In 1960 when I was seven, before TV, Radio Éireann was our window on the worId. I understood the gist of rumblings on the news over breakfast in the kitchen. The Congo. It used to be called the Belgian Congo now it was just the Congo. My father intimated, buttering a piece of toast at the kitchen table before whacking the top off a boiled egg with the knife, that the Belgians were still sticking their noses in.

His remark was to no one in particular, almost sotto voce. Over the years on matters of the Irish nation you’d be listening out a long time without a single revelation concerning his party-political pedigree. Years after his passing, my adult siblings had no idea was he a de Valera man or a Michael Collins man.

On global affairs he was only marginally more loquacious. Maybe, I inferred in this case, the Belgians were the Congo’s version of the English only not as big. Over the radio newly familiar names resonated across our kitchen. Patrice Lamumba- he had something to do with it. Lamumba was the new man in charge over there and he didn’t want any English or Belgians or outsiders of any sort coming over and interfering in the newly decolonized country. That seemed fair to me.

Katanga, that was another new name on the news. It was a province, like Leinster. They wanted to rule themselves; the Katangans didn’t want Lamumba running things at all. Tshombe was the big man in Katanga. Congo, Lamumba, Katanga, Tshombe; distant names were rendered close by the radio, formed part of the backdrop to the morning kettle steaming, bobbing eggs boiling in a pot on the cooker and toast smoking aromatically under the grill.

Balubas

Irish lads were to be sent off with other U.N. troops to keep the peace; stop the Katangans and Lumunba’s army from getting stuck into each other. The Baluba tribe in Katanga, it turns out, were also very unhappy about the whole situation – so we heard another new name on the radio. Baluba.

Two Irish battalions were being dispatched. I hadn’t a clue what a battalion was only it was a lot. My father took me into town on the 13 bus to see them off.

Our journey started at the terminus behind Beechwood Avenue Church, officially the Church of the Holy Name. I loved hopping onto the open-backed bus, straight up the narrow stairway to the front seat at the top, to wait a few minutes for the busmen to finish their cigarettes and start her up to head into town via Ranelagh, Appian Way, Leeson Street, Stephen’s Green and Dawson Street.

The soldiers’ journey from Ireland to the Congo started with a march down O’Connell Street (picture above) to mark this moment of significance in our national life. After marching, the troops were to be loaded onto gigantic transport planes along with armoured carriers at Baldonnel airfield outside Dublin.

We got off the bus on Dawson Street near the Hibernian Hotel and joined the masses walking along Westmoreland Street, kept going and got across O’Connell bridge. Near Daniel O’Connell’s statue, in the middle of the street where cars usually parked, up toward Clery’s department store, my father was trying to squeeze me up to the front row but he couldn’t get by with me so we sandwiched in as best we could, he lifting me up from time to time.

Throngs crammed the streets and footpaths to gawk or cheer the column of soldiers marching by, their hob-nailed boots clattering along with a metallic after-sound. A man said the Garda Band had led the way with big brass instruments but we missed it. We couldn’t get near the GPO; people were jammed ten thick or more. Dignitaries, someone said, were on a platform in front of the GPO reviewing the troops.

A woman said there were Guards and soldiers holding the crowds back. Some lads had climbed up near the top of lampposts – to the part where two iron handles stuck out near the light. How they got up there was something of a marvel; I envied them the birds-eye view.

“They’ll roast in them outfits,” one woman said presciently. (It transpired that the troops were woefully unprepared – with not enough gear or the wrong gear, wooly dark green uniforms that would hamper them in the ferocious equatorial heat).

A man asked if they’re walking all the way to Africa and people laughed. Another wag said they’d be getting a free trip in a Yankee plane blessed by his Holiness John Charles McQuaid, a reference to the fearsome Archbishop of Dublin.

Archbishop John Charles McQuaid (1895-1973)

I joined my father in frowning at that bit of disrespect for the lofty bishop while wondering did we not have our own planes. I was a bit confused by the parade, unsure what the Army was doing parading down the middle of the street – though I got a look in between the adults in grey coats at bands of red-faced soldiers bunched together swinging their arms, stomping their way down O’Connell Street with intent. There were swarms of them – hundreds- and they had guns over their shoulders, real guns. I had never seen real guns before, never mind so many.

