stage was an incursion into a life of music. Was this selfishness? Was it a lack of concern for those who believed we could defy the virus? Or was his decision to risk his health to perform music for others something eminently admirable in him? I lay on the bed thinking about this, as the needle dropped on a cover of Van’s ‘Sweet Thing’ by The Waterboys from the album Fisherman’s Blues. Then, all at once, the next song played. ‘Strange Boat’ seemed to reach from the past into the present:

We’re living in a strange time

Working for a strange goal

We’re living in a strange time

Working for a strange goal

And then – of course – the conclusion:

We’re turning flesh and body into soul

Things then began to click. At Abington cemetery the epitaph ‘here lies all that could die of Winifred Frances Barrington’ appeared on a newly renovated gravestone. Flesh and bone withered away, leaving something of a ‘soul’? It was an ephemeral quality that had lost currency in our time. And just as The Waterboys turned their strange times into a spiritual quest, it felt I was searching – not even consciously so – for something eternal in a world defined by fear. It was fear directed at a future point; a time that might never even materialise as real. Every evening I walked into the blanket darkness of the pandemic night, the ghost of a dead woman breathed down upon me. I moved into the ‘viaduct of a dream.’ It began to dawn on me I was searching for something that had yet to die, something known in the vernacular as soul. ‘Chambois, cleaning all the windows’, I heard Van sing on ‘Saint Dominic’s Preview’ – a metaphor he returns to on mid-career masterpiece ‘Cleaning Windows’ — before stressing, ‘singin’ songs about Edith Piaf’s soul.’ Maybe Van’s window cleaner is a soul seeker, I thought, cleaning away the grime that prevents us from seeing clearly?

In my imagination Van was standing on a Derry stage singing ‘Cleaning Windows’, the lights shining down. Love, labour, the transcendence sought after in the blues dwindled into rock n roll bliss. Is there a beter celebration of pop as a panacea for the ills of working-class life, I imagined, than a song about a window cleaner who dreams of Jimmy Rodgers? Perhaps not?

The song, beyond all of Van’s songs, concerns perseverance in the mundane: physical labour typical of urban life. As I started to dream of a journey North, passing from County Limerick to County Derry, passing along the stonewalls of Galway and Mayo, against the looming shadow of Ben Bulben, a crystalline image of a window cleaner formed in my mind. The image ushered me back to a summer spent packing tiles in a Bavarian factory. Loneliness and boredom marked each passing day. What did I dream of then? Was it music? Love? Was it the desire to turn flesh and body into soul?

All the time away from family and friends during the never-ending pandemic impacted upon on me to such a degree I yearned for some kind of mystical experience: a kind of commune. On ‘Deadbeat Saturday Night’ Van gives voice to a similar craving, a yearning to escape the daily grist and to finally to sing for others. ‘I’m alone, telephone, virtual reality,’ he bristles angrily, ‘it’s no life, no gigs, no choice, no voice.’

Latest Record Project is made up of protest songs slammed by critics. More online criticism surfaced on its release. Van was called an anti-vaxxer, conspiracy theorist etc. There was even talk of burning his records. It was difficult to express a judgment of Latest Record Project without succumbing to the politics of the pandemic: the pro or anti binary regarding lockdown.

Rarely had the politics of popular music been so intensely focused on a singular point of view in my lifetime. One evening during the lockdown – long before I began contemplating journeying North – I looked for inspiration in old live albums, turning eventually to Nirvana’s Unplugged.

As the album played out, all knowledge of the junkie Kurt Cobain became in later life, prisoner of his body, seemed to dissipate in a moment of soul. Beyond the opprobrium of fame and celebrity, beyond the cravings of a drugged body, was a sense of peace. ‘I formulate infinity,’ Kurt sings on the band’s sumptuous cover of The Meat Muppet’s ‘Oh, Me’ cushioning the lines by saying ‘and store it deep inside me.’ Years after death something like a soul still resided as the aura of the physical record: the infinite.

II – Northbound

You were only waiting for this moment to be free..

‘Blackbird’

The Beatles.

