It’s Mother’s Day morning and I am on the brink. Desperate, determined, exhausted and certain all at once. I have passed an eternal night trying to push out a child, with no apparent progress.

I don’t have a midwife gently coaching, or calling the ambulance, as the case may be.

I am freebirthing.

‘Is that like a home birth?’, people would ask, when I told them of my birth plans. ‘Yes, only without a midwife,’ I would say. ‘Oh,’ they would respond; an ‘oh’ loaded with ambiguity. Because, in fairness, it doesn’t sound ideal.

Most Irish women choose to give birth in hospital because they think home birthing with a midwife is a riskier option. This is a view promoted by every medical professional in the country. However, some reading of alternative birth experts soon reveals the best kept secret in the Coombe: a woman’s body is designed to give birth unassisted.

Known as a physiological birth where each biological process activates the next in a delicately balanced sequence, it is the origin of the hypnobirthing image of the unfolding lotus, petal by petal. The most dangerous thing one can do at a birth is interfere with this process.

Modern obstetrics which is based on the ‘active management’ of birth, is the petal plucking inverse of this ideal. Drugs to induce and speed labour and pain medications which stall labour, are standard interventions in normal hospital births. These then lead to ‘emergency interventions,’ such as antibiotics, episiotomies, foreceps and Caesarean sections (c-sections).

In effect, obstetricians are busy ‘saving’ mother and baby from the complications they themselves created.

From the perspective of physiological birth; modern obstetrics is akin to a sexual violation of women. It is predicated on ‘getting the baby out alive’, an approach which traumatizes and damages the long-term health of both mother and child.

Most obstetric staff have never even witnessed a physiological birth. Midwifery training in Ireland takes place in a hospital setting only, and most will have never witnessed a home birth, and could be more accurately called obstetric nurses.

As Irish hospital policy is increasingly determined by insurance liability, where the proof ‘we did all we could,’ is the best defence against malpractice suits, there is a corresponding rise in the national rate of c-sections.

So, in the medical paradigm, which expectant Irish mothers are forced to occupy, for lack of an alternative, where home-birthing is risky, freebirthing would be considered reckless.

And we all know what happens to reckless mothers: They get Tusla called on them.

A HSE homebirth

I applied to the HSE home birth scheme for my first birth in 2018. But the community midwife serving West Kerry had retired one year previously and had yet to be replaced.

There are about twenty community midwives serving the entire country – and the HSE insurance requires that at least two midwives attend each birth. As there is no community element in midwifery colleges in Ireland, our national home-birth scheme relies entirely on midwives who have been trained abroad. Little wonder then that just 0.4 per cent (approximately 280) of births in Ireland occur at home.

So, despite occupying an entirely different health paradigm; the hospital was the only option available to me. And then I discovered freebirthing.

After reading Laura Shanley’s Unassisted Childbirth, which lists the myriad ways that medical intervention causes birth complications, I decided to birth at home, without a midwife.

But with the combination of a long labour, doubtful doulas and a fretting family, fear overtook faith. In the early hours of Little Christmas, we drove from our home on the Dingle peninsula to Tralee hospital, naively thinking we could get checked out, allay our fears and be on our merry way.

We hadn’t accounted for the Hotel California door policy of the Irish maternity ward. Labouring women can check in any time, but security locked doors ensure they cannot leave. ‘For our own good’ presumably.

And there in the belly of the beast, I fell foul of the highly medicalised birth policy, which allows a woman just 18 hours to deliver her baby from the time of her waters breaking before emergency intervention. In the U.K. birthing mothers are given at least 24 hours before ‘emergency deliveries’ are considered.

So, despite the fact that first time births can take up to forty hours to deliver, mine was treated as an emergency and my refusal of syntoconin (a drug to speed up labour) infuriated the obstetrican. The umbilical cord was cut immediately after birth, still pulsing full of blood. The child was pulled from my breast, even as he began to grub for colostrum and taken next door to instead be given a shot of glucose for pacification, as the paediatrician syringed a vial of blood from his tiny veins.

My refusal of ‘precautionary’ antibiotics on the grounds that it would destroy my son’s virgin microbiome precipitated a stand-off in which we were threatened with a court order, the Gardaí and Tusla. The Tusla officer was almost embarrassed, being called to ‘investigate’ and indeed intimidate the only woman on the ward who was breastfeeding.

