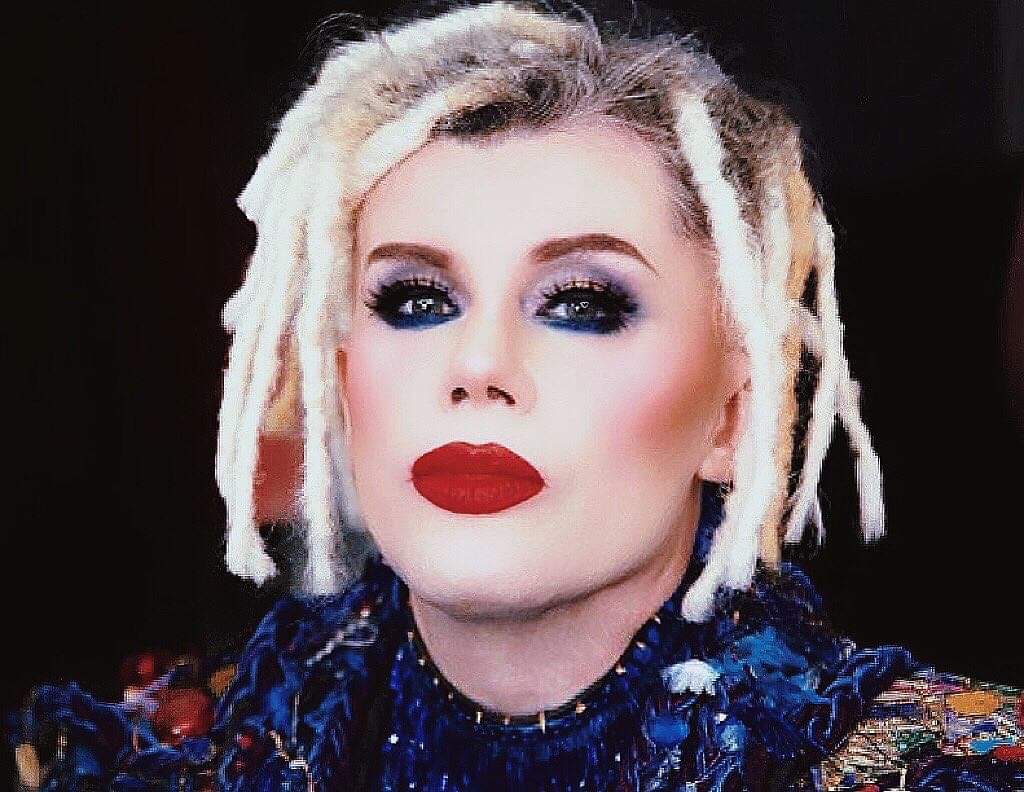

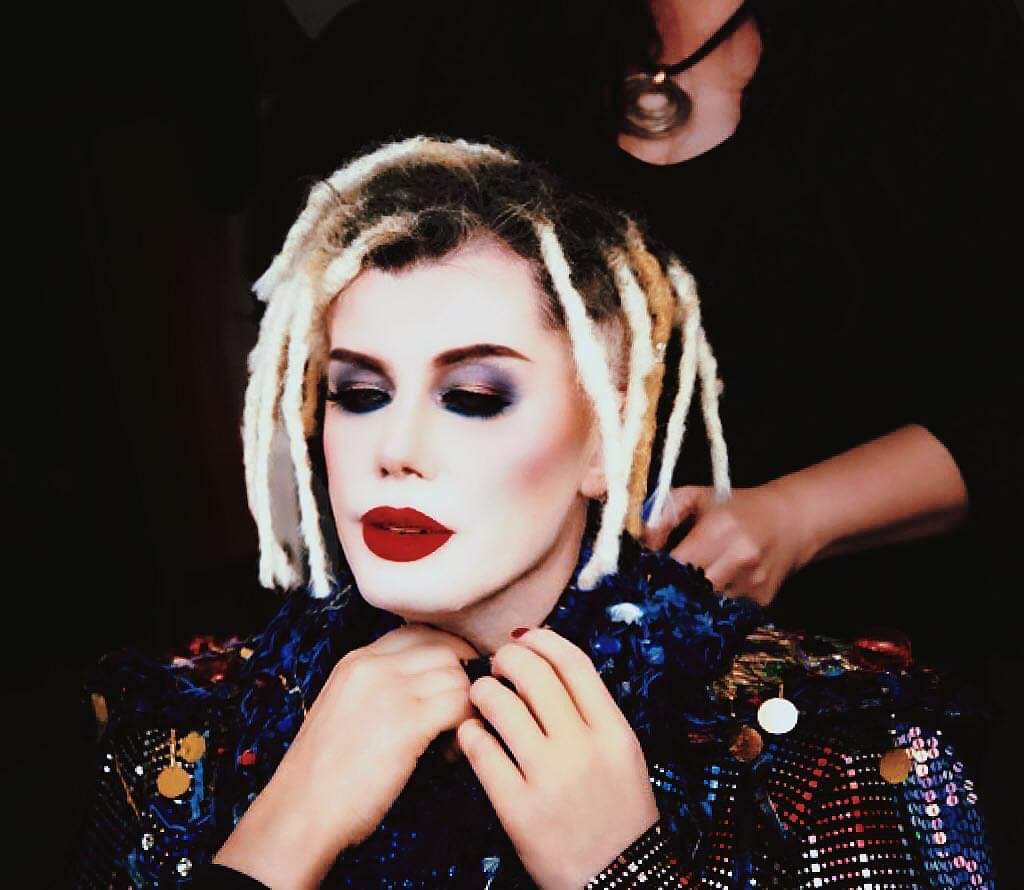

Paul Francis Quin has proven himself an approachable enigma. The myriad glamour shots gracing the cover of his upcoming album ‘Life on Earth’ and various assorted publicity materials tend to portray him as otherworldly, a strange mixture of glamorous and uncanny. Nonetheless, he is quite happy to talk, in his wryly calm and personable manner, about any subject, no matter how taboo. In fact, taboo subjects are his speciality. They are fuel to his creative engine, and vital to his artistic expression.

“It’s been an interesting journey, especially at this point in history,” he tells me over the first of several hour-long Zoom calls we have. “But I can’t deny I’m excited to see these songs released into the world at last.”

Quin is a Wicklow native, born in Bray in 1971, and his serene, cut-glass accent is still inflected with the earthy intonations of that venerable seaside haven. The electro-pop singer-songwriter and exeperimentalist composer is on a homecoming journey of sorts. At the time of writing [note: this date has passed], his long-awaited solo album ‘Life on Earth’ will see its launch at Dublin’s Peppercannister Church with a gloriously disparate personelle, after a heady 2.5 years (“a slight exaggeration,” Paul purrs coyly) in the making. This represents a definitive return to music following an extended hiatus, although, it must be stressed, not a complete departure from it.

The designated venue is an interesting one, not least for its former ecclesiastical status. Paul tells me, a few months following the Zoom call and in person this time around, that: “To be quite honest, I was gagging to get on stage in somewhere like the Grand Social or the Sugar Club whatever, and do some live work there. Generally, I don’t sing live very much, I much prefer to work in a studio. But once I resalised I was actually still capable of it, I just pushed myself to get back to it. I’m at least determined to get back up on stage and at least do an album launch, and do a proper show with creative design and costumes and all that. It’s a dream away at the moment, but dreams are how I run.”

