THE LONG READ: Ireland is neither a totalitarian state, nor even a dictatorship. Nonetheless, the propaganda of an economic elite has forged a dominant consensus, in which two centre-right parties compete for power. Across a print media duopoly and national broadcaster well-honed techniques of social control divert attention and sow confusion, while subtly instilling dogmas. The education system also plays a vital role in propagating social norms and channelling aspirations. The dominant consensus is not doctrinally extreme or even illiberal, at least by international comparisons, but it insulates embedded wealth in the form of land and property from taxation, stimulates demand for mortgages among the young, and protects the farming sector from environmental oversight.

I – We have ways of making you think…

As Nazi Germany’s Minister of Propaganda, Josef Goebbels had one major difficulty: a taste for dark-haired beauties. His marriage to the perfectly-Aryan-looking Magda (with whom he would later ‘loyally’ commit suicide inside Hitler’s bunker in 1945, after they first murdered all six of their sleeping children) became a sham. Poor Josef could not help taking advantage of the brunette actresses over whom his role effectively gave dominion, controlling movie sets that were a Harvey Weinstein paradise. In particular, Goebbels conceived a passion for a Czech – untermensch – beauty Lída Baarová, which almost drove him to end the marriage in 1938. Hitler himself intervened demanding his propaganda chief remain with his wife and children. The mask concealing the hypocrisy could not be allowed to slip.

Despite occasional differences of opinion, Hitler realised that Goebbels was crucial to the smooth functioning of the Third Reich. While Leni Riefenstahl delivered innovative blockbuster effects, Goebbels genius lay in delivering subtle cues, released under a comfort blanket of light entertainment. Goebbels saw maintaining a feel-good factor as the essential role of propaganda. He did not even care to see der Fuhrer appear in cinema news reels. In a totalitarian society a subservient people should not be over-exposed to politics.

He had immersed himself in the golden era of the silver screen, expressing particular fondness for the 1937 Disney classic ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’. Overtly political films were not only useless but also counterproductive he believed. The depravity of ‘the Jew’ should be integrated into pictures which carried an audience along, such as the lively 1940 ‘historical’ drama Jud Süss, ‘Jew Suss’. This contrasted with the heavy-handed style of Der Ewige Jude (1940) ‘the Eternal Jew’, directed by Fritz Hippler that depicted Jews alongside rats inside the Warsaw Ghetto. Goebbels correctly predicted this would bomb in the box office.[i]

Light entertainment diverts, as does outright nonsense, which George Orwell referred to as ‘Duckspeak’ in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, published in 1949. Its effect is to lower the intellectual level of conversation, spread confusion and allow the speaker to evade responsibility: a tactic increasingly familiar in our era of ‘post truth’. In the novel the official language of Oceania is overtly-propagandist Newspeak, but Duckspeak’s capacity to accommodate contradictions, even midway through a sentence, was much valued by the ruling regime.

There are societies such as North Korea’s, or previously Mao’s China when children informed on their parents, where freedom of expression is almost completely eradicated and replaced with Newspeak – and probably Duckspeak – to such an extent that individuality is effectively extinguished. One result is a severe lack of economic dynamism. Market economies, however, require freethinking innovators in order to thrive; a small resistance movement even survived in Nazi Germany because Newspeak had not entirely permeated that society. ‘Hard’ propaganda – or Newspeak – is thus only of limited value. Instead, the ‘soft’ propaganda of light entertainment and, increasingly, Duckspeak – including the obfuscation by politicians who ‘duck out’ of answering questions – is more generally deployed to support indispensable fictions in liberal democracies – like the canard of opportunity-for-all. Moreover, even in democratic societies educational filters screen for obedience.

Variants of these influences can be identified in Ireland, where great wealth subsists alongside grinding, long-term poverty. Irish society is generally tolerant, but growing inequality is unraveling the social fabric, and creates conditions for the scapegoating of minorities.

