Mere colour, unspoiled by meaning, and unallied with definite form, can speak to the soul in a thousand different ways.

Oscar Wilde

One of the most dramatic dives I have ever completed was the awesome Fastnet lighthouse off the west Cork coastline. As a young diver of barely sixteen I was on a dive trip with forty other to explore that stretch of coastline.

Blessed by one of those rare days when the might of the Atlantic Ocean is transformed to a glass like surface we braved the journey out to this rock known as ‘Ireland’s tear drop’ to Irish emigrants: it being the last view of their homeland before the dangerous journeys to a new life in the Americas began.

Fastnet Lighthouse, 2005 By Tom from Aberystwyth, Wales. Wikicommons (cc)

Fastnet lighthouse is located thirteen kilometres off the Cork coastline and is an incredible feat of human ingenuity. Built to withstand the mighty swells that normally pound this part of the coastline it towers forty-five metres above the Atlantic Ocean.

First constructed in 1853 after a shipping disaster involving the loss of ninety-two lives, it was rebuilt by the Irish Lights in 1897 in its current form, using 4,300 tons of dovetailed Cornish granite.

This was the dramatic backdrop to a dive that even a quarter of a century on stands out in my memory as something truly special. To my naive young self it seemed that dives like this were the norm, as opposed to an event of great note. I have yet to return to this site, with mighty Atlantic swells forcing me back more than once.

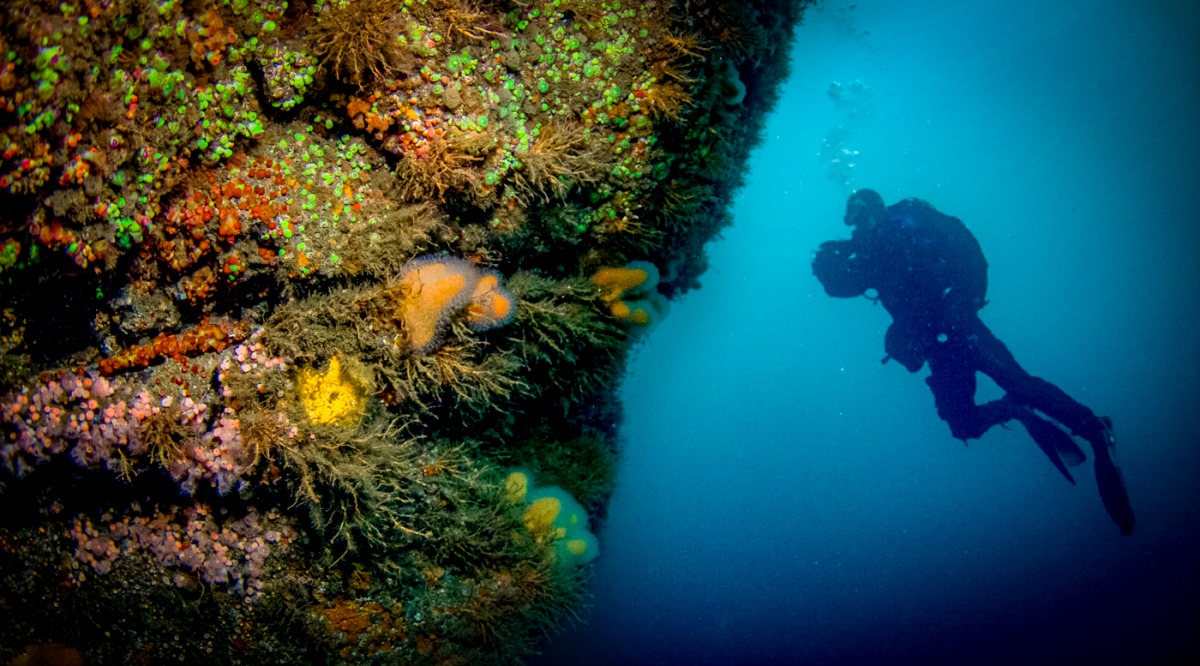

I surfaced from the dive blown away by the walls that dropped from the surface heights down to depths of eighty meters, with a shipwreck also noticeable in the depths below. The sheer cliff faces was dressed in colours reminiscent of the Bermuda shorts I had worn as a youngster in the 1980s.

Neon colours of pink, yellow and green dressed the sheer faces that in the crystal clear waters of the Atlantic lent me an unmistakable feeling of flying.

A French photographer that was diving in the group with us surfaced raving about the colours of the Jewel anemones colonies. I was instantly intrigued at how such colourful creatures could survive and thrive in such a remote and windswept location.