It was a new thing for Irish soldiers to be sent off into the middle of an African civil war. The last civil war any Irishman took part in was our very own one in 1922 and the contemporary national army, such as it was, hadn’t seen combat of any kind. But they were dispatched off anyway because everyone knew Irish people were respected the world over.

"Successive migrations culminate in a return to the home ground of Sligo, where memories mingle with national conversations amidst a preternatural tristesse."https://t.co/0ovfReOeha@broadsheet_ie @modelsligo @sligotourism @PointRosses @BenPantrey @IlsaCarter1 @WaldronDara

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) December 9, 2021

Irish Army Jokes

As a boy, I only heard of the Irish Army in jokes – passing around the one gun like a shared cigarette; halting maneuvers in the Furry Glen because the missus forgot to pack the sandwiches.

That we were Irish I knew, but there was an accompanying feeling that Ireland was barely a country. For decades government ministers made an art of going on the radio insisting that nothing could be done about anything ailing the nation: dire poverty; a shite economy; high unemployment; mass emigration.

Sure Ireland is a small country, they’d say, the message being we should not get our hopes up about ever approaching England’s standard of living, never mind row in with the U.N.

We’re a small country – for years that was the party-political consensus for upholding and excusing a mediocre status quo. We were scarcely a country so every family, including ours, had relatives who had been forced to climb aboard trains, boats or planes, to England, America or as far away as Australia. American wakes they used call the send-off parties for emigrants in towns and villages across the country.

The failure of the #JustSociety movement within #FineGael was a turning point in Irish history. David Langwallner recalls the contradictory career of Declan Costello.https://t.co/RdNsjfXqJX@broadsheet_ie @ConorBlenner @vincentbrowne @LumberBob @KevinHIpoet1967 @liamherrick

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) May 11, 2020

UN Membership

Despite being underdeveloped, Ireland the fledgling republic had joined the U.N. at the end of 1955 just like a proper country. England had nothing got to do with it this time. The troop deployment bypassed England and the uncomfortable fact of our complete economic dependence on trade with and emigration to England.

This was U.N.-led, strictly international. Our soldiers representing the U.N. were to wear blue helmets. I had a plastic replica of a blue helmet for playing war down the end of the back garden with a bit of rifle-shaped ash.

Though I couldn’t know it, this was a big moment in the emergence of Ireland into nationhood. As relatively new members of the U.N., we were taking on an international commitment, helping out in a fight not of our making.

For my father among the many who turned out, to go and bear witness in O’Connell Street must have been important. He was born in 1906 into the last throes of the British empire in Ireland, bore witness to the civil war as a teenager.

To have me along was to teach me about Ireland, to affirm that we had our own place among the nations of the world. To the legions of gallant nuns and priests that routinely went off to Africa on the missions to spread the one true faith, we could now add battalions of our very own troops.

Outings with my father for big occasions were rendered all the more significant by their rarity. He was distant though affirming and not lacking in affection for his offspring; unquestioned Lord of the household, ministered to and royally fed by my mother, who mediated and did what she could to prevent occasional eruptions of his anger, though it simmered like a bubbling stew more often than exploded.

Always impeccably dressed, his black brogues shined to a sheen, he was not around much during a work week, just one evening and week-ends.

Weekday Routine

The family just got on with the weekday routine, ended the day listening to Radio Éireann, later it would be watching American TV shows on Telefís Éireann.

When it arrived into the house, my mother thought the TV was no harm, a bit of diversion. My father worried quietly to her that we would get notions from American rubbish like the Donna Reed show with its idealized portrayal of privileged, prosperous suburbia. Luckily for me, cowboys like Bonanza were fine all around.

Appointed County Manager of Meath, adjacent to Dublin, in 1959 he had moved the family from Sligo where he had been manager to 42 Merton Road in Dublin’s Rathmines, down the road from our grandparents Joseph and Margaret Hynes of 72 Cowper Road.

Commonly, houses were given names – Ivydeane, Cospicua. As we were moving in a man came to paint the name on two concrete pillars by the front gate, black Gaelic lettering on a white painted background – Dún Mhuire, the fort of Mary.