II – Ireland’s Two-Party System

Foreign multinationals are a transient presences on the Irish scene. Their indigenous handlers, an aging cohort of predominantly male, property-owning, car-driving, privately schooled, health-insured professionals – lawyers, accountants, doctors, financial service providers and other high-earning business people – are the enduring economic elite of the state. Its dominant consensus does not emerge from smoke-filled rooms any longer. Rather, it is an aggregate conception of what a ‘normal’, self-interested person of this class aspires to. Indeed, those upholding what is a neo-liberal orthodoxy may be unaware – like Ebenezer Scrooge – of its detrimental effect. What is an often passive propaganda is expressed through a media dependent on advertising revenue, and in the policies of the two largest political parties.

A recent poll showed seventy percent of the highest (AB) social class support one or other of the two main centre-right political parties, in particular Fine Gael (Irish Times MRBI poll, October 16th, 2018), now the ‘natural party of government’ for the dominant interest.

The ‘bricks and mortar’ of property remains, overwhelmingly, their preferred asset, with many acting as landlords. Thus, according to economist David McWilliams the wealthiest top five-percent in the country own over forty percent of its wealth, with eighty-five per cent of that held in property and land. The key objective of Irish propaganda, and we may call it that, is therefore to keep the economy on an even keel of steady growth, and rising rents, while ensuring that wealth, mostly property, is subjected to minimal taxation. The result is that in the last financial year a mere €500 million out of total tax receipts of over €50 billion, derived from land or property.[ii]

The dominant consensus also insists that it is necessary to keep a lid on government expenditure on public services (most of which the elite does not use), so as to avoid the over-heating of Bertie Ahern’s ‘boomenomics’ before the crash of 2008. Then low taxation on income and wealth went hand-in-hand with spending increases, and public sector salary ‘benchmarking’ with the private sector. The ineptitude of these policies were partly to blame for a property bubble before the crash of 2008, and has consigned Fianna Fáil to its present subaltern role, in which it now flaunts a more centrist approach.

In a clear signal to the economic elite, Minister for Finance Michael Noonan launched his Budget 2016 claiming the days of ‘boom and bust’ would be consigned to the history books.[iii] Throughout his tenure (2011-2017) no serious public housing initiatives were embarked on. In 2015, for example, by which time economic growth for the year was at 7.8%, a mere 334 social and affordable units were built.[iv] The ensuing scarcity ensured a dramatic recovery in property prices, including that held by the state bank NAMA.

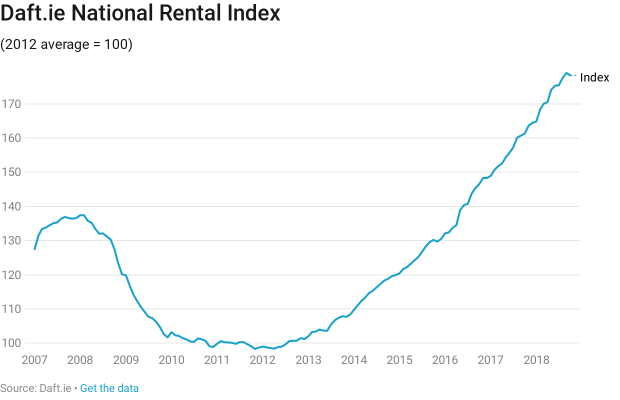

Another salient feature of Irish propaganda is the essential delivery of buy-in from young adults, who continue to purchase property at inflated prices. Prior to the crash Dublin prices soared to such an extent that a residence in the city became more expensive than New York or London.[v] Dublin prices are set to reach boom-time levels this year according to Pat Davitt, head of the Institute of Professional Auctioneers and Valuers (IPAV), with an average family home costing over half a million euros.[vi] Meanwhile average Dublin rents now exceed the heights of the Celtic Tiger by thirty percent. This means those landholders, and institutions, that weathered the recession have seen huge dividends.

Source daft.ie

Any new property purchaser instantly becomes a stakeholder in the dominant consensus. The buy-in of upwardly-mobile youth not only maintains market demand, but also brings political support for the dominant consensus. Political parties threatening the ‘stability’ under the centre-right axis are subtly undermined as the ‘loony’ left and not given a platform in the mainstream media, or co-opted into governing coalitions and discredited, as was the case with Labour, the Greens and now the Independent Alliance.