I jokingly suggest he do an alfresco gig, charging people a fiver per head; he politely laughs such a notion off.

“I mean, I am also just asking myself where did all the time go, really,” he says, laughing. “I didn’t do much music-wise, really. I mean, I had a nine-to-five job and then I went back to college, and all this time has flowed by. I remember how prohibitively expensive hiring out a recording studio could be back in the 80s and 90s, and I remember thinking I could never re-enter one again. Then again, I remember my Dad, who had a really philosophical take on life, saying to me. ‘You are going to be a very late starter. But you are going to get there’. Not sure where he meant. But I got SOMEWHERE, I suppose!”

Image (c) Billy Cahill.

EgoBoo Studios

Thankfully, such a dismal outcome has ultimately not materialised for him. We are both in the control room of the subterranean confines of EgoBoo Studios on Fitzwilliam Street, having just been buzzed in. Next to me sits Greg Malocks, EgoBoo’s owner and chief sound engineer (and now, musical director of the entire enterprise) working through a series of levels with an air of close absorption. The ensuing conversation is punctuated by occasional clicks coming from the recorder console as he works his digital magic. This is no problem of course, Paul is happy to defer to his expertise. “I need to come into a place like this,” he admits. “In order to work with a more structured environment. Even if I had a home set-up, I don’t think I’d have enough gauge of quality control and I’d never get anything finished as a result. I need to be in an environment like this.”