The night before the journey North I had two dreams. Both would resurface in my consciousness when driving the next day. In the first dream I was walking in a forest. A metal object in the shape of a breast stared up at me. I turned to look around, peering through the gap in the trees, as the sun made its way in through the branches. A bird swooped down upon me, its lifeforce fading in my presence.

I picked up the body to see if it was dead, before attempting to replace its breast with the metal object that had been left on the ground. But I was unable to make the object work. Instead, I ran home in tears.

In the second of the dreams, I was lying on a steel bed in a room that formed part of an office in a university accommodation. Several staff members were welcoming me onto a campus in a country that seemed to be somewhere in Eastern Europe. I mentioned that the lodgings were perfect for my stay and that I planned to stretch my legs. The others got up to leave the room, smiling at me, saying goodbye in a broken English. No sooner had they gone than a sudden urge of excitement – one that travel brings – overcame me. I got up from the bed, grabbed my jacket, and checked around for my keys. I tentatively opened the door to discover the apartment was on ground level, situated at the center of an old Roman university. The door opened to a sea of students moving at pace. They were all bunched together into groups, in deep conversation.

There was something unusual about the second dream: none of the students wore face coverings. There were just faces, of which no two are the same. It was a thought that heralded my waking up: no two are the same. Life had returned to normal. The lockdown was over. I was on route to Derry, thinking of where to stay in Sligo and of what to do while in Donegal.

Once I got to Ballyboffey a friend would drive us to Derry. Everything was planned to get to the gig on time but the dreams, so incredibly different in tone, troubled me. I mulled over their content pushing into a turbulent sky. The dying blackbird had brought such sadness I immediately fled the forest of my dream.

In contrast, the second dream brought some elation. All the months of isolation, unable to identify the faces of people I met in shops, relented into antithetical bliss. Were the dreams an oracle of the future? A wish? And if so, was the blackbird shorn of its essence? Why did faces bring such elation? What did it mean? The time I had spent thinking through the two contrasting dream sequences passed quickly when driving. Then it appeared on the landscape like it always does: a signal of majesty in the land.

Image (c) Daniele Idini.

Ben Bulben towers over the county of Sligo like a beached whale. It interrupts all movements of the gaze. We stand aghast in its shadow. Once it appears the mystery of the landscape also makes itself known.

As you follow the sign for Bundoran, when bypassing Sligo, Ben Bulben meets your every gaze. I had planned to walk at Mullaghmore, before pulling into a B&B for the night. But no sooner had I arrived at the car park and stepped out of the car to begin walking, then along came a torrential downpour.

Image (c) Fellipe Lopes

It was near impossible to appreciate the views. An elderly woman, decked out in the gear needed to survive the weather, saluted at me while walking with her dog. ‘Not a bad day for a walk’ she said smiling. But I was soaked to the bones, and my jacket was still battling hard to resist the rain. I saluted back at the lady before closing the car door and taking a deep breath. I was glad to escape the weather. Twenty minutes later I drove through a village that, because of the rain, was difficult to make out by name: not knowing whether I had ventured into the North (as Donegal is known in the vernacular). Usually, it is clear: hillside sheep signal an untrammeled beauty in your midst.

It was at that point a small B&B sheltering a little shebeen-like pub appeared on my eye line. Both establishments seemed like variations on traditional cottage style, devoid of the thatch roof typical of pre-nineteenth century builds (signifiers of an older time persisting in the present).

I rang the B&B bell a few times before a hunched over woman suddenly appeared inside the door. Her mask concealed a smile, her soft Northern brogue welcoming in tone. A room on the ground floor was available for a night, she said, and a Chinese takeaway would open in the village at seven.

The pub didn’t do food since reopening, apart from toasted sandwiches, and there was no restaurant in the vicinity. If it was cooked food I was after – I think she meant a gastropub – I would have to drive to Donegal town. Whatever the name of the village – and I didn’t want to know given the point of the journey was to cultivate uncertainty – drinks followed by a takeaway seemed more than an ideal proposition.

I had a shower in the room, changed clothes and did a little jig to celebrate the unknown breaking through the habitual. The jig was designed to augur in the wrenching back of a spontaneity from the clutches of the Covid pandemic. I was at the pub in minutes, ready to forget the rain.

