We can only imagine how poetry entered human consciousness. I intuit that its emergence was linked to the first use of fire, that most seminal of technologies, whose devouring mysteries transfix us with a spirit that endows our own.

I see one among a band awakening from a dream, and entering a trance. She incants a tale of the fire’s origin, her words embodied in physical expression, which inspires the band to adapt the tools to summon the first, intentional spark.

In the flickering light that ensues the poet appears to shift shape. She is a streak of light morphing into the appearance of other animals of the forest. Her words are not common speech, but arrive in measured cadences, uncannily familiar to a mesmerised audience.

The tale she recounts, though fantastical, resonates with commonplace experiences and includes practical insights. As the narrative arcs to a point of heightened tension the poet breaks the spell with a joke, seizing the assembly with laughter, but a few remain silent.

Transfixed by the incendiary words, the band begins to chant; eventually a chorus chimes, integrating non-verbal melodies. Next a rhythm is struck, then a communal dance previously employed to intimidate a long extinct primeval beast, still lurking in our nightmares.

For a moment the forest itself is convulsed by these energies. Afterwards, or even coinciding with this, a visual representation of the performance is crafted. It is kept as a sacred object for subsequent rites.

Out of this poetic source I see four springs generating story, song, dance, and visual art. These intertwine and will eventually merge into an oceanic consciousness. The continuity between words, music and dance is apparent, while the symbol is not only the origin of painting and sculpture, but also of the word, ‘made flesh’, in script, which over time migrates from pictographic representation to alphabets, rejoining and completing its journey along the great river of poetry.

The spoken word is an animating spirit and crucial catalyst joining language to a musical faculty. The written word records and even amplifies this. Only later does abstract, disembodied reasoning in the form of philosophy arrive.

Musical Language

According to Walter Ong: ‘More than any other single invention, writing has transformed human consciousness’. The Greeks were not the first to develop it, but improved on earlier models by representing vowels for the first time, making literacy far easier to achieve.

Through this the Greeks derived great technical and intellectual benefits, but it brought the danger of abstraction, and a distancing from Nature. Socrates, a confirmed townsman, claimed he had nothing to learn from fields and trees, but only men.

In writing we encounter the dominance of the written word itself, a logo-centrism, which finds us in the narrow purview of the left hemisphere of the brain.

But according to Iain McGilchrist the origins of language lie ‘in the empathic communication medium of music and the right hemisphere, where it is deeply connected with the body.’ There is no conflict he says between this belief, and the idea language developed out of gesture: ‘Music is deeply gestural in nature: dance and the body are everywhere implied in it.’ He continues: ‘To the extent that the origins of language lie in music, they lie in a certain sort of gesture, that of dance: social non-purposive (useless).’

The origin of language, therefore, should not be seen in pure utilitarian terms.

“Useless” play in language is the stirring of poetry, but a creation that is the catalyst of Art, which acts as a form of revelation, where metaphor, according to McGilchrist, ‘links language to life’. The absence of utility in poetry is therefore superficial. It is a creative spark, bringing perception at new vantages, and sight through different lenses. Art is the resolution of the image.

Human communication is not uniquely ingenious, but we display a particular ability to measure speech in song and poetry – a mathematical sensibility in communication.

According to McGilchrist, what distinguishes our music is that ‘no other creature begins to synchronise the rhythm, or blend the pitch, of its utterances with that of its fellows, in the way that human singing does instinctively’. It would appear that we gravitate to a musical order that was established in the West by Pythagoras, who divined that a musical note produced by a string of fixed tension could be converted into its octave if the length of the string was reduced in half, and its fifth when reduced by two thirds.

Unlike ourselves, most bird species have a syrinx in their throats, allowing two notes to be sung simultaneously, as they exhale and inhale. But birdsong, however bewitching, is unmeasured. The dawn chorus is an unintentional unity, representing disconnected currents emanating from the varying concerns of often competing species; harmonious only as the voice of one Nature, spiritus mundi, or Gaia.

At its lofty height, poetry combines the order of music with profound questioning and metaphorical vision. This is a mysterious hallmark of humanity.