Importantly, up to fifteen percent of the population are foreign-born nationals. Apart from UK nationals, they do not enjoy a right to vote in general elections, unless they take out Irish citizenship, costing almost one thousand euro. Unlike native-born Irish, who historically had among the highest rate of private home ownership in the world, peaking at 80% in 1991, (declining to 71% in 2011),[vii] many come from countries where renting for life is the norm, and may not wish to reside here long-term. Politically, this large cohort only exerts influence via multinational employers, who face demands for wage increases due to spiralling rents. At the bottom of the ladder are unskilled (or at least unqualified) non-EU migrants – gastarbeiter – many of whom are on short-term- (often student-) visas, and permitted to remain in the country only insofar as they serve an economic purpose.

III – The Crucial Constituency

The elite’s longstanding hold on power, via the two main political parties, relies on a crucial constituency of farmers and their extended families, who are evenly distributed throughout the state, apart from Dublin. Although continually declining in number, they are overwhelmingly native Irish – thus enfranchised – vociferous campaigners, and of a vintage that tends to vote. This ensures their supposed interests, more accurately those of comprador multinationals that trade their commodities, are protected by Irish propaganda.

A remarkable eighty-percent of farmers, working on almost eighty-five thousand separate farms, support either Fine Gael or Fianna Fáil according to the aforementioned poll. The former are especially reliant on their allegiance, which means the national (and global) interest in reducing GHG emissions in order to avoid up to €600 million every year in EU fines after 2020 may be overlooked.[viii] Agriculture produces almost a third of total national emissions, yet contributes a mere 1.7% of carbon taxes.[ix] The farming sector is, however, an increasingly fragile alliance, with the average annual income on dairy farms approximately €85,000, but averaging only €15,000 on the average dry cattle (beef) farm, all of which, derives from subsidies.[x]

An urban working class of unskilled, semi-skilled and unemployed, has been mollified by comparatively generous social welfare payments, but is increasingly impoverished by the scarcity and cost of property, rising rents, and a failing system of public health. Eighteen to twenty-five-year-olds are discriminated against by lower social welfare payments, but tend not to turn out for elections, and are inclined to emigrate, so can easily be ignored.

Preserving a share of working class support remains important, in terms of optics at least, for the two main political parties, especially Fianna Fáil, which preserves the charade of being a party for all classes. Unlike farmers, however, historically a working class consciousness has not been evident in Ireland, and approaches to the national question and moral or religious concerns have tended to sway this cohort. Also, while farmers have clear objectives in terms of maintaining a subsidy regime, and avoiding environmental regulation, the working class is more easily distracted from establishing fixed political aspirations.

The widespread protests over water charges in 2014 were one of the few occasions when the dam broke, and working class discontents spilled onto the streets. But this single issue could be conceded, and sustained engagement with politics avoided. Yet, according to Social Justice Ireland, last year 790,000 people were living in poverty, of whom 250,000 were children.[xi]

Similar to farmers, most civil service workers, including senior teachers, have been kept on side with generous pay and conditions. Teaching salaries averaging over $60,000 per year compare favourably with other OECD countries. As with the social welfare system, new entrants have been discriminated against, with many being forced to emigrate during the crash, but they count for less politically than their senior colleagues. The current modus vivendi between the teaching unions and the ruling parties is reflected in the terminal decline of the Labour Party, their traditional voice in the Dáil.

The new Minister for Education, Joe McHugh, recently described secondary teachers as being overburdened by ‘initiative overload’[xii], which might come as a surprise considering they enjoy more than sixteen weeks of holidays per year, and curricula that have changed little in decades. Secondary school teachers play an important role in upholding the dominant consensus.

The spiral of inequality, globally and nationally is, however, accelerating, and the coalition of interests maintaining the dominant consensus is unstable. Multinationals siphon off vast profits from a market one Tesco executive allegedly referred to as ‘Treasure Island’, with consumer prices, on average, twelve percent higher than in the UK,[xiii] while some avoid corporation taxes altogether. Meanwhile the state labours under a debt of over €200 billion after a bailout the terms of which (including the creation of NAMA) protected the interests of those members of the economic elite that did not speculate wildly prior to the crash – such as former solicitor Brian O’Donnell who was evicted from his Dalkey home in 2015 – while working to the detriment the poor, and the impressionable young who had been encouraged to take out crippling mortgages.