Paul himself lounges opposite on the studio couch, a punkish vision in a longsleeve shirt, docs and sleek denim, with long, serpentine Medusa-esque, peroxide dreadlocks and makeup stylishly pale enough to make David Bowie (were he still with us) envious. He is far from blase about the studio set-up, however, preferring it to a more home set-up favoured by many during the last two years.

“I need to come into a place like this,” he admits. “In order to work with a more structured environment. Even if I had a home set-up, I don’t think I’d have enough gauge of quality control and I’d never get anything finished as a result. I need to be in an environment like this.”

“You need a second ear, sometimes” Greg chimes in, without taking his eyes off the flashing blues and greens on the monito before him. “When Paul’s singing, he needs to be concentrating, and with a second ear, suggestions about what else he can try come about more easily. It definitely helps.”

Paul nods. “I think when there’s someone else present, it brings something else out of you as well. There is essentially an audience there, albeit one I can bounce ideas off. The love of stacling harmonies is something me and Greg share. I’ve often worked with producers and engineers in the past who would say ‘I think you’ve enough harmonies now,’ and the fact is, I can’t get enough of them! If possible, I’ll have a full choir of hamrony behind my vocals.”

Day 7 of highlighting beautiful writing from stories you recommended to us!!

Today we're recommending, "Leah's Gaff" by @danwadewriter, published in @VoicesCassandra and recommended by @ggrace1984https://t.co/SpgZr8Ptxb

— ShortsthePodcast (@ShortsthePod) October 15, 2021

A Breath of Fresh Air

Right now, he’s listening intently to the latest mix of a new untitled song, a pure 1970s disco-tinged track which, as it transpires, is actually for an entirely different project. Despite the studio’s confined, almost windowless space, Paul describes it as ‘a breath of fresh air’, allowing him to experiment with sounds quite divergent from his usual style, which has been nebulously described as very ‘eighties-esque’ in style, tightly syncopated and synth-heavy.

“People are always saying to me, ‘your music is very ‘eighties’, and no matter what I do I can never seem to get away from that. Or maybe that’s just because of the way I sing, I don’t know. But this other friend [dreampop songwriter Keeley Moss, who will also be opening for Paul at the Peppercannister gig on the 11th]had a track that was a bit more of a disco groove to it, and I thought it’d be interesting just to try to adapt a style that also manages to retain a bit of an indie feel as well.”

I mention The ‘Weeknd’, and his similar use of synth and uptempo beats in tracks such as ‘Blinded by the Light’ and ‘Save Your Tears’; songs that manage to simultaneously sound retro and futuristic. “It’s almost like a pastiche,” Paul says, “taking that sound and refitting them for a new generation. Even just listening to the instrumental [of ‘Save Your Tears’], you can tell it’s amazing track even when denuded of vocals. I’d have different lyric and vocal ideas for it, but it is a superb piece of pop music. And pop music is often the hardest to do because it has to hit the ear almost immediately. Whereas soul and R’n’B you can let grow on you more organically, but pop must have that instant grab for people. Almost like Eurovision, in a way.”

I ask why in hell he’d stoop to comparing himself to Eurovision, to general amusement of all present company in the studio.

“One can always hope,” he smiles.

This essay, a meditation on #depression and #toxicmasculinity, was published in @VoicesCassandra

a year ago. Since #Covid, I'm certainly a lot more grateful for what I have than what I don't. https://t.co/y11yBPStaX— Daniel Wade (@danwadewriter) December 12, 2020

Behind Closed Doors

Everything happens underground now. Or at least, behind closed doors, within spaces impounded by our boundaries, with face-to-face communication kept to a minimum, as tablet, mobile and laptop screens now stand in for sociability. We are visible to each other only through screens, our voices reduced to garbled, disembodied transmissions over a Zoom audio feed. Even those of us who may live a few miles away from each other, even short distances, seem, at times, impassable.

Lockdown has been an atomising experience for virtually everybody: the blurring of the work-life balance, to the government-prescribed restrictions over not being able to leave one’s home, then one’s county, and finally with an inability to fly overseas, as well as the basic need to socialise in large groups (though this slowly but surely starting to change). The daily monotony, shot through with a vague tension of perhaps being next in line to be claimed by the pandemic, was once described in a half-joking fashoin as ‘the new normal’, a phrase many have abandoned as mounting imaptience. A sense of unreality has slipped into the very fabric of reality itself. The very autonomy we take for granted as adults has been brutally curtailed. Many of us wonder when and where we might see our friends and loved ones again. News of the impending climate collapse and a resultant creeping sense that the world is on the brink of an ill-defined but very imminent oblivion aren’t helping.

