The Catalan independence movement may seem like a throwback to a bygone age of nationalism. But the disproportionate reaction of Spain’s central government to the referendum in October has served, perversely, to make the break-up of the country more likely. Along with wider curbs on freedom of expression, the repression orchestrated by a ruling Partido Popular (PP) mired in corruption scandals, is an unsettling reminder of Franco’s long dictatorship (1939–75). Disturbingly, mainstream media and the judiciary are failing to check these trends.

E.M. Forster once remarked that if a choice came between betraying his country and betraying his friend, he hoped that he would have the courage to betray his country. Anyone who formulates such an opposition may be said to have no country if by that we mean: a sense of belonging to a broad set of principles identified with the state.

Thus, most Americans, notwithstanding their differences, submit to ideals of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’ expressed in the US constitution, which includes restraints on the excesses of presidential power. The appeal of belonging to a country declines when its government, even acting lawfully, becomes an immoral instrument of power.

George Orwell might have lost some friends if they had known he had provided a list of writers with Communist sympathies to MI5 in 1949. But he did so for the sake of friends he saw as countrymen, at a time when Stalin was in power in the Soviet Union.

Such dilemmas are rarely in black and white, or represent good versus evil. Even under the Nazis there were presumably, among others, nurses tending to the sick who played no role in the machinery of death and destruction. Under late capitalism states bear less responsibility than transnational corporations for destructive technologies, ecocide and grotesque inequality. State power and that of supranational institutions needs to be bolstered, but underpinned by transparency, representative democracy and accountability.

With large corporations exerting unaccountable influence, states, such as the Spanish, controlling public discourse and harbouring a compliant judiciary, may be tyrannical institutions.

The current impasse in Spain appears to be an old-fashioned conflict over national identity. Any nation, as far as most historians are concerned, is an imagined construct. ‘Imagined’, as Benedict Anderson put it, because ‘the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of the communion’. Nations loom out of an ‘immemorial’ past, generally based on dominant vernacular languages. A number emerged ascendant in Modern Europe from a stew of idiolects that co-existed in transnational empires, before the homogenising effect of Guttenberg’s printing press.

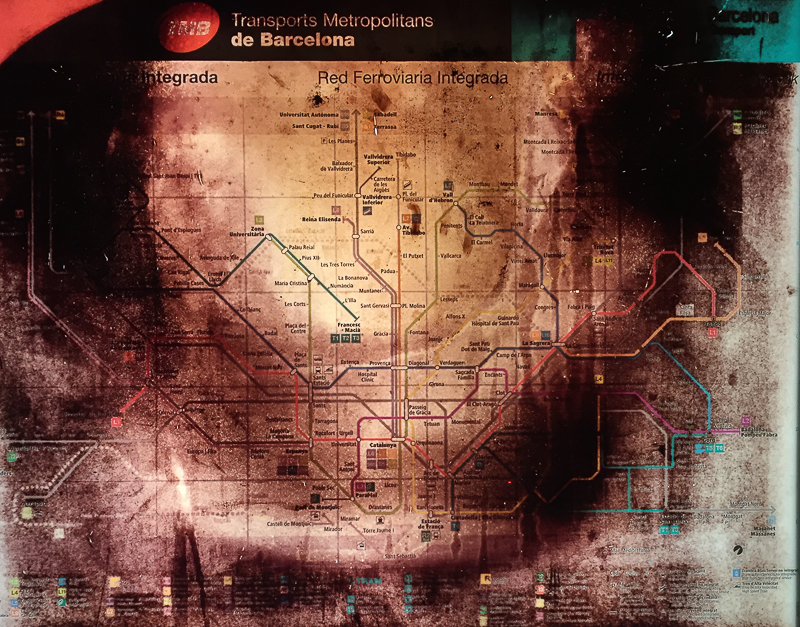

Image: Hector Castells

But language is not the only source of identity. An English speaker living in Wales may feel either Welsh, British or Muslim depending on the occasion. The particular identity selected to represent oneself shifts according to moods and settings, and can be stoked by demagoguery.