The Irish economy is vulnerable to global financial shocks – with just fifty large firms accounting for three-quarters of all exports[xiv] – a recrudescence of nationalism after Brexit, and the growing obsolescence of many forms of work, including our current farming model. The economic elite is intellectually rudderless, and only knows the way of economic growth-without-end, where ecological constraints are ignored, and in which the retail cartels make a mockery of the notion of a free market. The centre-right cannot hold for long, but in the meantime, the wheels of Irish propaganda keep turning.

IV – The Propaganda Model – Education

State secondary school pupils are encouraged to take subjects that will prepare them for work in multinational corporations, with an emphasis on science and technology, rather than arts, humanities or social sciences. Philosophy is unavailable as a secondary school subject, while history has been downgraded in recent years.

In the state school system, which I observed as a supply teacher, rebellious students are removed from obedient peers and housed en bloc in ‘pass’ classes, or entire schools, which are little more than advanced creches, or holding facilities. There behaviours and performances deteriorate in the absence of positive role models. Ill-equipped for work or even social life, the dole queue awaits, or worse. Importantly, this underclass is unable to articulate their grievances – one in six of the adult population is functionally illiterate.[xv]

The essential breeding ground of the economic elite is found in the paradoxically state-funded system of private education, in which the state pays the salaries of teachers – costing around €90 million per year. This ensures a private education is not prohibitively expensive, broadening the base of the elite, with over twenty-five thousand students enrolling in 2017.[xvi] In these institutions lasting ties are formed, and the best preparation for the Leaving Certificate offered, which is generally a code to be cracked. Behavioural problems among middle class students are less pronounced, in my experience, but where rebelliousness, or just a lack of conformity, is apparent authorities employ long-standing methods of control. The sport of rugby emphasises the collective in a test of manhood, with dissenters often subjected to homophobic slurs.

As far back as the 1920s, one of the leading Dublin Catholic secondary schools for boys of its time, O’Connell School on North Richmond Street, recommended its pupils in the following terms: ‘Your ‘Richmond Street’ boy makes a good official. In the first place he possess the necessary academic qualifications to place him high on the examination lists. He has, in addition, certain qualities which make him a good colleague. However clever an official he may be, he has to pull with the team.’[xvii] Little has changed in a hundred years. The abiding ambition of most all-male private schools remains not only examination results, but also to develop a cast of mind disposed to “pull with the team”, while instilling an idea of what is ‘normal’ in the dominant consensus.

Widespread single gender education keeps more troublesome and sports-obsessed male adolescents apart from females, who streak ahead academically. But when both enter the workforce, the demands of motherhood generally count against women working the long hours necessary for career advancement in most of the elite professions. ‘Early-rising’, workaholic male professionals are the praetorian guard of the dominant consensus.

Irish class boundaries are not impermeable, or based on race or creed – as Leo Varadkar’s background illustrates – but it is increasingly difficult for anyone who is not from an elevated social background to rise up through the educational ranks to become a lawyer, doctor or even a banker. For example a young barrister, after a minimum of four years full-time study, is required to work without a salary for a further two, while he ‘devils’ under a senior colleague, thereby excluding a large proportion of the population. That profession is the bulk supplier of the country’s judiciary, which goes some way towards explaining the Court’s historic deference to property interests – notably: In the matter of Article 26 of the Constitution and in the Matter of The Housing (Private Rented Dwellings) Bill, 1981.

Privileged classes, nonetheless, still produce offspring with intellectual or artistic aspirations that survive the stultifying educational system. As the economic benefits of the humanities and arts are now grudgingly recognised these pursuits are indulged with financial support available from state and private sources, albeit generally via laborious application processes. Ideally, however, the ‘creative’ is an advertising executive. Due to high rents, artists are pushed into becoming ‘art-repreneurs’, and conscripted into marketing the state as a place to do business.