I suspect my mother was the instigator but it seemed natural enough. We were a Catholic household in a Gaelic Catholic culture. Clear but unspoken messages were conveyed to me – nobody sat me down to declare it explicitly – that being Irish and under the auspices of a dominant church whose parish Mass we attended faithfully every week along with crowds of our neighbors, offered a form of protection, a kind of psychic immunity, from the seeping depravity of England.

People in England, unsanctioned, could get a divorce and skip Mass if they were Catholics or not even attend church at all if they were Protestant. The English were more likely than the Irish to be in danger of falling off the cliff edge we all traverse that overlooks the fires of hell.

The example of Matt Talbot's piety was used by the Irish Catholic Church in inculcate subservience as the downtrodden were told to await their reward in heaven.https://t.co/8uOS8DgHKe@broadsheet_ie @vincentbrowne @fotoole @connolly16frank @gemmadunleavy1 @AlanGilsenan1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 20, 2021

Middle Class Respectability

My father had landed us squarely in the emerging professional middle class respectability of 1960’s Dublin, my siblings and I in the best schools. Gifted with brains he had forged his own road, starting off as a lowly clerk in the Port and Docks Board in the Custom House, going to night school in Rathmines Tech to qualify as an accountant.

His big break into the civil service as County Secretary in Kildare came after winning the 1938 Gardener Gold Medal for attaining first place in Ireland in accountancy subjects – I still have the medal. He progressed from County Secretary to an appointment as County Manager of Sligo, a place I still love deeply having been born there, then Meath.

Throughout the 1960’s, unprecedented in those days, he commuted along country roads to Navan, the County seat, taking the guts of an hour to get there. Nowadays, thanks to urban sprawl, Navan is a dormitory suburb of the capital.

Throughout the 1960’s he would stay one or two nights a week at the Headford Arms hotel in Kells, “the Manager” becoming a well-known local fixture. We had no idea what his life there was like. Instead of watching TV in the bosom of his family he would, no doubt, be in the hotel bar nursing a pint or a snifter, getting the full Irish served up for his breakfast of a morning before driving over to the town hall in Navan.

I remember precious little dinner table conversation about his work. Meath had the richest grassland in the country – cattle would be moved from the West to fatten them for export, we were told. Sure, wasn’t Irish beef the envy of the world? The inference being that it was a more prestigious County to manage than Sligo.

He would arrive home on Wednesdays and on Fridays with a prime side of beef for the Sunday roast, set aside by the butcher especially for the Manager. At Christmas, he would land home with seasonal fruitcake, the kind it takes ages to make with marzipan and white frosted icing to look like snow courtesy of the nuns who ran the hospital. There was never a question, let alone a debate, about whether he should be home more often.

Though absent a lot, he seemed no more distant than the fathers of my friends who were always at home. That was the way things were; the mothers were warm, the fathers diffident, to be addressed formally. Without exception my pals’ fathers were cut from the same cloth. Like my own, most of them were not native Dubliners but were making it in Dublin.

Entrepreneurs, lawyers and civil servants, they had roots in rural Ireland, including rugged Western counties like Mayo and Kerry. They wore greatcoats and sported hats, didn’t smile much and enquired how we were doing in school, thinly disguising a suspicion that there was too much playacting going on and not enough knuckling down to study.

A weekend stayover in a small caravan in Donabate North of Dublin by the perpetually grey-clouded seaside – a treat hosted by my mate’s old man for a couple of pals – involved a degree of tension as the ogre-like father complained crankily about the poor quality of the boiled egg served up by his son at breakfast, while the other guest boy and I stifled tense giggles behind the curtain drawn across the caravan.

We were accustomed to our eggs and toast or cornflakes being served up by our mothers; we weren’t called upon to service our fathers. We surely didn’t envy our mate his role as butler to his old man. Shortly after breakfast, relieved, stepping out the caravan door into the morning wind, we scarpered and stayed gone for most of the day.