A lot of this is doomsday thinking as well: the temptation to fall into it is on the increase.

At the time of writing, the most recent restrictions have been tentatively lifted – though right now, it feels better to be discussing something, anything, other than the pandemic, lockdown restrictions and vaccines. News of the Delta and other assorted variants make for distressing reading, even with the rollout of a multiplicity of vaccines and much of the populace having received their jab (though, the presence of anti-vaxxers and anti-maskers keeping the pandemic of life support remains an ever-present worry).

Many artists on the P.U.P. now face having thiers cutoff unless they branch out into separate industries. Impatience with extended closures mandated by the Irish government’s directive to keep all indoor music events effectively cancelled. This was estimated to last no more than a fortnight. Now, nearly eighteen months on, live music in smaller venues remains illegal, with no roadmap for the event industry in sight. For many artists and creatives, ‘first to close, last to reopen’ has become a defining mantra of the Covid era.

The results of this are manifold. It seems we are at the risk of losing much of what made the nightlife so exhilarating. The unique intoxication that rises not just from a few pints and a spliff but from the very of sociability and togetherness itself, of being in the company of one’s peers and engaging in a shared sense of communal euphoria and solace. Dublin’s streets on a weekend evening are as likely to be deserted as they usually are in the midweek. The possibility that many of us are beginning to forget that unique euphoric rush of fellowship brought on by is now a horribly real one.

Of course, it is slight exaggerration, at least in the Anglophone sphere, to call this the apocalypse in easy mode, and there are far more urgent problems at hand than the halting of live performance and msic events. There is also an idea circulating that, post-Covid, there will be a flowering of creativity comparable to that of the Renaissance, which itself came gradually about in the wake of the bubonic plague. A generalised reaffirmation of life may come about from so much isolation, so much togetheness relinquished.

Frank Armstrong reviews a new book on the Irish government's response Covid-19 and wonders whether it will be said once again: “We didn’t know, no one told us”https://t.co/vikPQsuFMa @broadsheet_ie @danieleidiniph1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) May 25, 2022

Suspended Animation

It could be argued that lockdown is comparable to being in suspended animation. For many people, not just creatives, this has been a strange period of working from home and thereby taking it upon themselves to make a project happen. Dispiriting as the last year and a half has been, many creatives have demonstrated their endurance and the commitment to their art. Moreover, the technological advances of 2021 have permitted many artists to create and work unimpeded by limitations as studio time and costs. Nonetheless, this isn’t ideal either.

Yet, we are alive. We have survived a pandemic and all its accompanying madness. I consider myself healthily cynical about most things, but I doubt I am naive for being thankful to be alive, with my loved ones still here and my work still invigorating me.

It’s an overcast afternoon in early July of 2021. Gunmetal clouds lurk sluggishly overhead, the air heavy with the threat of rainfall. Overcast days in the city centre are nothing new or unusual, but for the last year they’d taken on a grimly hazardous feel. Even in summer, flurries of chill air can come blasting out of nowhere, as if to remind the average pedestrian of the universe’s innate precarity even at street level. The vague sense that perhaps one should not be out in broad daylight for too long was constantly hovering at the base of my skull.

Being out of the city centre for large swathes of time had also rendered it slightly unfamiliar. The buildings that hovered above me seemed alien. I felt like I was passing through a town I’d no previous knowledge of, having to stop every few minutes to check my Google maps and see if I still had the right place – even though a year ago I could traverse multiple streets and backlanes without having to even look up sometimes. The ongoing operatic thrum of traffic and buskers, bike couriers and people generally getting on with their lives had all but ceased, save for a few meagre pockets of people also going about their business.

Working to a Deadline

After eighteen months, the album is more or less finished, though with some quite-necessary mixing still underway. Working to a deadline can be as good a motivator as any, and the focus has thus far been sustained toward that goal. As any muso worth their salt will tell you, a spirit of collaboration is key to ensuring any album is the best it can hope to be, and ‘Life on Earth’ is no different, boasting a sizable personnel on a very disparate plethora of instruments.