Academia once offered a platform for meaningful critiques of Irish society, but little interaction with the public now occurs, as excessive specialisation has brought abstraction to most subjects. As in other countries, young academics are required to ‘publish or perish’ prolix articles addressed to their peers, leaving little time for political engagement. In 2012 Tom Garvin, Emeritus Professor of Politics decried the dismantling of prior ‘semi-democratic’ structures in University College Dublin, claiming: ‘internal representative structures and freedom of speech were closed down and replaced with Soviet-style top-down “councils” that passively received and passed on instructions from on high’. As non-academic staff began to outnumber academics Garvin found ‘an indescribable grey philistinism’ characterise the public culture of the college ‘and a hideous management-speak’ drowned out ‘coherent communication.’[xviii]

IV – The Propaganda Model – Print Media

The Irish media is subject to global trends, but also internal dynamics. The reputation of journalists as crotchety, difficult people, so often depicted on screen, belies how most now “pull with the team”, or see their careers stall. The journalist that questions dominant consensus is depicted as a conspiracy theorist, but this cautionary distrust of authority now appears to be in short supply. Print media in Ireland is on its knees as young readers, in particular, opt for online content, which has resulted in significant redundancies. Precarious freelancing is the norm for new entrants.

Denis O’Brien – who a tribunal of enquiry in 2011 concluded had handed over hundreds of thousands of pounds to a government minister, who it was ‘beyond doubt’ had given ‘substantive information to him, of significant value and assistance to him’ in securing a mobile telephone licence[xix] – controls a great swathe of Irish media, including the Irish Independent, the Sunday Independent – the widest-circulating daily and Sunday newspapers – thirteen regional publications, commercial radio channels, Newstalk (the Orwellian association seemingly lost on them) and Today FM. O’Brien’s outlets are generally pro-business, or more accurately pro-multinational, and often critical of the institutions of the state and even individual ministers, but generally support the economic elite with selective regurgitation of government Newspeak.

For example, the headline of the Irish Independent on October 18th 2018 ran: ‘Varadkar’s Government in crisis after one minister resigns, another faces fight for survival.’ The article simulates the drama of Fianna Fáil calling time on the coalition, thereby maintaining the fiction of two opposing forces – or only two options in the event of an election. The dominant consensus is woven into the piece with the reminder: ‘The instability has created a major crisis for the Government after a Budget that was well received by most sectors’. In contrast, Social Justice Ireland argued that the budget disproportionately benefited high-earners, noting: ‘Budget 2019 fails to make any notable impact on Ireland’s entrenched inequalities and fails to tackle any of the major challenges the country currently faces.’[xx]

The ‘Indo’ also ostentatiously stimulates demand among upwardly-mobile youth for property and health insurance. Thus the headline on the 19th of October 2018 read: ‘Families to save in home loan and health shake-up’. Its consumer affairs correspondent announced: ‘Families are to enjoy the benefits of a price war in health insurance, and increased competition with even more entrants into the mortgage market’. Mostly, however, it provides the mainstays of effective propaganda: light entertainment, especially blanket sport coverage, celebrity gossip and sexual titillation.

There is only one other genuinely daily national indigenous newspaper – the Irish Times – which has hoovered up the Irish Examiner and regional titles to create a duopoly. It is considered, and styles itself, ‘the paper of record’, but rarely conducts meaningful investigations, tending only to print sensitive material once it has been aired elsewhere, such as when reporting on the harassment of employees by Michael Colgan, the former director of the Gate Theatre.[xxi] The catastrophic purchase of www.myhome.ie at the height of the last boom makes it a vested interest in the property market, which is reflected in extensive property supplements. Often seen as a bastion of Irish democracy, its credibility was undermined by the hosting of unmarked advertorials of the government’s Project Ireland 2040 plan.[xxii]

The imprint of government Newspeak was also evident on October 13th, the morning before the last budget was announced, with the headline ‘Significant spending increases for housing and health’ emblazoned across the front cover. Importantly, it gave a positive spin on the budget, which could be seen from every newsstand in the country, ensuring, even if the paper itself was never read, it maintained the ambient feel-good-factor. Was the positive spin provided as a quid pro quo for the scoop, or strategic leak?

The fingerprints of the economic elite are also apparent in the opening words of an article by chief political reporter Pat Leahy on October 14th. He cautioned the following: ‘First, do no harm. Any finance minister should heed the primary precept of the Hippocratic oath, and ensure that their fiscal and economic prescriptions do not damage the Government, or the economy.’ “Doing no harm” appears to involve upholding the dominant consensus, and avoiding the issues of social exclusion and sustainability.