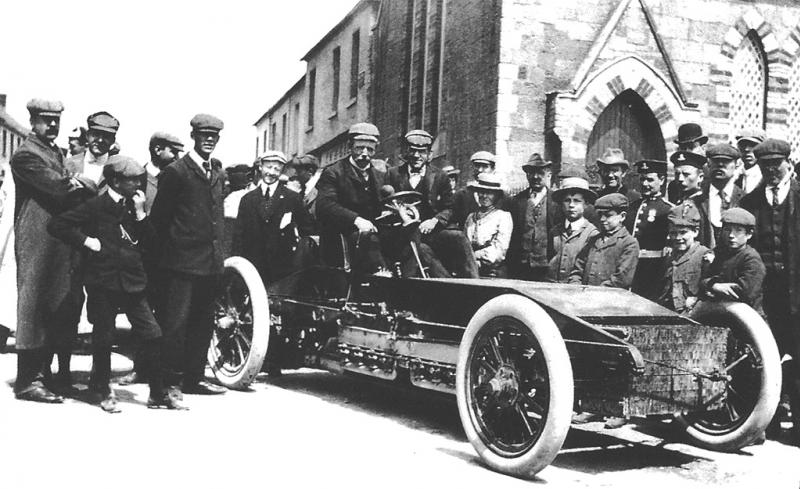

1903 Gordon Bennett Trophy. Athy. Alexander Winton in the Winton Bullet 2.

Athy

It was far from the middle class that my father was reared. He was the seventh of nine to be born in a single room in a one-up-one-down two roomed place, 15 Leinster Street, Athy, Southwest of Dublin in County Kildare, for years a British garrison town where the grand canal from Dublin meets the river Barrow.

My grandfather Michael was a carpenter employed as casual labor in a local factory while my grandmother, a Doyle, labored at home, trying to manage the scarcity of necessities including food and shoes, her home caught in abject poverty.

As an adult, I stood in the claustrophobic upstairs room with my Aunt Patricia and two cousins, one who had bought the place, another who grew up and still lived in Athy. You couldn’t swing a cat in the place.

We cousins shared awed glances as my devout aunt Patricia sprinkled holy water about in honor of her parents. “They were great people, God bless them,” she said as the hair raised along my arms.

A cousin recalled a story his mother – another aunt of mine – had told once about remembering as a girl a visit from a priest who offered a blessing to the household – perhaps someone had been newly born or more likely was very ill as a clerical visit would have been rare to a poverty stricken household.

Protocol dictated that the priest be offered money when leaving, money he had no hesitation in accepting despite the blindingly obvious. He was pocketing the last note and bits and pieces of coins from the household cash tin. The little girl looked on knowing they would miss a meal as the priest stuffed the note and coins into his pocket on his way out the door. Such callous treatment would have been the norm; people were “read out” from the pulpit at mass, poor families shamed as donation amounts were publicly announced by the priest.

“I’m going places.”

There’s a photo – a family portrait (see featured image above) – grandfather looks resigned, grandmother holds a vacant stare; to me they appear defeated. A sheet hangs precariously forming a partial backdrop to the scene. One of the standing elder sisters rests her arm on my father’s shoulder who sits in the center with arms crossed – twelve years old maybe- as he beholds the camera with a confident look as if to say, “I’m going places.”

Indeed, he was and he did. But growing up we knew little of his roots or the road he had travelled from poverty to the middle class. I had an inkling, a feeling that he felt he had escaped, broken free of Athy, and wanted to leave all that behind him.

For years I never knew how many siblings he actually had. We had lots of contact with my mother’s family – I knew all of my cousins on her side.

Silence enveloped the partial story emerging about our Kildare roots. He was close with Patricia in Dublin and her husband John O’Brien of Kimmage Road West, a gentle uncle to us who, smoking Sweet Aftons, held court in their dining room at the top of a large table squeezed into the room, with barely enough space for chairs and a sideboard.

My hospitable aunt doled out scaling tea, sandwiches and fruitcake. We grew up connected to our O’Brien cousins. Visits from them or my mother’s family were occasions of joy and celebration, especially the Christmas night gathering around our piano played by my aunt Ita and lubricated by my father as barman, conductor and on rare occasion warbler in chief.

River Barrow, Athy.

Kildare Connection

The Kildare connection though was opaque. As a boy, I remember from time to time – once or twice a year – my mother and father would get all dolled up and go off for a Sunday drive to Athy.

No account of their day would later be offered. As an adult, I learned that one of the nine siblings had been institutionalized – but where, more to the point why? Were they put in the county home or mental hospital? We never knew.

As children we had overheard whispers. The lore I picked up as an adult was that one sister had unspecified mental health issues but was really put away for falling in love with a British soldier. That didn’t add up. Such romance would hardly have been an aberration in a garrison town, surely?

