I had second thoughts about boarding a plane to Stockholm to meet Ingmar Bergman twenty-four hours after being diagnosed with a severe bronchitis, possible pneumonia, in the depths of the winter of 2000-2001. But the chance of a rare encounter with the greatest humanist in cinematic history proved irresistible.

Bergman now appears like a colossus among the Lilliputians in our present Netflix-inflected-era of cinema. By the time I met him – Jean-Luc Goddard excepted – he was the last one standing among a golden generation from the dominant art form of the twentieth century. As Gore Vidal put it: ‘The Tenth Muse, as they call the movies in Italy, has driven the other nine right off Parnassus, or off the peak, anyway.’

So, the last of a fine vintage was residing in Stockholm, that Nordic enclave of decency and rigour.

As director (both in film and theatre) and scriptwriter Bergman is almost unsurpassed as a humanist artist in the twentieth century, but he was also unquestionably an autocrat – a quality one might forgive in a director – who could act like a right bastard. Or so it was said. Certainly his relationships with women (of whom in the fashion of a Tudor monarch he married five and divorced four), and the testimony of male colleagues, would suggests he could be quite the unpleasant human being.

When I visited him, I encountered an aged man, but not a paltry thing, devoid of sentimentalism and self-destructive tendencies, notwithstanding unfair attempts to sully his reputation by the Swedish tax authorities in 1976.

This unfortunate episode led to a mental breakdown and a ten-year German exile. In its aftermath, the special prosecutor said that the alleged crime had no legal basis, and that it would be like bringing ‘charges against a person who has stolen his own car, thinking it was someone else’s.’

Revealing, even a society as solidly rational as Sweden’s was inclined to defenestrate its greatest living artist.

Bergman and actress Ingrid Thulin during the production of The Silence, 1963.

Ladies’ Man

Liv Ullman in 1966.

Bergman seems to have been quite the heartbreaker in his time. Although I think men probably hated him more, which he seemed to be clearly aware of. At least some of his lovers did well out of their association, even if he could be merciless about them.

A long-time lover and mother of one of his nine offspring, the Norwegian actress Liv Ullmann used his fantastic script to create the poweful film ‘Faithless’ (2000). It was more his than her own, and she knew it.

His qualities as a martinet are well attested to. Stellan Skarsgård who worked with him and the Danish director Lars Von Trier said that although he thought the latter was probably mentally ill, he considered him, nonetheless, a great person, unlike ‘that not nice guy’ (a.k.a. bastard) Bergman. Sadly, the qualities of greatness are rarely juxtaposed with niceness.

Christopher Hitchens, excluding his worst failure in not opposing the Bush-Blair invasion of Iraq, claimed before his death that he had nothing to be ashamed of, bar a few unforgivable acts with women. Bergman lived much longer and his genius was undimmed, but there were actions for which many in Sweden will never forgive him. I suspect, however, among males of his generation there was a certain sexual jealousy, as well as professional rivalry.

So a distinct singlemindedness did not make for a ‘man’s man,’ but films suffused with such warmth as ‘Wild Strawberries’ (1957), ‘Fanny and Alexander’ (1982) or Smiles of The Summer Night (1955) hardly sprang from the consciousness of a psychopath.

Ultimately, despite a reputation, like Andrei Tarkovsky, for being a difficult bugger, there is an extraordinary humanity to his oeuvre, evident especially in ‘Fanny and Alexander’, along with a contempt for religious fundamentalism and the deliberate infliction of cruelty. That film is a masterpiece of a kind that acts as a building block to civilisation.

I recall viewing it in the old Lighthouse Cinema on Abbey Street in Dublin on its Irish premier in 1982 along with the late Irish film director Kieran Hickey, a big-hearted gay man. Kieran arrived with a strikingly youthful boyfriend, and another Irish film director of international renown (who will remain nameless) in tow. Afterwards in the nearby Palace Bar that well known director was heard to mutter belligerently “The talented bastard.”

Press conference of Ingmar Bergman at The Venice film festival in 1985.

Stockholm Syndrome

So on that flight to Stockholm I was very concerned about my health, but I determined to go nonetheless having secured the elusive appointment with Bergman at the Swedish Film Institute after a lengthy recitation of how I adored his films.