Grammars of Creation

Artistic beauty in its ideal, unrealisable, state is the expression of the diffuse and infinitely complex voices within Nature’s harmony. What we consider aesthetically pleasing derives from an ascetic order in music that finds an analogy in all artistic forms. The spark is poetry.

Poetry is the lute through which the voice of Nature sounds. But the instrument may be misshapen, perhaps through misuse. More tragic is when the pitch of beauty is too high for an audiences to hear.

What is poetic has a dual nature: generative and disruptive. Just as in Nature Heraclitus envisaged a fire of renewal, so poetry devours and renews. Philosophy may define beauty, including justice, at any point in time, but this is primarily exegesis rather than creation. Thus Yeats argued ‘whatever of philosophy has been made poetry is alone permanent’.

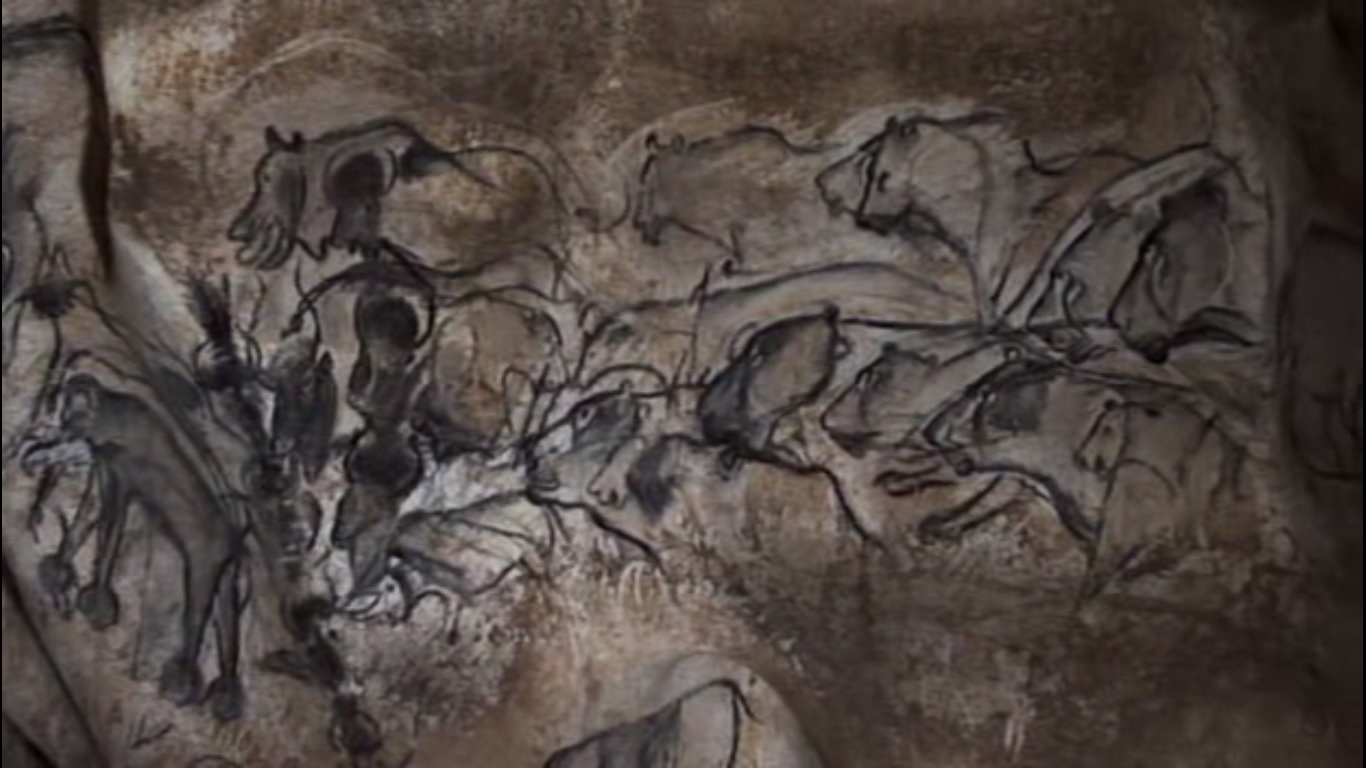

Nature demands that plants and animals of diffuse species assist one another, but we appear to be alone in imaginatively standing outside our immediate frame, situating ourselves in the lives of others through fictions, as we see first in cave paintings.