And Paul, for one, welcomes the opportunity to be able to work in-studio again. His determination to see the album completed is heartening – as is his (ithin reason) refusal to be deterred by the pandemic and its attendant restrictions. I ask him what, if at all, effect the pandemic had on the albm’s production.

“I think lockdown actually helped!” he laughs. “It allowed me to focus on one thing (i.e. writing and making a record) without any other distractions like pubs, parties and the need for new clothes, new hair, new shoes. When all the background noise was taken away, it allowed me to hear the music in my head. At the same time you know they say the whole world was in suspended animation and that created it’s own little creative zeitgeist. You plugged in or you dropped out completely!”

Despite the relative freedom offered by advances in recording technology, enabling most people to theoretically record, mix and finaise entire albums from the safety of their living rooms, this is no guarantee of a high quality finished product or even of quality control: “I need to come into a place like this in order to work,” he says, “because, otherwise, I wouldn’t structure it well enough, because even if if I was recording at home with all of my equipment set up, I still wouldn’t possess enough gauge on quality control, and therefore would never get anything finished.”

“Much of the songs are more synth-pop, with some orchestral elements mixed in as well,” Paul tells me. The latter elements, he asserts, is largely the influence of the aforementioned and ever-prolific Aidan Casserly, the maestro behind such recent albums as ‘Incubus’ and ‘Ballads of Sorrow’. Aidan’s hand in co-writing “Be Yourself Girl” has proven vital to ‘Life on ‘Earth’s longevity.

“I never got to do a full album with Aidan,” Paul clarifies. “Prior to that, we’d done little demos here and there, though I’d alway wanted to do something a little more substantial. This album really started with that song ‘Be Yourself Girl’, which Aidan added both the keyboard and sax to. From there, he hept sending me bits and pieces until eventually it began to take shape.”

At the time of writing, Paul is currently in the promo phase of putting the album forth, doing the usual round of interviews and trying to see it gain airplay across as many platforms as possible. A Herculean task, some would argue, but also doubly complicated in that he has been trying to do so in the midst of a global pandemic as well. He is certainly far from alone in this.

In that time, he’s also managed to amass a formidable crew of collaborators and other musicians to join him onstage when the big night finally rolls around. If the measure of a man lies in how his peers speak of him, there is no shortage of hossannas being directed Paul’s way by his tribe. The aforementioned Keeley Moss is especially forthcoming in her praise of him, telling me: “Paul is a flamboyant force of melodic magic, who delivers a torch song like few others. There’s a lavish grandeur to his Art-Pop that brims with all the tasteful grace of a sonic connoisseur.”

Meanwhile, Pheonuh Callan-Layzell, bassist and co-songwriter of heavy metal outfit Beyond the Cresent Moon, and Paul’s longtime friend and designer, tells me: “There’s a lot of creative symbiosis with what we do. Paul’s very aware of what he wants and how he wants to present his work, and he tends to be really spot-on with what he’s aiming for. He’s quite magical as well. I mean, the Paul that I know and the Paul that I see, whether on stage or in a music video, say, are to very different people, which is applicable to a lot of artists, I’d say. The Paul I’d chat to and the Paul in ‘show-mode’ if you like, are almost complete inversions of one another.”

"They shoot pool like they’re born for it. Some for cash, others for pride or thrills; there’s no sole reigning champion. Anyone might wear the crown." Niall is new Fiction from @wadeinthewate11 https://t.co/2WVWURIsiw@broadsheet_ie @Andrea_Rey48 @CSBlenner @IlsaCarter1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 12, 2020

‘Sebastian and the Dream’ Fame

As a full-length album, ‘Life of Earth’ originally started production under the auspices of singer, composer, producer, electronica wunderkind and multi-instrumentalist Aidan Casserly, of ‘Sebastian and the Dream’ fame. Of Paul, Aidan tells me: “I’ve always seen Paul as a very unique individual and free spirit/thinker. I’ve only met a few people similar in my life and they always bring out great creative energy in creative people such as I. His humour is pitch perfect and generous and cutting when necessary. I think we may have met in a previous lifetime, but that’s another conversation!”

