Une Charogne (1859) is among the most important poems of the 19th century, containing all of its author’s ground-breaking aesthetic. Our own aesthetically challenged century could learn a lot from it, in terms of the aesthetic of rupture, spleen and discord.

It is Baudelaire’s response, in a sense, to the early Romantics, such as John Keats for example, and particularly concerning notions of beauty. Baudelaire, like Mary Shelley and Shakespeare before her, found more engagement in what could be described as the dark horror of existence, which had always existed in literature, particularly in writers such as Dante Alighieri, in whose work Dame Francis Yates saw the keys, or genesis, of the Gothic novel: in particular in the last Canto of the Inferno when Count Ugolino is forced by starvation to eat his sons locked away in a tower. However, Baudelaire’s genius was to take such an aesthetic into the everyday. In this this way he was a true revolutionary and visionary.

Count Ugolino and his sons in their cell, as painted by William Blake circa 1826.

Une Charogne is the perfect example of his aesthetic. The poet starts off describing a carcass which he has seen rotting on his way home, and which he associates with a former love which he felt for his girlfriend. The reader, however, is only made aware of this in the very last verse of the poem. The remarkable contrast of topics is so unexpected that even one-hundred-and-sixty-years on the poem continues to shock.

The poem, typically, follows the genre of memento mori, Baudelaire’s originality lies, however, in applying what were rather banal motifs associated with death – such as skulls placed alongside everyday fare like fruit and flowers – and then to insert affairs of the flesh, and, of course, the heart.

Only readers who have experienced real heartbreak themselves, what the Ancient Greeks described as the Orphic mysteries, will have any real appreciation of the fantastical act of catharsis that is taking place, how the poet wonderfully evokes his former passion for a beloved, and then inverts Love with its counterpart Hate; thus upturning the apple cart of feelings for the beloved which have been transformed into their opposite; diabolical hatred and disgust; perhaps more so for himself, for being duped by such feelings in the first place!

As indicated, anyone who has been in Love and who has then lost – inevitably harbouring a sense of betrayal – will recognise, and feel, the powerful emotions driving the poem forward. The poet’s dedication and craft at the description of the whole process continue to inspire awe.

Three Studies for a Portrait of Henrietta Moraes, by Francis Bacon,1963.

Francis Bacon Interviews

Regarding my transversion, I was helped enormously by using the interviews conducted by David Sylvester with the twentieth century British painter Francis Bacon. Bacon was a keen reader of Baudelaire, and one who followed the French poet’s dramatic overhaul of the Romantic spirit. One only has to consider Bacon’s entire corpus of imagery, the violent palette of colour, the decomposing matter of flesh, and the ‘smoky bacon’ of decomposing Love!

I find that this unique aesthetic contradicts directly the flimsy narrative of many contemporary literary journals which are marred by politically correct censorship; the overwhelming and ever-present narrative of all-inclusivity and sensitivity to Others that has now reached idiotic proportions.

What do I mean by that? Take for example the narrative of Une Charogne below. Anybody reading the poem with a half a brain will understand there is a very definite mask wearing taking place on the part of the poet. The diabolical humour is just that, a very nasty joke. But one which is very human.

When one has been jilted the immediate response is to seek revenge. Exact some hate! This is simply being human, and to deny the presence of this impulse is simply perverse. All is fair in love and war. A person who has betrayed you with another having vowed to love you forever is now in the arms of another.

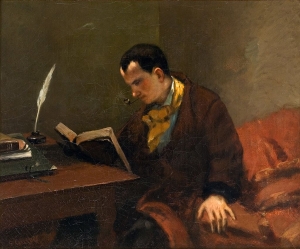

Portrait of Charles Baudelaire by Gustave Courbet (1848).

Fail Again

There is, I would say, no greater pain on this Earth than the agony of abandonment. It is the hardest possible task for any human being to accept graciously that loss, and then to move on. It reflects the instruction of Samuel Beckett in Worstward-Ho: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.’

Life onwards will be mere monochrome. A travesty in a sense. This is the exact sentiment that lies behind Baudelaire’s Une Charogne. The poet is damned, damned by the Other. And so he will exact his revenge. The poet finds it in the poem, alone, in its very composition.

I would liken this Art to extracting puss. It is an act of catharsis. Again, a very Greek notion. Francis Bacon was also a great fan of the Ancient Greeks, like Baudelaire before him.