The paintings in Chauvet Cave in France were begun approximately thirty thousand years ago.

To convey such imaginings required novel linguistic constructions. George Steiner points to a grammar of creation in the use of a future tense, allowing us ‘to discuss possible events on the day after one’s funeral or in stellar space a million years hence’.

This, he says, looks to be specific to homo sapiens, as do ‘the use of subjunctive and of counter-factual modes’, which are kindred to future tenses. Steiner intuits that these emerged at the end of the Ice Age to discuss food storage. He links this to the discovery of animal breeding and agriculture.

But I see a capacity for inter-subjectivity, including a subjunctive ‘if’ clause, arriving earlier: in the symbolic language of poetry, rather than to facilitate practical exchange. To chart this grammatical genesis I turn to Rene Girard’s idea of the scapegoat, which, he argued, emerged as a means of settling differences arising out of competition acquisition of scarce resources.

‘Man is not naturally a carnivore’, Girard writes, ‘human hunting should not be thought of in terms of animal predation.’ He argues that animal domestication arose out of the use of animals in sacrifice, not as food: ‘What impelled men to hunt was the search for a reconciliatory victim’.

After mining anthropological literature he found a ‘common denominator’ of a ‘collective murder’ of a scapegoat, attributed to animals or men. To conceive of this reconciliatory victim required a subjunctive ‘if’ clause, enabling the band to channel their grievances away from self-annihilation.

When an animal victim is chosen instead of a human and ritually slaughtered the smoke rising from the sacrifice is seen to appease the gods. Thus, in the Odyssey after Odysseus returns in disguise to Ithaca, he shares a meal with his loyal servant Eumeaus who performs the necessary rites of sacrifice:

The swineherd, soul of virtue, did not forget the gods.

He began the rite by plucking tufts from the porkers’ head,

threw them into the fire and prayed to all the powers,

“Bring him home, our wise Odysseus, home at last!”

Then raising himself full-length, with an oak log

he’d left unsplit he clubbed and stunned the beast

and it gasped out its life …

The men slashed its throat, singed the carcass,

quickly quartered it all, and then the swineherd,

cutting first strips for the gods from every limb,

spread them across the thighs, wrapped in sleek fat,

and sprinkling barley over them, flung them on the fire

In Christianity this culminates in the ‘lamb of good that takes away the sins of the world.’ The language of these fictions, therefore, appears to originate in symbolic representation, which is a hallmark of poetry.

These new grammars imparted a capacity for planning, and an understanding of natural cycles, which can lead to the outlook of the suzerain: the ‘keeper or overlord’ personified by Judge Holden in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, who says: ‘Whatever in creation exists without my knowledge exists without my consent’.

But it also engenders empathy with other life forms, which recalls the Isha Upanishad: ‘Of a certainty the man who can see all creatures in himself, himself in all creatures, knows no sorrow.’

McGilchrist writes: ‘I believe that the great achievement of human kind is not to have perfected utility through banding together to form groups, but to have learnt through our faculty for inter-subjective experience, and our related ability to imitate, to transcend utility altogether.’ That is the essence of true poetry.

Poetry and Justice

Art often awakes sensitivity to injustice indirectly, as the eighteenth century Swiss philosopher Johan Sulzer observed:

Wisdom knows about everything that man ought to be; it points the path to perfection and happiness which is related to it. But it cannot give strength to go down that often arduous path. The fine arts make the path smooth and adorn it with flowers which by their delightful scent, irresistibly entice the wanderer to continue on his way.

A shift in sensibility created by exposure to the beauty of Art operates unpredictably on ethical choices as, unlike a rational choice, shifts in sentiment rarely involve a decisive, eureka moment, when an argument is settled.

Rather, encountering beauty may lead to impulsive moral decisions based on heightened sensitivity, as where a person refrains from eating meat, when it does not ‘feel’ right.

Encountering a crowning achievement in music or poetry may awaken action in an apparently unrelated domain. Great music, and other Art, stills the mind, and engenders benevolence.

In divine rapture the poet builds a mythology out of imaginative materials located in Nature, and in the process incubates conventions and laws: ‘the poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world’ wrote Percy Shelley.