Mercifully and miraculously, the fever and lung condition ceased to trouble me on arrival, perhaps it was the anti-bacterial effect of temperatures fourteen degrees below, or maybe the adrenalin rush of getting out of Dublin and into a new exciting environment such as Stockholm worked the trick. Either way, the cold expelled the demons from my system.

The following day, after a pleasant tour around the so-called Venice of the North, I was feeling chipper and made my way through the unglamorous state-sponsored housing of Stockholm’s immigrant district to the Institute.

Bergman had allocated a half hour of his time, which ran into over an hour. He was both engaged and culturally astute. James Joyce and Samuel Beckett were discussed, the former dismissed, the latter lauded. Although certainly lacking in avuncularity, I did not encounter a numbing coldness in Bergman. On the contrary I discerned a modulated passion, devoid of sentimentality.

He probably sensed he was on his last lap, but it was several years before his final film ‘Saraband’ in 2003. A last, most wintry achievement.

By that time, he explained, he had retired from cinema due to osteoporosis, as his hands could not operate the cameras. The digital age gave him the freedom to create ‘Saraband’ . So he came out of retirement and created a final work of genius.

It is a rare for an artist to produces a great work of art when over the age of seventy. A select list includes: ‘Ran’ (1985) by Akira Kurosawa, Westward-Ho (1983) by Samuel Beckett, containing the immortal pronouncement: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better’; Saul Bellow’s final novel Ravelstein (2000), and the late flowering of Michelangelo of course. Bergman thus belongs in the Sistine chapel of talent undimmed by age.

I would not describe Bergman as emotionally closed when we met. Unlike Samuel Beckett, who I also encountered, he was far from reluctant about talking about his own work. Though hardly modest, he was at least self-critical. Such modesty would have been misplaced in a genius.

The exterior of the building was used by Ingmar Bergman for the bishop’s house in the film Fanny and Alexander (1982).

Relationship with Religion

After retiring as a director in 1982, his script writing came to the fore, earning him many awards. Thus, a screenplay about his parents’ lives ‘The Best Intentions’ (1992) brought a Palm D’Or to its director Bille August. ‘Faithless’, (2000), featuring a character called Bergman, and directed by Liv Ullman was also much garlanded, as was his theatre work in that period.

Above all else there are clear intellectual and humanistic themes evident in his work, often demonstrated in stark terms, but leavened by a comic touch.

Where to start with evaluating this genius? It is worth recalling that his father was a conservative Lutheran pastor under whose authority the young Ingmar was locked up in dark closets for infractions such as wetting himself.

His autobiography Laterna Magica (The Magic Lantern, Chicago 2007) records:

While father preached away in the pulpit and the congregation prayed, sang, or listened. I devoted my interest to the church’s mysterious world of low arches, thick walls, the smell of eternity, the coloured sunlight quivering above the strangest vegetation of medieval paintings and carved figures on ceilings and walls. There was everything that one’s imagination could desire—angels, saints, dragons, prophets, devils, humans…

He also bridled at the testing and homework required in secondary school, and was thus considered a ‘problem child;’ it is striking how many artists are ‘problematic’ to authority figures.

Resistance to authority figures and a deadening Puritanism is obvious in a film such as ‘The Seventh Seal’ (1957), which includes the extraordinary scene of a life or death chess match between the knight played by Max von Sydown and Death played – pronounced evocatively as Döden in Swedish – played by Bengt Ekerot.

There is also a precious understanding that children should be children in ‘Fanny and Alexander’, and we find an acute understanding of pain and death in ‘Cries and Whispers’ (1972). Then we find a chilling grasp in ‘Persona’ (1966) of the abusive relationships between women and men, and women and women, based on inequality, intellect and bargaining power.

Despite his early rejection of religion, Bergman displayed a love of magic and ritual in many of his films; while the first part of ‘Fanny and Alexander’ features a release of warmth in what we assume to be a cold person, but is not entirely so. The idea of time passing and emotional disappointment is beautifully conveyed in ‘Wild Strawberries’, which scales the achievements of the Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu.

And of course there is merriment in parts of Fanny and ‘The Magic Flute’ (1975), and the awful deceptions of love in ‘Summer with Monika’ (1950); and above all in the brilliant romantic comedy ‘Smiles of a Summer Night’ (1955), which was turned into a Broadway musical ‘A Little Night Music’ by Stephen Sondheim in 1973, and which also inspired Woody Allen’s ‘A Midsummer’s Sex Comedy’ (1982).