If the two have a shared thematic concern, it is with the underdog, the outsider, and anyone generally unmoored from mainstream society, in particular the many upheavals experienced by the queer community and the often-seismic changes that Irish society has undergone in the last three decades. ‘Be Yourself Girl’ addresses such themes directly, insofar as, lyrically, it depicts the struggles of a young trans-woman coming to terms with the vagaries of an increasingly mercurial world. July saw the release of ‘Be Yourself Girl’, the first single off the album, but there is little time to be euphoric. In a seperate track, ‘A Better place’ lyrical approach and the album’s cover, Paul assumes the aloofly compassionate role of a guardian angel, assuring the listener that

IF I COULD CHANGE THE WORLD

you know I’d make it a safer place, for you

As the title suggests, the song is a hymn to love at its most altruistic, and that the hope for a better world is not only possible, but also quite plausible. Despite his often-acidic wit, Paul’s music in fact comes from a place of deep compassion and empathy for such corners of the human experince, corners, that, despite the progress of even the last ten years, still remain sidelined. That sense of being sidelined is something Paul himself knows very well.

If electro-pop could be deemed culturally subterranean in the contemporary Irish music scene, this is not to say it is not rich in its variety of acts. If it is treated at best as niche genre of oddity or, at worst as a target for critical ridicule, Paul will soon prove otherwise on both counts.

Covid or not, the work can often feel neverending for most musicians, an endless round of recording, mixing, promo on both social media and regular media outlets (if you’re lucky, that is), trying to land a performance slot at any venue you care to name, as well as plugging the album before, during and after its release. Lack of media coverage, whether in Hot Press or in more mainstream publications, remains another hurdle, though, to Paul’s credit, he has embarked on an interview campaign with as many forums as he can. For his part, Paul has not shied away from this necessary evil. If anything, he has taken to it with a certain dogged gusto:

“I just wonder how many singles get released every week, but every time you’re doing, you’re trying desperately to be heard along with everything else that’s been unleashed on the airwaves. And it’s been extra hard to grow an audience and excite some interest in your work with no gigs and venues. So basically, all you’ve got is radio and, I suppose, to a lesser extent, the livestream gigs that people are doing at home, although I’m not quite prepared for that at the moment.

“This time around, putting something out there just feels in equal measure exciting and daunting. You ask yourself, in moments of doubt, is anyone going to be even vaguely interested? And then you realise, you have to make them interested, hence all this social media stuff. And it is very easy to do it that way, but then, of course, so is everyone else, and it’s a tough job. I’m in this first and foremost for the love of it, and the passion I had once before, that has been gobe for years, has been rekindled. I have been extending my pool of co-writers and collaborators, and i now have three or four different songwriters helping out.”

It must be stressed that none of this is any mean feat. The last few months have seen the restrictions of Covid finally lifted nationwide and a hesitant return to normalcy after two years of lockdown, quarantine measures, and the months of seemingly interminable isolation and uncertainty that accompanied them.

Paul manages to remain philosophical about the entire ordeal. “Covid seems to have brought people into communicating in a slightly different way,” he muses. “I’ve noticed people have been more open to collaborating than they might have been before. Some benefit has come out it, I’d say.”

It is these same changes in communication and understanding on a wider social level in the years preceding the pandemic that similarly have influenced Paul’s return to music.

While advances in music technology and methods have made the recording process comparatively easier when working in isolation, the roadblocks set in place by our inability to work together face-to-face has lessened such opportunities. This is before we even mention inflation, the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and resultant food shortages that have occurred. To be able to see such a bleak period in human history through and to emerge with a fully-fledged work of art on one’s hands is testament to both one’s resilience, the indomitable will to endure, and perhaps even live again once the dust has settled.

Daniel Wade reviews Peter O'Neill's poetry collection Henry Street Arcade addresses the character of the flaneur to the backdrop of Dublin’s streets and architectural mismatches.https://t.co/vUj36HhdZa@broadsheet_ie @wadeinthewate11 @Andrea_Rey48 @Elzobub #flaneur

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 3, 2021

No Stranger to Tests of Character

Yet Paul is no stranger to such haphazardly-inflicted tests of character. His personal history, a crucial spur to the overall composition and recording of ‘Life on Earth’, is riddled with such tests. Paul is a proud member of Dublin’s gay community and has been so from a very young age; the album serves as something of a songbook for the gay experience as Paul knows it, contemplating the length and breadth of social change that has occured within Irish society over the last two decades.

After singing at family gatherings and being encouraged to sing his local choir upon his discovery that he had effortlessly perfect pitch, Paul turned his musical attentions to guitar and piano before eventually joining up with John Butler, with whom he formed the electronic synthpop duo BiaZarre. Their first single ‘A Better Place/The Colour of Rain’, recorded in Windmill Lane, was released as a double A-side in 1989. “It did well on the Irish airwaves for most that year,” Paul recalls. “Or, at least, it was on the radio every day for at least a month. We played gigs in Sides DC, Blondes on Leeson Street. We were very influenced by synthpop, all that New Romantic styliings, which, little we realise at the time, was starting to go out of fashion.”