After observing the break-up of Yugoslavia in 1991 Michael Ignatieff wrote: ‘Consciousness of ethnic difference turned into nationalist hatred only when the surviving communist elites, beginning with Serbia, began manipulating nationalist emotions in order to cling to power.’ Today, we find Yugo-nostalgia among many Croats, Slovenes and Serbs who lament the dissolution of their historic friendship. “Nationalist hatred” is also the product of manipulation in Spain today, and appears to provide a smokescreen for corruption within the ruling Partido Popular (PP).

Once upon a time I knew Barcelona reasonably well, having rented an apartment there for a summer with friends after finishing university in 1998. In the days before euro-inflation the price of living was jaw-droppingly cheap, especially when it came to purchasing food in the colourful markets off Las Ramblas. Catalan was spoken widely, but we heard little talk of an independent state. Nonetheless, I was surprised by an assertion from one adult child of immigrants from another part of Spain that she was often made to feel a second class citizen.

Growing up in Ireland, I was accustomed to daily news bulletins reporting sectarian murders. This honed an awareness for potential divisiveness around identity. I have watched, therefore, with concern the increasing stridency of Catalan nationalism. The last time I visited Barcelona, two years ago, the streets were festooned with flags hanging from windows, amid rumours of intimidation of those who did not wish to participate. I could not help wondering whether separatism was a product of the region’s relative wealth compared to the rest of Spain: the region accounts for approximately sixteen percent of the Spanish population, but twenty-five percent of all Spanish exports. These pressures have increased in the wake of Spain’s economic crisis, culminating in Eurozone finance ministers agreeing to lend the country up to €100 billion to shore up its banks.

Image: Hector Castells

However, the jackbooted response of the Guardia Civil to the Catalan referendum in October, which left hundreds injured, has imperiled an often tempestuous relationship between Catalans and Castilians. The kingdoms of Aragon (essentially historic Catalonia) and Castile formed a political union in 1469 in the wake of the marriage of their respective monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella. Catalan has remained the lingua franca in the former Aragonese territory until the present day, although large scale migration there from other parts of Spain, and elsewhere, diluted this; just over half of its population appears to feel Spanish, based on the 2017 election results.

In the wake of the Nationalist victory of Generalissimo Franco in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), in which Barcelona played a prominent role on the Republican side, thousands were imprisoned and the Catalan identity was systematically undermined. During that long dictatorship (1939-1975) schools were banned from teaching the Catalan language and sources of Catalan identity whitewashed. With the introduction of democracy in 1975 a modus vivendi developed between Madrid and Barcelona – the Basque country became the nationalist flash point – until diminution in regional sovereignty in 2010 allied with the Economic Crisis gave rise to the current strife.

Iberian Peninsula 1400

Since the violent scenes in October many Spaniards have pointed to the illegality of the referendum to justify the conduct of the Guardia Civil, which makes neither moral nor legal sense. Editorials in the apparently liberal El Pais often refer to the Catalan leadership as ‘Golpistas’. The word ‘golpe de estado’ is the equivalent of coup d’etat or putsch, and implies that Catalan separatists have been using violent means to bring about independence, thereby justifying the thuggish scenes.

El Pais’ Managing Editor, David Alandete, remains obdurately unapologetic, likening Catalan separatists to Far Right extremists: ‘This is the exact same situation as The New York Times under Trump, the UK press under Brexit, German press under Alternative for Deutschland’. Like most established print media around the world, El Pais has experienced significant financial troubles in recent times. John Carlin, a sacked former columnist has argued that the parent company Prisa reflects the wishes of Madrid’s political class.

Catalans might justifiably wonder whether their national friendship with Castile can withstand the failure of mainstream media and television to hold its government to account, and provide a reasonable witness to the events. To compare Catalan separatists to Alternative fur Deutschland is a gross distortion.

