If you are complaining about Climate Change, Brexit, Donald Trump, and all the cozening of late capitalism, I will not take you seriously if you have accepted, without very much thought, that there is only ever an arbitrary relationship between a signifier and what it signifies.

I will say to you that you are closer than you realize to being an embodiment of the world’s problems, and I will ask: have you considered how our future shall have been changed if the divine is awakened in man through poetry?

A widespread feeling of intellectual decrepitude among my generation is bound up with acceptance of the pseudo-philosophies that spread from France in the late 1960s. A dumbed-down account emerged in Terry Eagleton’s best-selling Literary Theory: An Introduction, now in its second edition.

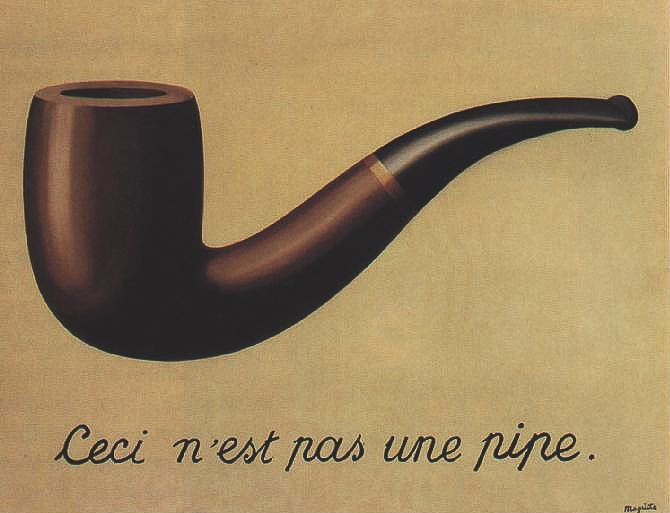

Each January I lecture on critical theory at Sarum College in Salisbury, and have grown increasingly frustrated outlining Jacques Derrida’s assumption of Ferdinand da Saussure’s argument that meaning in language is a simple matter of difference. In that lecture I explain – mostly to retired vicars or shamans, or both – that a sign is made up of a ‘signifier’ (like a written word) and a ‘signified’ (its meaning).

Then I quote from Eagleton: ‘The relation between signifier and signified is an arbitrary one’: there is no reason why the three marks c – a – t should signify cat. He continues: ‘Each sign in the system has meaning only by virtue of its difference from the others … meaning is not mysteriously immanent in a sign but is functional, the result of its difference from other signs.’

Such a theory may be correct from a strict scientific or linguistic perspective, but from a poetic perspective it is a negation. For W.B. Yeats, as for any other great poet, meaning is immanent in a sign. To disagree places functional rationality above a divinely creative imagination: perpetuating the potentially lethal metaphysical imbalance at the heart of our society.

In fact, Derrida can be a relatively exciting author, but I get the impression he is rarely read in the original, outside of France, and a simplified account of his work has become a dangerous dogma. It is now a political tool used in the academy to excuse people from teaching or studying the literary cannon: why would you bother with Shakespeare or Milton any longer? This is a New Age delinquency in desperate need of Reformation.

Eagleton further claims: ‘Poetry is a sort of trick, whereby an awareness of the textures of signs puts us in mind of the textures of actual things. But the relation between the two remains quite as arbitrary as in any other use of language; it is just that some poetry tries to ‘iconicise’ that relation, to make it appear somehow inevitable.’

I will counter Eagleton by quoting a more circumspect Romantic perspective than my own: that of the American poet Wallace Stevens who described the real as being constantly ‘engulfed in the unreal’. Poetry, he stated, ‘is an illumination of a surface, the movement of a self in the rock.’ Elaborating this belief, he knew:

A force capable of bringing about fluctuations in reality in words free from mysticism is a force independent of one’s desire to elevate it. It needs no elevation. It has only to be presented as best one is able to present it.

Great poetry makes you apprehend, more than cool reason ever comprehends, that there is a sacred bond between word and thing or word and idea, expressed in the very making of poetry, work which is, as Stevens imagined, ‘on the threshold of heaven’. A great poet should be capable of teaching a linguist to have faith in a ‘story’ that his discipline cannot fathom, so that it ‘grows’ in Shakespeare’s wise Hippolyta’s words ‘to something of great constancy; | But, howsoever, strange and admirable.’

George Santayana had asked: ‘How, then, should there be any great heroes, saints, artists, philosophers, or legislators in an age when nobody trusts himself, or feels any confidence in reason, in an age when the word dogmatic is a term of reproach?’ Stevens knew: ‘It is poverty’s speech that seeks us out the most. | It is older than the oldest speech of Rome.’ Meditating on Santayana dying in Rome, the poet apprehended the philosopher almost literally at the end of his poem: ‘He stops upon this threshold, | As if the design of all his words takes form | And frame from thinking and is realized.’

These works I have listed could be a kind of mirror. If you believe that the relationship between signifier and signified is an arbitrary one, you will see that you have a quasi-hipster beard and haircut, and that you are engaged to be married to an intellectual hippopotamus. The shepherd-king’s curse might stick:

For the mouth of the wicked and the mouth of the deceitful are opened against me: they have spoken against me with a lying tongue. They compassed me about also with words of hatred; and fought against me without a cause. For my love they are my adversaries: but I give myself unto prayer. And they have rewarded me evil for good, and hatred for my love. Set thou a wicked man over him: and let Satan stand at his right hand.

As René Guenon has warned: ‘The word ‘satanic’ can indeed be properly applied to all negation and reversal of order, such as is so incontestably in evidence in everything we now see around us: is the modern world really anything whatever but a direct denial of traditional truth?’ I am convinced that post-modern literary theory has Satan as its right hand man.

Edward Clarke’s last book was the Vagabond Spirit of Poetry. He is the Poetry Editor of Cassandra Voices. His poem Psalm 41 appeared in the previous edition.