Despite emerging Home Rule and fledgling republican movements Athy had, per capita, one of the highest rates of young Irishmen volunteering themselves into the British army for the great war of 1914 – 1918.

For the survivors, participation would end up placing them on the wrong side of Irish history. Whether generally tolerated or frowned upon, surely at least a few local young women were forming liaisons with working class squaddies in barracks in the town. Or perhaps the very presence of soldiers billeted in the town lends plausibility to the narrative I received – Irish families clamped down on liaising with British troops, even locals. To this day, a blank canvas remains where that story should be.

In the first of two reviews, Frank Armstrong revisits ‘the fulcrum on which the intellectual foundations of Irish society moved – slowly, but irrevocably.’https://t.co/KoU3AnPLUx@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @paddycosgrave @FourCourtsPress @fallon_donal @corourke91 @AlanGilsenan1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) June 7, 2022

Ardagh Chalice

In Dublin, rare paternal expeditions are preserved to me as wisps of memory, incomplete fragments encased in my mind like the gold ornaments in the glass cases of the archeology section of the National Museum in Kildare Street, where he took me and my sister once or twice when we were eight or nine to see the Ardagh Chalice.

Some young lad dug it up out of the ground over a hundred years ago, he said. I was thinking I would have held on to it if I were him, or maybe flogged it for a new bicycle. At least once he dragged us around the National Gallery, frog marched us past white marble sculptures on plinths to a gallery beyond to eyeball the Jack B. Yeats paintings.

Jack B. and his more famous brother the poet had Sligo connections, developed a love of the county while spending youthful time with relatives there. Jack had painted Memory Harbour in Rosses Point and was known as the painter who chronicled the emergence of Ireland into nationhood, representing Sligo fishermen going about their hard labor as “men of destiny.”

As County Manager, my father had walked behind the painter and Yeats family members in the procession to reinter the remains of W.B. Yeats in the churchyard at Drumcliff. Whether on approaching our pre-teen years we balked or he abandoned the cultural outings based on a sense of having completed our cultural education or maybe felt it a waste of his time “casting pearls before swine” was never clear.

Ben Pantrey discusses the elusive quality of memory in the Jack B. Yeats exhibition running in the National Gallery of Ireland with co-curator Donal Maguire.https://t.co/J8KVzr0XdI@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @IlsaCarter1 @danieleidiniph1 @NGIreland @ArtsOverBorders

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) October 11, 2021

Impromptu Visit

The blank page of his family narrative dramatically came alive in three dimensions one routine winter early evening enshrouded in the usual darkness and damp. I was around ten, waiting for my mother to dish up the tea when she, my sister and I were stunned into incredulity, the lot of witnesses.

I answered a ring at the door to find an uncle from Kildare, brother of my father, smilingly arriving for an impromptu visit. The doorway banter drew my mother from out of the kitchen. She welcomed him in officially and directed me to sit with him in the living room to the left off the hall while she improvised a pot of tea and a few of her prized home-made sweet buns.

The brother, a bit disheveled, sat in front of the fire in one of two chairs with the red covers; asked me how was school going, wasn’t completely sure who he was looking at, not distinguishing me one hundred percent from my older brothers.

I got that a lot; my elder brothers were six and seven years older; occasionally relatives lost track of me. I was happy enough to pour him a cup of tea, the better to get my hands on a one of the old dear’s prized buns; after baking she typically hid them to prevent their rapid disappearance.

He took a sip of tea from his mug; kept smiling with a slightly vacant, almost wondrous glint in his eyes. My mother excused herself, explaining that she was in the throes of cooking the teatime meal, though she didn’t automatically invite him to stay for it. That would have been the usual protocol; insisting over the mild protests of guests that of course they’ll stay for a meal; we wouldn’t hear of you stepping out the door on an empty stomach. We were anticipating my father’s arrival for tea – our supper; dinner was the midday meal.

I heard him pulling the black Ford Cortina in the front gates and was waiting in the hall when he turned the key in the front door, eagerly on hand to give him the good news, “Dad, your brother is here!”

Far from the joy I was expecting, his jaw dropped as the news registered. Failing to acknowledge or greet me, he brushed by without removing coat or hat, almost dived in the living room door.