How has this all came to pass? We are living in a European Union which guarantees free movement of labour and capital, and Spain has been a democracy for over forty years. There are certainly heirs of Franco who want to impose linguistic and religious homogeneity on the rest of the country. Individuals with connections to the lay Catholic organisation Opus Dei exert what many consider an unhealthy influence over the Spanish cabinet, but the PP holds power without a majority in the Cortes.

We appear to be witnessing a sophisticated distortion of reality, where crucial components of the media have been co-opted into serving the interests of a governing elite now mired in economic scandals. This is not to say that the Spanish media is a monolith: reports continue to emanate from sources including El Pais furnishing evidence of government impropriety. But when it comes to reporting on the burning issue of Catalonia keen observers claim that balance has been lost.

One disturbing hypothesis is that polarisation is actually Spanish government policy, permitting a slide towards centralised, autocratic rule. As A. Reynolds put it in his recent article for Cassandra Voices: ‘Spain remains to a large extent a liberal democracy, but there’s an unsettling authoritarian trend, which is being orchestrated by its main conservative party.’

Oppression of Catalan separatism is part of a wider draconian policy, extinguishing civil liberties, aimed at perceived enemies of the people. This month the Spanish Supreme Court upheld a three-and-a-half-year prison sentence against rapper Valtonyc, for lyrics deemed offensive to the monarchy and supportive of terrorism. The court’s contention that the lyrics of the Mallorcan native represented an incitement to terrorism are implausible, especially considering he refers to the Basque separatists ETA, who have been in permanent ceasefire since 2011. The wholly disproportionate sentence – the same week a man was sentenced to two years for paedophilia in Palma – simply draws attention to his songs, one of which has had almost a million hits on YouTube in the wake of this latest miscarriage of justice.

Enrique López, one of the judges in the 2014 High Court case, offered the following rational for his decision: salvar la democracia de sus enemigos, aunque sea sobre la base de redefinirla como disciplinada o autoritaria: ‘to save democracy from its enemies, it may be necessary to redefine it as disciplined or authoritarian’. He was referring to the German concept of Streitbare Demokratie, ‘well fortified’, or ‘battlesome democracy’, used to justify extreme measures against extremists who wish to dismantle democratic institutions. To compare Catalan nationalism to Neo-Nazisism is another perverse distortion, legitimating the most appalling excesses. If Lopez’s approach was accepted through history, the world would still be made up of empires.

Ironically López himself was forced to resign from the bench in 2014 after being found driving with blood alcohol levels six times above the legal limit. He is aligned with the PP, and now laments that separatists parties cannot be banned.

The playwright and poet Federico Garcia Lorca was shot by nationalist militia in 1936. By then he had written his eerily-familiar ‘Ballad of the Spanish Civil Guard‘ (1928) which begins:

The horses are black.

The horseshoes are black.

Stains of ink and wax

shine on their capes.

They have leaden skulls

so they do not cry.

With souls of leather

they ride down the road.

Hunchbacked and nocturnal

wherever they move, they command

silences of dark rubber

and fears of fine sand.

They pass, if they wish to pass,

and hidden in their heads

is a vague astronomy

of indefinite pistols.

…

(translated by A.S. Klyne)

No doubt these words of Lorca still offend certain Spanish sensibilities, and could conceivably land a poet in jail if he wrote them today.

Furthermore, an exhibition called ‘Political prisoners in Spain’ has recently been shut down by the authorities in Madrid, while a book about cocaine smuggling in Galicia which mentions a PP mayor originally convicted for involvement, but absolved on appeal, has been banned.

As with Valtonyc’s case, keeping these subjects from public attention does not appear to have been the primary purpose of the censorship. We live in the age of the Internet. The BBC exhibited the photos to the world and the book was soon selling ten copies a minute on Amazon. It seems to be part of a wider policy of drawing battle lines between patriots and traitors, which takes the sting out of ongoing prosecutions imperiling the PP elite.

Financial irregularities also feature in the affairs of politicians from the PDeCAT, the centre-right party of the Catalan bourgeois, and historical ally of the PP, who are late converts to the independence cause. But the number of PP politicians that have been investigated for corruption in recent times is staggering. This includes a scandal involving a large number of high level PP politicians in Valencia in 2016.