I have made the point repeatedly: if there is not a little poison in the well there is no sweetness to the water. I have met all too many high-minded moralists who plead constantly for whatever Other is currently in fashion.

These latter-day saints among the chattering classes are hypocrites, who sanctimoniously bottle up their resentments. I have been a witness to a deformed humanity spurting out in the most toxic manner imaginable. Believe me, it is not a pretty sight! — Hypocrite lecteur, — mon semblable, — mon frère! (— Hypocritish reader, — my fellow, — my brother!)

The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan.

Broken Word

On the philosophical plane the poet has completely sublimated Friedrich Hegel’s (1871-1831) dialectic of the Master and Servant. To speak in the terms of Baudelaire’s countryman Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) – of a different generation but observing an unaltered humanity – he is killing symbolically the Other in the world of the Real. This for Lacan, as for the poet, is entirely symbolic.

Baudrillard – perhaps the most Baudelairean of late twentieth century French thinkers – was to make of this his unique discourse point. He believed that we had lost our capacity for creating metaphor, so enamoured were we by the hyperreal; that is to say the literality of living we now observe in a mediated age where news is constant, and so ever-present. The Hegelian Now repeated ad infinitum is a poet’s nightmare. This explains why we are living in a period of atrocious, purely confessional poetry. The so- called ‘Spoken Word’ where the Now is Ever Present!

I AM

The spoken word speaks – BEING poetry itself! Such is the utter fallacy.

This is the poetry of idiots.

If you do not kill your enemy symbolically, you will never kill him. Such is the Real. Not reality, but the symbolically Real, which for a poet IS the only reality.

Have you ever considered where Populist monsters spring from?

Take a leaf out of Baudelaire’s black book, write your words in Hate, as much as Love. Be the totality that is You. And you will be a better artist, and Human, for it.

XXIX.- UNE CHAROGNE

Rappelez -vous l’objet que nous vîmes, mon âme,

Ce beau matin d’été si doux :

Au detour d’un sentier une charogne infâme

Sur un lit semé de cailloux,

Les jambes en l’air, comme une femme lubrique,

Brûlante et suant les poisons,

Ouvrant d’une façon nonchalante et cynique

Son ventre plein d’exhalaisons.

Le soleil rayonnait sur cette pourriture,

Comme afin de la cuire à point,

Et de rendre au centuple à la grande Nature

Tout ce qu’ensemble elle avait joint ;

Et le ciel regardait la carcasse superbe

Comme une fleur s’épanouir.

La puanteur était si forte, que sur l’herbe

Vous crûtes vous évanouir.

Les mouches bourdonnaient sur se ventre putride,

D’où sortaient de noirs bataillons

Des larves, qui coulaient comme un épais liquide

Le long de ce vivants haillons.

Tout cela descendait, montait comme un vague,

Ou s’élançait en pétillant;

On eût dit que le corps, enflé d’un souffle vague,

Vivait en se multipliant.

Et ce monde rendait une étrange musique,

Comme l’eau courante et le vent,

Ou le grain qu’un vanneur d’un mouvement rythmique

Agite et tourne dans son van.

Les formes s’effaçaient et n’étaient plus qu’un rêve,

Une ébauche lente à venir,

Sur la toile oubliée, et que l’artiste achève

Seulement par le souvenir.

Derrière les rochers une chienne inquiète

Nous regardait d’un oeil fâché,

Épiant le moment de reprendre au squelette

Le morceau qu’elle avait lâché.

Et pourtant vous serez semblabe à cette ordure,

A cette horrible infection,

Etoile de mes yeux, soleil de ma nature,

Vous, mon ange et ma passion !

Oui ! telle vous serez, ô la reine des graces,

Après les derniers sacrements,

Quand vous irez, sous l’herbe et les floraisons grasses,

Moisir parmi les ossements.

Alors, ô ma beauté ! dites à la vermine

Qui vous mangera de baisers,

Que j’ai gardé la forme et l’essence divine

Des mes amours décomposés !

XXXIX. – The Exquisite Cadaver

Remember the ideal object which you discovered~

That beautiful summer morning, Dear soul:

By way of the path where you found that exquisite

Cadaver lying on a bed of pebbles,

Her legs in the air, like some old tart,

Burning and stewing in poisons,

Her belly slit, almost nonchalantly,

Pouring forth all manner of noxious gasses.