The ‘Old Lady of D’Olier Street’ still provides a platform for left-leaning and progressive journalists, including Fintan O’Toole, Una Mullally and David McWilliams, but this does not imply relentless focus on Ireland’s economic and social structures. Their emphasis has tended to be on identity politics, issues of individual liberty, particularly reproductive rights, gender equality, and from O’Toole the ongoing dramas of Trump and Brexit. Only McWilliams consistently nails the social structures. Ultimately, the paper cannot afford to affront AB readers or farmers with ‘shrill’ left-wing commentaries or sustained campaigns, but in keeping these writers on board it maintains the illusion of being progressive.

It has also dumbed-down considerably recently in the face of ‘commercial realities’, in other words a high salary overhang. Stodgy book reviews have been marginalised, with increasing emphasis on business, vox pop reporting –with leading articles like ‘Life on the Luas: a tale of two tracks’[xxiii] – consumer affairs and, as usual, lavish sport coverage: all of these fit with the propaganda model of distraction with light entertainment.

We have relied on UK publications to break stories such as labour abuses in the fishing industry, the substitution of horsemeat for beef, and the recent scandal of unmarked government advertorials. Serious interrogation of the role of the Gardaí has been conducted at a remove from the mainstream.

Two political magazines, The Phoenix and Village Magazine, offer satire and dissent, but the former is not available for free online and thus has limited political clout. The latter is yet to develop a viable commercial model, but at least upheld freedom of expression and Dáil privilege by publishing online (along with www.broadsheet.ie) a record of Catherine Murphy’s speech accusing Denis O’Brien of corruption, after he had taken out an injunction against RTÉ, and when the Irish Times took fright.

VI – The Propaganda Model – the State Broadcaster

The state broadcaster receives a compulsory licence fee from anyone with a television set in the country, but still depends on advertising revenue to remain financially solvent. Like the Irish Times, RTÉ is a broad church, but both TV and radio stations are awash with light entertainment, including vox pop phone-ins like Joe Duffy’s Liveline which also offers an outlet for nonsensical Duckspeakers, while Ray D’Arcy and Ryan Tubridy provide distraction throughout the day on the news and current affairs channel RTÉ Radio 1.

Tubridy is Ireland’s highest-paid broadcaster, and often its public face as host of the prime time, Friday night ‘The Late Late Show’. A scion of a well-known Fianna Fáil family, he has assumed a seemingly unassailable position, and rarely courts controversy; although he recently suggested that people who (legally) cycle two abreast should be ‘binned‘,[xxiv] and once compared breastfeeding in public to urinating on the street.[xxv] Mostly however he tugs at the heartstrings of viewers, while devoting his spare time to writing children’s books.

RTÉ mostly anesthetises the population with light entertainment, especially sport – one recent survey showed that on ‘Morning Ireland’, the highest-rating radio show in the country, environmental stories were covered for only 0.92% of the time, whereas sports news accounted for 12.41% of content.[xxvi] Elsewhere, shows such as ‘Claire Byrne Live’ offer a small screen outlet for Duckspeak. At the end of one episode last year, during which evidence for human-influenced climate change was ‘debated’, thirty-four percent of respondents did not believe this would pose a serious threat in their lifetimes, while nine-percent did not know.[xxvii] Damien O’Reilly has also provided an outlet for Ryanair boss Michael O’Leary to express the Duckspeak of climate denial,[xxviii] the farming lobby no doubt delighted by this muddying of the waters.

What passes for news and current affairs coverage generally consists of assessments of Tweedledum and Tweedledee politics, or commentaries on controversies stirred up in the print media. A case in point was in the recent presidential election when the previously unknown, and unsupported, Peter Casey made a demeaning remarks about Travellers, which was greeted with such ‘outrage’ that he became a serious candidate in the election, thereby providing plenty of fodder for Joe Duffy, and others.