As it turns out, the first of that single, ‘A Better Place’ is making something of a comeback along with its maker: it has received a full reimagining and recording on ‘Life on Earth’. There is a poignancy to this development, however; John Butler’s untimely death in 1998 is what the song pays ultimate tribute to.

Much more than just a collection of songs, the album stands as a social document,

Artifice has long been a part of Paul’s aesthetic and personal philosophy. While mostly an aesthetic choice, it was also in part a consciously-developed survival and defense mechanism The album, therefore, is coming thirty-plus years after he left music behind and when attitudes toward LGBTQ+ people began to undergo quite the seismic sea change, from decriminalisation to eventual acceptance in the form of the 2015 Marriage Equality Referendum, which saw same-sex marriage fully legalised within the Republic. In an op-ed for Northern Irish political weblog Slugger O’ Toole, written several days after that historical day, Paul writes:

Those I had held in check for at least a couple of decades came freely and easily. Without any sobbing. They were simply tears of relief. And joy. It was now safe to cry. What had once seemed impossible was finally and unarguably here. Yet taking it all in was practically impossible… After a dirty tricks campaign against equality that must surely have reminded every LGBT person in the land of both the latent, and the blatant, homophobia that had followed several audible paces behind them through their lives, honesty and decency had won. The people of Ireland had seen through the thick smog of lies, distractions and fear mongering to the dawn of a new day.

This is not to say equality for queer people has been fully achieved: at the time of writing, the homophobic double-murder of Aidan Moffitt and Michael Snee in Sligo in mid-April still confounds the nation. Such an act of brutality serves as an unfortunately harsh reminder that small, if insidious, pockets of ignorance continue to blight Ireland’s supposedly enlightened socio-cultural landscape. Renewed calls for a comprehensive Hate Crime legislation have been made by organisations such as LGBT Ireland in the wake of the murders.

Fittingly on #Bloomsday Russian-born writer based in Ireland Polina Cosgrave describes Kevin Higgins as the Daniel Kahneman of poetry in her review of his new volume of poetry Ecstatic.https://t.co/Wk18upjU1k@polina_reprint @KevinHIpoet1967 @corourke91 @danieleidiniph1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) June 16, 2022

Violent Homophobia in ’80s Ireland

For Paul, the spectre of overt, violent homophobia, so prevalent and normalised in Ireland throughout the ’80s when he first came of age, seems to once again rear its head, as if in a gesture of grotesque reminding: I haven’t gone away, you know.

In the aforementioned article, Paul writes: ‘Back then, the fight for expression of identity was a huge battle that I personally had waged upon my world and theirs. The heterosexuals. The grand majority. Aged seventeen I was now illegal but I wore my queerness like a suit of armour. Making myself highly visible and inscrutable all in one smart move. And it worked for me. But only up to a point. One had to run the gauntlet of a very real series of dangers, threats and annoyances. People mumbled discreetly about the young man [Declan Flynn, who was gay-bashed to death in Fairviw Park in September of 1982] who had been beaten to death in a park just a few years before. Ireland was a place entrenched in a deep mire of homophobia and gay love truly was consigned to the shadows. Love was not fit for public consumption, if you were queer.’

This same darkness, very real and very destructive, is one he wishes to stand against with ‘Life on Earth’. Paul remembers a time when the process of coming-out was (and for many, remains), a deeply painful experience; when the homophobic stigma endured by gay men of his generation was the norm. Ireland in the late ’80s was a far cry from the world of today where the first openly gay Taoiseach was elected into office and rainbow flags adorn virtually every shop front during Pride month.

The shame of being fundamentally unloveable over a perceived sense of difference is quite a universal one, but one felt acutely by many LGBTQ+ people, past and present. Arguably, it is actively manufactured by a society still slowly unloosening itself from the socially conservative trappings of the Church.

It must be noted at the time that homosexual activity remained illegal in Ireland. Reprehensible as its existence may seem to the contemporary mind, the infamous the Offences against the Person Act, 1861 (“the 1861 Act”) and the Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1885 (“the 1885 Act”) threatened a life sentence of penal servitude and a decade-long sentence of same respectively (itself an outdated concept and judicial practise even by late twentieth-century standards) for what each referred to as acts of ‘buggery’.