The sun burns down on the decomposing

Body, as if searing a steak,

Rendering back a hundred- fold to Mother Nature,

What she herself had first conjoined.

And the sky looks upon the superb carcass

As it would upon a flower of Evil,

The rigor mortis encroaching to such a point

That the very earth around it has been scorched.

Great Blue Bottles swarm in convoys,

Buzzing out of the gaping cave, Cyclopean…

While a treacle of feasting larvae thickly drip,

Making of the stain a macabre Persian carpet.

The process of decomposition rose before me,

Falling in waves, and which I perceived in a kind of

Pointillism, so that, wave-borne,

The corpse seemed to come alive and multiply before me!

This alternate universe was announced in atonal chords,

And hit me with all the fever of a jungle humidity,

Or, like the sporadic grains, scattered by a winnower,

Whose rhythmic movements spun me in a dervish.

The effaced shapes and forms were as if but a dream

From a preliminary sketch, slow to arrive,

And which the artist, not being able to rely on memory,

Had then to resort to the magnetism of specific photographs.

Behind the rocks an unnerved dog

Looked at us both with a ravenous eye,

Trying to deduce the auspicious minute

When he could rip apart some rotting flesh from the bones.

And yet, You now would appear to be not so dissimilar to this horror,

This putrid infection,

At one time Star de mes yeux,

You my one time, all consuming passion!

Yes! After the last rites have long ago been pronounced upon us,

O You, my once graceful Queen,

When will you now, in your own time,

Wallow with these bones upon the grass?

So, my great Beauty! Whisper then to the vermin

How you will cherish their kisses,

While I guard for eternity this sublime image,

Of all of our decomposing Love.

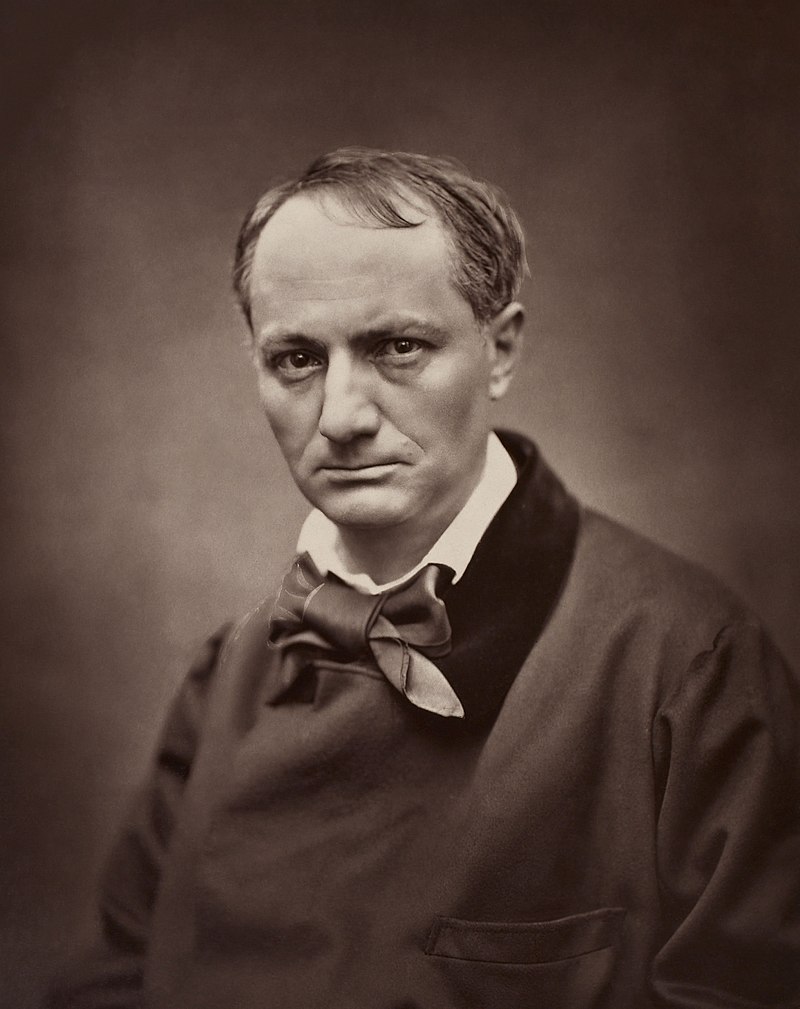

Feature Image: Charles Baudelaire by Étienne Carjat, 1863