There followed three arduous nights in hospital in which my son’s sugar and salt levels were monitored, each day bringing new threats to my hopes for a natural beginning to his life: ‘If you don’t get those levels up, we’re going to have to give him formula.’

That was my trauma. Minor compared to most, but it radicalised me, made me an advocate for birthing reform and affirmed my position outside the system. But Life will always buck an affirmed position.

For my second pregnancy I was even more determined to birth at home. But at thirty-six weeks, after a heavy, heart-wrenching bleed, I went for a scan that showed placenta previa, where the placenta is encroaching on the perineum and obstructing the safe exit of the child. Though the child’s head could nudge past, it’s a high risk one, even for a fervent opponent of the system like myself.

So, again I was bound for the belly of the beast and Eirú, my daughter, was delivered by c-section. And I saw the medical maternity machine from the other end of the spectrum. As a birthing mother not wanting intervention, I was treated as a pariah, but as a birthing mother needing intervention, I was treated as a queen. As in this way, I made my peace with these two faces of the Irish medical industry; a merciless machine staffed by heartfelt humans.

But, though tempered, my view was unchanged. Previa affects 0.2% of mothers. And the national rate of c-section is 30% and there is a chasm of accountability between the two figures.

A film looking at the way people give birth in Ireland, the system and how it should change.https://t.co/2ivReYmId1

— Frank Armstrong (@frankarmstrong2) March 30, 2024

Third time lucky

So here we are in 2024, pregnancy number three and we are older and wiser and much less furtive than we were as first time parents. Now we are open about our plans to freebirth. The pregnancy is fully ‘off grid’. I don’t even feel the need to visit the G.P.. My dates are sure. My pregnancy is healthy.

Having gone through the rigorous and ambiguous process of ‘getting signed off’ for a HSE home birth previously, I knew my designation as a geriatric VBAC (meaning a forty-one-year-old vaginal birth after c-section) would eliminate me from the narrow confines of ‘low risk’. So, I spared myself and the child the bother of engaging with a ‘care system’ that would reduce me to such terms.

A doula with a doppler the week before gave me the reassurance I needed that the placenta and baby were in a good position. I’d read the freebirth manual twice over; I was packing shepherd’s purse tincture for post-partum haemorrhage, clary sage and castor oil to stimulate the uterus, chilli tincture for the child’s respiration and I had the numbers of a few good women that I could call for advice in a pinch. Ready as I would ever be.

The bull jumping ceremony of the Hamar tribe in Ethiopia.

The Initiation

To become a mother, a woman must shed aspects of her youthful self that would create chaos for herself and her new child. So Nature, in her infinite wisdom, made birth a rite of passage. An initiation into motherhood.

Initiations are characterised by endurance. Birth is not painful per se – a contracting uterus after birth is usually more painful – though birth ‘complications’ can be very painful indeed, but it is intense – earth-shatteringly, butt-rackingly intense.

The initiate must undertake a journey into the unknown, meet her limits and transcend them. She is shown the insubstantial nature of her persona and must rely on the felt experience of her body and access the instinctual wisdom of her mammalian brain. The two aspects of her self will grapple, the little and the large, the personal and the impersonal taking turns to lead. Her fear will do battle with her trust.

I cannot say for certain that my faith was stronger than my doubt or that my courage prevailed over my fear. For there were times in those eight hours of the most intense pushing sensations, in which every fibre of my being shuddered and squeezed with the effort of expulsion; pushes so magnificent as to be worthy of the crowning glory of a head; only to succeed in squeezing out yet another tiny piece of shit – which my faithful partner faithfully wiped away; the orgasmic foreplay of pre-labour forgotten in the less pretty reality of active labour – that my weakness and doubt did prevail.

Between these surges, I sometimes collapse weak on the bed taking the minutes of reprieve to drift into a semi-conscious nap. But it was no power nap. On the contrary, using the intervals in this way left me ill-prepared for the violence of the surges and less than aware riding them.

In the other times, I breathe and remain alert and rise like a disciple to meet those waves as they roll my body; and those waves I rode. So, on I go through the night like a surfer, catching a few and getting wiped out in others as my strength gives out; my pre-labour thoughts of Macha, the horse goddess, running a marathon in childbirth, gone as I half roll on the bed baying like the cow goddess Boann.