It took me some time to locate the cert adopted for pubs and restaurants by the Irish government, before I stumbled in the door. Since the restrictions were introduced, I had hardly ventured near a pub, feeling a certain unease with everything: the virus and the regulations.

Maybe it was a distrust of authority, a yearning for the old ways. But once I had opened the door, expecting to see one or two people, the artificial light was blinding, like it was battling the darkening of winter. A young man – with a moustache and a Kangal hat turned the wrong way around – appeared on my right behind the bar. A sprightly young woman was stood beside him. The bar was full of drinkers in breach of the protocols. My instinct was to turn away, but the occasion lured me in. It was a ‘life before’ that called to me.

On the bar counter baskets of sandwiches were sitting beside baskets of cooked food. It seemed like I had interrupted a party. There were people standing at tables, sandwich and sausages baskets untouched, yet no television or music was on that would distract from conversation.

The lights were blinding bright. I crept to the bar, trying to blend in as best I could. Faces turned in my direction: I was taken aback by the groups of people together. It was like stepping back in time. And then the occasion made itself known. I had arrived at some kind of Irish wake. A blown-up photograph of a man’s face was placed at the cabinet bar.

It was the familiar that me pushed me in the door. I would come to learn of the man in the photograph’s fate when ordering my first drink, once it had seemed ok to intrude. The people at the bar welcomed me in without any fuss. Although difficult to understand the brogue, to adjust to the old way of life – a culture temporarily replaced with the public health protocols of the Covid pandemic – that had vanished to such a degree in the years that had passed since the pandemic began, I settled in at the bar. It was just folk waking the dead in the only way they knew. Soon I was helping them on their way.

Public houses, bars subject to much criticism during the years of the pandemic, saw purpose return as a place of communion. We come to drink and remember. We come to raise a glass to the eternal: the soul that lives on after death. A local GAA man, wearing a green and yellow Donegal scarf, returned from the toilet to take his seat beside me. He spoke about a ‘wild sadness’ that had befallen the village.

But, in truth, it was not all sadness. It was a scene I understood: a ritual of sorts. To raise a glass is to say – in the gesture of a tradition – ‘we miss you.’ You, the other person, one of a community transcending the ‘I.’ The time that I spent in the pub was a sort of unexpected gestural confirmation of what the journey North was meant to affect. All the isolation of the previous months gave way to something immeasurable. I stayed to hear about the man in the photograph; to hear he left the pub in good spirits; waving goodbye to his friends in good health. He was known all around for his wit, the numerous pranks he liked to pull on friends.

The man’s face stayed with me as an image waiting in the rain beside the local Chinese takeaway in a village that name of which I cannot recall. As I write now, I wonder did the village exist? Did the pub exist? Or had a dream taken the place of reality?

Two friends had passed away during the pandemic. When news broke, I walked country roads trying to repress a desire to jump in the car and drive; to pay respects in whatever capacity possible. On one occasion, my group of friends took to a Zoom meeting as a virtual substitute for the pub experience. We wanted to raise a glass to a friend, celebrate his life. But the screen meant to connect people seemed to contradict the message it was meant to impart.

Cut off from the other, material bodies were mere images, dependent on the vagaries of a Machine. At any point the connection could break, the face of another no longer visible. Presence is shadowed by an imminent threat of absence: a void that can swallow up the connection at any given time.

I returned to the B&B with a fried rice in one hand and my phone in the other. In the distance Ben Bulben bore down like a God of the mountains. There was such a mystique to its presence: a gateway into the sublime landscape of the Northwest. When driving the same landscape the next day, bypassing Donegal town in the process, I took the decision to stop at Murvagh Beach. I wanted to gaze across the terrain – so impressive in reach – at the cliffs of Slieve League.

In more accessible counties, the cliffs would attract huge numbers. The morning was taken up in conversation with the proprietor of the B&B, a retired lady in her late 60s, over cups of tea. She said the cliffs viewed from Murvagh are the biggest in Europe.