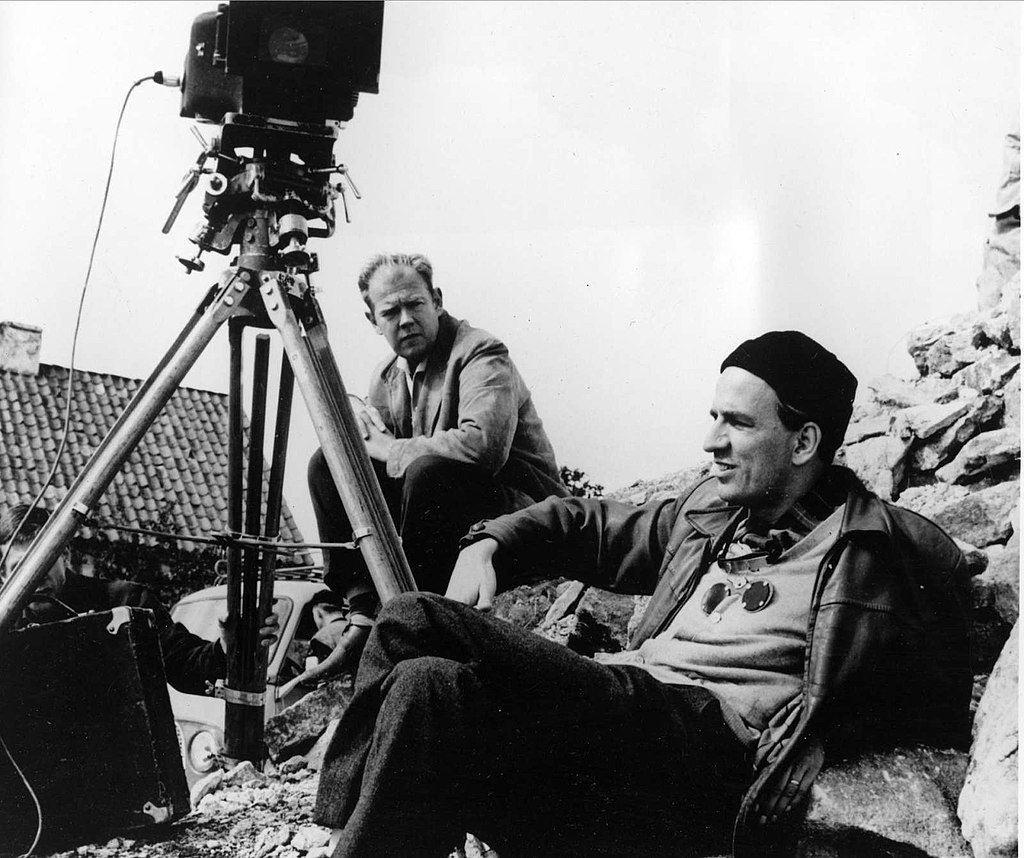

Bergman on the set of ‘Wild Strawberries’ in 1957.

Fårö Away

By the time I met Bergman, he was dividing his time between Stockholm, and a more reclusive existence on the island of Fårö in the Baltic Sea.

Dressed in a duffle jacket and an ordinary pair of jeans he set about recommending various sights to visit in Stockholm and its environs, and spoke at length about Beckett and Tarkovsky who he regarded as a natural successor. He considered Liv Ullmann his greatest muse. Perhaps he considered her the one who got away, given the pair never married, despite having a child together, unlike the other mothers to his other children, all of whom he married.

Victor Sjöström

I recall him also waxing lyrical on the performance of Victor Sjöström – then approaching eighty years of age – in ‘Wild Strawberries’ – which must go down as one the best performances by an aged actor in cinematic history.

After the first hour had elapsed it became clear that I would not be graced by his presence any longer. Genius loves company to quote Ray Charles, but on its own terms, and time was precious.

Bergman was undoubtedly a selfish individual, and an egomaniac, but he was, nonetheless, among the greatest humanist artists of all time.

His work has a lot to say to our own muddled time: that children deserve childhood and not religious intrusion; that fundamentalism of all types is dangerous to civilisation; that bullying can occur between and across genders; that death and plague are omnipresent in the game of life, and that our modern age is precarious and an historical consciousness remains important.