Transferring to a hospital is as inconceivable as it is impossible in my current state in which all that exists is me riding an ocean of sensation.

Sometime, about half-way through the storm; Diarmuid drills a hook into the ceiling and hangs an extension cord from it that I could bear down on it.

Image: Nicky Manosalva

Alien Cow Goddess

Eight hours of eternity passed like this. Me and Doubt and Faith and Baby and the rest of the Gang going up and down. Diarmuid keeps vigil on the periphery. The children sleep soundly next door.

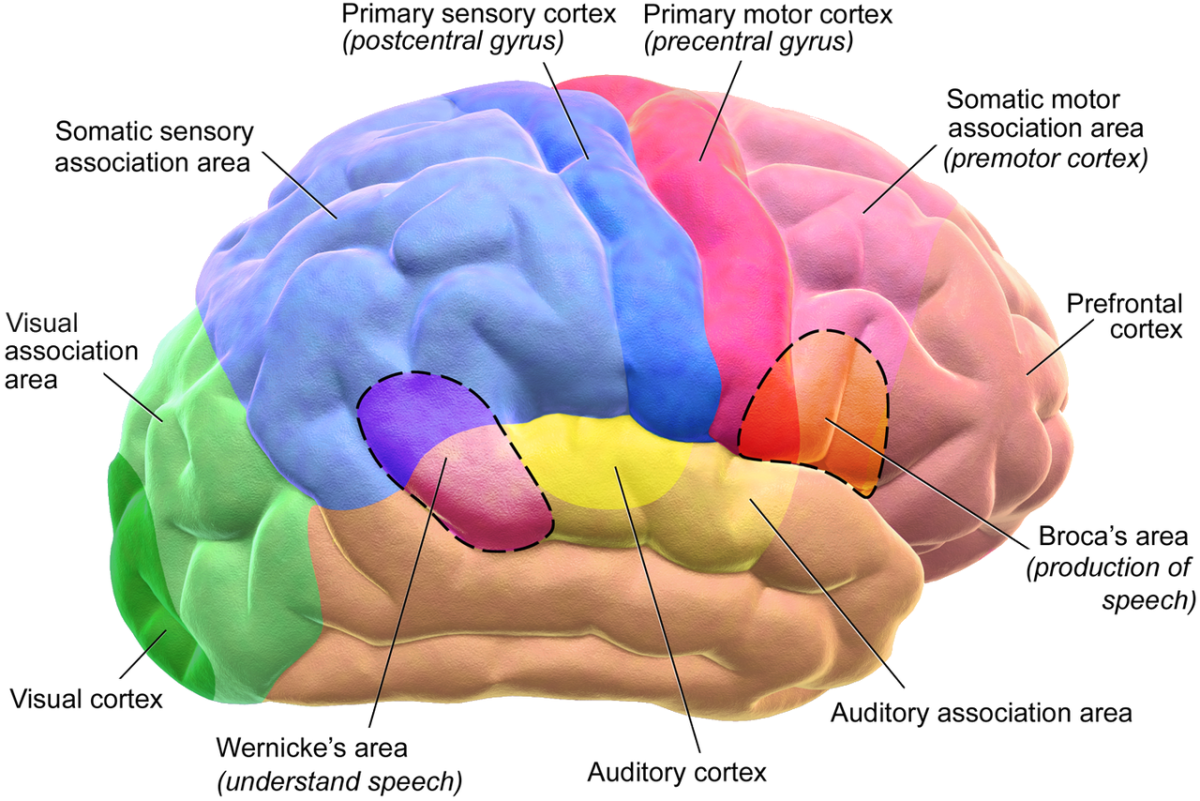

Then there is birdsong and dawn light. Morning arrives but the baby does not. From the frontal cortex of my brain comes the thought (for I now occupy the recesses) occurs: ‘I don’t want the children to witness their mother as an alien cow goddess’.

The children wake and Diarmuid goes out to them. I stay in the room, baying through the surges and I hear Eiru start to cry at the strangeness of the sound.

My instinct says there is nothing wrong, but here I am again in a labour that is taking ages. Patience. Tenacity. Endurance. The words rise from my subconscious as guidance. But my frontal cortex says: ‘Diarmuid, It’s not progressing, we have to call someone.’ Something for him to do. He’s on it.

I emerge from the bedroom to reassure my daughter, my body a boiling ocean.