By the mid-80s, according to Paul, these acts of legislation were not very effectively enforced. Speaking on the Extraordinary Souls podcast, hosted by Mark Haslam, he elaborates: “When I first started going to bars, they would have been raided by the guards and so forth. So men were not supposed to be having sex with men. The act was considered to be illegal on the statute books. That said, I don’t think the law was enacted very strongly. But… for a long time, myself and my friends were technically illegal by our very existence. At least, what we were doing and the gatherings we had were, technically speaking, illegal, because of our desire for one another. It’s simply another version of the many ways society moulds and shapes sexuality.”

Conversely, he also was never a stranger to that subterranean world that arose in covertly defiant response to the aforementioned laws: a world where queer people could mix and mingle freely, without fear. Moving through Dublin in the mid-80s, a city and era both markedly different to now in terms of attitudes to queer people, he discovered it was also home to a vibrant-if-underground gay scene, with queer-friendly nightspots such as Flickers, Sides DC and the George [the former two now long since gone]. Paul described such a scene as: “A tiny little world of lingering stares of furtive glances. Apparently, I was home. I had no idea what to make of my new home, but there I was, regardless.”

Sebastian Reynolds regards the facility to preserve sound over decades a truly magical phenomena. His Athletics EP draws on heartbreaking loss, running and more.https://t.co/0ulYCHkvHc@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @BenPantrey @danieleidiniph1 @PindropMusic

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) June 14, 2022

Velvet Rage

In his fascinating 2005 book The Velvet Rage: Overcoming the Pain of Growing Up Gay in a Straight Man’s World, clinical psychologist Alan Downs, himself an openly gay man, writes: “One cannot be around gay men without noticing that we are a wonderful and wounded lot. Beneath our complex layers lies a deeper secret that covertly corrodes our lives. The seeds of this secret were not planted by us, but by a world that didn’t understand us, wanted to change us, and at times, was fiercely hostile to us.”

Paul knows this hostility, which, as Downs points out, was and remains systemically enshrined across much of the western world. As with many an artist before him, whether gay or straight, Paul’s own wounds feed into his work. Shame and pride go hand in hand for him, but it is not simply limited to his own experience. His track “Everything I Loved I Lost (That Day)” is a paean to his his long-dead father who, Paul movingly avers, did everything he could to ensure his children grew up knowing they were loved.

“My dad was consigned to a 1940s industrial school in Glasnevin,” he tells me, “and only after he died did we discover the extent of his physical and psychological and other trials, simply because he was a poor child with no parents or guardians. Instead of turning his heart to stone, my father channeled all his terror and rage into ferociously loving and protecting his family. His heart turned to gold. Having lost both of his parents by the age of seven or eight his greatest fear was not being there for his children. And he always was. He stayed young both inside and outside and died swiftly without any fanfare and with tremendous dignity. I think he knew very well what it was to suffer adversity from all sides, but to keep going in the hope of a better day.”

This same desire to keep hope ever-enkindled and passed on to any and all who need it is one of the chief driving forces behind the album; at the same time, the wounds it seeks to remedy are rarely ever so easily healed. I am reminded of a line in a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem, No Worst, There Is None, that I think applies to this question:

O the mind has mountains, mountains of fall:

Frightful, sheer, no man fathomed:

May hold them cheap who never hung there.

Essentially, it’s very easy to be cavalier, dismissive or even outright contemptuous of someone’s perceived vulnerability (“may hold them cheap”), especially if one has never undergone or been made aware of the other person’s struggle. Whether grief or worry or depression or extreme anxiety (“mind has mountains”), an inevitable toll is taken upon one’s emotional state, in turn affecting how they interact with the world.

Returning to Downs, he clarifies his point by saying: “Velvet rage is the deep and abiding anger that results from growing up in an environment when I learn that who I am as a gay person is unacceptable, perhaps even unlovable. This anger pushes me at times to overcompensate and try to earn love and acceptance by being more, better, beautiful, more sexy – in short, to become something I believe will make me more acceptable and loved.”

With ‘Life on Earth’, however, Paul will see the wounds caused and exaserbated by such rage finally overcome. My only hope is that it is the beginning of something better.

We depend on readers’ support. You can contribute on an ongoing basis through Patreon or on a one-off basis via Buy Me a Coffee.

Feature Image Image: Billy Cahill