Left behind in the hall, suddenly without warning I could hear him erupt on the brother, shouting and roaring at the top of his lungs. I poked myself just inside the door as my father continued unloading, upbraiding him from a height, what the hell was he doing here, how dare he, get out this minute, called him a right blackguard showing up in that state – an uninterruptable diatribe that went on for several minutes.

“Sure, I only stopped by to see you,” the taken aback brother said defensively. My father had completely lost the plot. I froze in shock, wanted to head for the hills.

My sister remembers hiding in another room scared by the roar of unrestrained anger. Our household followed the Irish norm, emotions were kept bottled up tight, corked. Like the seafarers of the Aran islands, their curraghs bobbing on a rolling sea, we lived with the awareness, unspoken, that a storm induced wave could any minute sweep us away without warning.

But a deadly wave was a rare phenomenon, feared yet far from the normal run of things. My father’s emotion was a storm unleashed, out in the open, triggered we’d call it today, and landing not only to sting him and his brother but collaterally to unnerve my mother, sister and I. M

y upset father marched out of the living room, disappeared up the stairs, his part in the drama for now complete, to stew in his own upset. Mother was left to pick up the pieces. She had to drop everything – never mind the meal. She surely felt rattled, perhaps herself annoyed at having to mop up after him, because she asked me to accompany her as she loaded my uncle into her brown Austin A40. I sat in the back.

We never did this, drop our daily routine to drive into town in the darkness of the early evening. She drove down Palmerston Road, then over the canal and into town via Camden and Georges Streets, around by College Green and Westmoreland Street where animated neon advertising lit up the city, to turn left down the quays near McBirney’s department store where he could get a bus back to Kildare.

There was quiet in the car but tension had abated. She was concerned for him. “Are you all right,” she asked him as he alighted, “do you have enough for a sandwich and the bus?” He thanked her and got out to walk across to a parked bus. I hopped into the front seat wondering if that was the right bus, who would meet him at the other end.

We drove home wordlessly through the Dublin rush-hour, ate our teatime meal in silence, my father quiet, not a word out of anyone. The visit, the anger, nothing was alluded to. He turned to the newspaper. A calm had redescended. Later that night I came upon her practically whispering into the phone, ringing a relative to make sure he had made it home in one piece.

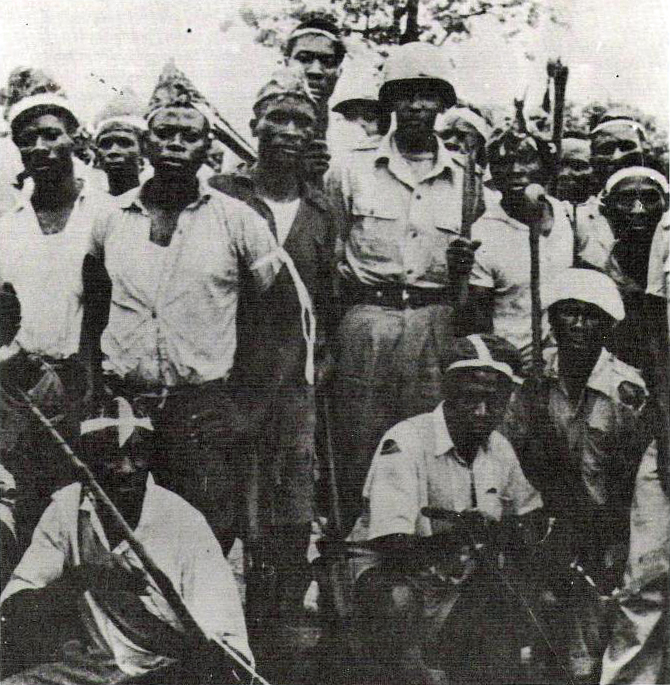

Baluba militiamen in 1962.

The Niemba Ambush

Having seen the soldiers off to the Congo my father made it his business to take me up to Phibsboro in November 1960 for the second massive gathering in Dublin in a single year. Once again, we joined thousands, this time crammed along a funeral route to Glasnevin cemetery. Nine Irish soldiers from the Congo were to be buried, the first to be killed in combat in the modern era. The Niemba ambush.