‘Mammy when I woke I thought there was a cow in the room,’ my son says. Amused, I feel the wave building inside me again. I hug my anxious daughter quickly, ‘Mammy’s good, baby will come soon;’ as the wave towers over and in me, about to break. I step out of her embrace and into the toilet, close the door, sit on the bowl in a sequence of seconds.

And the wave breaks.

Only this time, unlike the hundreds or thousands of other times throughout the night, the wave carries a little body in it and pushes it all the way down the birth canal.

‘Diarmuid’ I croak, with jubilation and anxiety and blood all mixed. And he is there. ‘Oh thank God, the head.’ And he calls out to our six-year-old: ‘Uisne, take your sister into the neighbours, I’ll come soon’.

‘Dig deep, one more push,’ he says, not knowing that I am being dug, I am being pushed. But I follow his instruction anyway, like a robot. And a big slippery child comes out. And we catch him between us.

There is blood; looks like a lot of blood. How much is too much? We don’t know. But seven drops of shepherd’s purse tincture under the tongue should be sufficient. Is he breathing? I suck mucous from his nose. Yes, he is. Oh, sweet slippery baby. Diarmuid tries to carry me to the couch, but the domesticated mammal bridles at the prospect of getting blood on the couch. So, I sit in a pool of blood on the floor. Looking every inch the warrior. Bruised and weeping, utterly spent and victorious.

We haven’t been out in public yet. We are resting. I am writing. We are content. I tend to his umbilical cord myself. I treat my hemorrhoids with frankincense and aloe vera and look at my cervix with a hand mirror and great fascination. I am my own healer, calling on fellow warriors for advice.

He has not been outside yet, felt the spring on his silken skin. But I will not rush him, I wish for his separation to be as gentle as possible.

Some authority that had been taken from me at Uisne’s birth by coercion, at Eiru’s birth by fate. It has been restored by this home birth; this freebirth.

Maternity Rights

I represent a growing number of Irish women who have an ‘alternative’ approach to health. My faith in modern medicine is limited to its functionality in diagnostics, bone setting and some emergency interventions. That’s it. I don’t believe it has any real role in solving chronic illness, which cancer would be, and I most certainly don’t think it has any role to play in 99% of births.

From this worldview then, giving birth at home is a ‘no-brainer’, except that it’s also a ‘no goer’, for many Irish women, who, either through age or some perceived health issue, (i.e. low iron, vegetarian diet or high blood sugar) or geographical reasons, do not have access to the very limited HSE home birth service.

In 2008, community (home birth) midwives were compelled to sign very restrictive memorandum of understanding with the health service. Midwives became obliged to transfer birthing women to the hospital in scenarios previously considered normal, such as heightened blood pressure or a delay in labour, or risk losing their licenses to practice.

The U.K.-based Private Midwives Ireland operate under a slightly less restrictive insurance requirements, but the cost of €6,500 to €10,000 precludes many women.

So, into the barbarous hospitals we go. Or not. Freebirth is our bright shining alternative.

The highly medicalised maternity model in Ireland is compelling Irish women to give birth unassisted by midwives at home. And though this may sound like a dangerous scenario to the uneducated; the experience has been both empowering and healing for a growing number of Irish women, many of whom are now sharing their stories on social media.

Motor and Sensory Regions of the Cerebral Cortex.

Instinctual Mammalian Brain

The physiological unfolding of birth requires that a woman relax completely in order to occupy the instinctual mammalian brain that governs the birthing process. Anything that draws her into the frontal cortex is discouraged in this non-intervention, best practice birthing model. Hospitals then, are exactly opposite to the optimal environment for a birthing mother. This reality has been recognized in many European countries such as the Netherlands, which has an extensive national home birth service and birthing centres.

Ideally, Irish mothers would be attended by experienced midwives who did not have to operate under such punitive criteria and the threat of losing their licences. But in the absence of this, giving birth at home under her own authority is one of the most liberating and empowering things a woman can do. Finally, I can testify to this.

Life contrives to give us what we need. In the decimation of our home birth service, there is an opportunity for us to step into the gap ourselves alone. The rewards are great and many. And perhaps if enough of us step into that breach, the country’s health care professionals will be compelled to answer the call for maternity reform and give us the support in our own homes that we deserve.

Follow Siobhán de Paor’s blog: http://insideoutpost.ie/