Ironically, the most serious political critique is found in the weekly comedy show ‘Callan’s Kicks’, where a degree of latitude is permitted. But as Theodore Zeldin explains, comedy can actually have the effect of reinforcing conformity ‘by being its safety valve’. Zeldin points out that carnivals, such as the medieval festival of fools, ‘have throughout history made fun of authority, and turned hierarchy upside down’, but ‘did so only for a few days.’[xxix]

*******

Ireland is a free country without an oppressive secret police force systematically monitoring communications. Despite the chilling effect of current defamation law, freedom of expression is enshrined in the Constitution and European Charter of Human Rights. Nonetheless as George Orwell put it in his proposed preface to his 1945 novel Animal Farm: ‘Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban.’ Orwell observed how:

At any given moment there is an orthodoxy, a body of ideas which it is assumed that all right-thinking people will accept without question. It is not exactly forbidden to say this, that or the other, but it is ‘not done’ to say it, just as in mid-Victorian times it was ‘not done’ to mention trousers in the presence of a lady. Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness. A genuinely unfashionable opinion is almost never given a fair hearing, either in the popular press or in the highbrow periodicals.

Irish propaganda upholds a dominant consensus: preserving low taxation on wealth, especially property; encouraging steady economic growth, including rising rents; maintaining buy-in from young property purchasers; and insulating the agricultural sector, often referred to as ‘our farmers’ on the state broadcaster, from criticism. This is achieved through straightforward manipulation of the media as well as instilling conformity through the education system, but also in the use of light entertainment, especially sport, as distraction, as well as in the peddling of plain nonsense, on RTÉ especially. With the advent of social media we are seeing new and sinister methods of achieving these objectives, which this article has not addressed, but which Ireland is not immune from.

The relatively new medium of the internet need not necessarily be feared however. It can, even through increasingly compromised social media, counter propaganda, by allowing like-minded individuals to converge and orchestrate campaigns. Propaganda can easily be exposed and alternative viewpoints expressed. But we must guard against its capacity for offering further light entertainment distraction, and platforms for madcap Duckspeakers.

The most important weapon against propaganda is education, both childhood and lifelong, which must address adult illiteracy. A priority should be reform of that sector in Ireland: first by ending subsidised private education; then placing greater emphasis on the enquiring humanities and arts, before addressing the decline of higher learning institutions.

The water charges campaign failed to generate long-term political engagement among the working class, or an increasingly squeezed middle. Representatives of the economic elite could concede on that single issue and take the rug from underneath organisers, who had seen the campaign in broader terms. Future campaigns should directly confront a taxation system which fails to alleviate rising wealth inequality. As we have seen, the top five percent in the country own over forty percent of its wealth, eighty-five per cent of which is held in property or land. A long-standing regime of minimal property taxes, along with the failure of the state to construct social housing to any extent, have severely accentuated wealth inequalities and seen property prices and rents spiral. A campaign for housing as an ‘inalienable and imprescriptible’ right enshrined in the constitution[xxx], should become the main progressive objective.

[i] ‘We Have Ways of Making You Think’, TV mini-series, BBC (1992)

[ii] David McWilliams, ‘Why do we tax income instead of wealth?’ http://www.davidmcwilliams.ie/why-do-we-tax-income-instead-of-wealth/, accessed 13/11/18.

[iii] Author unspecified, ‘Noonan: Budget 2016 the end of ‘boom and bust’’ Irish Examiner, October 13th, 2015.

[iv] Dan MacGuill, ‘FactCheck: How many social housing units were actually built last year?’, 9th of February, 2016, www.thejournal.ie, https://www.thejournal.ie/ge16-fact-check-election-2016-ireland-social-housing-2587923-Feb2016/, accessed 21/11/18.

[v] Lisa O’Carroll, ‘€43m knocked off Ireland’s most expensive house’ The Guardian, 22nd of September, 2011.

[vi] Fran Power, ‘Property prices in the Dublin market to hit boom-time levels ‘within the year’’, Irish Independent, September 3rd, 2017.

[vii] National Economic and Social Council, ‘Home Ownership and Rental: What Road is Ireland On?’ No. 140, December, 2014.

[viii] John Downing, ‘Ireland faces annual EU energy fines of €600m’ Irish Independent, April 30th, 2018.

[ix] Mark Hilliard, ‘Households pay most green taxes but emit one fifth of emissions – CSO’ Irish Times, October, 18th, 2018.

[x] Emma Dillon, Brian Moran, John Lennon and Trevor Donnellan, Teagasc National Farm Survey Results 2017, July 27th, 2018.

[xi] Cillian Sherlock, ‘790,000 people living in poverty in Ireland: Social Justice Ireland’, Irish Examiner, December 19th, 2017.