Notably, in this region, neighbouring Catalonia, Valencian, a dialect of Catalan, is widely spoken. The kingdom of Valencia was historically within the realm of Aragon. Although Valencians have always been wary of the big brother in Barcelona, a discredited PP could leave room for the ‘contagion’ of Catalan separatism to spread. The distraction of a confrontation with Barcelona takes the heat off corrupt officials.

It is also instructive that the Valencia branch of the Popular Party (PP), under the leadership of one-time premier Francisco Camps, played a determining role in ensuring Mariano Rajoy’s survival at the helm of the national party in 2008, when he lost a general election for a second time to the Socialist Party. Ever since, Rajoy has offered stout defence to a supporter who was at the helm of a region that became a byword for corruption.

Corruption is far from being restricted to the provinces. The Madrid branch of the PP was raided in connection with the Púnica ring, also in 2016, which is alleged to have unlawfully awarded as much as €250 million in public contracts to beneficiaries in return for bribes. The origin of the Operation Púnica investigation was the discovery of Swiss bank accounts held by, among others Francisco Granados, once the right-hand man to Esperanza Aguirre the former President of the Madrid region. It is telling that Swiss banking authorities, rather than an internal investigation, reported: ‘aggravated money-laundering operations’. This compelled an investigation leading to a trial in 2017 involving 37 suspects.

Franscisco Correa, a businessman at the heart of the scandal allegedly liked to be known as ‘Don Vito’, after the character played by Marlon Brando in The Godfather, making his protestation that he did not realise he was committing any crimes ring rather hollow.

The confrontation between Barcelona and Madrid has been brewing for some time in a football-obsessed country. Rather than acting as a lightening rod to diffuse tensions, the morbo rivalry between Real Madrid and Barcelona FC fuels hatred. The success of Barcelona infuriates Madridistas, and vice versa, explaining the outlandish sums both sides began to spend on players, even as the Economic Crisis was in full swing.

It also might explain why the former Barcelona manager Pep Guardiola, a supporter of Catalan separatism, has been harassed by the Spanish authority. His private jet was boarded by police, apparently in search of exiled former Catalan leader Carles Puidgemont. Also, a car in which Guardiola’s ten-year-old daughter was travelling was stopped and searched by Police.

Sides are being chosen. The apparently centrist Ciudadanos which claims to disavow nationalism is increasingly eager to assert its ‘Spanish’ credentials. The leader of that party Albert Rivera was recently photographed with a Spanish flag wristband, which was hardly an unintentional gesture. He has also expressed the uncompromising view that ‘putschists can never be part of any negotiation‘, sticking to the falsehood that separatists are violent insurrectionists. The Spanish Socialist Party have been similarly spineless, supporting the ban on the recent exhibition on political prisoners.

Image: Hector Castells

Spain is still coping with the legacy of the Economic Crisis, and the introduction of the euro which substantially drove up the price of living. Youth unemployment now stands at levels close to 50%, and entrenched poverty co-exists with fabulous wealth. Populist nationalism, on both sides, distracts attention from day to day concerns, cloaking the real inequities and corruption at work. But the authoritarian sentiments expressed by politicians and judges associated with the PP are especially worrying. The idea they are defending democracy represents an Orwellian inversion.

Fellow Europeans must pay greater attention to the erosion of civil liberties and the Rule of Law in Spain, perhaps registering their disapproval by avoiding travelling and doing business with Spanish regions that support the PP. Pressure can be brought to bear on home governments to isolate the Spanish government in Europe, until negotiations begin and liberation of political prisoners occurs. Perhaps the territorial integrity of Spain can still be saved: national break-ups are rarely achieved without significant bloodshed, and often regretted afterwards. After all, as Samuel Johnson noted: ‘patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel’.

Frank Armstrong is the Content Editor of Cassandra Voices. You can find an archive of his published work here.

Feature Image: Hector Castells