At that point I had only taken a few underwater images, mainly with disposable cameras, so the French photographer’s excitement in response to these colourful creatures left an unmistakable imprint on my younger self. As my underwater photography career expanded, the subject I have always sought out has been this beautiful and colourful creature clinging to the most exposed rocks in the most remote locations.

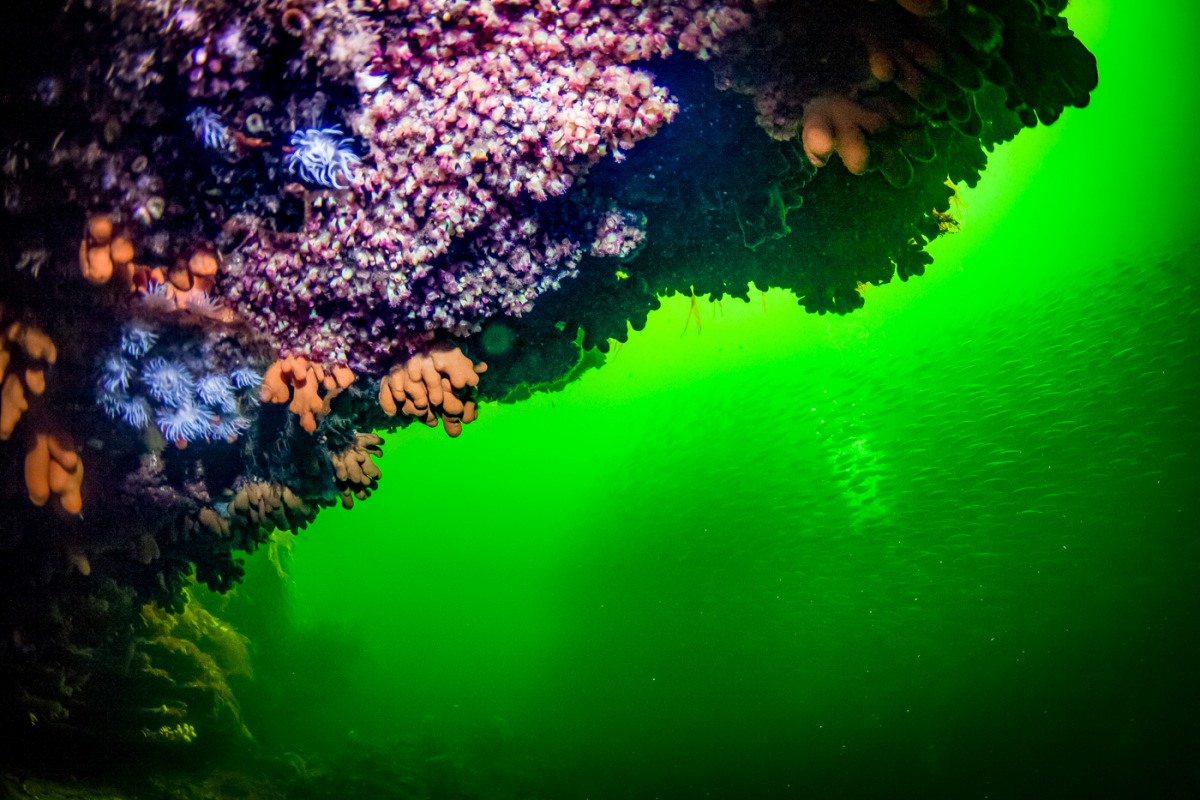

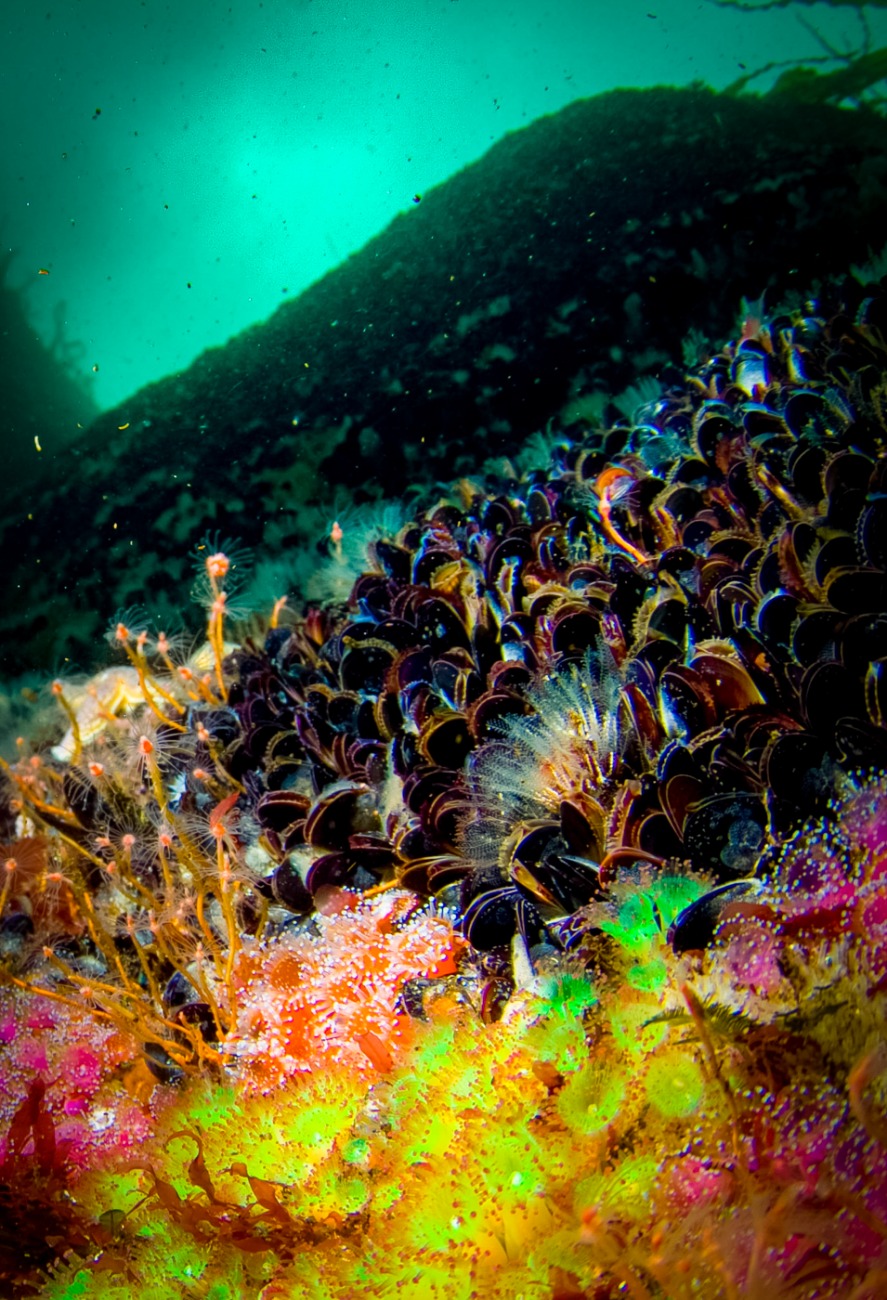

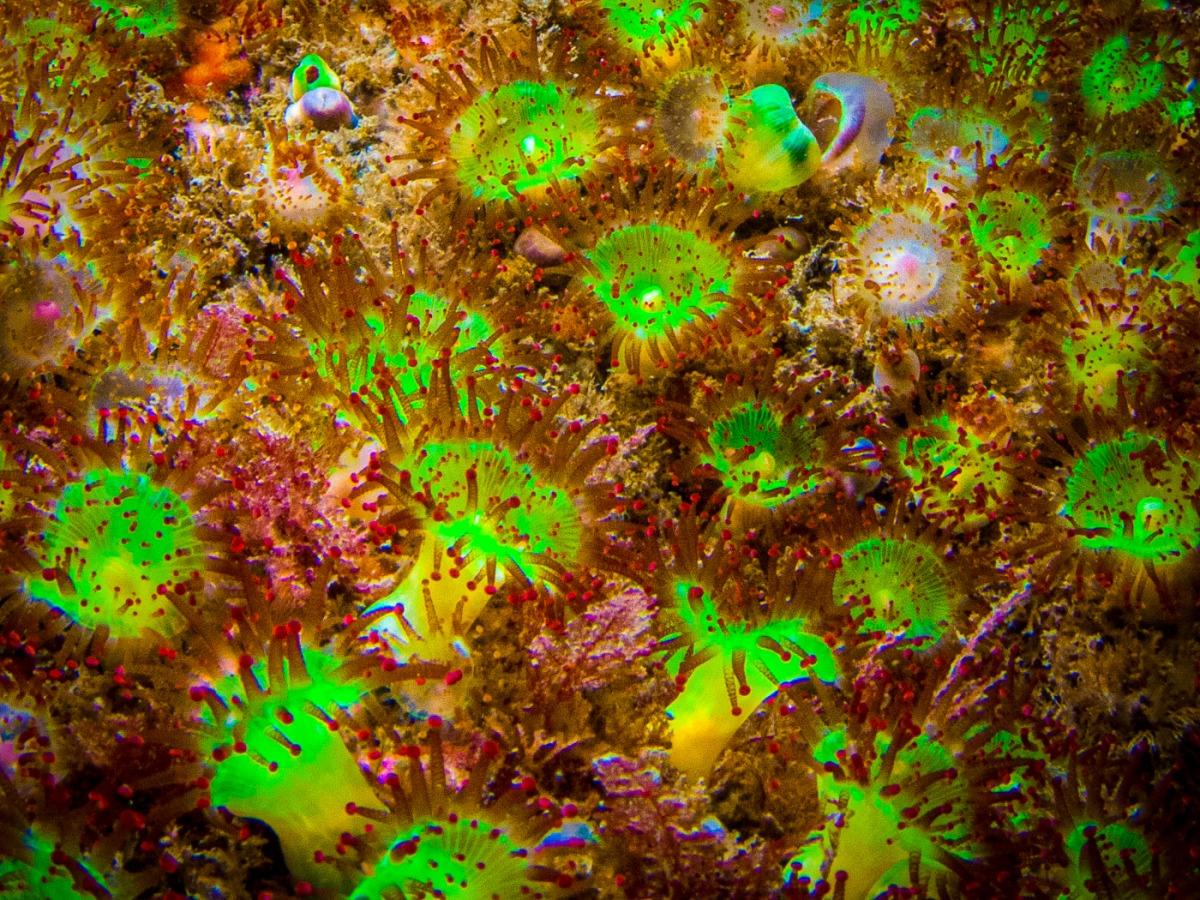

Jewel anemones are asexual, reproducing by splitting into two identical species connected by a thin sliver. They form colonies of identical creatures on rock faces up to eighty meters in depth. They thrive in high energy zones, where the waters of the Atlantic wash over them with great force.

Their method of reproduction means you normally find patches of colour fighting for real estate. Neon Green battles with neon pink for prime locations on the surface of underwater cliff faces. Rarely seen on the east coast, they are to be found in all of the most dramatic sites I have dived along the Atlantic coast.

As well as finding them on cliffs they can be found clinging in a similar manner to shipwrecks, fighting the same battles of colour for the best seats on the exposed sides of sunken vessels.