[xii] Carl O’Brien, ‘Teachers under pressure from ‘initiative overload’, says new Minister for Education’, Irish Times, October 18th, 2018.

[xiii] Numbeo, ‘Cost of Living in the UK’, https://www.numbeo.com/cost-of-living/country_result.jsp?country=United+Kingdom, accessed 13/11/18.

[xiv] Eoin Burke-Kennedy, Mark Hilliard, ‘Extent of State’s exposure to Brexit revealed by CSO figures’, Irish Times, October 18th, 2018.

[xv] National Adult Literacy Agency, ‘Literacy in Ireland’, https://www.nala.ie/literacy/literacy-in-ireland, accessed 13/11/18.

[xvi] Carl O’Brien, Jenna Clarke-Molloy, ‘Private school enrolment returns to boom-time high’, Irish Times, December 28th, 2017.

[xvii] David McCullagh, The Reluctant Taoiseach: A Biography of John A. Costello, Dublin, Gill and MacMillan, 2010, p.10.

[xviii] Tom Garvin ‘The bleak future of the Irish university’, Irish Times, May 1st, 2012.

[xix] The report summaries the payments made to the then Fine Gael Minister Michael Lowry saying, ‘In aggregating the known payments from Mr Denis O Brien to Mr Michael Lowry, it is apposite to note that, between the granting of the second GSM licence to Esat Digiphone in May 1996, and the transmission of £420,000 sterling to complete the purchase of the latter of Mr Lowry’s English properties in December 1999, Mr O’Brien had made or facilitated payments to Mr. Lowry of £147,000 sterling, £300,000 sterling and a benefit equivalent to a payment in the form of Mr O’Brien’s support for a loan of £420,000 sterling.’ From: Untitled, ‘Lowry helped O’Brien get mobile licence’, Untitled, RTÉ, 22nd of March, 2011, https://www.rte.ie/news/2011/0322/298935-moriarty_background/, accessed 16/11/18.

[xx] Social Justice Ireland, ‘Budget 2018 Analysis and Response Webinar’, https://www.socialjustice.ie/content/budget-2018-analysis-and-response-webinar, accessed 13/11/2018.

[xxi] Laurence Mackin, Conor Gallagher, ‘Seven women allege abuse and harassment by Michael Colgan’, Irish Times, November 4th, 2017.

[xxii] Kevin Doyle, ‘Varadkar orders review of Project Ireland €1.5m publicity campaign amid controversy’, Irish Independent, March 1st, 2018.

[xxiii] Rosita Boland, ‘Life on the Luas: a tale of two tracks’, Irish Times, October 14th, 2017.

[xxiv] Untitled, Stickybottle, ‘Flood of complaints to RTE after ‘Late Late Show’ cyclists item’ 14th of March, 2018, http://www.stickybottle.com/latest-news/complaints-rte-cyclists-item/

[xxv] Denise Deighan O’Callaghan, Letter to the Editor: ‘Tubridy’s comments on breastfeeding’, Irish Times, November 8th, 2004.

[xxvi] ‘Only one feature story over the two weeks carried an environmental angle, a story about new research into how dandelion seeds fly’ – ‘Gluaiseacht’, ‘Morning Ireland coverage: Sport 13 – Environment 1’ http://gluaiseacht.ie/content/morning-ireland-coverage-sport-13-environment-1, accessed 18/11/18.

[xxvii] David Hayden, ‘Shocking Climate Change denial aired on RTE during Claire Byrne Live’, Green News.ie, https://greennews.ie/shocking-climate-change-denial-aired-rte-claire-byrne-live/, accessed 13/11/18.

[xxviii] Sasha Brady, ‘Michael O’Leary slams climate change as ‘complete and utter rubbish’’, Irish Independent, April 8th, 2017.

[xxix] Theodore Zeldin, The Hidden Pleasures of Life: A New Way of Remembering the Past and Imagining the Future, London, Maclehouse Press, 2015. p.177.

[xxx] See Eoin Tierney, ‘The key Change to Fix the Irish Constitution’ July 1st, 2001, Cassandra Voices, http://cassandravoices.com/law/the-key-change-to-fix-the-irish-constitution/, accessed 21/11/18.