Percy Bysshe Shelley 1792-1822.

Firm moral convictions may bring a poet into conflict with temporal power, and demagogues appropriate and distort mythologies. The false poet, and prophet, appeals to the vanity of a sovereign.

A poet may feel compelled, nonetheless, to compromise with a patron – even a tyrant – to allow their work to reach fruition. In Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias’ the artist mocks a haughty ruler before posterity:

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

A true poet’s opposition to political power is, however, based on principle, not an anarchic reflex, and he may support a wise and just regime. For example, Dante favoured the Holy Roman Empire, as he saw a strong transnational authority as necessary to maintain peace in the Italian peninsula. A contemporary poet could support the notion of a European Community, or the United Nations, for similar reasons.

Poetry remains a vital commodity in any culture, foregrounding and guiding other artistic endeavours, channelling empathy, and forging justice. Defining its nature is elusive, and perhaps futile, but it is apparent that philosophers are increasingly drawn to its revelation.

It is not restricted to composition of metrical verse: any writer aspires to it. Alasdair MacIntyre writes: ‘Knowing how to go on and to go further in the use of the expressions of a language is that part of the ability of every language-user which is poetic. The poet by profession merely has the ability to a preeminent degree’.

Shelley saw poetry in metrical verse as being its ‘imperial form’, but recognised its presence elsewhere. ‘The parts of a composition may’ even be poetical, ‘without the composition as a whole being poetical’, he said. Poetry inhabits the best prose as a flow that carries a listener into the vision of the writer.

Poetry is perhaps best defined by what it is not, which is the everyday speech often imitated in novels and plays. It aspires to originality and even prophecy, as Aristotle says: ‘it is not the function of the poet to relate what has happened, but what may happen’.

It has an essential orality. Thus Yeats wrote: ‘Whenever one finds a fine verse one wants to read it to somebody, and it would be much less trouble and much pleasanter if we could all listen, friend by friend, lover by beloved.’

The Sacred Spring

Poetic language need not be extravagant, but the true poet is never entirely in control of composition. Thus Socrates complained that a man cannot accede ‘to the gates of poetry without the madness of the Muses.’ This seeming loss of consciousness in a deep flow state may lead to extravagant language, but this is unintentional.

Kathleen Raine points to the lofty style that distinguishes poetry from regular speech. She notes how Jung, who generally disliked high-flown speech, found that when what he called ‘mana, daemons, gods or the unconscious speaks in words its utterances are in a high style, hieratic, often archaic, grandiose, removed as it is possible to be from the speech of that common man the everyday self’.

Raine identifies this with a primal poetic impulse she encountered in the composition of folk songs: ‘The singing of the ballad was by no means in common speech. It was extremely slow, dignified and highly mannered’. She concludes that: ‘It is a mark of imaginative inspiration and content to write in a high and mannered style, removed from common speech; as it is of the absence of imaginative participation to write either in a conversational tone or to write in a deliberately vulgar idiom.’

Raine further opines that: ‘What was written for the sake of easy comprehension is precisely that part of poetry which becomes incomprehensible within a few years.’ This we find in the lyrics of most contemporary popular music, which sounds dated almost at the point of release.

On the other hand, today we see a widespread trend whereby difficulty is equated with quality. This may originate in contemporary economic structures, where many professional poets survive on government grants, and as academic specialists. Linguistic obscurity may be a cynical calculation, which contributes to a widespread, and tragic, alienation from poetry.

It appears to have a meaning and form internal to itself, beyond any individual poet. Jahan Ramazani observed, ‘time and again’, how poems, ‘reasserted themselves as poems even in the moments of seeming to fuse with their others.’

Similarly, when Dadaists and Russian futurists tried to fabricate new languages they found their imagined syntaxes led back to established moulds. Any poet travels a path overlaid with uncountable footprints guiding their course. The poem knows where it wishes to travel in the anticipatory stillness of creation. The great challenge in today’s digital fog is to encounter this tranquillity.

Poetry in Language

Many poets agree that composition is an ongoing revelation, conventionally attributed to the muse. But in the discussion of poetry there is perhaps too great an emphasis on individual genius, although the individual experience cannot be discounted.