A few hours later I was waiting in my friend’s car outside Jackson’s Hotel in Balyboffey for him to return. A river bridge was at my rear, like a postcard. Its autumnal colour seemed designed for the gaze. Tommy would drive that evening, once we had eaten. The last stage of the journey North would see us lost in conversation. Time would pass unnoticed. Darkness soon began to cover the night as our car moved from country roads into Derry’s urban décor, a contrast to the distant bogside. We passed by the new developments along the river, before a P sign stood out for a carpark Tommy said was in walking distance of the Theatre. Once we had parked and arrived at the Theater, the concert goers were waiting outside, ready to enter.

The venue was practically full when Van and his band arrived on stage. Van was a diminutive figure who had lost a significant amount of weight. He was an elderly man with renewed purpose. From our balcony seats we could gaze at the band from ahigh. Wearing black sunglasses and a trilby hat, Van had the aura of a singer finally given back a stage; happy to know he could do his job again.

For the duration of the show, he just leapt from song to song, never speaking directly to the audience. He began the gig by playing songs from his most recent album, all – to some degree – commentaries on the stay-at-home orders he was so critical of. But he then went on to play a load of songs from his back catalogue that drew me in so many different directions. ‘Sometimes We Cry’ was a cue for joy, Van moving between numerous instruments during the song, his saxophone like a magical wand.

Awe of a sort arrived with ‘Baby, Please Don’t Go,’ drifting into a rendition of Muddy Waters’ ‘Got My Mojo Working,’ signaling that we were witness to a great blues musician and testament to a lasting tradition. It was also testament to the power of live music, a feeling the performance of ‘Cleaning Window’ confirmed. I had played the song repeatedly throughout Covid, trying to harness the pleasure of labour and music in our youth. But it soon began to dawn on me, however, as I gazed upon an elderly man singing ‘what’s my life?’ that Van was asking his audience an important question. Is to sing for people – nothing more – a source of our being?

It was the affecting moment the journey North was intended for: the words ‘no 36’ sang in a soothing Belfast twang. Van has a singular (as an artist) ability to alter intonation to maximize lyrical affect. The way he sings ‘No. 36’ in a Northern accent is one example. But there are many. ‘Angelou’ builds by way of difference and repetition, ‘in the month of May, in the city of Paris’ repeated with intonation amplified each time.

The music, all the while, builds in tempo. Van left that evening after two hours performing on stage, departing the scene with an affirming rendition of a song that personifies the above-mentioned lyrical affect: ‘Gloria.’ Once he had left the stage the band members went solo for a few minutes. The crowd then began to clap and sing along with the remaining musicians, shouting ‘G-l-o-r-i-a’ in something of a fervour. I looked around, thinking, for no reason, of Winnie, of Janey, of lockdowns and isolation. Then a strange sensation came over me: a grandiose feeling of hope.

In 1978, ten years after the release of Astral Weeks legendary music critic Lester Bangs wrote,

My social contacts had dwindled to almost none; the presence of other people made me nervous and paranoid. I spent endless days and nights sunk in an armchair in my bedroom, reading magazines, watching TV, listening to records, staring into space. I had no idea how to improve the situation and probably wouldn’t have done anything about it if I had.

Lester’s reflections chimed with my own experiences during the stay-at-home policies of the pandemic. The famous critic found in Astral Weeks something of a spiritual retreat: an album that helped release him from paranoia’s clutches. Lester’s was a dilapidating malaise, a condition pushing body and soul into competing realms.

Astral Weeks was a Godsend. The album helped him to live again. It was a cold and dark winter night when we left the Millennium Theatre once the concert had ended. There was a film crew in situ outside, shooting the latest series of the TV show Derry Girls set in the city. The night, nonetheless, seemed to glisten with possibility. ‘It’s the great search,’ I thought, recalling those writings on Astral Weeks, ‘fuelled by the belief that through these musical and mental processes illumination is attainable.

Or may at least be glimpsed.’ Illumination, a glimpse of the divine, seemed more than abstraction. Maybe, faithful to Lester’s experience, I too had glimpsed something of the divine, without really knowing, like watching a firefly moving in the sky at dawn.

We are an independent media platform dependent on readers’ support. You can make a one-off contribution via Buy Me a Coffee or better still on an ongoing basis through Patreon. Any amount you can afford is really appreciated.