I thought that nobody was supposed to really attack or shoot at soldiers with blue helmets- not guns nor poisoned arrows nor anything of the kind. Yet, eight of them had been wiped out in Katanga in a Baluba-led ambush, smitten by arrows we were told, in what was thought to be a case of mistaken identity, the assailants having possibly mistaken Irish U.N. troops for European mercenaries.

A survivor wandered in the wrong direction only to be caught and killed later. The funeral after a solemn high mass led by the archbishop was massive. I’m not sure how I got chosen to accompany my father; my elder brothers tells me he would have made his own way there on the bus.

My father and I set out in the Ford Cortina. I watched him closely as he as he worked the wheel-mounted gearshift. Crossing the Liffey near the Four Courts, he parked on a residential street before we walked to join legions of others gathering from all directions near Dalymount Park.

The closer we go to Glasnevin the thicker the crowds got, thicker even than at the send-off parade only much quieter. When we could get no further, he huffed and puffed, tried to lift me up to see. Soldiers with blue UN shoulder patches and guards saluting solemnly lined the route in front of the crowds.

Eventually, slowly, quietly, as the cortege drew nearer, all the men took their hats and caps off. A green jeep appeared pulling a gun carriage for the officer, with an honor guard astride at walking pace.

The slowness of it, respectful, solemn, gave me a sad feeling, like a pang of hunger in my belly. Someone whispered the officer’s name, Gleeson. God be good to them, a woman intoned. Four huge open top lorries followed at that same slow pace and flanked also by the uniformed comrades of the dead.

Four lorries with two coffins each for the ordinary soldiers. Nobody remarked on the different treatment for the officer and enlisted men. The coffins had Irish flags, with flowers and soldier caps on top, along with blue UN insignia.

They were crawling toward Glasnevin cemetery and there was no talking or bantering going on this time– just silence in the crowd, everyone blessing themselves, straining to get a look at the coffins, then staring at the ground, a few people working rosary beads, reciting away in murmurs.

The cortege passed in slow motion; slow marching soldiers’ accompanying the lorries to the sounds of their own boots and the low hum of engines. I got a really good look at the gun carriage. Gleeson.

The mournful funeral procession gliding by, honored by the presence of thousands standing in respectful silence, made sense in my young boy’s world, a blend of reality and fantasy – national solidarity expressed in Catholic prayers.

Glasnevin Cemetery.

“You couldn’t get near Glasnevin with the crowds and dignitaries,” Dad told my mother later.

“Daniel O’Connell, the Liberator, is buried up there,” he told me, “the soldiers will be up there with him.” I used to get mixed up between the multiple patriots across the seven centuries we were under the thumb of the English, except for the executed leaders of the 1916 Rising at the GPO – Pearse, Connolly, Joseph Mary Plunkett, Tom Clarke and all. They issued a proclamation to Irishmen and Irishwomen – lots of people had it framed on their walls but I never read the whole thing. “Imagine shooting a sickly poet or a wounded Labour man; that’s what the English did after the Rising. The gobshites,” I heard people say, even fifty years on.

The crowd thinned away slowly after the last of the procession passed but my father lingered, knowing the funeral was still going on up the street at the cemetery where the Taoiseach, Lemass, and government ministers awaited hats in hand. Finally, we started the long trek to where he had parked the car, near the North Circular Road. He threw his shoulders back and walked quickly. I had to take big steps, nearly run, to keep up.

When we got home, my mother doled out scalding hot tea, a rasher, egg and fried bread in the dining room. “God rest them and keep them, the poor divils,” she said. Later, the old man would read the paper and smoke a Carroll’s Number One at the table when she cleared off his plate. I would have scampered out the back garden to kick a plastic ball with my black brogues or maybe donned the plastic blue helmet and marched in the twilight along the path to the bottom of the garden, keeping a sharp eye out for Balubas or Belgians.

We hadn’t talked in the car on the way home – there was nothing to say. As the light faded in the garden, I was wondering if the soldiers would still be up there in Glasnevin now that everyone had left; were they glad to be home in Ireland; would they be lonely, miss being at home for their tea; were they in heaven or Glasnevin or where were they?

We depend on readers’ support. You can contribute on an ongoing basis via Patreon or through a one-off contribution via Buy Me a Coffee. Any small amount is hugely appreciated.