We find in creation a dialectic between individual expression and the treasures hidden in all languages. The linguist Edward Sapir suggests that it is intrinsic to language every one of which ‘is itself a collective art of expression.’ He asserts that ‘An artist utilises the native esthetic resources of his speech. He may be thankful if the given palette of colours is rich, if the springboard is light. But he deserves no special credit for felicities that are the language’s own.’

Similarly Marcel Duchamp wrote: ‘Since the tubes of paint used by the artist are manufactured and ready made products we must conclude that all the paintings in the world are ‘readymades aided’ and also works of assemblage.’ The poet, however, renews and recasts these materials, sometimes bringing new colours to the palette, and reviving the use of others.

In some cases we find a mingling of tongues as new words enter languages in neologisms, as in Shakespeare’s heroic contribution to the English language. But this process is fraught with the risk of contrivance. Great poets are not necessarily polyglots, though they often are.

The expression of poetry should not be seen as an evolutionary display of verbal plumage, although troubadours will always seek to enchant. The German poet Rainer Maria Rilke firmly rejects meretricious verse. ‘Young man’ he warns:

it’s not about love, when your voice

forces open your mouth – learn to forget

your sudden outburst. That will run out.

True singing is a different breath. A breath

around nothing. A breeze in the god. A wind.

Rainer Maria Rilke 1875-1926.

The mythos of poetry is an intuitive response to life’s challenges, unconnected to the logos of philosophy, or scientific observation.

Its wisdom adds layers to a mystery lying beyond direct inquisition. ‘The abstract is not life’, Yeats wrote on his deathbed, ‘and everywhere draws out its contradictions. You can refute Hegel but not the Saint or the Song of Sixpence’.

The poet is never in control of the process of composition, and eminent authorities such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and John Milton have attributed inspiration to their dreams.

Charles Simic criticizes: the assumption … that the poet knows beforehand what he or she wishes to say and that the writing of the poem is the search for the most effective means of gussying up these ideas: if this were correct, poetry would simply repeat what had been said and thought before.’

Untuning the Sky

William Dryden, the first Poet Laureate, proposed in his Essay of Dramaticke Poesie that, ‘if natural causes be more known now than in the time of Aristotle, because more studied, it follows that poesy and other arts may, with the same pains, arrive still nearer to perfection’. Rather than affirming an alternative role for poetry, he was suggesting it should be informed by natural philosophy, as science was referred to until the 1830s.

In fact George Steiner observes a contrary trend: ‘Where the sciences, pure and applied, wherever mathematics came to map, to energize, to expand human experience and possibilities, the retreat from the word proved correlative and ineluctable.’

The greatest poetry looks beyond the real world of immediate perception and reinvents it, travelling at a different pace to the often linear progression of a philosophical argument. Thus the work of hundreds, or even thousands, of years ago may be compared with, and often exceeds in quality, the best available today.

The poetic vision arises from a sensitivity that sees the tears of a sycamore tree, as opposed to its biological classification. Nontheless, the greatest scientists – such as Alexander van Humboldt – have been animated by poetry, and poets, of course, do learn from science.

There are signs of stultifying premeditation as opposed to poetic vision, in Dyrden’s Grand Chorus to ‘A Song for St. Cecilia’s Day’ (1687), signalling the Final Judgement.

So when the last and dreadful hour

This crumbling pageant shall devour,

The trumpet shall be heard on high,

The dead shall live, the living die,

And music shall untune the sky.

The idea of music, which is the expression of harmony, signalling the end of days is troubling, and almost paradoxical. Samuel Johnson described this image as ‘so awful in itself, that it can owe little to poetry; and I could wish the antithesis of music untuning had found some other place’.

*******

A poet can be foolish, even sinister, without this undermining the aesthetic appeal of her work. Poetic ability does not equate with individual moral virtue. Posterity excuses the obnoxious behaviour and statements that are not intrinsic to the poetry itself, assuming Art to rise above the mundane, and that its beauty will engender justice.

Artistic censorship is a grave danger for any society, but in an era of free speech we may be facing greater dangers still, as George Steiner warns: ‘The patronage of the mass media and the free market, the distributive opportunism of mass consumption, could be more damaging to art and to thought than have been the censorious regimes of the past’.