Over my time diving whenever I have had the chance to dive with a camera in hand I have sought out battles of different colours, and tried to capture the beauty that the colour imparts on the final image.

In showing the image to non-divers I relish their disbelief that such colours exist below the waters that surround this country. It is assumed that only in the tropical zones where coral reefs bloom can such vibrant colours exist. This notion is shattered by the beautiful vibrant colours of these incredible rock clinging creatures.

When training new divers the images of jewel anomies always brings an audible intake of breath as they realise what to expect on future dives. Dive sites around Ireland are actually filled with colour, but the nature of water and the way it absorbs light means that in order to bring these colours out in their true glory the underwater photographer requires powerful strobes, or flashes, to reveal the vibrant colour.

As a diver setting out, one of the first pieces of equipment to acquire is a torch. In recent times the technology driving the underwater torch has gone through a massive innovation cycle with the introduction of LED torches.

Now for relatively little money a powerful torch can be purchased that only a few years ago would have required a suitcase battery to power it.

Some of the best underwater photographers in the world describe the technique of capturing underwater imagery as painting with light. The placement of the light or strobes will completely change the final imagery with the true colours being brought out through the introduction of artificial light, which was absorbed by the water column on to the subject.

The colour patterns that these amazing colonies produce across the walls, spread out around the Irish coastline, are truly dramatic and the battles between the different colonies make for the most amazing and dazzling splashes of colour, unique to the geographical location of the dive.

The translucent nature of the species means they can bring incredible colour to either macro or wide-angle photography, like imagery of flowers above water. The colours bring a light into even the darkest of moods.

Another dive season has ended along the Irish coastline in recent weeks, and thankfully it has coincided with the return of travel restrictions, so although 2020 was a much shorter dive season I had the opportunity to get some exciting dive trips in during a truncated season.

As the Atlantic storm cycles move quickly through the alphabet of names the waters are churned, with visibility dropping to only a few feet, and so the number of divers entering the water drops dramatically. Although there are many dive sites dive open throughout the year the restrictions on travel means divers are unable to travel to these sheltered locations. As the seasons in our marine environment moves into the winter stage only the bravest of divers head into the seas to get their fix of the underwater world.